Franz Kafka

| Franz Kafka | |

|---|---|

Kafka in 1906 | |

| Born |

3 July 1883 Prague, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary (now Czech Republic) |

| Died |

3 June 1924 (aged 40) Kierling, part of Klosterneuburg, Lower Austria, Austria |

| Citizenship | Austria-Hungary, Czechoslovakia[1][2] |

| Alma mater | German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague |

| Occupation |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Style | Modernism |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Signature | |

|

| |

Franz Kafka[lower-alpha 1] (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a German-language writer of novels and short stories who is widely regarded as one of the major figures of 20th-century literature. His work, which fuses elements of realism and the fantastic,[3] typically features isolated protagonists faced by bizarre or surrealistic predicaments and incomprehensible social-bureaucratic powers, and has been interpreted as exploring themes of alienation, existential anxiety, guilt, and absurdity.[4] His best known works include "Die Verwandlung" ("The Metamorphosis"), Der Process (The Trial), and Das Schloss (The Castle). The term Kafkaesque has entered the English language to describe situations like those in his writing.[5]

Kafka was born into a middle-class, German-speaking Jewish family in Prague, the capital of the Kingdom of Bohemia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He trained as a lawyer, and after completing his legal education he was employed with an insurance company, forcing him to relegate writing to his spare time. Over the course of his life, Kafka wrote hundreds of letters to family and close friends, including his father, with whom he had a strained and formal relationship. He died in 1924 at the age of 40 from tuberculosis.

Few of Kafka's works were published during his lifetime: the story collections Betrachtung (Contemplation) and Ein Landarzt (A Country Doctor), and individual stories (such as "Die Verwandlung") were published in literary magazines but received little public attention. Kafka's unfinished works, including his novels Der Process, Das Schloss and Amerika (also known as Der Verschollene, The Man Who Disappeared), were ordered by Kafka to be destroyed by his friend Max Brod, who nonetheless ignored his friend's direction and published them after Kafka's death.

Life

Family

Kafka was born near the Old Town Square in Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His family were middle-class Ashkenazi Jews. His father, Hermann Kafka (1852–1931), was the fourth child of Jakob Kafka,[6][7] a shochet or ritual slaughterer in Osek, a Czech village with a large Jewish population located near Strakonice in southern Bohemia.[8] Hermann brought the Kafka family to Prague. After working as a travelling sales representative, he eventually became a fancy goods and clothing retailer who employed up to 15 people and used the image of a jackdaw (kavka in Czech, pronounced and colloquially written as kafka) as his business logo.[9] Kafka's mother, Julie (1856–1934), was the daughter of Jakob Löwy, a prosperous retail merchant in Poděbrady,[10] and was better educated than her husband.[6]

.jpg)

Kafka's parents probably spoke a German influenced by Yiddish that was sometimes pejoratively called Mauscheldeutsch, but, as the German language was considered the vehicle of social mobility, they probably encouraged their children to speak High German.[11] Hermann and Julie had six children, of whom Franz was the eldest.[12] Franz's two brothers, Georg and Heinrich, died in infancy before Franz was seven; his three sisters were Gabriele ("Ellie") (1889–1944), Valerie ("Valli") (1890–1942) and Ottilie ("Ottla") (1892–1943). They all died during the Holocaust of World War II. Valli was deported to the Łódź Ghetto in Poland in 1942, but that is the last documentation of her.

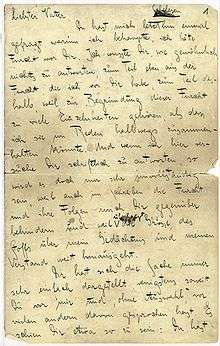

Hermann is described by the biographer Stanley Corngold as a "huge, selfish, overbearing businessman"[13] and by Franz Kafka as "a true Kafka in strength, health, appetite, loudness of voice, eloquence, self-satisfaction, worldly dominance, endurance, presence of mind, [and] knowledge of human nature".[14] On business days, both parents were absent from the home, with Julie Kafka working as many as 12 hours each day helping to manage the family business. Consequently, Kafka's childhood was somewhat lonely,[15] and the children were reared largely by a series of governesses and servants. Kafka's troubled relationship with his father is evident in his Brief an den Vater (Letter to His Father) of more than 100 pages, in which he complains of being profoundly affected by his father's authoritarian and demanding character;[16] his mother, in contrast, was quiet and shy.[17] The dominating figure of Kafka's father had a significant influence on Kafka's writing.[18]

The Kafka family had a servant girl living with them in a cramped apartment. Franz's room was often cold. In November 1913 the family moved into a bigger apartment, although Ellie and Valli had married and moved out of the first apartment. In early August 1914, just after World War I began, the sisters did not know where their husbands were in the military and moved back in with the family in this larger apartment. Both Ellie and Valli also had children. Franz at age 31 moved into Valli's former apartment, quiet by contrast, and lived by himself for the first time.[19]

Education

From 1889 to 1893, Kafka attended the Deutsche Knabenschule German boys' elementary school at the Masný trh/Fleischmarkt (meat market), now known as Masná Street. His Jewish education ended with his Bar Mitzvah celebration at the age of 13. Kafka never enjoyed attending the synagogue and went with his father only on four high holidays a year.[14][20][21]

After leaving elementary school in 1893, Kafka was admitted to the rigorous classics-oriented state gymnasium, Altstädter Deutsches Gymnasium, an academic secondary school at Old Town Square, within the Kinský Palace. German was the language of instruction, but Kafka also spoke and wrote in Czech.[22][23] He studied the latter at the gymnasium for eight years, achieving good grades.[24] Although Kafka received compliments for his Czech, he never considered himself fluent in Czech, though he spoke German with a Czech accent.[1][23] He completed his Matura exams in 1901.[25]

Admitted to the Deutsche Karl-Ferdinands-Universität of Prague in 1901, Kafka began studying chemistry, but switched to law after two weeks.[26] Although this field did not excite him, it offered a range of career possibilities which pleased his father. In addition, law required a longer course of study, giving Kafka time to take classes in German studies and art history.[27] He also joined a student club, Lese- und Redehalle der Deutschen Studenten (Reading and Lecture Hall of the German students), which organized literary events, readings and other activities.[28] Among Kafka's friends were the journalist Felix Weltsch, who studied philosophy, the actor Yitzchak Lowy who came from an orthodox Hasidic Warsaw family, and the writers Oskar Baum and Franz Werfel.[29]

At the end of his first year of studies, Kafka met Max Brod, a fellow law student who became a close friend for life.[28] Brod soon noticed that, although Kafka was shy and seldom spoke, what he said was usually profound.[30] Kafka was an avid reader throughout his life;[31] together he and Brod read Plato's Protagoras in the original Greek, on Brod's initiative, and Flaubert's L'éducation sentimentale and La Tentation de St. Antoine (The Temptation of Saint Anthony) in French, at his own suggestion.[32] Kafka considered Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Flaubert, Nikolai Gogol, Franz Grillparzer,[33] and Heinrich von Kleist to be his "true blood brothers".[34] Besides these, he took an interest in Czech literature[22][23] and was also very fond of the works of Goethe.[35][36] Kafka was awarded the degree of Doctor of Law on 18 July 1906[lower-alpha 2] and performed an obligatory year of unpaid service as law clerk for the civil and criminal courts.[5]

Employment

On 1 November 1907, Kafka was hired at the Assicurazioni Generali, an Italian insurance company, where he worked for nearly a year. His correspondence during that period indicates that he was unhappy with a working time schedule—from 08:00 until 18:00[39][40]—making it extremely difficult to concentrate on writing, which was assuming increasing importance to him. On 15 July 1908, he resigned. Two weeks later he found employment more amenable to writing when he joined the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia. The job involved investigating and assessing compensation for personal injury to industrial workers; accidents such as lost fingers or limbs were commonplace at this time. The management professor Peter Drucker credits Kafka with developing the first civilian hard hat while employed at the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute, but this is not supported by any document from his employer.[41][42] His father often referred to his son's job as an insurance officer as a Brotberuf, literally "bread job", a job done only to pay the bills; Kafka often claimed to despise it. Kafka was rapidly promoted and his duties included processing and investigating compensation claims, writing reports, and handling appeals from businessmen who thought their firms had been placed in too high a risk category, which cost them more in insurance premiums.[43] He would compile and compose the annual report on the insurance institute for the several years he worked there. The reports were received well by his superiors.[44] Kafka usually got off work at 2 p.m., so that he had time to spend on his literary work, to which he was committed.[45] Kafka's father also expected him to help out at and take over the family fancy goods store.[46] In his later years, Kafka's illness often prevented him from working at the insurance bureau and at his writing. Years later, Brod coined the term Der enge Prager Kreis ("The Close Prague Circle") to describe the group of writers, which included Kafka, Felix Weltsch and him.[47][48]

