Nibelungenlied

The Nibelungenlied, translated as The Song of the Nibelungs, is an epic poem in Middle High German. The story tells of dragon-slayer Siegfried at the court of the Burgundians, how he was murdered, and of his wife Kriemhild's revenge.

The Nibelungenlied is based on pre-Christian Germanic heroic motifs (the "Nibelungensaga"), which include oral traditions and reports based on historic events and individuals of the 5th and 6th centuries. Old Norse parallels of the legend survive in the Völsunga saga, the Prose Edda, the Poetic Edda, the Legend of Norna-Gest, and the Þiðrekssaga.

In 2009, the three main manuscripts of the Nibelungenlied were inscribed in UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in recognition of their historical significance.[1]

Manuscript sources

The poem in its various written forms was lost by the end of the 16th century, but manuscripts from as early as the 13th century were re-discovered during the 18th century. There are thirty-five known manuscripts of the Nibelungenlied and its variant versions. Eleven of these manuscripts are essentially complete.[2] The oldest version seems to be the one preserved in manuscript "B". Twenty-four manuscripts are in various fragmentary states of completion, including one version in Dutch (manuscript 'T'). The text contains approximately 2,400 stanzas in 39 Aventiuren. The title under which the poem has been known since its discovery is derived from the final line of one of the three main versions, "hie hât daz mære ein ende: daz ist der Nibelunge liet" ("here the story takes an end: this is the lay of the Nibelungs"). Liet here means lay, tale or epic rather than simply song, as it would in Modern German.

The manuscripts' sources deviate considerably from one another. Philologists and literary scholars usually designate three main genealogical groups for the entire range of available manuscripts, with two primary versions comprising the oldest known copies: *AB and *C. This categorization derives from the signatures on the *A, *B, and *C manuscripts as well as the wording of the last verse in each source: "daz ist der Nibelunge liet" or "daz ist der Nibelunge nôt". Nineteenth century philologist Karl Lachmann developed this categorisation of the manuscript sources in Der Nibelunge Noth und die Klage nach der ältesten Überlieferung mit Bezeichnung des Unechten und mit den Abweichungen der gemeinen Lesart (Berlin: Reimer, 1826).

Authorship

Prevailing scholarly theories strongly suggest that the written Nibelungenlied is the work of an anonymous poet from the area of the Danube between Passau and Vienna, dating from about 1180 to 1210, possibly at the court of Wolfger von Erla, the bishop of Passau (in office 1191–1204). Most scholars consider it likely that the author was a man of literary and ecclesiastical education at the bishop's court, and that the poem's recipients were the clerics and noblemen at the same court.

The "Nibelung's lament" (Diu Klage), a sort of appendix to the poem proper, mentions a "Meister Konrad" who was charged by a bishop "Pilgrim" of Passau with the copying of the text. This is taken as a reference to Saint Pilgrim, bishop of Passau from 971–991.

The search for the author of the Nibelungenlied in German studies has a long and intense history. Among the names suggested were Konrad von Fußesbrunnen, Bligger von Steinach and Walther von der Vogelweide. None of these hypotheses has wide acceptance, and mainstream scholarship today accepts that the author's name cannot be established.

Synopsis

Though the preface to the poem promises both joyous and dark tales ahead, the Nibelungenlied is by and large a very tragic work, and these four opening verses are believed to have been a late addition to the text, composed after the body of the poem had been completed.

| Middle High German original | Modern German | Shumway translation |

|---|---|---|

|

Uns ist in alten mæren wunders vil geseit |

Uns wird in alten Erzählungen viel Wunderbares berichtet, |

Full many a wonder is told us in stories old, |

The original version instead began with the introduction of Kriemhild, the protagonist of the work.

The epic is divided into two parts, the first dealing with the story of Siegfried and Kriemhild, the wooing of Brünhild and the death of Siegfried at the hands of Hagen, and Hagen's hiding of the Nibelung treasure in the Rhine (Chapters 1–19). The second part deals with Kriemhild's marriage to Etzel, her plans for revenge, the journey of the Burgundians to the court of Etzel, and their last stand in Etzel's hall (Chapters 20–39).

Siegfried and Kriemhild

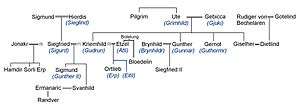

The first chapter introduces the court of Burgundy. Kriemhild (the virgin sister of King Gunther, and his brothers Gernot and Giselher) has a dream of a falcon that is killed by two eagles. Her mother interprets this to mean that Kriemhild's future husband will die a violent death, and Kriemhild consequently resolves to remain unmarried.

