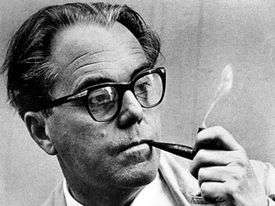

Max Frisch

| Max Frisch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Max Rudolf Frisch May 15, 1911 Zurich, Switzerland |

| Died |

April 4, 1991 (aged 79) Zurich, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Architect, novelist, playwright, philosopher |

| Language | German |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Spouse |

(married 1942, separated 1954, divorced 1959) Ingeborg Bachmann (partner 1958-1963) Marianne Oellers (married 1968, divorced 1979) |

Max Rudolf Frisch (May 15, 1911 – April 4, 1991) was a Swiss playwright and novelist. Frisch's works focused on problems of identity, individuality, responsibility, morality, and political commitment.[1] His use of irony is a significant feature of his post-war publications. Frisch was one of the founders of Gruppe Olten. He was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1986.

Biography

Early years

Frisch was born in 1911 in Zürich, the second son of Franz Bruno Frisch, an architect, and Karolina Bettina Frisch (née Wildermuth).[2] He had a half-sister, Emma (1899–1972), his father's daughter by a previous marriage, and a brother, Franz, eight years his senior (1903–1978). The family lived modestly, their financial situation deteriorating after the father lost his job during the First World War. Frisch had an emotionally distant relationship with his father, but was close to his mother. While at secondary school Frisch started to write drama, but failed to get his work performed and he subsequently destroyed his first literary works. While he was at school he met Werner Coninx (1911–1980), who later became a successful artist and collector. The two men formed a lifelong friendship.

In the 1930/31 academic year Frisch enrolled at the University of Zurich to study German literature and linguistics. There he met professors who gave him contact with the worlds of publishing and journalism. At this time, Frisch was influenced by Robert Faesi (1883–1972) and Theophil Spoerri (1890–1974), both writers and professors at the university. Frisch had hoped the university would provide him with the practical underpinnings for a career as a writer, but became convinced that university studies would not provide this.[3] In 1932, when financial pressure on the family intensified, Frisch abandoned his studies.

Journalism

Frisch made his first contribution to the newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) in May 1931, but the death of his father in March 1932 persuaded him to make a full-time career of journalism in order to generate an income to support his mother. He developed a lifelong ambivalent relationship with the NZZ; his later radicalism was in stark contrast to the conservative views of the newspaper. The move to the NZZ is the subject of his April 1932 essay, titled "Was bin ich?" ("What am I?"), his first serious piece of freelance work. Until 1934 Frisch combined journalistic work with coursework at the university.[4] Over 100 of his pieces survive from this period; they are autobiographical, rather than political, dealing with his own self-exploration and personal experiences, such as the break-up of his love affair with the 18-year-old actress Else Schebesta. Few of these early works made it into the published compilations of Frisch's writings that appeared after he had become better known. Frisch seems to have found many of them excessively introspective even at the time, and tried to distract himself by taking labouring jobs involving physical exertion, including a period in 1932 when he worked on road construction.

First novel

Between February and October 1933 he travelled extensively through eastern and southeastern Europe, financing his expeditions with reports written for newspapers and magazines. One of his first contributions was a report on the Prague World Ice Hockey Championship (1933) for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Other destinations were Budapest, Belgrade, Sarajevo, Dubrovnik, Zagreb, Istanbul, Athens, Bari, and Rome. Another product of this extensive tour was Frisch's first novel, Jürg Reinhart, which appeared in 1934. In it Reinhart represents the author, undertaking a trip though the Balkans as a way to find purpose in life. In the end the eponymous hero concludes that he can only become fully adult by performing a "manly act". This he achieves by helping the terminally ill daughter of his landlady end her life painlessly.

Käte Rubensohn and Germany

In the summer of 1934 Frisch met Käte Rubensohn,[5] who was three years his junior. The next year the two developed a romantic liaison. Rubensohn, who was Jewish, had emigrated from Berlin to continue her studies, which had been interrupted by government-led anti-Semitism and race-based legislation in Germany. In 1935 Frisch visited Germany for the first time. He kept a diary, later published as Kleines Tagebuch einer deutschen Reise (Short Diary of a German Trip), in which he described and criticised the antisemitism he encountered. At the same time, Frisch recorded his admiration for the Wunder des Lebens (Wonder of Life) exhibition staged by Herbert Bayer,[6] an admirer of the Hitler government's philosophy and policies. (Bayer was later forced to flee the country after annoying Hitler). Frisch failed to anticipate how Germany's National Socialism would evolve, and his early apolitical novels were published by the Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt (DVA) without encountering any difficulties from the German censors. During the 1940s Frisch developed a more critical political consciousness. His failure to become more critical sooner has been attributed in part to the conservative spirit at the University of Zurich, where several professors were openly sympathetic with Hitler and Mussolini.[7] Frisch was never tempted to embrace such sympathies, as he explained much later, because of his relationship with Käte Rubensohn,[8] even though the romance itself ended in 1939 after she refused to marry him.

The architect and his family

Frisch's second novel, An Answer from the Silence (Antwort aus der Stille), appeared in 1937. The book returned to the theme of a "manly act", but now placed it in the context of a middle class lifestyle. The author quickly became critical of the book, burning the original manuscript in 1937 and refusing to let it be included in a compilation of his works published in the 1970s. Frisch had the word "author" deleted from the "profession/occupation" field in his passport. Supported by a stipend from his friend Werner Coninx, he had in 1936 enrolled at the ETH Zurich (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule) to study architecture, his father's profession. His resolve to disown his second published novel was undermined when it won him the 1938 Conrad Ferdinand Meyer Prize, which included an award of 3,000 Swiss francs. At this time Frisch was living on an annual stipend from his friend of 4,000 francs.

With the outbreak of war in 1939, he joined the army as a gunner. Although Swiss neutrality meant that army membership was not a full-time occupation, the country mobilised to be ready to resist a German invasion, and by 1945 Frisch had clocked up 650 days of active service. He also returned to writing. 1939 saw the publication of From a Soldier's Diary (Aus dem Tagebuch eines Soldaten), which initially appeared in the monthly journal, Atlantis. In 1940 the same writings were compiled into the book Pages from the Bread-bag (Blätter aus dem Brotsack). The book was broadly uncritical of Swiss military life, and of Switzerland's position in war-time Europe, attitudes that Frisch revisited and revised in his 1974 Little Service Book (Dienstbuechlein); by 1974 he felt strongly that his country had been too ready to accommodate the interests of Nazi Germany during the war years.

At the ETH, Frisch studied architecture with William Dunkel, whose pupils also included Justus Dahinden and Alberto Camenzind, later stars of Swiss architecture. After receiving his diploma in the summer of 1940, Frisch accepted an offer of a permanent position in Dunkel's architecture office, and for the first time in his life was able to afford a home of his own. While working for Dunkel he met another architect, Gertrud Frisch-von Meyenburg, and on 30 July 1942 the two were married. The marriage produced three children: Ursula (1943), Hans Peter (1944), and Charlotte (1949). Much later, in a book of her own, Sturz durch alle Spiegel, which appeared in 2009,[9] his daughter Ursula reflected on her difficult relationship with her father.

In 1943 Frisch was selected from among 65 applicants to design the new Letzigraben (subsequently renamed Max-Frisch-Bad) swimming pool in the Zürich district of Albisrieden. Because of this substantial commission he was able to open his own architecture office, with a couple of employees. Wartime materials shortages meant that construction had to be deferred until 1947, but the public swimming pool was opened in 1949. It is now protected under historic monument legislation. In 2006/2007 it underwent an extensive renovation which returned it to its original condition.