In late 1911, Elli's husband Karl Hermann and Kafka became partners in the first asbestos factory in Prague, known as Prager Asbestwerke Hermann & Co., having used dowry money from Hermann Kafka. Kafka showed a positive attitude at first, dedicating much of his free time to the business, but he later resented the encroachment of this work on his writing time.[49] During that period, he also found interest and entertainment in the performances of Yiddish theatre. After seeing a Yiddish theater troupe perform in October 1911, for the next six months Kafka "immersed himself in Yiddish language and in Yiddish literature".[50] This interest also served as a starting point for his growing exploration of Judaism.[51] It was at about this time that Kafka became a vegetarian.[52] Around 1915 Kafka received his draft notice for military service in World War I, but his employers at the insurance institute arranged for a deferment because his work was considered essential government service. Later he attempted to join the military but was prevented from doing so by medical problems associated with tuberculosis,[53] with which he was diagnosed in 1917.[54] In 1918 the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute put Kafka on a pension due to his illness, for which there was no cure at the time, and he spent most of the rest of his life in sanatoriums.[5]

Private life

Kafka was never married. According to Brod, Kafka was "tortured" by sexual desire[55] and Kafka's biographer Reiner Stach states that his life was full of "incessant womanising" and that he was filled with a fear of "sexual failure".[56] He visited brothels for most of his adult life[57][58][59] and was interested in pornography.[55] In addition, he had close relationships with several women during his life. On 13 August 1912, Kafka met Felice Bauer, a relative of Brod, who worked in Berlin as a representative of a dictaphone company. A week after the meeting at Brod's home, Kafka wrote in his diary:

Miss FB. When I arrived at Brod's on 13 August, she was sitting at the table. I was not at all curious about who she was, but rather took her for granted at once. Bony, empty face that wore its emptiness openly. Bare throat. A blouse thrown on. Looked very domestic in her dress although, as it turned out, she by no means was. (I alienate myself from her a little by inspecting her so closely ...) Almost broken nose. Blonde, somewhat straight, unattractive hair, strong chin. As I was taking my seat I looked at her closely for the first time, by the time I was seated I already had an unshakeable opinion.[60][61]

Shortly after this, Kafka wrote the story "Das Urteil" ("The Judgment") in only one night and worked in a productive period on Der Verschollene (The Man Who Disappeared) and "Die Verwandlung" ("The Metamorphosis"). Kafka and Felice Bauer communicated mostly through letters over the next five years, met occasionally, and were engaged twice.[62] Kafka's extant letters to her were published as Briefe an Felice (Letters to Felice); her letters do not survive.[60][63][64] According to biographers Stach and James Hawes, around 1920 Kafka was engaged a third time, to Julie Wohryzek, a poor and uneducated hotel chambermaid.[62][65] Although the two rented a flat and set a wedding date, the marriage never took place. During this time Kafka began a draft of the Letter to His Father, who objected to Julie because of her Zionist beliefs. Before the date of the intended marriage, he took up with yet another woman.[66] While he needed women and sex in his life, he had low self-confidence, felt sex was dirty, and was shy—especially about his body.[5]

Stach and Brod state that during the time that Kafka knew Felice Bauer, he had an affair with a friend of hers, Margarethe "Grete" Bloch,[67] a Jewish woman from Berlin. Brod says that Bloch gave birth to Kafka's son, although Kafka never knew about the child. The boy, whose name is not known, was born in 1914 or 1915 and died in Munich in 1921.[68][69] However, Kafka's biographer Peter-André Alt claims that, while Bloch had a son, Kafka was not the father as the pair were never intimate.[70][71] Stach states that Bloch had a son, but there is not solid proof but contradictory evidence that Kafka was the father.[72]

Kafka was diagnosed with tuberculosis in August 1917 and moved for a few months to the Bohemian village of Zürau (Siřem in the Czech language), where his sister Ottla worked on the farm of her brother-in-law Hermann. He felt comfortable there and later described this time as perhaps the best time in his life, probably because he had no responsibilities. He kept diaries and Oktavhefte (octavo). From the notes in these books, Kafka extracted 109 numbered pieces of text on Zettel, single pieces of paper in no given order. They were later published as Die Zürauer Aphorismen oder Betrachtungen über Sünde, Hoffnung, Leid und den wahren Weg (The Zürau Aphorisms or Reflections on Sin, Hope, Suffering, and the True Way).[73]

In 1920 Kafka began an intense relationship with Milena Jesenská, a Czech journalist and writer. His letters to her were later published as Letters to Milena.[74] During a vacation in July 1923 to Graal-Müritz on the Baltic Sea, Kafka met Dora Diamant, a 25-year-old kindergarten teacher from an orthodox Jewish family. Kafka, hoping to escape the influence of his family to concentrate on his writing, moved briefly to Berlin and lived with Diamant. She became his lover and caused him to become interested in the Talmud.[75] He worked on four stories, which he prepared to be published as Ein Hungerkünstler (A Hunger Artist).[74]

Personality

Kafka feared that people would find him mentally and physically repulsive. However, those who met him found him to possess a quiet and cool demeanor, obvious intelligence, and a dry sense of humour; they also found him boyishly handsome, although of austere appearance.[76][77][78] Brod compared Kafka to Heinrich von Kleist, noting that both writers had the ability to describe a situation realistically with precise details.[79] Brod thought Kafka was one of the most entertaining people he had met; Kafka enjoyed sharing humour with his friends, but also helped them in difficult situations with good advice.[80] According to Brod, he was a passionate reciter, who was able to phrase his speaking as if it were music.[81] Brod felt that two of Kafka's most distinguishing traits were "absolute truthfulness" (absolute Wahrhaftigkeit) and "precise conscientiousness" (präzise Gewissenhaftigkeit).[82][83] He explored details, the inconspicuous, in depth and with such love and precision that things surfaced that were unforeseen, seemingly strange, but absolutely true (nichts als wahr).[84]

Although Kafka showed little interest in exercise as a child, he later showed interest in games and physical activity,[31] as a good rider, swimmer, and rower.[82] On weekends he and his friends embarked on long hikes, often planned by Kafka himself.[85] His other interests included alternative medicine, modern education systems such as Montessori,[82] and technical novelties such as airplanes and film.[86] Writing was important to Kafka; he considered it a "form of prayer".[87] He was highly sensitive to noise and preferred quiet when writing.[88]

Pérez-Álvarez has claimed that Kafka may have possessed a schizoid personality disorder.[89] His style, it is claimed, not only in "Die Verwandlung" ("The Metamorphosis"), but in various other writings, appears to show low to medium-level schizoid traits, which explain much of his work.[90] His anguish can be seen in this diary entry from 21 June 1913:[91]

The tremendous world I have in my head. But how to free myself and free them without ripping apart. And a thousand times rather tear in me they hold back or buried. For this I'm here, that's quite clear to me.[92]

and in Zürau Aphorism number 50:

Man cannot live without a permanent trust in something indestructible within himself, though both that indestructible something and his own trust in it may remain permanently concealed from him.[93]

Though Kafka never married, he held marriage and children in high esteem. He had several girlfriends.[94] He may have suffered from an eating disorder. Doctor Manfred M. Fichter of the Psychiatric Clinic, University of Munich, presented "evidence for the hypothesis that the writer Franz Kafka had suffered from an atypical anorexia nervosa",[95] and that Kafka was not just lonely and depressed but also "occasionally suicidal".[77] In his 1995 book Franz Kafka, the Jewish Patient, Sander Gilman investigated "why a Jew might have been considered 'hypochondriac' or 'homosexual' and how Kafka incorporates aspects of these ways of understanding the Jewish male into his own self-image and writing".[96] Kafka considered committing suicide at least once, in late 1912.[97]

Political views

Prior to World War I,[98] Kafka attended several meetings of the Klub Mladých, a Czech anarchist, anti-militarist, and anti-clerical organization.[99] Hugo Bergmann, who attended the same elementary and high schools as Kafka, fell out with Kafka during their last academic year (1900–1901) because "[Kafka's] socialism and my Zionism were much too strident".[100][101] "Franz became a socialist, I became a Zionist in 1898. The synthesis of Zionism and socialism did not yet exist".[101] Bergmann claims that Kafka wore a red carnation to school to show his support for socialism.[101] In one diary entry, Kafka made reference to the influential anarchist philosopher Peter Kropotkin: "Don't forget Kropotkin!"[102]

During the communist era, the legacy of Kafka's work for Eastern bloc socialism was hotly debated. Opinions ranged from the notion that he satirised the bureaucratic bungling of a crumbling Austria-Hungarian Empire, to the belief that he embodied the rise of socialism.[103] A further key point was Marx's theory of alienation. While the orthodox position was that Kafka's depictions of alienation were no longer relevant for a society that had supposedly eliminated alienation, a 1963 conference held in Liblice, Czechoslovakia, on the eightieth anniversary of his birth, reassessed the importance of Kafka's portrayal of bureaucracy.[104] Whether or not Kafka was a political writer is still an issue of debate.[105]

Judaism and Zionism

Kafka grew up in Prague as a German-speaking Jew.[106] He was deeply fascinated by the Jews of Eastern Europe, who he thought possessed an intensity of spiritual life that was absent from Jews in the West. His diary is full of references to Yiddish writers.[107] Yet he was at times alienated from Judaism and Jewish life: "What have I in common with Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself and should stand very quietly in a corner, content that I can breathe".[108] In his adolescent years, Kafka had declared himself an atheist.[109]

