Kwan Um School of Zen

| The Kwan Um School of Zen | |

|---|---|

| |

| School: | Korean Seon |

| Founder: | Seungsahn |

| Founded: | 1983 |

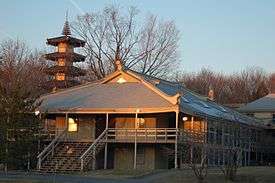

| Head temple: | Providence Zen Center |

| Guiding teacher: | Soenghyang |

| Head teacher (Europe): | Wubong |

| Head abbot: | Daekwang |

| Lineage: | Seung Sahn |

| Primary location: | International |

| Website | |

| www.kwanumzen.org/ http://zen.kwanumeurope.org/ | |

The Kwan Um School of Zen (관음선종회) (KUSZ) is an international school of zen centers and groups founded in 1983 by Seungsahn. The school's international head temple is located at the Providence Zen Center in Cumberland, Rhode Island, which was founded in 1972 shortly after Seungsahn first came to the United States (then in Providence). The Kwan Um style of Buddhist practice combines ritual common both to Korean Buddhism as well as Rinzai school of Zen, and their morning and evening services include elements of Huayan and Pure Land Buddhism. While the Kwan Um Zen School comes under the banner of the Jogye Order of Korean Seon, the school has been adapted by Seungsahn to the needs of Westerners. According to James Ishmael Ford, the Kwan Um School of Zen is the largest Zen school in the Western world.

History

.jpg)

Seungsahn first arrived in the United States in 1972, where he lived in Providence, Rhode Island and worked at a Korean-owned laundromat.[1] Not long after, students from nearby Brown University began coming to him for instruction. This resulted in the opening of the Providence Zen Center in 1972. At the time of his arrival in America, Seungsahn's teachings were different from many of his Japanese predecessors who had taught Zen to Americans. During the early days he did not place a strong emphasis on zazen, which is the core of most Japanese traditions of Zen. It was through the urging of some of his first students, some who had practiced in Japanese schools previously, that Seungsahn came to place a stronger emphasis on sitting meditation.[2]

In 1974 Seungsahn began founding more zen centers in the United States—his school still yet to be established—beginning with Dharma Zen Center in Los Angeles,[3] a place where laypeople and the ordained could practice and live together. That following year he went on to found the Chogye International Zen Center of New York City, and then in 1977 Empty Gate Zen Center.[4] Meanwhile, in 1979, the Providence Zen Center moved from its location in Providence to its current space in Cumberland, Rhode Island.[5][6] The Kwan Um School of Zen was founded in 1983 and—unlike more traditional practice in Korea—Seungsahn allowed the laity in the lineage to wear the robe of a Buddhist monk. Celibacy was not required, and the rituals of the school are unique. Although the Kwan Um School does utilize traditional Seon, Chan and Zen ritual, elements of their practice also closely resemble rituals found often in Pure Land and Huayan traditions.[7] In 1986, along with a former student and Dharma heir Dae Gak, Seungsahn founded a retreat center in Clay City, Kentucky called Furnace Mountain—the temple name being Kwan Se Um San Ji Sah (or, Perceive World Sound High Ground Temple). The center functions independent of the Kwan Um organization today.[8]

In Somerset West of South Africa, the Kwan Um School of Zen once had the largest following of Zen practitioners in the area with their former Dharma Centre[9] (though today the center acts independent of the Kwan Um organization). Founded in 1982 by Heila Downey (a former student of Philip Kapleau), the center had for many years acted as an informal affiliate of the Rochester Zen Center in Rochester, New York. In 1989 Dharma Centre began embracing the practices of the Kwan um School of Zen. Heila Downey herself was made a Ji Do Poep Sa Nim, granting her inka, authority to teach within the Kwan Um School of Zen.[10] According to Michel Clasquin in the book Westward Dharma: Buddhism Beyond Asia, "There are other Zen groups in South Africa, notably in Johannesburg, but the Dharma Centre, now headquartered in the town of Robertson, is clearly the leading Zen-based organization. The institutional support it receives from the Kwan Um organization means that it is able to import teachers with relative ease. However, it should be noted that in a suburban satellite center in Cape Town, the Dharma Centre has been forced by popular demand to reinstitute a weekly meditation session shorn of all ritual, much as things were before 1989."[10] According to the Dharma Centre's own website, "With changing times, our practice and teaching has evolved to express a style in harmony with our African heritage resulting in our resignation from the Kwan Um School of Zen." Regardless of this resignation, the center does demonstrate a continuing respect for the teachings of Seungsahn by stating, "As the African Dharma continues to develop and grow, Zen Master Seung Sahn's legacy and teaching will continue to sustain and encourage us in the never-ending quest of 'Who am I' and 'How May I Help You?'"[9]