Overall Frisch designed more than a dozen buildings, although only two were actually built. One was a house for his brother Franz and the other was a country house for the shampoo magnate, K.F. Ferster. Ferster's house triggered a major court action when it was alleged that Frisch had altered the dimensions of the main staircase without reference to his client. Frisch later retaliated by using Ferster as the model for the protagonist in his play The Fire Raisers (Biedermann und die Brandstifter).[10] When Frisch managed his own architecture office, he was generally found in his office only during the mornings. Much of his time and energy was devoted to writing.[11]

Theatre

Frisch was already a regular visitor at the Zürich Playhouse (Schauspielhaus) while still a student. Drama in Zürich was experiencing a golden age at this time, thanks to the flood of theatrical talent in exile from Germany and Austria. From 1944 the Playhouse director Kurt Hirschfeld encouraged Frisch to work for the theatre, and backed him when he did so. In Santa Cruz, his first play, written in 1944 and first performed in 1946, Frisch, who had himself been married since 1942, addressed the question of how the dreams and yearnings of the individual could be reconciled with married life. In his 1944 novel J'adore ce qui me brûle (I adore that which burns me) he had already placed emphasis on the incompatibility between the artistic life and respectable middle class existence. The novel reintroduces as its protagonist the artist Jürg Reinhart, familiar to readers of Frisch's first novel, and in many respects a representation of the author himself. It deals with a love affair that ends badly. This same tension is at the centre of a subsequent narrative by Frisch published, initially, by Atlantis in 1945 and titled Bin oder Die Reise nach Peking (Bin or the Journey to Beijing).

Both of his next two works for the theatre reflect the war. Now they sing again (Nun singen sie wieder), though written in 1945, was actually performed ahead of his first play Santa Cruz. It addresses the question of the personal guilt of soldiers who obey inhuman orders, and treats the matter in terms of the subjective perspectives of those involved. The piece, which avoids simplistic judgements, played to audiences not just in Zürich but also in German theatres during the 1946/47 season. The NZZ, then as now his native city's powerfully influential newspaper, pilloried the piece on its front page, claiming that it "embroidered" the horrors of National Socialism, and they refused to print Frisch's rebuttal. The Chinese Wall (Die Chinesieche Mauer) which appeared in 1946, explores the possibility that humanity might itself be eradicated by the (then recently invented) atomic bomb. The piece unleashed public discussion of the issues involved, and can today be compared with Friedrich Dürrenmatt's The Physicists (1962) and Heinar Kipphardt's On the J Robert Oppenheimer Affair (In der Sache J. Robert Oppenheimer), though these pieces are all now for the most part forgotten.

Working with the theatre director Hirschfeld enabled Frisch to meet some leading fellow playwrights who would influence his later work. He met the exiled German write, Carl Zuckmayer, in 1946, and the young Friedrich Dürrenmatt in 1947. Despite artistic differences on self-awareness issues, Dürrenmatt and Frisch became lifelong friends. 1947 was also the year in which Frisch met Bertolt Brecht, already established as a doyen of German theatre and of the political left. An admirer of Brecht's work, Frisch now embarked on regular exchanges with the older dramatist on matters of shared artistic interest. Brecht encouraged Frisch to write more plays, while placing emphasis on social responsibility in artistic work. Although Brecht's influence is evident in some of Frisch's theoretical views and can be seen in one or two of his more practical works, the Swiss writer could never have been numbered among Brecht's followers.[12] He kept his independent position, by now increasingly marked by scepticism in respect of the polarized political grandstanding which in Europe was a feature of the early cold war years. This is particularly apparent in his 1948 play As the war ended (Als der Krieg zu Ende war), based on eye-witness accounts of the Red Army as an occupying force.

Travels in post-war Europe

In April 1946 Frisch and Hirschfeld visited post-war Germany together.

In August 1948 Frisch visited Breslau/Wrocław to attend an International Peace Congress organized by Jerzy Borejsza. Breslau itself, which had been more than 90% German speaking as recently as 1945, was an instructive microcosm of the post-war settlement in central Europe. Poland's western frontier had moved, and the ethnically German majority in Breslau had escaped or been expelled from the city which now adopted its Polish name as Wrocław. The absented ethnic Germans were being replaced by relocated Polish speakers whose own formerly Polish homes were now included within the newly enlarged Soviet Union. A large number of European intellectuals were invited to the Peace Congress which was presented as part of a wider political reconciliation exercise between east and west. Frisch was not alone in quickly deciding that the congress hosts were simply using the event as an elaborate propaganda exercise, and there was hardly any opportunity for the "international participants" to discuss anything. Frisch left before the event ended and headed for Warsaw, notebook in hand, to collect and record his own impressions of what was happening. Nevertheless, when he returned home the resolutely conservative NZZ concluded that by visiting Poland Frisch had simply confirmed his status as a Communist sympathizer, and not for the first time refused to print his rebuttal of their simplistic conclusions. Frisch now served notice on his old newspaper that their collaboration was at an end.

Success as a novelist

By 1947 Frisch had accumulated roughly 130 filled notebooks, and these were published in a compilation titled Tagebuch mit Marion (Diary with Marion). In reality what appeared was not so much a diary as cross between a series of essays and literary autobiography. He was encouraged by the publisher Peter Suhrkamp to develop the format, and Suhrkamp provided his own feedback and specific suggestions for improvements. In 1950 Suhrkamp's own newly established publishing house produced a second volume of Frisch's Tagebuch covering the period 1946–1949, comprising a mosaic of travelogues, autobiographical musings, essays on political and literary theory and literary sketches, adumbrating many of the themes and sub-currents of his later fictional works. Critical reaction to the new impetus that Frisch's Tagebücher was giving to the genre of the "literary diary" was positive: there was a mention of Frisch having found a new way to connect with wider trends in European literature ("Anschluss ans europäische Niveau").[13] Sales of these works would nevertheless remain modest until the appearance of a new volume in 1958, by which time Frisch had become better known among the general book-buying public on account of his novels.

The Tagebuch 1946–1949 was followed, in 1951, by Count Öderland (Count Öderland), a play that picked up on a narrative that had already been sketched out in the "diaries". The story concerns a state prosecutor named Martin who grows bored with his middle-class existence, and drawing inspiration from the legend of Count Öderland, sets out in search of total freedom, using an axe to kill anyone who stands in his way. He ends up as the leader of a revolutionary freedom movement, and finds that the power and responsibility that his new position imposes on him leaves him with no more freedom than he had before. This play flopped, both with the critics and with audiences, and was widely misinterpreted as the criticism of an ideology or as being essentially nihilistic, and strongly critical of the direction that Switzerland's political consensus was by now following. Frisch nevertheless regarded Count Öderland as one of his most significant creations: he managed to get it returned to the stage in 1956 and again in 1961, but it failed, on both occasions, to win many new friends.

In 1951, Frisch was awarded a travel grant by the Rockefeller Foundation and between April 1951 and May 1952 he visited the United States and Mexico. During this time, under the working title "What do you do with love?" ("Was macht ihr mit der Liebe?") on what later became his novel, I'm Not Stiller (Stiller). Similar themes also underpinned the play Don Juan or the Love of Geometry (Don Juan oder Die Liebe zur Geometrie) which in May 1953 would open simultaneously at theatres in Zürich and Berlin. In this play Frisch returned to his theme of the conflict between conjugal obligations and intellectual interests. The leading character is a parody Don Juan, whose priorities involve studying geometry and playing chess, while women are let into his life only periodically. After his unfeeling conduct has led to numerous deaths the anti-hero finds himself falling in love with a former prostitute. The play proved popular and has been performed more than a thousand times, making it Frisch's third most popular drama after The Fire Raisers (1953) and Andorra (1961).

The novel I'm Not Stiller appeared in 1954. The protagonist, Anatol Ludwig Stiller starts out by pretending to be someone else, but in the course of a court hearing he is forced to acknowledge his original identity as a Swiss sculptor. For the rest of his life he returns to live with the wife whom, in his earlier life, he had abandoned. The novel combines elements of crime fiction with an authentic and direct diary-like narrative style. It was a commercial success, and won for Frisch widespread recognition as a novelist. Critics praised its carefully crafted structure and perspectives, as well as the way it managed to combine philosophical insight with autobiographical elements. The theme of the incompatibility between art and family responsibilities is again on display. Following the appearance of this book Frisch, whose own family life had been marked by a succession of extra-marital affairs,[14] left his family, moving to Männedorf, where he had his own small apartment in a farmhouse. By this time writing had become his principal source of income, and in January 1955 he closed his architectural practice, becoming officially a full-time freelance writer.

At the end of 1955 Frisch started work on his novel, Homo Faber which would be published in 1957. It concerns an engineer who views life through a "technical" ultra-rational prism. Homo Faber was chosen as a study text for the schools and became the most read of Frisch's books. The book involves a journey which mirrors a trips that Frisch himself undertook to Italy in 1956, and later across the Atlantic for a second visit to America, this time also taking in both Mexico and Cuba. The following year Frisch visited Greece which is where the latter part of Homo Faber unfolds.