Hawes suggests that Kafka, though very aware of his own Jewishness, did not incorporate it into his work, which, according to Hawes, lacks Jewish characters, scenes or themes.[110][111][112] In the opinion of literary critic Harold Bloom, although Kafka was uneasy with his Jewish heritage, he was the quintessential Jewish writer.[113] Lothar Kahn is likewise unequivocal: "The presence of Jewishness in Kafka's oeuvre is no longer subject to doubt".[114] Pavel Eisner, one of Kafka's first translators, interprets Der Process (The Trial) as the embodiment of the "triple dimension of Jewish existence in Prague ... his protagonist Josef K. is (symbolically) arrested by a German (Rabensteiner), a Czech (Kullich), and a Jew (Kaminer). He stands for the 'guiltless guilt' that imbues the Jew in the modern world, although there is no evidence that he himself is a Jew".[115]

In his essay Sadness in Palestine?!, Dan Miron explores Kafka's connection to Zionism: "It seems that those who claim that there was such a connection and that Zionism played a central role in his life and literary work, and those who deny the connection altogether or dismiss its importance, are both wrong. The truth lies in some very elusive place between these two simplistic poles".[107] Kafka considered moving to Palestine with Felice Bauer, and later with Dora Diamant. He studied Hebrew while living in Berlin, hiring a friend of Brod's from Palestine, Pua Bat-Tovim, to tutor him[107] and attending Rabbi Julius Grünthal's[116] and Rabbi Julius Guttmann's classes in the Berlin Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums (College for the Study of Judaism).[117]

Livia Rothkirchen calls Kafka the "symbolic figure of his era".[115] His contemporaries included numerous Jewish, Czech, and German writers who were sensitive to Jewish, Czech, and German culture. According to Rothkirchen, "This situation lent their writings a broad cosmopolitan outlook and a quality of exaltation bordering on transcendental metaphysical contemplation. An illustrious example is Franz Kafka".[115]

Towards the end of his life Kafka sent a postcard to his friend Hugo Bergman in Tel Aviv, announcing his intention to emigrate to Palestine. Bergman refused to host Kafka because he had young children and was afraid that Kafka would infect them with tuberculosis.[118]

Death

Kafka's laryngeal tuberculosis worsened and in March 1924 he returned from Berlin to Prague,[62] where members of his family, principally his sister Ottla, took care of him. He went to Dr. Hoffmann's sanatorium in Kierling just outside Vienna for treatment on 10 April,[74] and died there on 3 June 1924. The cause of death seemed to be starvation: the condition of Kafka's throat made eating too painful for him, and since parenteral nutrition had not yet been developed, there was no way to feed him.[119][120] Kafka was editing "A Hunger Artist" on his deathbed, a story whose composition he had begun before his throat closed to the point that he could not take any nourishment.[121] His body was brought back to Prague where he was buried on 11 June 1924, in the New Jewish Cemetery in Prague-Žižkov.[58] Kafka was unknown during his own lifetime, but he did not consider fame important. He became famous soon after his death.[87] The Kafka tombstone was designed by architect Leopold Ehrmann.[122]

Works

All of Kafka's published works, except some letters he wrote in Czech to Milena Jesenská, were written in German. What little was published during his lifetime attracted scant public attention.

Kafka finished none of his full-length novels and burned around 90 percent of his work,[123][124] much of it during the period he lived in Berlin with Diamant, who helped him burn the drafts.[125] In his early years as a writer, he was influenced by von Kleist, whose work he described in a letter to Bauer as frightening, and whom he considered closer than his own family.[126]

Stories

Kafka's earliest published works were eight stories which appeared in 1908 in the first issue of the literary journal Hyperion under the title Betrachtung (Contemplation). He wrote the story "Beschreibung eines Kampfes" ("Description of a Struggle")[lower-alpha 3] in 1904; he showed it to Brod in 1905 who advised him to continue writing and convinced him to submit it to Hyperion. Kafka published a fragment in 1908[127] and two sections in the spring of 1909, all in Munich.[128]

In a creative outburst on the night of 22 September 1912, Kafka wrote the story "Das Urteil" ("The Judgment", literally: "The Verdict") and dedicated it to Felice Bauer. Brod noted the similarity in names of the main character and his fictional fiancée, Georg Bendemann and Frieda Brandenfeld, to Franz Kafka and Felice Bauer.[129] The story is often considered Kafka's breakthrough work. It deals with the troubled relationship of a son and his dominant father, facing a new situation after the son's engagement.[130][131] Kafka later described writing it as "a complete opening of body and soul",[132] a story that "evolved as a true birth, covered with filth and slime".[133] The story was first published in Leipzig in 1912 and dedicated "to Miss Felice Bauer", and in subsequent editions "for F."[74]

In 1912, Kafka wrote "Die Verwandlung" ("The Metamorphosis", or "The Transformation"),[134] published in 1915 in Leipzig. The story begins with a travelling salesman waking to find himself transformed into a ungeheures Ungeziefer, a monstrous vermin, Ungeziefer being a general term for unwanted and unclean animals. Critics regard the work as one of the seminal works of fiction of the 20th century.[135][136][137] The story "In der Strafkolonie" ("In the Penal Colony"), dealing with an elaborate torture and execution device, was written in October 1914,[74] revised in 1918, and published in Leipzig during October 1919. The story "Ein Hungerkünstler" ("A Hunger Artist"), published in the periodical Die neue Rundschau in 1924, describes a victimized protagonist who experiences a decline in the appreciation of his strange craft of starving himself for extended periods.[138] His last story, "Josefine, die Sängerin oder Das Volk der Mäuse" ("Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk"), also deals with the relationship between an artist and his audience.[139]

Novels

He began his first novel in 1912;[140] its first chapter is the story "Der Heizer" ("The Stoker"). Kafka called the work, which remained unfinished, Der Verschollene (The Man Who Disappeared or The Missing Man), but when Brod published it after Kafka's death he named it Amerika.[141] The inspiration for the novel was the time spent in the audience of Yiddish theatre the previous year, bringing him to a new awareness of his heritage, which led to the thought that an innate appreciation for one's heritage lives deep within each person.[142] More explicitly humorous and slightly more realistic than most of Kafka's works, the novel shares the motif of an oppressive and intangible system putting the protagonist repeatedly in bizarre situations.[143] It uses many details of experiences of his relatives who had emigrated to America[144] and is the only work for which Kafka considered an optimistic ending.[145]

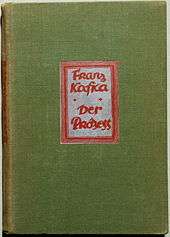

During 1914, Kafka began the novel Der Process (The Trial),[128] the story of a man arrested and prosecuted by a remote, inaccessible authority, with the nature of his crime revealed neither to him nor to the reader. Kafka did not complete the novel, although he finished the final chapter. According to Nobel Prize winner and Kafka scholar Elias Canetti, Felice is central to the plot of Der Process and Kafka said it was "her story".[146][147] Canetti titled his book on Kafka's letters to Felice Kafka's Other Trial, in recognition of the relationship between the letters and the novel.[147] Michiko Kakutani notes in a review for The New York Times that Kafka's letters have the "earmarks of his fiction: the same nervous attention to minute particulars; the same paranoid awareness of shifting balances of power; the same atmosphere of emotional suffocation—combined, surprisingly enough, with moments of boyish ardor and delight."[147]

According to his diary, Kafka was already planning his novel Das Schloss (The Castle), by 11 June 1914; however, he did not begin writing it until 27 January 1922.[128] The protagonist is the Landvermesser (land surveyor) named K., who struggles for unknown reasons to gain access to the mysterious authorities of a castle who govern the village. Kafka's intent was that the castle's authorities notify K. on his deathbed that his "legal claim to live in the village was not valid, yet, taking certain auxiliary circumstances into account, he was to be permitted to live and work there".[148] Dark and at times surreal, the novel is focused on alienation, bureaucracy, the seemingly endless frustrations of man's attempts to stand against the system, and the futile and hopeless pursuit of an unobtainable goal. Hartmut M. Rastalsky noted in his thesis: "Like dreams, his texts combine precise "realistic" detail with absurdity, careful observation and reasoning on the part of the protagonists with inexplicable obliviousness and carelessness."[149]

Publishing history

Kafka's stories were initially published in literary periodicals. His first eight were printed in 1908 in the first issue of the bi-monthly Hyperion.[150] Franz Blei published two dialogues in 1909 which became part of "Beschreibung eines Kampfes" ("Description of a Struggle").[150] A fragment of the story "Die Aeroplane in Brescia" ("The Aeroplanes at Brescia"), written on a trip to Italy with Brod, appeared in the daily Bohemia on 28 September 1909.[150][151] On 27 March 1910, several stories that later became part of the book Betrachtung were published in the Easter edition of Bohemia.[150][152] In Leipzig during 1913, Brod and publisher Kurt Wolff included "Das Urteil. Eine Geschichte von Franz Kafka." ("The Judgment. A Story by Franz Kafka.") in their literary yearbook for the art poetry Arkadia. The story "Vor dem Gesetz" ("Before the Law") was published in the 1915 New Year's edition of the independent Jewish weekly Selbstwehr; it was reprinted in 1919 as part of the story collection Ein Landarzt (A Country Doctor) and became part of the novel Der Process. Other stories were published in various publications, including Martin Buber's Der Jude, the paper Prager Tagblatt, and the periodicals Die neue Rundschau, Genius, and Prager Presse.[150]