The Kwan Um School of Zen also has one of only a few Zen centers located in Israel with their Tel Aviv Zen Center, led by Revital Dan. It is one of only four Kwan Um School Zen centers in Israel, with its history linked to trips by Seungsahn to Israel in the 1990s to teach at various alternative medicine centers. According to Lionel Obadia, "Revital Dan, currently heading the TAZC, followed [Seungsahn] back to Korea and trained in the monastic style of retreat. Back in Israel with her Dharma-teacher degree, she founded a Zen group. The opening ceremony of the TAZC took place in January 1999. The activities of the Kwan Um School have received widespread media coverage and the number of attendees is increasing."[10] The other three centers in Israel practicing in the KUSZ are the Hasharon Zen Center,[11] the Ramat Gan Zen Group and the Pardes Hanna Zen Centre.[12]

Characteristics

According to the book Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest edited by Patricia O'Connell Killen and Mark Silk,

Mu Soeng, a longtime monk, describes the Kwan Um School as a unique amalgam of elements of Pure Land and Zen, chanting the name of the bodhisattva of compassion, and vigorous prostrations that are characteristic of Korean folk Buddhist practice. The Kwan Um School emphasizes socially engaged 'together action' by groups of followers living in a common house, koan or mantra practice tools, and a pastor-parishioner relationship between monks and laypersons characteristic of the Chogye order in Korea.[13]

As Mu Soeng indicates, one of the key tenets to practice is what Seungsahn often called "together action." Many members actually live in the zen centers, and one of the rules is that personal biases must be set aside for the good of the community. Also, chanting and prostrations, in addition to zazen, are very important forms of meditation for the school—aimed at clearing the mind of students.[14] The school website says, "Prostrations could be likened to the 'emergency measure' for clearing the mind. They are a very powerful technique for seeing the karma of a situation because both the mind and the body are involved. Something that might take days of sitting to digest may be digested in a much shorter time with prostrations. The usual practice here is to do 1000 bows a day (actually 1080). This can be done all at once or as is usually the case, spread out through the day."[15] The number of prostrations students often perform varies in part on their physical ability, though at least 108 and up to 1080 per day is usual. Also unique in the KUSZ is the fact that celibacy is not required of those who are ordained.[7] Rather, Seungsahn created the idea of a "Bodhisattva Monk," which essentially is an individual who can be married and hold a job but also be a monk in the order.[1] This status has now been superseded in the KUSZ by "Bodhisattva Teacher", who takes the 48 precepts but is not considered an ordained monk.

Seungsahn also held unorthodox views on Zen practice in Western culture, and was open to the idea of his dharma heirs starting their own schools as he had done, Dae Gak and George Bowman (Bomun) being two examples. Seung Sahn is quoted as having said, "As more Zen Masters appear, their individual styles will emerge. Perhaps some of them will make their own schools. So maybe, slowly, this Korean style will disappear and be replaced by an American style or American styles. But the main line does not change."[16] Author Kenneth Kraft offers an apt quote from Seungsahn on the issue of Zen and Western culture in his book Zen, Tradition and Transition (pp. 194–195),

When Bodhidharma came to China, he became the First Patriarch of Zen. As the result of a 'marriage' between Vipassana-style Indian meditation and Chinese Taoism, Zen appeared. Now it has come to the West, and what is already here? Christianity, Judaism, and so forth. When Zen 'gets married' to one of these traditions, a new style of Buddhism will appear. Perhaps there will be a woman Matriarch and all Dharma transmission will go only from woman to woman. Why not? So everyone, you must create American Buddhism."[1] In The Faces of Buddhism in America edited by Charles S. Prebish, Mu Soeng states that, "A case has been made that the culture of Kwan um Zen School is hardly anything more than an expression of Seung Sahn's personality as it has been shaped by the Confucian-Buddhist amalgam in Korea during the last thousand years.[2]

