Klaus Mann

| Klaus Mann | |

|---|---|

|

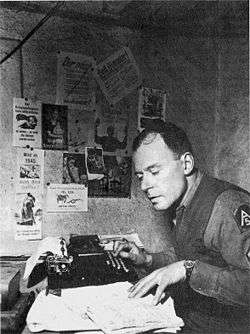

Klaus Mann, Staff Sergeant 5th US Army, Italy 1944 | |

| Born |

18 November 1906 Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire |

| Died |

21 May 1949 (aged 42) Cannes, France |

| Occupation |

Novelist Short story writer |

| Nationality | United States |

| Genre | Satire |

| Relatives |

Thomas Mann (father) Katia Pringsheim (mother) Erika Mann (sister) see full family tree |

Klaus Heinrich Thomas Mann (18 November 1906 – 21 May 1949) was a German writer.

Life and work

Born in Munich, Klaus Mann was the son of German writer Thomas Mann and his wife, Katia Pringsheim. His father was baptized as a Lutheran, while his mother was from a family of secular Jews. He began writing short stories in 1924 and the following year became drama critic for a Berlin newspaper. His first literary works were published in 1925.

Mann's early life was troubled. His homosexuality often made him the target of bigotry, and he had a difficult relationship with his father. After only a short time in various schools,[1] he travelled with his sister Erika Mann, a year older than himself, around the world, and visited the US in 1927.

In 1924 he had become engaged to his childhood friend Pamela Wedekind, the eldest daughter of the playwright Frank Wedekind, who was also a close friend of his sister Erika. The engagement was broken off in January 1928.

He travelled with Erika to North Africa in 1929. Around this time they made the acquaintance of Annemarie Schwarzenbach, a Swiss writer and photographer, who remained close to them for the next few years. Klaus made several trips abroad with Annemarie, the final one to a writers' congress in Moscow in 1934.[2]

In 1932 Klaus wrote the first part of his autobiography, which was well received until Hitler came to power.[3] In 1933 Klaus participated with Erika in a political cabaret, the Pepper-Mill, which came to the attention of the Nazi regime. To escape prosecution he left Germany in March 1933 for Paris, later visiting Amsterdam and Switzerland, where his family had a house.

In November 1934 Klaus was stripped of German citizenship by the Nazi regime. He became a Czechoslovak citizen. In 1936, he moved to the United States, living in Princeton, New Jersey, and New York. In the summer of 1937, he met his partner Thomas Quinn Curtiss, who was later a longtime film and theater reviewer for Variety and the International Herald Tribune. Mann became a US citizen in 1943.

During World War II, he served as a Staff Sergeant of the 5th US Army in Italy and in summer 1945 he was sent by the Stars and Stripes to report from Postwar-Germany.

Mann's most famous novel, Mephisto, was written in 1936 and first published in Amsterdam. The novel is a thinly-disguised portrait of his former brother-in-law, the actor Gustaf Gründgens. The literary scandal surrounding it made Mann posthumously famous in West Germany, as Gründgrens' adopted son brought a legal case to have the novel banned after its first publication in West Germany in the early 1960s. After seven years of legal hearings, the West German Supreme Court banned it by a vote of three to three, although it continued to be available in East Germany and abroad. The ban was lifted and the novel published in West Germany in 1981.

Mann's novel Der Vulkan is one of the 20th century's most famous novels about German exiles during World War II.

He died in Cannes of an overdose of sleeping pills on 21 May 1949, though whether he committed suicide is uncertain. He was buried there in the Cimetière du Grand Jas.

Select bibliography

- Der fromme Tanz, 1925

- Anja und Esther, 1925

- Revue zu Vieren, 1927

- Alexander, Roman der Utopie, 1929

- Kind dieser Zeit, 1932

- Treffpunkt im Unendlichen, 1932

- Journey into Freedom, 1934

- Symphonie Pathétique, 1935

- Mephisto, 1936

- Der Vulkan, 1939

- The Turning Point, 1942

- André Gide and the Crisis of Modern Thought, 1943

See also

References

Further reading

- Juliane Schicker. 'Decision. A Review of Free Culture' – Eine Zeitschrift zwischen Literatur und Tagespolitik. München: Grin, 2008. ISBN 978-3-638-87068-9

- James Robert Keller. The Role of Political and Sexual Identity in the Works of Klaus Mann. New York: Peter Lang, 2001. ISBN 0-8204-4906-7

- Hauck, Gerald Günter. Reluctant Immigrants: Klaus and Erika Mann In American Exile, 1936-1945. 1997.

- Huneke, Samuel Clowes. The Reception of Homosexuality in Klaus Mann's Weimar Era Work. Monatshefte für deutschsprachige Literatur und Kultur. Vol. 105, No. 1, Spring 2013. 86-100. doi: 10.1353/mon.2013.0027

- Mauthner, Martin German Writers in French Exile, 1933–1940 London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2006 ISBN 978-0853035404

- Spotts, Frederic. Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0300218008

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Klaus Mann |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Klaus Mann. |

- The Works, Diaries and Letters are in the Munich Literatur-Archiv "Monancensia"

- Tagebuch 1931–1949 – Titel – Mann Digital – Monacensia – Digital