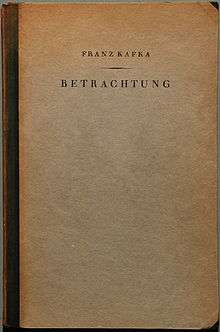

Kafka's first published book, Betrachtung (Contemplation, or Meditation), was a collection of 18 stories written between 1904 and 1912. On a summer trip to Weimar, Brod initiated a meeting between Kafka and Kurt Wolff;[153] Wolff published Betrachtung in the Rowohlt Verlag at the end of 1912 (with the year given as 1913).[154] Kafka dedicated it to Brod, "Für M.B.", and added in the personal copy given to his friend "So wie es hier schon gedruckt ist, für meinen liebsten Max—Franz K." ("As it is already printed here, for my dearest Max").[155]

Kafka's story "Die Verwandlung" ("The Metamorphosis") was first printed in the October 1915 issue of Die Weißen Blätter, a monthly edition of expressionist literature, edited by René Schickele.[154] Another story collection, Ein Landarzt (A Country Doctor), was published by Kurt Wolff in 1919,[154] dedicated to Kafka's father.[156] Kafka prepared a final collection of four stories for print, Ein Hungerkünstler (A Hunger Artist), which appeared in 1924 after his death, in Verlag Die Schmiede. On 20 April 1924, the Berliner Börsen-Courier published Kafka's essay on Adalbert Stifter.[157]

Max Brod

Kafka left his work, both published and unpublished, to his friend and literary executor Max Brod with explicit instructions that it should be destroyed on Kafka's death; Kafka wrote: "Dearest Max, my last request: Everything I leave behind me ... in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others'), sketches, and so on, [is] to be burned unread".[158][159] Brod ignored this request and published the novels and collected works between 1925 and 1935. He took many papers, which remain unpublished, with him in suitcases to Palestine when he fled there in 1939.[160] Kafka's last lover, Dora Diamant (later, Dymant-Lask), also ignored his wishes, secretly keeping 20 notebooks and 35 letters. These were confiscated by the Gestapo in 1933, but scholars continue to search for them.[161]

As Brod published the bulk of the writings in his possession,[162] Kafka's work began to attract wider attention and critical acclaim. Brod found it difficult to arrange Kafka's notebooks in chronological order. One problem was that Kafka often began writing in different parts of the book; sometimes in the middle, sometimes working backwards from the end.[163][164] Brod finished many of Kafka's incomplete works for publication. For example, Kafka left Der Process with unnumbered and incomplete chapters and Das Schloss with incomplete sentences and ambiguous content;[164] Brod rearranged chapters, copy edited the text, and changed the punctuation. Der Process appeared in 1925 in Verlag Die Schmiede. Kurt Wolff published two other novels, Das Schloss in 1926 and Amerika in 1927. In 1931, Brod edited a collection of prose and unpublished stories as Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer (The Great Wall of China), including the story of the same name. The book appeared in the Gustav Kiepenheuer Verlag. Brod's sets are usually called the "Definitive Editions".[165]

Modern editions

In 1961, Malcolm Pasley acquired most of Kafka's original handwritten work for the Oxford Bodleian Library.[166][167] The text for Der Process was later purchased through auction and is stored at the German Literary Archives in Marbach am Neckar, Germany.[167][168] Subsequently, Pasley headed a team (including Gerhard Neumann, Jost Schillemeit and Jürgen Born) which reconstructed the German novels; S. Fischer Verlag republished them.[169] Pasley was the editor for Das Schloss, published in 1982, and Der Process (The Trial), published in 1990. Jost Schillemeit was the editor of Der Verschollene (Amerika) published in 1983. These are called the "Critical Editions" or the "Fischer Editions".[170]

Unpublished papers

When Brod died in 1968, he left Kafka's unpublished papers, which are believed to number in the thousands, to his secretary Esther Hoffe.[171] She released or sold some, but left most to her daughters, Eva and Ruth, who also refused to release the papers. A court battle began in 2008 between the sisters and the National Library of Israel, which claimed these works became the property of the nation of Israel when Brod emigrated to British Palestine in 1939. Esther Hoffe sold the original manuscript of Der Process for US$2 million in 1988 to the German Literary Archive Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach am Neckar.[123][172] Only Eva was still alive as of 2012.[173] A ruling by a Tel Aviv family court in 2010 held that the papers must be released and a few were, including a previously unknown story, but the legal battle continued.[174] The Hoffes claim the papers are their personal property, while the National Library argues they are "cultural assets belonging to the Jewish people".[174] The National Library also suggests that Brod bequeathed the papers to them in his will. The Tel Aviv Family Court ruled in October 2012 that the papers were the property of the National Library.[175]

Critical interpretations

The poet W. H. Auden called Kafka "the Dante of the twentieth century";[176] the novelist Vladimir Nabokov placed him among the greatest writers of the 20th century.[177] Gabriel García Márquez noted the reading of Kafka's "The Metamorphosis" showed him "that it was possible to write in a different way".[108][178] A prominent theme of Kafka's work, first established in the short story "Das Urteil",[179] is father–son conflict: the guilt induced in the son is resolved through suffering and atonement.[16][179] Other prominent themes and archetypes include alienation, physical and psychological brutality, characters on a terrifying quest, and mystical transformation.[180]

Kafka's style has been compared to that of Kleist as early as 1916, in a review of "Die Verwandlung" and "Der Heizer" by Oscar Walzel in Berliner Beiträge.[181] The nature of Kafka's prose allows for varied interpretations and critics have placed his writing into a variety of literary schools.[105] Marxists, for example, have sharply disagreed over how to interpret Kafka's works.[99][105] Some accused him of distorting reality whereas others claimed he was critiquing capitalism.[105] The hopelessness and absurdity common to his works are seen as emblematic of existentialism.[182] Some of Kafka's books are influenced by the expressionist movement, though the majority of his literary output was associated with the experimental modernist genre. Kafka also touches on the theme of human conflict with bureaucracy. William Burroughs claims that such work is centred on the concepts of struggle, pain, solitude, and the need for relationships.[183] Others, such as Thomas Mann, see Kafka's work as allegorical: a quest, metaphysical in nature, for God.[184][185]

According to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, the themes of alienation and persecution, although present in Kafka's work, have been over-emphasised by critics. They argue Kafka's work is more deliberate and subversive—and more joyful—than may first appear. They point out that reading his work while focusing on the futility of his characters' struggles reveals Kafka's play of humour; he is not necessarily commenting on his own problems, but rather pointing out how people tend to invent problems. In his work, Kafka often created malevolent, absurd worlds.[186][187] Kafka read drafts of his works to his friends, typically concentrating on his humorous prose. The writer Milan Kundera suggests that Kafka's surrealist humour may have been an inversion of Dostoyevsky's presentation of characters who are punished for a crime. In Kafka's work a character is punished although a crime has not been committed. Kundera believes that Kafka's inspirations for his characteristic situations came both from growing up in a patriarchal family and living in a totalitarian state.[188]

Attempts have been made to identify the influence of Kafka's legal background and the role of law in his fiction.[189][190] Most interpretations identify aspects of law and legality as important in his work,[191] in which the legal system is often oppressive.[192] The law in Kafka's works, rather than being representative of any particular legal or political entity, is usually interpreted to represent a collection of anonymous, incomprehensible forces. These are hidden from the individual but control the lives of the people, who are innocent victims of systems beyond their control.[191] Critics who support this absurdist interpretation cite instances where Kafka describes himself in conflict with an absurd universe, such as the following entry from his diary:

Enclosed in my own four walls, I found myself as an immigrant imprisoned in a foreign country;... I saw my family as strange aliens whose foreign customs, rites, and very language defied comprehension;... though I did not want it, they forced me to participate in their bizarre rituals;... I could not resist.[193]

However, James Hawes argues many of Kafka's descriptions of the legal proceedings in Der Process—metaphysical, absurd, bewildering and nightmarish as they might appear—are based on accurate and informed descriptions of German and Austrian criminal proceedings of the time, which were inquisitorial rather than adversarial.[194] Although he worked in insurance, as a trained lawyer Kafka was "keenly aware of the legal debates of his day".[190][195] In an early 21st-century publication that uses Kafka's office writings as its point of departure,[196] Pothik Ghosh states that with Kafka, law "has no meaning outside its fact of being a pure force of domination and determination".[197]

Translations

The earliest English translations of Kafka's works were by Edwin and Willa Muir, who in 1930 translated the first German edition of Das Schloss. This was published as The Castle by Secker & Warburg in England and Alfred A. Knopf in the United States.[198] A 1941 edition, including a homage by Thomas Mann, spurred a surge in Kafka's popularity in the United States the late 1940s.[199] The Muirs translated all shorter works that Kafka had seen fit to print; they were published by Schocken Books in 1948 as The Penal Colony: Stories and Short Pieces,[200] including additionally The First Long Train Journey, written by Kafka and Brod, Kafka's "A Novel about Youth", a review of Felix Sternheim's Die Geschichte des jungen Oswald, his essay on Kleist's "Anecdotes", his review of the literary magazine Hyperion, and an epilogue by Brod.