Kyol Che

During the summer and winter months, The Kwan Um School of Zen offers a Kyol Che (meaning "tight dharma")—a 21- to 90-day intensive silent meditation retreat. In Korea, both the summer and winter Kyol Che last a duration of 90 days, while the Providence Zen Center offers three weeks in the summer and 90 days in winter. Arrangements can be made for shorter stays for those with busy schedules. A Kyol Che provides a structured environment for meditators. Participation in one of these intensive retreats offers individuals the chance to free themselves from intellectual attachments and develop compassion. Participants have no contact with the outside world while undergoing a retreat, and the only literature permitted are those works written by Seungsahn. They are in practice from 4:45 a.m. to 9:45 p.m. each day, and are not permitted to keep a diary during their stay. Talking is only permitted when absolute necessity arises and during dokusan (Chinese: 独参), a private meeting with a teacher. The school also offers Yong Maeng Jong Jins, which are two- to seven-day silent retreats complete with dokusan with a Ji Do Poep Sa Nim or Soen Sa Nim (Zen master).[14][17][18][19]

Hierarchy

There are essentially four kinds of teachers in the Kwan Um tradition, all having attained a varying degree of mastery and understanding.

- A dharma teacher is an individual that has taken the Ten Precepts, completed a minimum of four years of training and a minimum of eight weekend retreats, understood basic Zen teaching and has been confirmed by a Soen Sa Nim to receive the title. These individuals can give a Dharma talk but may not respond to audience questions.

- A senior Dharma teacher is a Dharma teacher who, after a minimum of five years, has been confirmed by a Soen Sa Nim and has taken the Sixteen precepts. These individuals are given greater responsibility than a Dharma teacher, are able to respond to questions during talks, and give consulting interviews.

- A Ji Do Poep Sa Nim (JDPSN) (or "dharma master") is an authorized individual that has completed kōan training, having received inka, and is capable of leading a retreat. Completing kōan training is the first step toward becoming a JDPSN, followed by a nomination to receive inka by the individual's senior Dharma teacher. The individual is then assessed by five Dharma teachers, one being the nominating party, and the other four being independent Dharma teachers. The nominee must demonstrate an aptitude for the task of teaching, showing the breadth of their understanding in their daily conduct. Should the nominee be approved to be granted the title of JDPSN, a ceremony is held thereafter and the student engages in public Dharma combat with a number of students and teachers. Provided that the individual demonstrates a superior understanding to that of these students, they then receive the title. They are then given a kasa and keisaku and undergo a period of teacher training.

- A Soen Sa Nim (Zen master) is a JDPSN that has received full Dharma transmission master to master. The title is most often used in reference to Seungsahn, but all Zen masters in the Kwan Um tradition have the title Soen Sa Nim.[20]

An Abbot serves a Zen center in an administrative capacity and does not necessarily provide spiritual direction, though several are Soen Sa Nims. These individuals take care of budgets and other such tasks.[19][20]

Guiding Dharma teacher

School Abbot

Head teacher (Europe)

- Bon Shim Soen Sa Nim

Other Soen Sa Nims:

- Wu Kwang

- Bon Yeon

- Subong (deceased)

- Wubong (deceased)

- Hae Kwang

- Bon Yo Grazyna Perl, guiding teacher for France, Slovakia, the UK and Belgium

- Dae Bong

- Bon Haeng

- Bon Soeng

- Dae Kwan

- Chong Gak Shim

- Dae Soen Haeng

- Ji Kwang Soen Sa Nim

- Bon Hae Soen Sa Nim

Inactive

- Sogong

New schools

- Bomun (George Bowman)

- Dae Gak

- Ji Bong (Golden Wind Zen Order)

Controversies

In late 1985 through 1986, members within the Kwan Um School of Zen learned that Seungsahn had previously had sexual relations with a few of his female students.[21] According to Sandy Boucher in Turning the Wheel: American Women Creating the New Buddhism:

The sexual affairs were apparently not abusive or hurtful to the women. By all accounts, they were probably strengthening and certainly gave the women access to power. (However, no one can know if other women were approached by Soen Sa Nim, said nothing, and may have been hurt or at best confused, and left silently.) No one questions that Soen Sa Nim is a strong and inspiring teacher and missionary, wholly committed to spreading the Dharma, who has helped many people by his teachings and by his creation of institutions in which they can practice Zen. In his organization he has empowered students, some of them women, by giving them the mandate to teach and lead. And he has speculated, in a positive vein, on the coming empowerment of women in religion and government. Even his critics describe him as a dynamic teacher from whom they learned a great deal. On the other hand, former students point to secrecy, hypocrisy, an organization in which the people on top have power and information that they do not share with those farther down.[22]