Success (and some disappointments) as a dramatist

The success of The Fire Raisers established Frisch as a world-class dramatist. It deals with a lower middle-class man who is in the habit of giving shelter to vagrants who, despite clear warning signs to which he fails to react, burn down his house. Early sketches for the piece had been produced, in the wake of the communist take-over in Czechoslovakia, back in 1948, and had been published in his Tagebuch 1946–1949. A radio play based on the text had been transmitted in 1953 on Bavarian Radio (BR). Frisch's intention with the play was to shake the self-confidence of the audience that, faced with equivalent dangers, they would necessarily react with the necessary prudence. Swiss audiences simply understood the play as a warning against Communism, and the author felt correspondingly misunderstood. For the subsequent premier in West Germany he added a little sequel which was intended as a warning against Nazism, though this was later removed.

A sketch for Frisch's next play, Andorra had also already appeared in the Tagebuch 1946–1949. Andorra deals with the power of preconceptions concerning fellow human beings. The principal character, Andri, is a youth who is assumed to be, like his father, Jewish. The boy therefore has to deal with anti-semitic prejudice, and while growing up he has acquired traits which those around him regard as "typically Jewish". There is also exploration of various associated individual hypocrisies that arise in the small fictional town where the action takes place. It later transpires that Andri is his father's adopted son and therefore not himself Jewish, although the townsfolk are too focused on their preconceptions to accept this. The themes of the play seem to have been particularly close to the author's heart: in the space of three years Frisch had written no fewer than five versions before, towards the end of 1961, it received its first performance. The play was a success both with the critics and commercially. It nevertheless attracted controversy, especially after it opened in the United States, from those who thought that it treated with unnecessary frivolity issues which were still extremely painful so soon after the Nazi Holocaust had been publicised in the west. Another criticism was that by presenting its theme as one of generalised human failings, the play somehow diminished the level of specifically German guilt for recent real-life atrocities.

During July 1958 Frisch got to know the Carinthian writer Ingeborg Bachmann, and the two became lovers. He had left his wife and children in 1954 and now, in 1959, he was divorced. Although Bachmann rejected the idea of a formal marriage, Frisch nevertheless followed her to Rome where by now she lived, and the city became the centre of both their lives until (in Frisch's case) 1965. The relationship between Frisch and Bachmann was intense, but not free of tensions. Frisch remained true to his habit of sexual infidelity, but reacted with intense jealousy when his partner demanded the right to behave in much the same way.[15] His 1964 novel Gantenbein / A Wilderness of Mirrors (Mein Name sei Gantenbein) – and indeed Bachmann's later novel, Malina – both reflect the writers' reactions to this relationship which broke down during the bitterly cold winter of 1962/63 when the lovers were staying in Uetikon. Gantenbein works through the ending of a marriage with a complicated succession of "what if?" scenarios: the identities and biographical background of the parties get switched along with details of their shared married life. The writer tests alternative narratives "like clothes", and comes to the conclusion that none of the tested scenarios leads to an entirely "fair" outcome. Frisch himself wrote of Gantenbein that his purpose was "to show the reality of an individual by having him appear as a blank patch outlined by the sum of fictional entities congruent with his personality. ... The story is not told as if an individual could be identified by his factual behaviour; let him betray himself in his fictions."[16]

His next play Biography: A game (Biografie: Ein Spiel), followed on naturally. Frisch was disappointed that his commercially very successful plays Biedermann und die Brandstifter and Andorra had both been, in his view, widely misunderstood. His answer was to move away from the play as a form of parable, in favour of a new form of expression which he termed "Dramaturgy of Permutation" ("Dramaturgie der Permutation"), a form which he had introduced with Gantenbein and which he now progressed with Biographie, written in its original version in 1967. At the centre of the play is a behavioural scientist who is given the chance to live his life again, and finds himself unable to take any key decisions differently the second time round. The Swiss premier of the play was to have been directed by Rudolf Noelte, but Frisch and Noelte fell out in the Autumn of 1967, a week before the scheduled first performance, which led to the Zürich opening being postponed for several months. In the end the play opened in the Zürich Playhouse in February 1968, the performances being directed by Leopold Lindtberg. Lindtberg was a long established and well regarded theatre director, but his production of Biografie: Ein Spiel neither impressed the critics nor delighted theatre audiences. Frisch ended up deciding that he had been expecting more from the audience than he should have expected them to bring to the theatrical experience. After this latest disappointment it would be another eleven years before Frisch returned to theatrical writing.

Second marriage to Marianne Oellers and a growing propensity to avoid Switzerland

In Summer 1962 Frisch met Marianne Oellers, a student of Germanistic and Romance studies. He was 51 and she was 28 years younger. In 1964 they moved into an apartment together in Rome, and in the Autumn of 1965 they relocated to Switzerland, setting up home together in an extensively modernised cottage in Berzona, Ticino.[17] During the next decade much of their time was spent living in rented apartments abroad, and Frisch could be scathing about his Swiss homeland, but they retained their Berzona property and frequently returned to it, the author driving his Jaguar from the airport: as he himself was quoted at the time on his Ticino retreat, "Seven times a year we drive this stretch of road ... This is fantastic countryside"[17][18] As a "social experiment" they also, in 1966, temporarily occupied a second home in an apartment block in Aussersihl, a residential quarter of down-town Zürich known, then as now, for its high levels of recorded crime and delinquency, but they quickly swapped this for an apartment in Küsnacht, close to the lake shore. Frisch and Oellers were married at the end of 1968.

Marianne Oellers accompanied her future husband on numerous foreign trips. In 1963 they visited the United States for the American premieres of The Fire Raisers and Andorra, and in 1965 they visited Jerusalem where Frisch was presented with the Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in Society. In order to try and form an independent assessment of "Life behind the Iron Curtain" they then, in 1966, toured the Soviet Union. They returned two years later to attend a "Writers' Congress" at which they met Christa and Gerhard Wolf, leading authors in what was then East Germany, with whom they established lasting friendships. After they married, Frisch and his young wife continued to travel extensively, visiting Japan in 1969 and undertaking extended stays in the United States. Many impressions of these visits are published in Frisch's Tagebuch covering the period 1966–1971.

In 1972, after returning from the US, the couple took a second apartment in the Friedenau quarter of West Berlin, and this soon became the place where they spent most of their time. During the period 1973–79 Frisch was able to participate increasingly in the intellectual life of the place. Living away from his homeland intensified his negative attitude to Switzerland, which had already been apparent in William Tell for Schools (Wilhelm Tell für die Schule) (1970) and which reappears in his Little service book (Dienstbüchlein) (1974), in which he reflects on his time in the Swiss army some 30 years earlier. More negativity about Switzerland was on show in January 1974 when he delivered a speech titled "Switzerland as a homeland?" ("Die Schweiz als Heimat?"), when accepting the 1973 Grand Schiller Prize from the Swiss Schiller Foundation. Although he nurtured no political ambitions on his own account, Frisch became increasingly attracted to the ideas of social democratic politics. He also became friendly with Helmut Schmidt who had recently succeeded the Berlin–born Willy Brandt as Federal Chancellor of West Germany and was already becaming something of a respected elder statesman for the country's moderate left (and, as a former Defence Minister, a target of opprobrium for some on the SPD's immoderate left). In October 1975, slightly improbably, the Swiss dramatist Frisch accompanied Chancellor Schmidt on what for them both was their first visit to China,[19] as part of an official West German delegation. Two years later, in 1977, Frisch found himself accepting an invitation to give a speech at an SPD Party Conference.

In April 1974, while on a book tour in the USA, Frisch launched into an affair with an American called Alice Locke-Carey who was 32 years his junior. This happened in the village of Montauk on Long Island, and Montauk was the title the author gave to an autobiographical novel that appeared in 1975. The book centred on his love life, including both his own marriage with Marianne Oellers-Frisch and an affair that she had been having with the American writer Donald Barthelme. There followed a very public dispute between Frisch and his wife over where to draw the line between private and public life, and the two because increasingly estranged, divorcing in 1979.