Later editions, notably those of 1954 (Dearest Father. Stories and Other Writings), included text, translated by Eithne Wilkins and Ernst Kaiser,[201] which had been deleted by earlier publishers.[169] Known as "Definitive Editions", they include translations of The Trial, Definitive, The Castle, Definitive, and other writings. These translations are generally accepted to have a number of biases and are considered to be dated in interpretation.[202] Published in 1961 by Schocken Books, Parables and Paradoxes presented in a bilingual edition by Nahum N. Glatzer selected writings,[203] drawn from notebooks, diaries, letters, short fictional works and the novel Der Process.

New translations were completed and published based on the recompiled German text of Pasley and Schillemeit—The Castle, Critical by Mark Harman (Schocken Books, 1998),[167] The Trial, Critical by Breon Mitchell (Schocken Books, 1998),[204] and Amerika: The Man Who Disappeared by Michael Hofmann (New Directions Publishing, 2004).[205]

Translation problems to English

Kafka often made extensive use of a characteristic particular to the German language which permits long sentences that sometimes can span an entire page. Kafka's sentences then deliver an unexpected impact just before the full stop—this being the finalizing meaning and focus. This is due to the construction of subordinate clauses in German which require that the verb be positioned at the end of the sentence. Such constructions are difficult to duplicate in English, so it is up to the translator to provide the reader with the same (or at least equivalent) effect found in the original text.[206] German's more flexible word order and syntactical differences provide for multiple ways in which the same German writing can be translated into English.[207] An example is the first sentence of Kafka's "The Metamorphosis", which is crucial to the setting and understanding of the entire story:[208]

Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheuren Ungeziefer verwandelt. (original)As Gregor Samsa one morning from restless dreams awoke, found he himself in his bed into an enormous vermin transformed. (literal word-for-word translation)[209]

Another difficult problem facing translators is how to deal with the author's intentional use of ambiguous idioms and words that have several meanings which results in phrasing that is difficult to translate precisely.[210][211] One such instance is found in the first sentence of "The Metamorphosis". English translators often render the word Ungeziefer as "insect"; in Middle German, however, Ungeziefer literally means "an animal unclean for sacrifice";[212] in today's German it means vermin. It is sometimes used colloquially to mean "bug" —a very general term, unlike the scientific "insect". Kafka had no intention of labeling Gregor, the protagonist of the story, as any specific thing, but instead wanted to convey Gregor's disgust at his transformation.[135][136] Another example is Kafka's use of the German noun Verkehr in the final sentence of "Das Urteil". Literally, Verkehr means intercourse and, as in English, can have either a sexual or non-sexual meaning; in addition, it is used to mean transport or traffic. The sentence can be translated as: "At that moment an unending stream of traffic crossed over the bridge".[213] The double meaning of Verkehr is given added weight by Kafka's confession to Brod that when he wrote that final line, he was thinking of "a violent ejaculation".[133][214]

Legacy

Literary and cultural influence

Unlike many famous writers, Kafka is rarely quoted by others. Instead, he is noted more for his visions and perspective.[215] Shimon Sandbank, a professor, literary critic, and writer, identifies Kafka as having influenced Jorge Luis Borges, Albert Camus, Eugène Ionesco, J. M. Coetzee and Jean-Paul Sartre.[216] A Financial Times literary critic credits Kafka with influencing José Saramago,[217] and Al Silverman, a writer and editor, states that J. D. Salinger loved to read Kafka's works.[218] In 1999 a committee of 99 authors, scholars, and literary critics ranked Der Process and Das Schloss the second and ninth most significant German-language novels of the 20th century.[219] Sandbank argues that despite Kafka's pervasiveness, his enigmatic style has yet to be emulated.[216] Neil Christian Pages, a professor of German Studies and Comparative Literature at Binghamton University who specialises in Kafka's works, says Kafka's influence transcends literature and literary scholarship; it impacts visual arts, music, and popular culture.[220] Harry Steinhauer, a professor of German and Jewish literature, says that Kafka "has made a more powerful impact on literate society than any other writer of the twentieth century".[5] Brod said that the 20th century will one day be known as the "century of Kafka".[5]

Michel-André Bossy writes that Kafka created a rigidly inflexible and sterile bureaucratic universe. Kafka wrote in an aloof manner full of legal and scientific terms. Yet his serious universe also had insightful humour, all highlighting the "irrationality at the roots of a supposedly rational world".[180] His characters are trapped, confused, full of guilt, frustrated, and lacking understanding of their surreal world. Much of the post-Kafka fiction, especially science fiction, follow the themes and precepts of Kafka's universe. This can be seen in the works of authors such as George Orwell and Ray Bradbury.[180]

The following are examples of works across a range of literary, musical, and dramatic genres which demonstrate the extent of cultural influence:

| Title | Year | Medium | Remarks | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "A Friend of Kafka" | 1962 | short story | by Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer, about a Yiddish actor called Jacques Kohn who said he knew Franz Kafka; in this story, according to Jacques Kohn, Kafka believed in the Golem, a legendary creature from Jewish folklore | [221] |

| The Trial | 1962 | film | the film's director, Orson Welles, said, "Say what you like, but The Trial is my greatest work, even greater than Citizen Kane" | [222][223] |

| Watermelon Man | 1970 | film | partly inspired by "The Metamorphosis", where a white bigot wakes up as a black man | [224] |

| Klassenverhältnisse | 1984 | film | film adaptation of Amerika directed by Straub-Huillet | |

| "Kafka-Fragmente, Op. 24" | 1985 | music | by Hungarian composer György Kurtág for soprano and violin, using fragments of Kafka's diary and letters | [225] |

| Kafka's Dick | 1986 | play | by Alan Bennett, in which the ghosts of Kafka, his father Hermann and Brod arrive at the home of an English insurance clerk (and Kafka aficionado) and his wife | [226] |

| Kafka | 1991 | film | stars Jeremy Irons as the eponymous author; written by Lem Dobbs and directed by Steven Soderbergh, the movie mixes his life and fiction providing a semi-biographical presentation of Kafka's life and works; Kafka investigates the disappearance of one of his colleagues, taking Kafka through many of the writer's own works, most notably The Castle and The Trial | [227] |

| Franz Kafka's It's a Wonderful Life | 1993 | film | short comedy film made for BBC Scotland, won an Oscar, was written and directed by Peter Capaldi, and starred Richard E. Grant as Kafka | [228] |

| "Bad Mojo" | 1996 | computer game | loosely based on "The Metamorphosis", with characters named Franz and Roger Samms, alluding to Gregor Samsa | [229] |

| In the Penal Colony | 2000 | opera | by Philip Glass | [230] |

| Kafka on the Shore | 2002 | novel | by Japanese writer Haruki Murakami, on The New York Times 10 Best Books of 2005 list, World Fantasy Award recipient | [231] |

| Kafka's Trial | 2005 | opera | by Danish composer Poul Ruders, based on the novel and parts of Kafka's life; first performed in 2005, released on CD | [232] |

| Kafka's Soup | 2005 | book | by Mark Crick, is a literary pastiche in the form of a cookbook, with recipes written in the style of a famous author | [233] |

| Introducing Kafka | 2007 | graphic novel | by Robert Crumb and David Zane Mairowitz, contains text and illustrations introducing Kafka's life and work | |

| "Kafkaesque" | 2010 | TV series | Breaking Bad Season 3 episode written by Peter Gould & George Mastras. Jesse Pinkman, at a group therapy meeting, describes his new workplace as a dreary, "totally corporate" laundromat mired in bureaucracy. He complains about his boss and that he's not worthy to meet the owner, whom everyone fears. "Sounds kind of Kafkaesque," responds the group leader. | |

| "Kafka the Musical" | 2011 | radio play | by BBC Radio 3 produced as part of their Play of the Week programme. Franz Kafka was played by David Tennant | [234] |

| "Sound Interpretations – Dedication To Franz Kafka" | 2012 | music | HAZE Netlabel released musical compilation Sound Interpretations — Dedication To Franz Kafka. In this release musicians rethink the literary heritage of Kafka | [235] |

| Google Doodle | 2013 | internet culture | Google had a sepia-toned doodle of a roach in a hat opening a door, honoring Kafka's 130th birthday | [236] |

| The Metamorphosis | 2013 | dance | Royal Ballet production of The Metamorphosis with Edward Watson | [237] |

| Café Kafka | 2014 | opera | by Spanish composer Francisco Coll on a text by Meredith Oakes, built from texts and fragments by Franz Kafka; Commissioned by Aldeburgh Music, Opera North and Royal Opera Covent Garden | [238] |

"Kafkaesque"

Kafka's writing has inspired the term "Kafkaesque", used to describe concepts and situations reminiscent of his work, particularly Der Process (The Trial) and "Die Verwandlung" (The Metamorphosis). Examples include instances in which bureaucracies overpower people, often in a surreal, nightmarish milieu which evokes feelings of senselessness, disorientation, and helplessness. Characters in a Kafkaesque setting often lack a clear course of action to escape a labyrinthine situation. Kafkaesque elements often appear in existential works, but the term has transcended the literary realm to apply to real-life occurrences and situations that are incomprehensibly complex, bizarre, or illogical.[5][222][239][240]