The second chapter tells of the background of Siegfried, crown prince of Xanten. His youth is narrated with little room for the adventures later attributed to him. In the third chapter, Siegfried arrives in Worms with the hopes of wooing Kriemhild. Upon his arrival, Hagen von Tronje, one of King Gunther's vassals, tells Gunther about Siegfried's youthful exploits that involved winning a treasure and lands from a pair of brothers, Nibelung and Schilbung, whom Siegfried had killed when he was unable to divide the treasure between them and, almost incidentally, the killing of a dragon. Siegfried leaves his treasure in the charge of a dwarf named Alberich.

After killing the dragon, Siegfried then bathed in its blood, which rendered him invulnerable. Unfortunately for Siegfried, a leaf fell onto his back from a linden tree, and the small patch of skin that the leaf covered did not come into contact with the dragon's blood, leaving Siegfried vulnerable in that single spot. In spite of Hagen's threatening stories about his youth, the Burgundians welcome him, but do not allow him to meet the princess. Disappointed, he nonetheless remains in Worms and helps Gunther defeat the invading Saxons.

In Chapter 5, Siegfried finally meets Kriemhild. Gunther requests Siegfried to sail with him to the fictional city of Isenstein in Iceland to win the hand of Iceland's Queen, Brünhild. Siegfried agrees, though only if Gunther allows him to marry Gunther's sister, Kriemhild, whom Siegfried pines for. Gunther, Siegfried and a group of Burgundians set sail for Iceland with Siegfried pretending to be Gunther's vassal. Upon their arrival, Brünhild challenges Gunther to a trial of strength with her hand in marriage as a reward. If they lose, however, they will be sentenced to death. She challenges Gunther to three athletic contests, throwing a javelin, tossing a boulder, and a leap. After seeing the boulder and javelin, it becomes apparent to the group that Brünhild is immensely strong and they fear for their lives.

Siegfried quietly returns to the boat on which his group had sailed and retrieves his special cloak, which renders him invisible and gives him the strength of 12 men (Chapters 6–8). Siegfried, with his immense strength, invisibly leads Gunther through the trials. Unknowingly deceived, the impressed Brünhild thinks King Gunther, not Siegfried, defeated her and agrees to marry Gunther. Gunther becomes afraid that Brünhild may yet be planning to kill them, so Siegfried goes to Nibelungenland and single-handedly conquers the kingdom. Siegfried makes them his vassals and returns with a thousand of them, himself going ahead as messenger. The group of Burgundians, Gunther and Gunther's new wife-to-be Brünhild return to Worms, where a grand reception awaits them and they marry to much fanfare. Siegfried and Kriemhild are also then married with Gunther's blessings.

However, on their wedding night, Brünhild suspects something is amiss with her situation, particularly suspecting Siegfried as a potential cause. Gunther attempts to sleep with her and, with her great strength, she easily ties him up and leaves him that way all night. After he tells Siegfried of this, Siegfried again offers his help, proposing that he slip into their chamber at night with his invisibility cloak and silently beat Brünhild into submission. Gunther agrees but says that Siegfried must not sleep with Brünhild. Siegfried slips into the room according to plan and after a difficult and violent struggle, an invisible Siegfried defeats Brünhild. Siegfried then takes her ring and belt, which are symbols of defloration. Here it is implied that Siegfried sleeps with Brünhild, despite Gunther's request. Afterwards, Brünhild no longer possesses her once-great strength and says she will no longer refuse Gunther. Siegfried gives the ring and belt to his own newly wed, Kriemhild, in Chapter 10.

Years later, Brünhild, still feeling as if she had been lied to, goads Gunther into inviting Siegfried and Kriemhild to their kingdom. Brünhild does this because she is still under the impression that Gunther married off his sister to a low-ranking vassal (while Gunther and Siegfried are in reality of equal rank) yet the normal procedures are not being followed between the two ranks combined with her lingering feelings of suspicion. Both Siegfried and Kriemhild come to Worms and all is friendly between the two until, before entering Worms Cathedral, Kriemhild and Brünhild argue over who should have precedence according to their husbands' perceived ranks.

Having been earlier deceived about the relationship between Siegfried and Gunther, Brünhild thinks it is obvious that she should go first, through custom of her perceived social rank. Kriemhild, unaware of the deception involved in Brünhild's wooing, insists that they are of equal rank and the dispute escalates. Severely angered, Kriemhild shows Brünhild first the ring and then the belt that Siegfried took from Brünhild on her wedding night, and then calls her Siegfried's kebse (mistress or concubine). Brünhild feels greatly distressed and humiliated, and bursts into tears.