Later works, old age and death

In 1978, Frisch survived serious health problems, and the next year was actively involved in setting up the Max Frisch Foundation (Max-Frisch-Stiftung), established in October 1979, and to which he entrusted the administration of his estate. The foundation's archive is kept at the ETH Zurich, and has been publicly accessible since 1983.

Old age and the transience of life now came increasingly to the fore in Frisch's work. In 1976 he began work on the play Triptychon, although it was not ready to be performed for another three years. The word triptych is more usually applied to paintings, and the play is set in three triptych-like sections in which many of the key characters are notionally dead. The piece was first unveiled as a radio play in April 1979, receiving its stage premier in Lausanne six months later. The play was rejected for performance in Frankfurt am Main where it was deemed too apolitical. The Austrian premier in Vienna at the Burgtheater was seen by Frisch as a success, although the audience reaction to the complexity of the work's unconventional structure was still a little cautious.

In 1980, Frisch resumed contact with Alice Locke-Carey and the two of them lived together, alternately in New York City and in Frisch's cottage in Berzona, till 1984. By now Frisch had become a respected and from time to time honoured writer in the United States. He received an honorary doctorate from Bard College in 1980 and another from New York's City University in 1982. An English translation of the novella Man in the Holocene (Der Mensch erscheint im Holozän) was published by The New Yorker in May 1980, and was picked out by critics in The New York Times Book Review as the most important and most interesting published narrative work of 1980. The story concerns a retired industrialist suffering from the decline in his mental faculties and the loss of the camaraderie which he used to enjoy with colleagues. Frisch was able, from his own experience of approaching old age, to bring a compelling authenticity to the piece, although he rejected attempts to play up its autobiographical aspects. After Man in the Holocene appeared in 1979 (in the German language edition) the author developed writers' block, which ended only with the appearance, in the Autumn/Fall of 1981 of his final substantial literary piece, the prose text/novella Bluebeard (Blaubart).

In 1984 Frisch returned to Zürich, where he would live for the rest of his life. In 1983 he began a relationship with his final life partner, Karen Pilliod.[20] She was only 25 younger than he was.[20] In 1987 they visited Moscow and together took part in the "Forum for a world liberated from atomic weapons". After Frisch's death Pilliod let it be known that between 1952 and 1958 Frisch had also had an affair with her mother, Madeleine Seigner-Besson.[20] In March 1989 he was diagnosed with incurable colorectal cancer. In the same year, in the context of the Swiss Secret files scandal, it was discovered that the national security services had been illegally spying on Frisch (as on many other Swiss citizens) ever since he had attended the International Peace Congress at Wrocław/Breslau in 1948.

Frisch now arranged his funeral, but he also took time to engage in discussion about the abolition of the army, and published a piece in the form of a dialogue on the subject titled Switzerland without an Army? A Palaver (Schweiz ohne Armee? Ein Palaver) There was also a stage version titled Jonas and his veteran (Jonas und sein Veteran). Frisch died on 4 April 1991 while in the middle of preparing for his 80th birthday. The funeral, which Frisch had planned with some care,[21] took place on 9 April 1991 at St Peter's Church in Zürich. His friends Peter Bichsel and Michel Seigner spoke at the ceremony. Karin Pilliod also read a short address, but there was no speech from any church minister. Frisch was an agnostic who found religious beliefs superfluous.[22] His ashes were later scattered on a fire by his friends at a memorial celebration back in Ticino at a celebration of his friends. A tablet on the wall of the cemetery at Berzona commemorates him.

Literary output

Genres

The diary as a literary form

The diary became a very characteristic prose form for Frisch. In this context, diary does not indicate a private record, made public to provide readers with voyeuristic gratification, nor an intimate journal of the kind associated with Henri-Frédéric Amiel. The diaries published by Frisch were closer to the literary "structured consciousness" narratives associated with Joyce and Döblin, providing an acceptable alternative but effective method for Frisch to communicate real-world truths.[23] After he had intended to abandon writing, pressured by what he saw as an existential threat from his having entered military service, Frisch started to write a diary which would be published in 1940 with the title "Pages from the Bread-bag" ("Blätter aus dem Brotsack"). Unlike his earlier works, output in diary form could more directly reflect the author's own positions. In this respect the work influenced Frisch's own future prose works. He published two further literary diaries covering the periods 1946–1949 and 1966–1971. The typescript for a further diary, started in 1982, was discovered only in 2009 among the papers of Frisch's secretary.[24] Before that it had been generally assumed that Frisch had destroyed this work because he felt that the decline of his creativity and short term memory meant that he could no longer do justice to the diary genre.[25] The newly discovered typescript was published in March 2010 by Suhrkamp Verlag. Because of its rather fragmentary nature Frisch's Diary 3 (Tagebuch 3) was described by the publisher as a draft work by Frisch: it was edited and provided with an extensive commentary by Peter von Matt, chairman of the Max Frisch Foundation.[24]

Many of Frisch's most important plays, such as Count Öderland (Count Öderland) (1951), Don Juan or the Love of Geometry (Don Juan oder Die Liebe zur Geometrie) (1953), The Fire Raisers (1953) and Andorra (1961), were initially sketched out in the Diary 1946–1949 (Tagebuch 1946–1949) some years before they appeared as stage plays. At the same time several of his novels such as I'm Not Stiller (1954), Homo Faber (1957) as well as the narrative work Montauk (1975) take the form of diaries created by their respective protagonists. Sybille Heidenreich points out that even the more open narrative form employed in Gantenbein / A Wilderness of Mirrors (1964) closely follows the diary format.[26] Rolf Keiser points out that when Frisch was involved in the publication of his collected works in 1976, the author was keen to ensure that they were sequenced chronologically and not grouped according to genre: in this way the sequencing of the collected works faithfully reflects the chronological nature of a diary.[27]

Frisch himself took the view that the diary offered the prose format that corresponded with his natural approach to prose writing, something that he could "no more change than the shape of his nose".[26] Attempts were nevertheless made by others to justify Frisch's choice of prose format. Frisch's friend and fellow-writer, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, explained that in I'm Not Stiller the "diary-narrative" approach enabled the author to participate as a character in his own novel without embarrassment.[28] (The play focuses on the question of identity, which is a recurring theme in the work of Frisch.) More specifically, in the character of James Larkin White, the American who in reality is indistinguishable from Stiller himself, but who nevertheless vigorously denies being the same man, embodies the author, who in his work cannot fail to identify the character as himself, but is nevertheless required by the literary requirements of the narrative to conceal the fact. Rolf Keiser points out that the diary format enables Frisch most forcefully to demonstrate his familiar theme that thoughts are always based on one specific standpoint and its context; and that it can never be possible to present a comprehensive view of the world, nor even to define a single life, using language alone.[27]

Narrative form

Frisch's first public success was as a writer for theatre, and later in his life he himself often stressed that he was in the first place a creature of the theatre. Nevertheless, the diaries, and even more than these, the novels and the longer narrative works are among his most important literary creations. In his final decades Frisch tended to move away from drama and concentrate on prose narratives. He himself is on record with the opinion that the subjective requirements of story telling suited him better than the greater level of objectivity required by theatre work.[29]

In terms of the timeline, Frisch's prose works divide roughly into three periods.

His first literary works, up till 1943, all employed prose formats. There were numerous short sketches and essays along with three novels or longer narratives, Jürg Reinhart (1934), it's belated sequel J'adore ce qui me brûle (I adore that which burns me) (1944) and the narrative An Answer from the Silence (Antwort aus der Stille) (1937). All three of the substantive works are autobiographical and all three centre round the dilemma of a young author torn between bourgeois respectability and "artistic" life style, exhibiting on behalf of the protagonists differing outcomes to what Frisch saw as his own dilemma.