Numerous films and television works have been described as Kafkaesque, and the style is particularly prominent in dystopian science fiction. Works in this genre that have been thus described include Patrick Bokanowski's 1982 film The Angel, Terry Gilliam's 1985 film Brazil, and the 1998 science fiction film noir, Dark City. Films from other genres which have been similarly described include The Tenant (1976) and Barton Fink (1991).[241] The television series The Prisoner and The Twilight Zone are also frequently described as Kafkaesque.[242][243]

However, with common usage, the term has become so ubiquitous that Kafka scholars note it's often misused.[244] More accurately then, according to author Ben Marcus, paraphrased in "What it Means to be Kafkaesque" by Joe Fassler in The Atlantic, "Kafka’s quintessential qualities are affecting use of language, a setting that straddles fantasy and reality, and a sense of striving even in the face of bleakness—hopelessly and full of hope." [245]

Commemoration

The Franz Kafka Museum in Prague is dedicated to Kafka and his work. A major component of the museum is an exhibit The City of K. Franz Kafka and Prague, which was first shown in Barcelona in 1999, moved to the Jewish Museum in New York City, and was finally established in 2005 in Prague in Malá Strana (Lesser Town), along the Moldau. The museum calls its display of original photos and documents Město K. Franz Kafka a Praha (City K. Kafka and Prague) and aims to immerse the visitor into the world in which Kafka lived and about which he wrote.[246]

The Franz Kafka Prize is an annual literary award of the Franz Kafka Society and the City of Prague established in 2001. It recognizes the merits of literature as "humanistic character and contribution to cultural, national, language and religious tolerance, its existential, timeless character, its generally human validity, and its ability to hand over a testimony about our times".[247] The selection committee and recipients come from all over the world, but are limited to living authors who have had at least one work published in the Czech language.[247] The recipient receives $10,000, a diploma, and a bronze statuette at a presentation in Prague's Old Town Hall on the Czech State Holiday in late October.[247]

San Diego State University (SDSU) operates the Kafka Project, which began in 1998 as the official international search for Kafka's last writings.[161]

See also

- 3412 Kafka, an asteroid

- Oskar Pollak

Notes

- ↑ German pronunciation: [fʁant͡s ˈkafkaː]; Czech pronunciation: [ˈfrant͡s ˈkafka]; in Czech he was sometimes called František Kafka (Czech pronunciation: [ˈfrancɪʃɛk ˈkafka]); English pronunciation: /ˈkɑːfkɑː, -kə/ (Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary: "Kafka").

- ↑ Some sources list June (Murray) as Kafka's graduation month and some list July (Brod).[37][38]

- ↑ "Kampf" also translates to "fight".

References

Citations

- 1 2 Koelb 2010, p. 12.

- ↑ Czech Embassy 2012.

- ↑ Spindler, William (1993). "Magical Realism: A Typology" (PDF). Forum for Modern Language Studies. XXIX (1): 90–93. doi:10.1093/fmls/XXIX.1.75. (subscription required)

- ↑ "Franz Kafka". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Steinhauer 1983, pp. 390–408.

- 1 2 Gilman 2005, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Northey 1997, pp. 8–10.

- ↑ Kohoutikriz 2011.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Northey 1997, p. 92.

- ↑ Gray 2005, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Hamalian 1974, p. 3.

- ↑ Corngold 1972, pp. xii, 11.

- 1 2 Kafka-Franz, Father 2012.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 9.

- 1 2 Brod 1960, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 15, 17, 22–23.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 390–391, 462–463.

- ↑ Stach 2005, p. 13.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 Hawes 2008, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 Sayer 1996, pp. 164–210.

- ↑ Kempf 2005, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Corngold 2004, p. xii.

- ↑ Diamant 2003, pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 40–41.

- 1 2 Gray 2005, p. 179.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 43–70.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 40.

- 1 2 Brod 1960, p. 14.

- ↑ Brod 1966, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Stach 2005, p. 362.

- ↑ Gray 2005, pp. 74, 273.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 51, 122–124.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 80–83.

- ↑ Murray 2004, p. 62.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 78.

- ↑ Karl 1991, p. 210.

- ↑ Glen 2007, pp. 23–66.

- ↑ Drucker 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ Corngold et al. 2009, pp. 250–254.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 26–30.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 81–84.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 23–25.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Spector 2000, p. 17.

- ↑ Keren 1993, p. 3.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 34–39.

- ↑ Koelb 2010, p. 32.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 29, 73–75, 109–110, 206.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 154.

- ↑ Corngold 2011, pp. 339–343.

- 1 2 Hawes 2008, p. 186.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 44, 207.

- ↑ Hawes 2008, pp. 186, 191.

- 1 2 European Graduate School 2012.

- ↑ Stach 2005, p. 43.

- 1 2 Banville 2011.

- ↑ Köhler 2012.

- 1 2 3 Stach 2005, p. 1.

- ↑ Seubert 2012.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 196–197.

- ↑ Hawes 2008, pp. 129, 198–199.

- ↑ Murray 2004, pp. 276–279.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 379–389.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 240–242.

- ↑ S. Fischer 2012.

- ↑ Alt 2005, p. 303.

- ↑ Hawes 2008, pp. 180–181.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 1, 379–389, 434–436.

- ↑ Apel 2012, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brod 1966, p. 389.

- ↑ Hempel 2002.

- ↑ Janouch 1971, pp. 14, 17.

- 1 2 Fichter 1987, pp. 367–377.

- ↑ Repertory 2005.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 41.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 42.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 Brod 1966, p. 49.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 47.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 52.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 90.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 92.

- 1 2 Brod 1960, p. 214.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 156.

- ↑ Pérez-Álvarez 2003, pp. 181–194.

- ↑ Miller 1984, pp. 242–306.

- ↑ McElroy 1985, pp. 217–232.

- ↑ Project Gutenberg 2012.

- ↑ Gray 1973, p. 196.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Fichter 1988, pp. 231–238.

- ↑ Gilman 1995, back cover.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 128.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 86.

- 1 2 Lib.com 2008.

- ↑ Bergman 1969, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Bruce 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ Preece 2001, p. 131.

- ↑ Hughes 1986, pp. 248–249.

- ↑ Bathrick 1995, pp. 67–70.

- 1 2 3 4 Socialist Worker 2007.

- ↑ History Guide 2006.

- 1 2 3 Haaretz 2008.

- 1 2 Kafka-Franz 2012.

- ↑ Gilman 2005, p. 31.

- ↑ Connolly 2008.

- ↑ Harper's 2008.

- ↑ Hawes 2008, pp. 119–126.

- ↑ Bloom 1994, p. 428.

- ↑ Kahn & Hook 1993, p. 191.

- 1 2 3 Rothkirchen 2005, p. 23.

- ↑ Tal, Josef. Tonspur – Auf Der Suche Nach Dem Klang Des Lebens. Berlin: Henschel, 2005. pp. 43–44

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 196.

- ↑ Bloom 2011.

- ↑ Believer 2006.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 209–211.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 211.

- ↑ F. Kafka, New Jewish Cemetery, Prague: Marsyas 1991, p.56

- 1 2 New York Times 2010.

- ↑ Stach 2005, p. 2.

- ↑ Murray 2004, pp. 367.

- ↑ Furst 1992, p. 84.

- ↑ Pawel 1985, pp. 160–163.

- 1 2 3 Brod 1966, p. 388.

- ↑ Brod 1966114f

- ↑ Ernst 2010.

- ↑ Hawes 2008, pp. 159, 192.

- ↑ Stach 2005, p. 113.

- 1 2 Brod 1960, p. 129.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 113.

- 1 2 Sokel 1956, pp. 203–214.

- 1 2 Luke 1951, pp. 232–245.

- ↑ Dodd 1994, pp. 165–168.

- ↑ Gray 2005, p. 131.

- ↑ Horstkotte 2009.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 113.

- ↑ Brod 1960, pp. 128, 135, 218.

- ↑ Koelb 2010, p. 34.

- ↑ Sussman 1979, pp. 72–94.

- ↑ Stach 2005, p. 79.

- ↑ Brod 1960, p. 137.

- ↑ Stach 2005, pp. 108–115, 147, 139, 232.

- 1 2 3 Kakutani 1988.

- ↑ Boyd 2004, p. 139.

- ↑ Rastalsky 1997, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Itk 2008.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 94.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 61.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 110.

- 1 2 3 European Graduate School, Articles 2012.

- ↑ Brod 1966, p. 115.

- ↑ Leiter 1958, pp. 337–347.

- ↑ Krolop 1994, p. 103.

- ↑ Kafka 1988, publisher's notes.

- ↑ McCarthy 2009.

- ↑ Butler 2011, pp. 3–8.

- 1 2 Kafka Project SDSU 2012.

- ↑ Contijoch 2000.

- ↑ Kafka 2009, p. xxvii.

- 1 2 Diamant 2003, p. 144.

- ↑ Classe 2000, p. 749.

- ↑ Jewish Heritage 2012.

- 1 2 3 Kafka 1998, publisher's notes.