The argument between the queens is both a risk for the marriage of Gunther and Brünhild and a potential cause for a lethal rivalry between Gunther and Siegfried, which both Gunther and Siegfried attempt to avoid. Gunther acquits Siegfried of the charges. Despite this, Hagen von Tronje decides to kill Siegfried to protect the honor and reign of his king. Although it is Hagen who does the deed, Gunther – who at first objects to the plot – along with his brothers knows of the plan and quietly assents. Hagen contrives a false military threat to Gunther, and Siegfried, considering Gunther a great friend, volunteers to help Gunther once again.

Under the pretext of this threat of war, Hagen persuades Kriemhild, who still trusts Hagen, to mark Siegfried's single vulnerable point on his clothing with a cross under the premise of protecting him. Now knowing Siegfried's weakness, the fake campaign is called off and Hagen then uses the cross as a target on a hunting trip, killing Siegfried with a javelin as he is drinking from a brook (Chapter 16). Kriemhild becomes aware of Hagen's deed when, in Hagen's presence, the corpse of Siegfried bleeds at the site of the wound (an old Norse legend held that the corpse of a murdered person would bleed in the presence of the murderer). This perfidious murder is particularly dishonorable in medieval thought, as throwing a javelin is the manner in which one might slaughter a wild beast, not a knight. We see this in other literature of the period, such as with Parsifal's unwittingly dishonorable crime of combatting and slaying knights with a javelin (transformed into a swan in Wagner's opera).[3] Further dishonoring Siegfried, Hagen steals the hoard from Kriemhild and throws it into the Rhine (Rheingold), to prevent Kriemhild from using it to establish an army of her own.[4]

Kriemhild's revenge

Kriemhild swears to take revenge for the murder of her husband and the theft of her treasure. Many years later, King Etzel of the Huns (Attila the Hun) proposes to Kriemhild, she journeys to the land of the Huns, and they are married. For the baptism of their son, she invites her brothers, the Burgundians, to a feast at Etzel's castle in Hungary. Hagen does not want to go, suspecting that it is a trick by Kriemhild in order to take revenge and kill them all, but is taunted until he does. As the Burgundians cross the Danube, this fate is confirmed by Nixes, who predict that all but one monk will die. Hagen tries to drown the monk in order to render the prophecy futile, but he survives.

The Burgundians arrive at Etzel's castle and are welcomed by Kriemhild "with lying smiles and graces." But the lord Dietrich of Bern, an ally of Etzel's, advises the Burgundians to keep their weapons with them at all times, which is normally not allowed. The tragedy unfolds as Kriemhild comes before Hagen, reproaching him for her husband Siegfried's death, and demands that he return her Nibelungenschatz. Hagen answers her boldly, admitting that he killed Siegfried and sank the Nibelungen treasure into the Rhine, but blames these acts on Kriemhild's own behavior.

King Etzel then welcomes his wife's brothers warmly. But outside a tense feast in the great hall, a fight breaks out between Huns and Burgundians, and soon there is general mayhem. When word of the fight arrives at the feast, Hagen decapitates the young son of Kriemhild and Etzel before their eyes. The Burgundians take control of the hall, which is besieged by Etzel's warriors. Kriemhild offers her brothers their lives if they hand over Hagen, but they refuse. The battle lasts all day, until the queen orders the hall to be burned with the Burgundians inside.

All of the Burgundians are killed except for Hagen and Gunther, who are bound and held prisoner by Dietrich of Bern. Kriemhild has the men brought before her and orders her brother Gunther to be killed. Even after seeing Gunther's head, Hagen refuses to tell the queen what he has done with the Nibelungen treasure. Furious, Kriemhild herself cuts off Hagen's head. Old Hildebrand, the mentor of Dietrich of Bern, is infuriated by the shameful deaths of the Burgundian guests. He hews Kriemhild to pieces with his sword. In a fifteenth-century manuscript, he is said to strike Kriemhild a single clean blow to the waist; she feels no pain, however, and declares that his sword is useless. Hildebrand then drops a ring and commands Kriemhild to pick it up. As she bends down, her body falls into pieces. Dietrich and Etzel and all the people of the court lament the deaths of so many heroes.

Historical background

The historical core of the saga is the defeat of the Burgundians by Flavius Aëtius with the aid of Hunnic mercenaries near Worms ca. AD 436. Other possible influences are the feud between the 6th century Merovingian queens Brunhilda and Fredegunde, as well as the marriage of Attila with the Burgundian princess Ildikó in AD 453, which took place the day before his death.