The high period of Frisch's career as an author of prose works is represented by the three novels I'm Not Stiller (1954), Homo Faber (1957) and Gantenbein / A Wilderness of Mirrors (1964), of which Stiller is generally regarded as his most important and most complex book, according to the US based German scholar Alexander Stephan, in terms both of its structure and its content.[30] What all three of these novels share is their focus on the identity of the individual and on the relationship between the sexes. In this respect Homo Faber and Stiller offer complementary situations. If Stiller had rejected the stipulations set out by others, he would have arrived at the position of Walter Faber, the ultra-rationalist protagonist of Homo Faber.[31] Gantenbein / A Wilderness of Mirrors (Mein Name sei Gantenbein) offers a third variation on the same theme, apparent already in its (German language) title. Instead of baldly asserting "I am not (Stiller)" the full title of Gantebein uses the German "Conjunctive" (subjunctive) to give a title along the lines "My name represents (Gantenbein)". The protagonist's aspiration has moved on from the search for a fixed identity to a less binary approach, trying to find a midpoint identity, testing out biographical and historic scenarios.[30]

Again, the three later prose works Montauk (1975), Man in the Holocene (Der Mensch erscheint im Holozän) (1979), and Bluebeard (Blaubart) (1981), are frequently grouped together by scholars. All three are characterized by a turning towards death and a weighing up of life. Structurally they display a savage pruning of narrative complexity. The Hamburg born critic Volker Hage identified in the three works "an underlying unity, not in the sense of a conventional trilogy ... but in the sense that they together form a single literary chord. The three books complement one another while each retains its individual wholeness ... All three books have a flavour of the balance sheet in a set of year-end financial accounts, disclosing only that which is necessary: summarized and zipped up".[32][33] Frisch himself produced a more succinct "author's judgement": "The last three narratives have just one thing in common: they allow me to experiment with presentational approaches that go further than the earlier works." [34]

Dramas

Frisch's dramas up until the early 1960s are divided by the literary commentator Manfred Jurgensen into three groups: (1) the early wartime pieces, (2) the poetical plays such as Don Juan or the Love of Geometry (Don Juan oder Die Liebe zur Geometrie) and (3) the dialectical pieces.[35] It is above all with this third group, notably the parable The Fire Raisers (1953), identified by Frisch as a "lesson without teaching", and with Andorra (1961) that Frisch enjoyed the most success. Indeed, these two are among the most successful German language plays.[36] The writer nevertheless remained dissatisfied because he believed they had been widely misunderstood. In an interview with Heinz Ludwig Arnold Frisch vigorously rejected their allegorical approach: "I have established only that when I apply the parable format, I am obliged to deliver a message that I actually do not have".[37][38] After the 1960s Frisch moved away from the theatre. His late biographical plays Biography: A game (Biografie: Ein Spiel) and Triptychon were apolitical but they failed to match the public success of his earlier dramas. It was only shortly before his death that Frisch returned to the stage with a more political message, with Jonas and his Veteran, a stage version of his arresting dialogue Switzerland without an army? A Palaver.

For Klaus Müller-Salget, the defining feature which most of Frisch's stage works share is their failure to present realistic situations. Instead they are mind games that toy with time and space. For instance, The Chinese Wall (Die Chinesieche Mauer) (1946) mixes literary and historical characters, while in the Triptychon we are invited to listen to the conversations of various dead people. In Biography: A game (Biografie: Ein Spiel) a life-story is retrospectively "corrected", while Santa Cruz and Prince Öderland (Graf Öderland) combine aspects of a dream sequence with the features of a morality tale. Characteristic of Frisch's stage plays are minimalist stage-sets and the application of devices such as splitting the stage in two parts, use of a "Greek chorus" and characters addressing the audience directly. In a manner reminiscent of Brecht's epic theatre, audience members are not expected to identify with the characters on stage, but rather to have their own thoughts and assumptions stimulated and provoked. Unlike Brecht however, Frisch offered few insights or answers, preferring to leave the audience the freedom to provide their own interpretations.[39]

Frisch himself acknowledged that the part of writing a new play that most fascinated him was the first draft, when the piece was undefined, and the possibilities for its development were still wide open. The critic Hellmuth Karasek identified in Frisch's plays a mistrust of dramatic structure, apparent from the way in which Don Juan or the Love of Geometry applies theatrical method. Frisch prioritized the unbelievable aspects of theatre and valued transparency. Unlike his friend, the dramatist Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Frisch had little appetite for theatrical effects, which might distract from doubts and sceptical insights included in a script. For Frisch, effects came from a character being lost for words, from a moment of silence, or from a misunderstanding. And where a Dürrenmatt drama might lead, with ghastly inevitability, to a worst possible outcome, the dénouement in a Frisch play typically involved a return to the starting position: the destiny that awaited his protagonist might be to have no destiny.[40]

Style and language

Frisch's style changed across the various phases of his work.

His early work is strongly influenced by the poetical imagery of Albin Zollinger, and not without a certain imitative lyricism, something from which in later life he would distance himself, dismissing it as "phoney poeticising" ("falscher Poetisierung"). His later works employed a tighter, consciously unpretentious style, which Frisch himself described as "generally very colloquial" ("im Allgemeinen sehr gesprochen."). Walter Schenker saw Frisch's first language as Zurich German, the dialect of Swiss German with which he grew up. The Standard German to which he was introduced as a written and literary language is naturally preferred for his written work, but not without regular appearances by dialect variations, introduced as a stylistic devices.[41]

A defining element in Frisch was an underlying scepticism as to the adequacy of language. In I'm Not Stiller his protagonist cries out, "I have no language for my reality!" ("... ich habe keine Sprache für meine Wirklichkeit!").[42] The author went further in his Diary 1946–49 (Tagebuch 1946–49): "What is important: the unsayable, the white space between the words, while these words themselves we always insert as side-issues, which as such are not the central part of what we mean. Our core concern remains unwritten, and that means, quite literally, that you write around it. You adjust the settings. You provide statements that can never contain actual experience: experience itself remains beyond the reach of language.... and that unsayable reality appears, at best, as a tension between the statements."[43] Werner Stauffacher saw in Frisch's language "a language the searches for humanity's unspeakable reality, the language of visualisation and exploration", but one that never actually uncovers the underlying secret of reality.[44]

Frisch adapted principals of Bertolt Brecht's Epic theatre both for his dramas and for his prose works. As early as 1948 he concluded a contemplative piece on the alienation effect with the observation, "One might be tempted to ascribe all these thoughts to the narrative author: the linguistic application of the alienation effect, the wilfully mischievous aspect of the prose, the uninhibited artistry which most German language readers will reject because they find it "too arty" and because it inhibits empathy and connection, sabotaging the conventional illusion that the story in the narrative really happened."[45][46] Notably, in the 1964 novel " Gantenbein" ("A Wilderness of Mirrors"), Frisch rejected the conventional narrative continuum, presenting instead, within a single novel, a small palette of variations and possibilities. The play "Biography: A game" ("Biografie: Ein Spiel") (1967) extended similar techniques to theatre audiences. Already in " Stiller" (1954) Frisch embedded, in a novel, little sub-narratives in the form of fragmentary episodic sections from his "diaries".[47] In his later works Frisch went further with a form of montage technique that produced a literary collage of texts, notes and visual imagery in "The Holozän" (1979).[48]

Themes and motifs

Frisch's literary work centre round certain core themes and motifs many of which, in various forms, recur through the entire range of the author's output.

Image vs. identity

In the Diary 1946–1949 Frisch spells out a central idea that runs through his subsequent work: "You shall not make for yourself any graven image, God instructs us. That should also apply in this sense: God lives in every person, though we may not notice. That oversight is a sin that we commit and it is a sin that is almost ceaselessly committed against us – except if we love".[49][50] The biblical instruction is here taken to be applied to the relationship between people. It is only through love that people may manifest the mutability and versatility necessary to accept one another's intrinsic inner potential. Without love people reduce one another and the entire world down to a series of simple preformed images. Such a cliché based image constitutes a sin against the self and against the other.