- ↑ O'Neill 2004, p. 681.

- 1 2 Adler 1995.

- ↑ Oxford Kafka Research Centre 2012.

- ↑ Guardian 2010.

- ↑ Buehrer 2011.

- ↑ NPR 2012.

- 1 2 Lerman 2010.

- ↑ Rudoren & Noveck 2012.

- ↑ Bloom 2002, p. 206.

- ↑ Durantaye 2007, pp. 315–317.

- ↑ Paris Review 2012.

- 1 2 Gale Research Inc. 1979, pp. 288–311.

- 1 2 3 Bossy 2001, p. 100.

- ↑ Furst 1992, p. 83.

- ↑ Sokel 2001, pp. 102–109.

- ↑ Burrows 2011.

- ↑ Panichas 2004, pp. 83–107.

- ↑ Gray 1973, p. 3.

- ↑ Kavanagh 1972, pp. 242–253.

- ↑ Rahn 2011.

- ↑ Kundera 1988, pp. 82–99.

- ↑ Glen 2007.

- 1 2 Banakar 2010.

- 1 2 Glen 2011, pp. 47–94.

- ↑ Hawes 2008, pp. 216–218.

- ↑ Preece 2001, pp. 15–31.

- ↑ Hawes 2008, pp. 212–214.

- ↑ Ziolkowski 2003, p. 224.

- ↑ Corngold et al. 2009, pp. xi, 169, 188, 388.

- ↑ Ghosh 2009.

- ↑ Guardian 1930.

- ↑ Koelb 2010, p. 69.

- ↑ Kafka 1948, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Kafka 1954, publisher's notes.

- ↑ Sokel 2001, p. 63.

- ↑ Preece 2001, p. 167.

- ↑ Preece 2001, pp. xv, 225.

- ↑ Kirsch 2009.

- ↑ Kafka 1996, p. xi.

- ↑ Newmark 1991, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Bloom 2003, pp. 23–26.

- ↑ Prinsky 2002.

- ↑ Lawson 1960, pp. 216–219.

- ↑ Rhine 1989, pp. 447–458.

- ↑ Corngold 1973, p. 10.

- ↑ Kafka 1996, p. 75.

- ↑ Hawes 2008, p. 50.

- ↑ Hawes 2008, p. 4.

- 1 2 Sandbank 1992, pp. 441–443.

- ↑ Financial Times 2009.

- ↑ Silverman 1986, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ LiteraturHaus 1999.

- ↑ Coker 2012.

- ↑ Singer 1970, p. 311.

- 1 2 Adams 2002, pp. 140–157.

- ↑ Welles Net 1962.

- ↑ Elsaesser 2004, p. 117.

- ↑ Opera Today 2010.

- ↑ Times Literary Supplement 2005.

- ↑ Writer's Institute 1992.

- ↑ New York Times 1993.

- ↑ Dembo 1996, p. 106.

- ↑ Glass 2001.

- ↑ Updike 2005.

- ↑ Ruders 2005.

- ↑ Milner 2005.

- ↑ BBC 2012.

- ↑ HAZE 2012.

- ↑ Bury 2013.

- ↑ Rizzulo 2013.

- ↑ Jeal 2014.

- ↑ Aizenberg 1986, pp. 11–19.

- ↑ Strelka 1984, pp. 434–444.

- ↑ Palmer 2004, pp. 159–192.

- ↑ O'Connor 1987.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times 2009.

- ↑ "The Essence of 'Kafkaesque'". The New York Times. 29 December 1991.

- ↑ Fassler, Joe. "What It Really Means to Be 'Kafkaesque'".

- ↑ Kafka Museum 2005.

- 1 2 3 Kafka Society 2011.

Bibliography

- Alt, Peter-André (2005). Franz Kafka: Der ewige Sohn. Eine Biographie (in German). München: Verlag C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-53441-6.

- Bathrick, David (1995). The Powers of Speech: The Politics of Culture in the GDR. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Bergman, Hugo (1969). Memories of Franz Kafka in Franz Kafka Exhibition (Catalogue) (PDF). Library: The Jewish National and University Library. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- Bloom, Harold (2003). Franz Kafka. Bloom's Major Short Story Writers. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7910-6822-9.

- Bloom, Harold (Spring 2011). "Franz Kafka's Zionism". Midstream. 57 (2).

- Bloom, Harold (2002). Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Creative Minds. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-52717-0.

- Bloom, Harold (1994). The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. New York: Riverhead Books, Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-57322-514-4.

- Bossy, Michel-André (2001). Artists, Writers, and Musicians: An Encyclopedia of People Who Changed the World. Westport, Connecticut: Oryx Press. ISBN 978-1-57356-154-9.

- Boyd, Ian R. (2004). Dogmatics Among the Ruins: German Expressionism and the Enlightenment. Bern: Peter Lang AG. ISBN 978-3-03910-147-4.

- Brod, Max (1966). Über Franz Kafka (in German). Hamburg: S. Fischer Verlag.

- Bruce, Iris (2007). Kafka and Cultural Zionism — Dates in Palestine. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-22190-4.

- Classe, Olive (2000). Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English, Vol. 1. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 978-1-884964-36-7.

- Contijoch, Francesc Miralles (2000). Franz Kafka (in Spanish). Barcelona: Oceano Grupo Editorial, S.A. ISBN 978-84-494-1811-2.

- Corngold, Stanley (1972). Introduction to The Metamorphosis. New York: Bantam Classics. ISBN 978-0-553-21369-0.

- Corngold, Stanley (1973). The Commentator's Despair. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0-8046-9017-1.

- Corngold, Stanley (2004). Lambent Traces: Franz Kafka. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11816-1.

- Corngold, Stanley (2009). Franz Kafka: The Office Writings. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12680-7.

- Diamant, Kathi (2003). Kafka's Last Love: The Mystery of Dora Diamant. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01551-1.

- Drucker, Peter (2002). Managing in the Next Society (2007 ed.). Oxford: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7506-8505-4.

- Engel, Manfred; Auerochs, Bernd (2010). Kafka-Handbuch. Leben – Werk – Wirkung (in German). Metzler: Stuttgart, Weimar. ISBN 978-3-476-02167-0.

- Elsaesser, Thomas (2004). The Last Great American Picture Show. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-493-6.

- Furst, Lillian R. (1992). Through the Lens of the Reader: Explorations of European Narrative. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0808-7. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- Gale Research Inc. (1979). Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism: Excerpts from Criticism of the Works of Novelists, Poets, Playwrights, Short Story Writers, & Other Creative Writers Who Died Between 1900 & 1999. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-8103-0176-4.

- Gilman, Sander (1995). Franz Kafka, the Jewish Patient. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-91391-1.

- Gilman, Sander (2005). Franz Kafka. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-881872-64-1.

- Gray, Richard T. (2005). A Franz Kafka Encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30375-3.

- Gray, Ronald (1973). Franz Kafka. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20007-3.

- Hamalian, Leo (1974). Franz Kafka: A Collection of Criticism. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-025702-3.

- Hawes, James (2008). Why You Should Read Kafka Before You Waste Your Life. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-37651-2.

- Janouch, Gustav (1971). Conversations with Kafka (2 ed.). New York: New Directions Books. ISBN 978-0-8112-0071-4. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- Kafka, Franz (1948). The Penal Colony: Stories and Short Pieces (1987 ed.). New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-3198-4.

- Kafka, Franz (1954). Dearest Father. Stories and Other Writings. New York: Schocken Books.

- Kafka, Franz (1988). The Castle. New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-0872-6.

- Kafka, Franz (1996). The Metamorphosis and Other Stories. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-56619-969-8.

- Kafka, Franz (1998). The Trial. New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-0999-0.

- Kafka, Franz (2009). The Trial. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923829-3.

- Kahn, Lothar; Hook, Donald D. (1993). Between Two Worlds: a cultural history of German-Jewish writers. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8138-1233-5.

- Karl, Frederick R. (1991). Franz Kafka: Representative Man. Boston: Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 978-0-395-56143-0.

- Koelb, Clayton (2010). Kafka: A Guide for the Perplexed. Chippenham, Wiltshire: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-9579-2.

- Krolop, Kurt (1994). Kafka und Prag (in German). Prague: Goethe-Institut. ISBN 978-3-11-014062-0.

- Miller, Alice (1984). Thou Shalt Not Be Aware:Society's Betrayal of the Child. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux. ISBN 978-0-9567982-1-3.

- Murray, Nicholas (2004). Kafka. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10631-2.

- Newmark, Peter (1991). About Translation. Wiltshire, England: Cromwell Press. ISBN 978-1-85359-117-4.

- Northey, Anthony (1997). Mišpoche Franze Kafky (in Czech). Prague: Nakladatelství Primus. ISBN 978-80-85625-45-5.

- O'Neill, Patrick M. (2004). Great World Writers: Twentieth Century. Tarrytown, New York: Marshal Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-7477-7.

- Pawel, Ernst (1985). The Nightmare of Reason: A Life of Franz Kafka. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-374-52335-0.

- Preece, Julian (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Kafka. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66391-5.

- Rothkirchen, Livia (2005). The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia: facing the Holocaust. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3952-4.