From the evidence of Waltharius, Nibelung is a name for the Franks, although there are other uses of the name in other medieval texts. The first part of the Nibelungenlied deals with Gunther's wooing of Brünhild and the murder of Siegfried, which takes place in Worms. The second part describes the journey of the Nibelungs east across the Danube to Etzelburg, the residence of Attila the Hun (Etzel), and the location of the final catastrophe. The Nibelungenlied arranges these traditional materials in a composition aiming at a High Medieval audience casting the inherited Germanic theme in a critical view of contemporary chivalry. Consequently, Siegfried changes from a dragon killer to a courtly man who will express his love to Kriemhild explicitly only after he has won the friendship of the Burgundian king Gunther and his brothers, Gernot and Giselher. Some situations, which exaggerate the conflict between the Germanic migrations and the chivalrous ethics (such as Gunther's embarrassing wedding night with Brünhild) may be interpreted as irony. The notoriously bloody end that leaves no hope for reconciliation is far removed from the happy ending of typical courtly epics, but is probably part of the original story. The bloody conclusion is also part of the overall critical dimension of the work.

Some scholars, particularly Delbrück, consider the historical figure of Arminius (Hermann), who defeated the Roman imperial legions (clad in scale armour) at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, a possible archetype for the dragon-slayer Siegfried.[5]

Legacy

An early critic labeled it a German Iliad, arguing that, like the Greek epic, it goes back to the remotest times and unites the monumental fragments of half-forgotten myths and historical personages into a poem that is essentially national in character.

Imagery from the Nibelungenlied was used in many poems, essays, posters and speeches at every stage in the development of German nationalism, from the Befreiungskriege (Wars of Liberation) to the regime of National Socialism (Nazism), to less jingoistic interpretations and references today.

For example, the faithfulness among the Burgundian king and his vassals, ranked higher than family bonds or life, is called Nibelungentreue. This expression was used in Germany, prior to World War I to describe the alliance between the German Empire and Austria-Hungary, as well as trying to inspire the army when referring to the Battle of Stalingrad.

The word Nibelungen is applied to the followers of Siegfried and finally to the Burgundians which are portrayed in the poem.

Today it is very difficult to separate the influence of the Nibelungenlied itself from that of other works of art and propaganda dealing with the Siegfried myths. Often, images which clearly refer to part of this story differ in some way. For example, one famous poster from the 1930s links Siegfried's death with the Dolchstosslegende (the idea that German soldiers were stabbed in the back by the peace treaties of 1918) and shows a Siegfried-like figure stabbed with a dagger, not a spear.

Adaptations

The Nibelungenlied, Thidreks saga and the Völsunga saga served as source materials for Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen (English: The Ring of the Nibelung), a series of four music dramas popularly known as the Ring Cycle.

In 1924, Austrian director Fritz Lang made a duology of silent fantasy films of the epic: Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhilds Rache. Lang and Thea von Harbou wrote the screenplay for the first film; von Harbou has the sole screenwriting credit on the second. Margarete Schön portrayed Kriemhild, Paul Richter portrayed Siegfried, and Hanna Ralph portrayed Brunhild. A two-part remake was made in 1966.

The premise of the Nibelungenlied was made into a miniseries called Ring of the Nibelungs (also called Sword of Xanten) in 2004. It adapts the title of the operatic series by Wagner and, like Der Ring des Nibelungen, is in many ways closer to the Norse legends of Sigurd and Brynhild than to the Nibelungenlied itself. Like many adaptations, it deals only with the first half of the epic, ignoring Kriemhild's revenge. On the SciFi Channel, it is broadcast with title Dark Kingdom: The Dragon King (2006).

Editions

- Karl Bartsch, Der Nibelunge Nôt : mit den Abweichungen von der Nibelunge Liet, den Lesarten sämmtlicher Handschriften und einem Wörterbuche, Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus, 1870–1880

- Michael S. Batts. Das Nibelungenlied, critical edition, Tübingen: M. Niemeyer 1971. ISBN 3-484-10149-0

- Helmut de Boor. Das Nibelungenlied, 22nd revised and expanded edition, ed. Roswitha Wisniewski, Wiesbaden 1988, ISBN 3-7653-0373-9. This edition is based ultimately on that of Bartsch.

- Hermann Reichert, Das Nibelungenlied, Berlin: de Gruyter 2005. VII, ISBN 3-11-018423-0. Edition of manuscript B, normalized text; introduction in German.