Hans Jürg Lüthi divides Frisch's work, into two categories according to how this image is treated. In the first category, the destiny of the protagonist is to live the simplistic image. Examples include the play Andorra (1961) in which Andri, identified (wrongly) by the other characters as a Jew is obliged to work through the fate assigned to him by others. Something analogous arises with the novel Homo Faber (1957) where the protagonist is effectively imprisoned by the technician's "ultra-rational" prism through which he is fated to conduct his existence. The second category of works identified by Lüthi centres on the theme of libration from the lovelessly predetermined image. In this second category he places the novels I'm Not Stiller (1954) and Gantenbein (1964), in which the leading protagonists create new identities precisely in order to cast aside their preformed cliché-selves.[51]

Real personal identity stands in stark contrast to this simplistic image. For Frisch, each person possesses a unique Individualism, justified from the inner being, and which needs to be expressed and realized. To be effective it can operate only through the individual's life, or else the individual self will be incomplete.[52][53] The process of self acceptance and the subsequent self-actualization constitute a liberating act of choice: "The differentiating human worth of a person, it seems to me, is Choice".[54][55] The "selection of self" involves not a one-time action, but a continuing truth that the "real myself" must repeatedly recognize and activate, behind the simplistic images. The fear that the individual "myself" may be overlooked and the life thereby missed, was already a central theme in Frisch's early works. A failure in the "selection of self" was likely to result in alienation of the self both from itself and from the human world more generally. Only within the limited span of an individual human life can personal existence find a fulfilment that can exclude the individual from the endless immutability of death. In I'm Not Stiller Frisch set out a criterion for a fulfilled life as being "that an individual be identical with himself. Otherwise he has never really existed".[56]

Relationships between the sexes

Claus Reschke says that the male protagonists In Frisch's work are all similar modern intellectual types: egocentric, indecisive, uncertain in respect of their own self-image, they often misjudge their actual situation. Their interpersonal relationships are superficial to the point of agnosticism, which condemns them to live as isolated loners. If they do develop some deeper relationship involving women, they lose emotional balance, becoming unreliable partners, possessive and jealous. They repeatedly assume outdated gender roles, masking sexual insecurity behind chauvinism. All this time their relationships involving women are overshadowed by feelings of guilt. In a relationship with a woman they look for "real life", from which they can obtain completeness and self-fulfilment, untrammelled by conflict and paralyzing repetition, and which will never lose elements of novelty and spontaneity.[57]

Female protagonists in Frisch's work also lead back to a recurring gender-based stereotype, according to Mona Knapp. Frisch's compositions tend to be centred on male protagonists, around which his leading female characters, virtually interchangeable, fulfil a structural and focused function. Often they are idolised as "great" and "wonderful", superficially emancipated and stronger than the men. However, they actually tend to be driven by petty motivations: disloyalty, greed and unfeelingness. In the author's later works the female characters become increasingly one-dimensional, without evidencing any inner ambivalence. Often the women are reduced to the role of a simple threat to the man's identity, or the object of some infidelity, thereby catalysing the successes or failings of the male's existence, so providing the male protagonist an object for his own introspection. For the most part, the action in the male:female relationship in a work by Frisch comes from the woman, while the man remains passive, waiting and reflective. Superficially the woman is loved by the man, but in truth she is feared and despised.[58]

From her thoughtfully feminist perspective, Karin Struck saw Frisch's male protagonists manifesting a high level of dependency on the female characters, but the women remain strangers to them. The men are, from the outset, focused on the ending of the relationship: they cannot love because they are preoccupied with escaping from their own failings and anxieties. Often they conflate images of womanliness with images of death, as in Frisch's take on the Don Juan legend: "The woman reminds me of death, the more she seems to blossom and thrive".[59][60] Each new relationship with a woman, and the subsequent separation was, for a Frisch male protagonist, analogous to a bodily death: his fear of women corresponded with fear of death, which meant that his reaction to the relationship was one of flight and shame.[61]

Transience and death

Death is an ongoing theme in Frisch's work, but during his early and high periods it remains in the background, overshadowed by identity issues and relationship problems. Only with his later works does Death become a core question. Frisch's second published Diary (Tagebuch) launches the theme. A key sentence from the Diary 1966–1971 (published 1972), repeated several times, is a quotation from Montaigne:"So I dissolve; and I lose myself"[62][63][64] The section focuses on the private and social problems of aging. Although political demands are incorporated, social aspects remain secondary to the central concentration on the self. The Diary's fragmentary and hastily structured informality sustains a melancholy underlying mood.

The narrative Montauk (1975) also deals with old age. The autobiographically drawn protanonist's lack of much future throws the emphasis back onto working through the past and an urge to live for the present. In the drama-piece, Triptychon, Death is presented not necessarily directly, but as a way of referencing life metaphorically. Death reflects the ossification of human community, and in this way becomes a device for shaping lives. The narrative Man in the Holocene presents the dying process of an old man as a return to nature. According to Cornelia Steffahn there is no single coherent image of death presented in Frisch's late works. Instead they describe the process of his own evolving engagement with the issue, and show the way his own attitudes developed as he himself grew older. Along the way he works through a range of philosophical influences including Montaigne, Kierkegaard, Lars Gustafsson and even Epicurus.[65]

Political aspects

Frisch's early works were almost entirely apolitical. In the "Blätter aus dem Brotsack" ("diaries of military life") published in 1940, he comes across as a conventional Swiss patriot, reflecting the unifying impact on Swiss society of the perceived invasion risk then emanating from Germany. After 1945 the threat to Swiss values and to the independence of the Swiss state diminished. Frisch now underwent a rapid transformation, evincing a committed political consciousness. In particular, he became highly critical of attempts to divide cultural values from politics, noting in his Diary 1946–1949: "He who does not engage with politics is already a partisan of the political outcome that he wishes to preserve, because he is serving the ruling party"[66][67] Sonja Rüegg, writing in 1998, says that Frisch's aesthetics are driven by a fundamentally anti-ideological and critical animus, formed from a recognition of the writer's status as an outsider within society. That generates opposition to the ruling order, the privileging of individual partisanship over activity on behalf of a social class, and an emphasis on asking questions.[68]

Frisch's social criticism was particularly sharp in respect of his Swiss homeland. In a much quoted speech that he gave when accepting the 1973 Schiller Prize he declared: "I am Swiss, not simply because I hold a Swiss passport, was born on Swiss soil etc.: But I am Swiss by quasi-religious confession."[69] There followed a qualification: "Your homeland is not merely defined as a comfort or a convenience. 'Homeland' means more than that".[70][71] Frisch's very public verbal assaults on the land of his birth, on the country's public image of itself and on the unique international role of Switzerland emerged in his polemical, "Achtung: Die Schweiz", and extended to a work titled, Wilhelm Tell für die Schule (William Tell for Schools) which sought to deconstruct the defining epic of the nation, reducing the William Tell legend to a succession of coincidences, miscalculations, dead-ends and opportunistic gambits. With his Little service book (Dienstbüchlein) (1974) Frisch revisited and re-evaluated his own period of service in the nation's citizen army, and shortly before he died he went so far as to question outright the need for the army in Switzerland without an Army? A Palaver.

A characteristic pattern in Frisch's life was the way that periods of intense political engagement alternated with periods of retreat back to private concerns. Bettina Jaques-Bosch saw this as a succession of slow oscillations by the author between public outspokenness and inner melancholy.[72] Hans Ulrich Probst positioned the mood of the later works somewhere "between resignation and the radicalism of an old republican"[73] The last sentences published by Frisch are included in a letter addressed to the high-profile entrepreneur Marco Solari and published in the left of centre Wochenzeitung (weekly newspaper), and here he returned one last time to attacking the Swiss state: "1848 was a great creation of free-thinking Liberalism which today, after a century of domination by a middle-class coalition, has become a squandered state – and I am still bound to this state by one thing: a passport (which I shall not be needing again)".[74][75]

Recognition

Success as a writer and as a dramatist

Interviewed in 1975, Frisch acknowledged that his literary career had not been marked by some "sudden breakthrough" ("...frappanten Durchbruch") but that success had arrived, as he asserted, only very slowly.[76] Nevertheless, even his earlier publications were not entirely without a certain success. In his 20s he was already having pieces published in various newspapers and journals. As a young writer he also had work accepted by an established publishing house, the Munich based Deutschen Verlags-Anstalt, which already included a number of distinguished German-language authors on its lists. When he decided he no longer wished to have his work published in Nazi Germany he changed publishers, joining up with Atlantis Verlag which had relocated their head office from Berlin to Zürich in response to the political changes in Germany. In 1950 Frisch switched publishers again, this time to the arguably more mainstream publishing house then being established in Frankfurt by Peter Suhrkamp.