- Silverman, Al, ed. (1986). The Book of the Month: Sixty Years of Books in American Life. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-10119-2.

- Singer, Isaac Bashevis (1970). A Friend of Kafka, and Other Stories. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-15880-4.

- Sokel, Walter H. (2001). The Myth of Power and the Self: Essays on Franz Kafka. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2608-4.

- Spector, Scott (2000). Prague Territories: National Conflict and Cultural Innovation in Franz Kafka's Fin de Siècle. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23692-9.

- Stach, Reiner (2005). Kafka: The Decisive Years. New York: Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-100752-3.

- Sussman, Henry (1979). Franz Kafka: Geometrician of Metaphor. Madison, Wisconsin: Coda Press. ISBN 978-0-930956-02-8.

- Ziolkowski, Theodore (2003). The Mirror of Justice: Literary Reflections of Legal Crisis. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11470-5.

Journals

- Adams, Jeffrey (Summer 2002). "Orson Welles's "The Trial:" Film Noir and the Kafkaesque". College Literature, Literature and the Visual Arts. West Chester, Pennsylvania. 29 (3). JSTOR 25112662.

- Aizenberg, Edna (July–December 1986). "Kafkaesque Strategy and Anti-Peronist Ideology Martinez Estrada's Stories as Socially Symbolic Acts". Latin American Literary Review. Chicago. 14 (28). JSTOR 20119426.

- Banakar, Reza (Fall 2010). "In Search of Heimat: A Note on Franz Kafka's Concept of Law". Law and Literature. Berkeley, California. 22 (2). doi:10.2139/ssrn.1574870. SSRN 1574870

.

.

- Butler, Judith (3 March 2011). "Who Owns Kafka". London Review of Books. London. 33 (5). Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Corngold, Stanley (Fall 2011). "Kafkas Spätstil/Kafka's Late Style: Introduction". Monatshefte. Madison, Wisconsin. 103 (3). doi:10.1353/mon.2011.0069.

- Dembo, Arinn (June 1996). "Twilight of the Cockroaches: Bad Mojo Evokes Kafka So Well It'll Turn Your Stomach". Computer Gaming World. New York (143).

- Dodd, W. J. (1994). "Kafka and Dostoyevsky: The Shaping of Influence". Comparative Literature Studies. State College, Pennsylvania. 31 (2). JSTOR 40246931.

- Durantaye, Leland de la (2007). "Kafka's Reality and Nabokov's Fantasy: On Dwarves, Saints, Beetles, Symbolism and Genius" (PDF). Comparative Literature. 59 (4): 315. doi:10.1215/-59-4-315.http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic772297.files/Kafka%20and%20Nabokov.pdf

- Fichter, Manfred M. (May 1987). "The Anorexia Nervosa of Franz Kafka". International Journal of Eating Disorders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. 6 (3): 367. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198705)6:3<367::AID-EAT2260060306>3.0.CO;2-W.

- Fichter, Manfred M. (July 1988). "Franz Kafka's anorexia nervosa". Fortschritte der Neurologie · Psychiatrie (in German). Munich: Psychiatrische Klinik der Universität München. 56 (7): 231–8. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1001787. PMID 3061914.

- Fort, Jeff (March 2006). "The Man Who Could Not Disappear". The Believer. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- Glen, Patrick J. (2007). "The Deconstruction and Reification of Law in Franz Kafka's Before the Law and The Trial" (PDF). Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal. Los Angeles: University of Southern California. 17 (23). Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Glen, Patrick J. (2011). "Franz Kafka, Lawrence Joseph, and the Possibilities of Jurisprudential Literature" (PDF). Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal. Los Angeles: University of Southern California. 21 (47). Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Horton, Scott (19 August 2008). "In Pursuit of Kafka's Porn Cache: Six questions for James Hawes". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Hughes, Kenneth (Summer 1986). "Franz Kafka: An Anthology of Marxist Criticism". Monatshefte. Madison, Wisconsin. 78 (2). JSTOR 30159253.

- Kavanagh, Thomas M. (Spring 1972). "Kafka's "The Trial": The Semiotics of the Absurd". Novel: A Forum on Fiction. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. 5 (3). doi:10.2307/1345282. JSTOR 1345282.

- Kempf, Franz R. (Summer 2005). "Franz Kafkas Sprachen: "... in einem Stockwerk des innern babylonischen Turmes. .."". Shofar: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. 23 (4): 159. doi:10.1353/sho.2005.0155.

- Keren, Michael (1993). "The 'Prague Circle' and the Challenge of Nationalism". History of European Ideas. Oxford: Pergamon Press. 16 (1–3): 3. doi:10.1016/S0191-6599(05)80096-8.

- Kundera, Milan (Winter 1988). "Kafka's World". The Wilson Quarterly. Washington, D.C.: The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 12 (5). JSTOR 40257735.

- Lawson, Richard H. (May 1960). "Ungeheueres Ungeziefer in Kafka's "Die Verwandlung"". The German Quarterly. Cherry Hill, New Jersey: American Association of Teachers of German. 33 (3). JSTOR 402242.

- Leiter, Louis H. (1958). "A Problem in Analysis: Franz Kafka's 'A Country Doctor'". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Philadelphia: American Society for Aesthetics. 16 (3). doi:10.2307/427381.

- Luke, F. D. (April 1951). "Kafka's "Die Verwandlung"". The Modern Language Review. Cambridge. 46 (2). doi:10.2307/3718565. JSTOR 3718565.

- McElroy, Bernard (Summer 1985). "The Art of Projective Thinking: Franz Kafka and the Paranoid Vision". Modern Fiction Studies. Cambridge. 31 (2): 217. doi:10.1353/mfs.0.0042.

- Panichas, George A. (Spring–Fall 2004). "Kafka's Afflicted Vision: A Literary-Theological Critique". Humanitas. Bowie, Maryland: National Humanities Institute. 17 (1–2).

- Pérez-Álvarez, Marino (2003). "The Schizoid Personality of Our Time". International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. Almería, Spain. 3 (2).

- Rhine, Marjorie E. (Winter 1989). "Untangling Kafka's Knotty Texts: The Translator's Prerogative?". Monatshefte. Madison, Wisconsin. 81 (4). JSTOR 30166262.

- Sayer, Derek (1996). "The Language of Nationality and the Nationality of Language: Prague 1780–1920 – Czech Republic History". Past and Present. Oxford. 153 (1): 164. doi:10.1093/past/153.1.164. OCLC 394557.

- Sandbank, Shimon (1992). "After Kafka: The Influence of Kafka's Fiction". Penn State University Press. Oxford. 29 (4). JSTOR 40246852.

- Sokel, Walter H. (April–May 1956). "Kafka's "Metamorphosis": Rebellion and Punishment". Monatshefte. Madison, Wisconsin. 48 (4). JSTOR 30166165.

- Steinhauer, Harry (Autumn 1983). "Franz Kafka: A World Built on a Lie". The Antioch Review. Yellow Springs, Ohio. 41 (4): 390. doi:10.2307/4611280. JSTOR 4611280.

- Strelka, Joseph P. (Winter 1984). "Kafkaesque Elements in Kafka's Novels and in Contemporary Narrative Prose". Comparative Literature Studies. State College, Pennsylvania. 21 (4). JSTOR 40246504.

- Updike, John (24 January 2005). "Subconscious Tunnels: Haruki Murakami's dreamlike new novel". The New Yorker. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

Newspapers

- Adler, Jeremy (13 October 1995). "Stepping into Kafka's Head". New York Times Literary Supplement. Retrieved 4 August 2012. (subscription required)

- Apel, Friedman (28 August 2012). "Der Weg in die Ewigkeit führt abwärts / Roland Reuß kramt in Kafkas Zürauer Zetteln". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German).

- Banville, John (14 January 2011). "Franz Kafka's other trial / An allegory of the fallen man's predicament, or an expression of guilt at a tormented love affair?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Batuman, Elif (22 September 2010). "Kafka's Last Trial". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Buehrer, Jack (9 March 2011). "Battle for Kafka legacy drags on". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on 2011-06-15. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- Burrows, William (22 December 2011). "Winter read: The Castle by Franz Kafka". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Connolly, Kate (14 August 2008). "Porn claims outrage German Kafka scholars". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Glass, Philip (10 June 2001). "Adapting the Horrors of a Kafka Story To Suit Glass's Music". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Jeal, Erica (18 March 2014). "The Commission/Café Kafka, Royal Opera/Opera North/Aldeburgh Music – review". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- Kakutani, Michiko (2 April 1988). "Books of the Times; Kafka's Kafkaesque Love Letters". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- Kenley-Letts, Ruth (1993). "Franz Kafka's "It's a Wonderful Life" (1993)". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- Kirsch, Adam (2 January 2009). "America, 'Amerika'". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- Lerman, Antony (22 July 2010). "The Kafka legacy: who owns Jewish heritage?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- McCarthy, Rory (24 October 2009). "Israel's National Library adds a final twist to Franz Kafka's Trial". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- McLellan, Dennis (15 January 2009). "Patrick McGoohan dies at 80; TV's 'Secret Agent' and 'Prisoner'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Metcalfe, Anna (5 December 2009). "Small Talk: José Saramago". Financial Times. Retrieved 1 August 2012. (subscription required)