- Hermann Reichert, Nibelungenlied-Lehrwerk. Sprachlicher Kommentar, mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik, Wörterbuch. Passend zum Text der St. Galler Fassung („B“). Wien: Praesens Verlag 2007. ISBN 978-3-7069-0445-2. Linguistic help for beginners (in German).

- Ursula Schulze, Das Nibelungenlied, based on manuscript C, Düsseldorf / Zürich: Artemis & Winkler 2005. ISBN 3-538-06990-5.

Translations and adaptations

English

- Alice Horton, Translator. The Lay of the Nibelungs: Metrically Translated from the Old German Text, G. Bell and Sons, London, 1898. https://archive.org/stream/nibelungslay00hortrich Line by line translation of the "B manuscript". (Deemed the most accurate of the "older translations" in Encyclopedia of literary translation into English: M-Z, Volume 2, edited by Olive Classe, 2000, Taylor & Francis, pp. 999–1000.)

- Margaret Armour, Translator. Franz Schoenberner, Introduction. Edy Legrand, Illustrator. The Nibelungenlied, Heritage Press, New York, 1961

- A.T. Hatto, The Nibelungenlied, Penguin Classics 1964. English translation and extensive critical and historical appendices.

- Robert Lichtenstein. The Nibelungenlied, Translated and introduced by Robert Lichtenstein. (Studies in German Language and Literature Number: 9). Edwin Mellen Press, 1992. ISBN 0-7734-9470-7. ISBN 978-0-7734-9470-1.

- Burton Raffel, Das Nibelungenlied, new translation. Foreword by Michael Dirda. Introduction by Edward R. Haymes. Yale University Press 2006. ISBN 978-0-300-11320-4. ISBN 0-300-11320-X

- Michael Manning (Illustrator), Erwin Tschofen (Author), Michael Manning's The Nibelungen, sum legio publishing, 2010. ISBN 978-3-9502635-8-9.

- Cyril Edwards,The Nibelungenlied. The Lay of the Nibelungs, translated with an introduction and notes. Oxford University Press 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-923854-5.

Modern German

- Das Nibelungenlied. Zweisprachig, parallel text, edited and translated by Helmut de Boor. Sammlung Dieterich, 4th edition, Leipzig 1992, ISBN 3-7350-0104-1.

- Das Nibelungenlied. Mhd./Nhd., parallel text based on the edition of Karl Bartsch andHelmut de Boor, translated with commentary by Siegfried Grosse. Reclam Universal-Bibliothek. Band 644. Reclam, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-15-000644-9.

- Albrecht Behmel. Das Nibelungenlied, translation, Ibidem Verlag, 2nd edition, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 978-3-89821-145-1

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Song of the Nibelungs, a heroic poem from mediaeval Europe". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2009-07-31. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ the Donaueschingen manuscript C can be considered as the longest version, although some pages are missing

- ↑ This interpretation however is contradicted both by internal evidence in later parts of the Nibelungenlied, which describe knights casting spears at each other, and independently by evidence from mediaeval sources such as Talhoffer's illustrated "Fechtbuch" which clearly shows the casting of javelins s an element of knightly combat on foot, e.g. tafeln 70 & 71 of the 1467 edition.

- ↑ An alternative interpretation of Hagen's act is that he is just prudentially forestalling Kriemhild's anticipated revenge, which is of a piece with his overall stance of care to preserve the Burgundian dynasty.

- ↑ Delbrück, Hans. History of the Art of War, vol II. The Barbarian Invasions. Translated by Walter J. Renfroe. Bison Book, 1990. Pp. 120–121. ISBN 0-8032-9200-7.

References

- Müller, Jan-Dirk. Rules for the Endgame. The World of the Nibelungenlied. Translated by William T. Whobrey. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Pp. xv, 562.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nibelungenlied |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nibelungenlied. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Nibelungenlied. |

- Texts of manuscripts A, B and C

- Facsimile of manuscript C

- Karl Bartsch edition (Leipzig, 1870–80)

- Index of online manuscript facsimiles

- On-going audio recording in Middle High German

English translations

- Translation by Daniel B. Shumway

- Translation by Daniel B. Shumway

- Translation by Daniel B. Shumway

- The Nibelungenlied: Translated into Rhymed English Verse in the Metre of the Original by George Henry Needler

- The Lay of the Nibelungs – A line by line translation of the "B manuscript" by Alice Horton

-

The Nibelungenlied public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Nibelungenlied public domain audiobook at LibriVox