Frisch was still only in his early 30s when he turned to drama, and his stage work found ready acceptance at the Zürich Playhouse, at this time one of Europe's leading theatres, the quality and variety its work much enhanced by an influx of artistic talent since the mid-1930s from Germany. Frisch's early plays, performed at Zürich, were positively reviewed and won prizes. It was only in 1951, with Prince Öderland, that Frisch experienced his first stage-flop.[77] The experience encouraged him to pay more attention to audiences outside his native Switzerland, notably in the new and rapidly developing Federal Republic of Germany, where the novel I'm Not Stiller succeeded commercially on a scale that till then had eluded Frisch, enabling him now to become a full-time professional writer.[78]

I'm Not Stiller started with a print-run that provided for sales of 3,000 in its first year,[76] but thanks to strong and growing reader demand it later became the first book published by Suhrkamp to top one million copies.[79] The next novel, Homo Faber, was another best seller, with four million copies of the German language version produced by 1998.[80] The Fire Raisers and Andorra are the most successful German language plays of all time, with respectively 250 and 230 productions up till 1996, according to an estimate made by the literary critic Volker Hage.[81] The two plays, along with Homo Faber became curriculum favourites with schools in the German-speaking middle European countries. Apart from a few early works, most of Frisch's books and plays have been translated into around ten languages, while the most translated of all, Homo Faber, has been translated into twenty-five languages.

Reputation in Switzerland and internationally

Frisch's name is often mentioned along with that of another great writer of his generation, Friedrich Dürrenmatt.

The scholar Hans Mayer likened them to the mythical half-twins, Castor and Pollux, as two dialectically linked "antagonists".[82] The close friendship of their early careers was later overshadowed by personal differences. In 1986 Dürrenmatt took the opportunity of Frisch's 75th birthday to try and effect a reconciliation with a letter, but the letter went unanswered.[83][84] In their approaches the two were very different. The literary journalist Heinz Ludwig Arnold quipped that Dürrenmatt, despite all his narrative work, was born to be a dramatist, while Frisch, his theatre successes notwithstanding, was born to be a writer of narratives.

In the 1960s, by publicly challenging some contradictions and settled assumptions, both Frisch und Dürrenmatt contributed to a major revision in Switzerland‘s view if itself and of its history. In 1974 Frisch published his Little service book (Dienstbüchlein), and from this time – possibly from earlier – Frisch became a powerfully divisive figure in Switzerland, where in some quarters his criticisms were vigorously rejected. For aspiring writers seeking a role model, most young authors preferred Frisch over Dürrenmatt as a source of instruction and enlightenment, according to Janos Szábo. In the 1960s Frisch inspired a generation of younger writers including Peter Bichsel, Jörg Steiner, Otto F. Walter, and Adolf Muschg. More than a generation after that, in 1998, when it was the turn of Swiss literature to be the special focus [85] at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the literary commentator Andreas Isenschmid identified some leading Swiss writers from his own (baby-boomer) generation such as Ruth Schweikert, Daniel de Roulet and Silvio Huonder in whose works he had found "a curiously familiar old tone, resonating from all directions, and often almost page by page, uncanny echoes from Max Frisch's Stiller.[86][87][88]

The works of Frisch were also important in West Germany. The West German essayist and critic Heinrich Vormweg described I'm Not Stiller and Homo Faber as "two of the most significant and influential German-language novels of the 1950s".[89][90] In East Germany during the 1980s Frisch's prose works and plays also ran through many editions, although here they were not the focus of so much intensive literary commentary. Translations of Frisch's works into the languages of other formally socialist countries in the Eastern Bloc were also widely available, leading the author himself to offer the comment that in the Soviet Union his works were officially seen as presenting the "symptoms of a sick capitalist society, symptoms that would never be found where the means of production have been nationalized"[91][92] Despite some ideologically driven official criticism of his "individualism", "negativity" and "modernism", Frisch's works were actively translated into Russian, and were featured in some 150 reviews in the Soviet Union.[93] Frisch also found success in his second "homeland of choice", the United States where he lived, off and on, for some time during his later years. He was generally well regarded by the New York literary establishment: one commentator found him commendably free of "European arrogance".[94]

Influence and significance

Jürgen H. Petersen reckons that Frisch's stage work had little influence on other dramatists. And his own preferred form of the "literary diary" failed to create a new trend in literary genres. By contrast, the novels I'm Not Stiller and Gantenbein have been widely taken up as literary models, both because of the way they home in on questions of individual identity and on account of their literary structures. Issues of personal identity are presented not simply through description or interior insights, but through narrative contrivances. This stylistic influence can be found frequently in the works of others, such as Christa Wolf's The Quest for Christa T. and in Ingeborg Bachmann's Malina. Other similarly influenced authors are Peter Härtling and Dieter Kühn. Frisch also found himself featuring as a character in the literature of others. That was the case in 1983 with Wolfgang Hildesheimer's Message to Max [Frisch] about the state of things and other matters (Mitteilungen an Max über den Stand der Dinge und anderes). By then Uwe Johnson had already, in 1975, produced a compilation of quotations which he called "The collected sayings of Max Frisch" ("Max Frisch Stich-Worte zusammen").[95] More recently, in 2007, the Zürich–born artist Gottfried Honegger published eleven portrait-sketches and fourteen texts in memory of his friend.[96]

Adolf Muschg, purporting to address Frisch directly on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, contemplates the older man's contribution: "Your position in the history of literature, how can it be described? You have not been, in conventional terms, an innovator… I believe you have defined an era through something both unobtrusive and fundamental: a new experimental ethos (and pathos). Your books form deep literary investigation from an act of the imagination."[97][98] Marcel Reich-Ranicki saw similarities with at least some of the other leading German-language writers of his time: "Unlike Dürrenmatt or Böll, but in common with Grass and Uwe Johnson, Frisch wrote about the complexes and conflicts of intellectuals, returning again and again to us, creative intellectuals from the ranks of the educated middle-classes: no one else so clearly identified and saw into our mentality.[99][100] Friedrich Dürrenmatt marvelled at his colleague: "the boldness with which he immediately launches out with utter subjectivity. He is himself always at the heart of the matter. His matter is the matter.[101] In Dürrenmatt's last letter to Frisch he coined the formulation that Frisch in his work had made "his case to the world".[102][103]

Film

The film director Alexander J. Seiler believes that Frisch had for the most part an "unfortunate relationship" with film, even though his literary style is often reminiscent of cinematic technique. Seiler explains that Frisch's work was often, in the author's own words, looking for ways to highlight the "white space" between the words, which is something that can usually only be achieved using a film-set. Already, in the Diary 1946–1949 there is an early sketch for a film-script, titled Harlequin.[104] His first practical experience of the genre came in 1959, but with a project that was nevertheless abandoned, when Frisch resigned from the production of a film titled SOS Gletscherpilot (SOS Glacier Pilot),[105] and in 1960 his draft script for William Tell (Castle in Flames) was turned down, after which the film was created anyway, totally contrary to Frisch's intentions. In 1965 there were plans, under the Title Zürich – Transit, to film an episode from the novel Gantenbein, but the project was halted, initially by differences between Frisch and the film director Erwin Leiser and then, it was reported, by the illness of Bernhard Wicki who was brought in to replace Leiser. The Zürich – Transit project went ahead in the end, directed by Hilde Bechart, but only in 1992 a quarter century later, and a year after Frisch had died.

For the novels I'm Not Stiller and Homo Faber there were several film proposals, one of which involved casting the actor Anthony Quinn in Homo Faber, but none of these proposals was ever realised. It is nevertheless interesting that several of Frisch's dramas were filmed for television adaptations. It was in this way that the first filmic adaptation of a Frisch prose work appeared in 1975, thanks to Georg Radanowicz, and titled The Misfortune (Das Unglück). This was based on a sketch from one of Frisch's Diaries.[106] It was followed in 1981 by a Richard Dindo television production based on the narrative Montauk [107] and one by Krzysztof Zanussi based on Bluebeard.[108] It finally became possible, some months after Frisch's death, for a full-scale cinema version of Homo Faber to be produced. While Frisch was still alive he had collaborated with the filmmaker Volker Schlöndorff on this production, but the critics were nevertheless underwhelmed by the result.[109] In 1992, however, Holozän, a film adaptation by Heinz Bütler and Manfred Eicher of Man in the Holocene, received a "special award" at the Locarno International Film Festival.[110]

Recognition

- 1935: Prize for a single work for Jürg Reinhart from the Swiss Schiller Foundation

- 1938: Conrad Ferdinand Meyer Prize (Zürich)

- 1940: Prize for a single work for "Pages from the Bread-bag" ("Blätter aus dem Brotsack") from the Swiss Schiller Foundation

- 1942: First (out of 65 entrants) in an architecture contest (Zürich: Freibad Letzigraben)

- 1945: Welti Foundation Drama prize for Santa Cruz

- 1954: Wilhelm Raabe prize (Braunschweig) for Stiller

- 1955: Prize for all works to date from the Swiss Schiller Foundation

- 1955: Schleußner Schueller prize from Hessischer Rundfunk (Hessian Broadcasting Corporation)

- 1958: Georg Büchner Prize

- 1958: Charles Veillon Prize (Lausanne) for Stiller and Homo Faber[111]

- 1958: Literature Prize of the City of Zürich

- 1962: Honorary doctorate from the Philipp University of Marburg

- 1962: Major art prize of the City of Düsseldorf

- 1965: Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in Society

- 1965: Schiller Memorial Prize (Baden-Württemberg)

- 1973: Major Schiller Prize from the Swiss Schiller Foundation[112]

- 1976: Peace Prize of the German Book Trade [113]

- 1979: Gift of honour from the "Literaturkredit" of the Canton of Zürich (rejected!)