James Ishmael Ford had this to say on the relationships:

For a while the future direction of Seung Sahn's institution was in doubt, and, as happened in the similarly affected Japanese-derived centers, quite a number of people left. It's not possible to adequately acknowledge the hurt and dismay that followed in the wake of these and similar scandals at other centers. In part because of their willingness to address the reality of ethical concerns, The Kwan Um School is now the single largest Zen institution in the West.[21]

Gallery

-

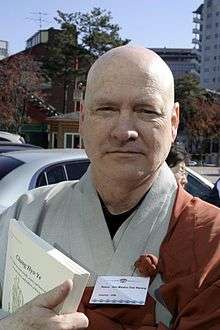

Bon Haeng

-

Dae Bong

-

Bon Soeng

-

Dae Kwan

-

Hyon Gak Sunim

-

Bo Haeng Sunim

-

Dae Won Sunim

-

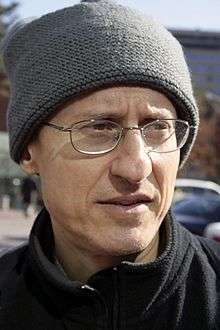

Andrzej Stec, JDPSN

See also

- Korean Buddhism

- Buddhism in the United States

- Cambridge Zen Center

- Chogye International Zen Center

- Musangsa

- Tel Aviv Zen Center

- Timeline of Zen Buddhism in the United States

- The Compass of Zen

- Wonkwangsa International Zen Temple

Notes

- 1 2 3 Kraft, 182; 194-195

- 1 2 Faces of Buddhism in America; 121-123

- ↑ Dharma Zen Center

- ↑ Empty Gate Zen Center

- ↑ About the Dharma Zen Center

- ↑ About the Providence Zen Center

- 1 2 Luminous Passage; 32-34

- ↑ Strecker, 106-107

- 1 2 Dharma Centre

- 1 2 3 Westward Dharma, 59; 111; 156; 159; 183; 186

- ↑ Hasharon Zen Center

- ↑ Ramat Gan Zen Group

- ↑ O'Connell; 119, 136

- 1 2 Queen, 458

- ↑ Why We Bow

- ↑ Transmission to the West: An interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn

- ↑ Riess, 243

- ↑ Hedgpath

- 1 2 Glossary of Terms

- 1 2 Ford, 105

- 1 2 Ford, 101

- ↑ Boucher, 228-223

References

- Boucher, Sandy (1993). Turning the Wheel: American Women Creating the New Buddhism. Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-7305-9.

- Ford, James Ishmael (2006). Zen Master Who?. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-509-8.

- Hedgpath, Nancy Brown (Fall 1988). "First Kyol Che". Primary Point. Kwan Um School of Zen. 5 (3). Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- Kraft, Kenneth (1988). Zen: Tradition and Transition. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3162-X.

- O'Connell, Patricia; Mark Silk (2004). Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest: The None Zone. AltaMira Press. ISBN 0-7591-0625-8.

- Queen, Christopher S (2000). Engaged Buddhism in the West. Wisdom publications. ISBN 0-86171-159-9.

- Prebish, Charles S.; Baumann, Martin (2002). Westward Dharma: Buddhism Beyond Asia. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22625-9.

- Prebish, Charles S.; Kenneth Ken'ichi Tanaka (1998). The Faces of Buddhism in America. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21301-7.

- Prebish, Charles S (1999). Luminous Passage: The Practice and Study of Buddhism in America. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21697-0.

- Riess, Jana (2002). Spiritual Traveler: A Guide to Sacred Sites and Peaceful Places. Hidden Spring. ISBN 1-58768-008-4.

- Strecker, Zoe Ayn (2007). Kentucky Off the Beaten Path, 8th edition. Globe Pequot. ISBN 0-7627-4201-1.

External links

- Kwan Um United States

- Kwan Um Europe

- Kwan Um Czech Republic

- Kwan Um Germany

- Kwan Um Hungary

- Kwan Um Poland

- Kwan Um Russia

- Kwan Um Lithuania

- Su Bong Zen Monastery, Hong Kong秀峰禪院

- Empty Gate Zen Center of Berkeley, CA

- Dharma Zen Center of Los Angeles, CA

- Zen Center of Bratislava, Slovakia