- 1980: Honorary doctorate from Bard College (New York state)

- 1982: Honorary doctorate from the City University of New York

- 1984: Honorary doctorate from the University of Birmingham

- 1984: Nominated a Commander, Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France)

- 1986: Neustadt International Prize for Literature from the University of Oklahoma

- 1987: Honorary doctorate from the Technical University of Berlin

- 1989: Heinrich Heine Prize (Düsseldorf)

Frisch was awarded honorary degrees by the University of Marburg, Germany, in 1962, Bard College (1980), the City University of New York (1982), the University of Birmingham (1984), and the TU Berlin (1987).

He also won many important German literature prizes: the Georg-Büchner-Preis in 1958, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels) in 1976, and the Heinrich-Heine-Preis in 1989.

In 1965 he won the Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in Society.

The City of Zürich introduced the Max-Frisch-Preis in 1998 to celebrate the author's memory. The prize is awarded every four years and comes with a CHF 50,000 payment to the winner.

The 100th anniversary of Frisch's birth took place in 2011 and was marked by an exhibition in his home city of Zürich. The occasion was also celebrated by an exhibition at the Munich Literature Centre which carried the suitably enigmatic tagline, "Max Frisch. Heimweh nach der Fremde" and another exhibition at the Museo Onsernonese in Loco, close to the Ticinese cottage to which Frisch regularly retreated over several decades.

In 2015 it is intended to name a new city-square in Zürich Max-Frisch-Platz. This is part of a larger urban redevelopment scheme which is being coordinated with a major building project underway to expand Zürich Oerlikon railway station.[114]

Major works

Novels

- Antwort aus der Stille (1937, An Answer from the Silence)

- Stiller (1954, I'm Not Stiller)

- Homo Faber (1957)

- Mein Name sei Gantenbein (1964, Gantenbein / A Wilderness of Mirrors)

- Dienstbüchlein (1974)

- Montauk (1975)

- Der Mensch erscheint im Holozän (1979, Man in the Holocene)

- Blaubart (1982, Bluebeard)

- Wilhelm Tell für die Schule (1971, Wilhelm Tell: A School Text, published in Fiction Magazine 1978)

Journals

- Blätter aus dem Brotsack (1939)

- Tagebuch 1946–1949 (1950)

- Tagebuch 1966–1971 (1972)

Plays

- Nun singen sie wieder (1945)

- Santa Cruz (1947)

- Die Chinesische Mauer (1947, The Chinese Wall)

- Als der Krieg zu Ende war (1949, When the War Was Over)

- Graf Öderland (1951)

- Biedermann und die Brandstifter (1953, Firebugs)

- Don Juan oder Die Liebe zur Geometrie (1953)

- Die Grosse Wut des Philipp Hotz (1956)

- Andorra (1961)

- Biografie (1967)

- Triptychon. Drei szenische Bilder (1978)

- Jonas und sein Veteran (1989)

References

- ↑ Frish, Max (1911–1991). In Suzanne M. Bourgoin and Paula K. Byers, Encyclopedia of World Biography. Detroit: Gale Research, 1998. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ Waleczek 2001.

- ↑ Waleczek 2001, p. 21.

- ↑ Waleczek 2001, p. 23.

- ↑ Lioba Waleczek. Max Frisch. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2001, p. 36.

- ↑ Waleczek 2001, p. 39.

- ↑ Waleczek, p. 23.

- ↑ In an interview in 1978 Frisch explained:

"Falling in love with a Jewish girl in Berlin before the war saved me, or made it impossible for me, to embrace Hitler or any form of fascism."

("Dass ich mich in Berlin vor dem Krieg in ein jüdisches Mädchen verliebt hatte, hat mich davor bewahrt, oder es mir unmöglich gemacht, Hitler oder jegliche Art des Faschismus zu begrüßen.")

- as quoted in: Alexander Stephan. Max Frisch. In Heinz Ludwig Arnold (ed.): Kritisches Lexikon zur deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur 11th ed., München: Ed. Text + Kritik, 1992. - ↑ Ursula Priess. Sturz durch alle Spiegel: Eine Bestandsaufnahme. Zürich: Ammann, 2009, 178 S., ISBN 978-3-250-60131-9.

- ↑ Urs Bircher. Vom langsamen Wachsen eines Zorns: Max Frisch 1911–1955. Zürich: Limmat, 1997, p. 220.

- ↑ Bircher, p. 211.

- ↑ Lioba Waleczek: Max Frisch. p. 70.

- ↑ Lioba Waleczek: Max Frisch. p. 74.

- ↑ Urs Bircher: Vom langsamen Wachsen eines Zorns: Max Frisch 1911–1955. p. 104.

- ↑ Lioba Waleczek: Max Frisch. p. 101.

- ↑ Butler, Michael (2004). "Identity and authenticity in postwar Swiss and Austrian novels". In Bartram, Graham. The Cambridge Companion to the Modern German Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 0-521-48253-4.

- 1 2 Bernadette Conrad (12 May 2011). "Sein letztes Refugium: Vor 100 Jahren wurde er geboren – ein Zuhause fand Max Frisch erst spät, in einer wilden Gegend des Tessins.". Die Zeit (Zeit On-line). Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ↑ »Siebenmal im Jahr fahren wir diese Strecke, und es tritt jedes Mal ein: Daseinslust am Steuer. Das ist eine große Landschaft.«

- ↑ "Nein, Mao habe ich nicht gesehen: Max Frisch mit Kanzler Helmut Schmidt in China". Der Spiegel. 9 February 1976. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 Volker Hage (5 March 2011). "Im Mai dieses Jahres wäre Max Frisch 100 Jahre alt geworden. Karin Pilliod, die letzte Lebensgefährtin des großen Schweizer Schriftstellers, erzählt erstmals von ihrer Beziehung und deren wenig bekannter Vorgeschichte". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ↑ Jürgen Habermas (10 February 2007). "Ein Bewusstsein von dem, was fehlt: "... Die Trauergemeinde bestand aus Intellektuellen, von denen die meisten mit Religion und Kirche nicht viel im Sinn hatten. Für das anschliessende Essen hatte Frisch selbst noch das Menu zusammengestellt."". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ↑ Jürgen Habermas (10 February 2007). "Ein Bewusstsein von dem, was fehlt: Über Glauben und Wissen und den Defaitismus der modernen Vernunft". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ↑ Rolf Kieser: Das Tagebuch als Idee und Struktur im Werke Max Frischs. In: Walter Schmitz (Hrsg.): Max Frisch. Materialien. Suhrkamp, 1987. ISBN 3-518-38559-3. Seite 21.

- 1 2 "Sekretärin findet unbekanntes Max-Frisch-Tagebuch:

Der Suhrkamp Verlag will im März 2010 ein bisher unbekanntes Werk von Max Frisch veröffentlichen. Gefunden wurde dieses in den Unterlagen von Frischs Sekretärin.". Der Tages-Anzeiger. 18 March 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2014. - ↑ Alexander Stephan: Max Frisch. In Heinz Ludwig Arnold (Hrsg.): Kritisches Lexikon zur deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur 11. Nachlieferung, Edition text+kritik, Stand 1992. Seite 21.

- 1 2 Sybille Heidenreich: Max Frisch. Mein Name sei Gantenbein. Montauk. Stiller. Untersuchungen und Anmerkungen. Joachim Beyer Verlag, 2. Auflage 1978. ISBN 3-921202-19-1. p. 126.