Vipassanā

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Mindfulness |

|---|

|

|

Other |

| Category:Mindfulness |

Vipassanā (Pāli) or vipaśyanā (Sanskrit: विपश्यना; Myanmar: ဝိပဿနာ; Chinese: 觀 guān; Standard Tibetan: ལྷག་མཐོང་, lhaktong; Wyl. lhag mthong) in the Buddhist tradition means insight into the true nature of reality,[1] namely as the Three marks of existence: impermanence, suffering or unsatisfactoriness, and the realisation of non-self. Presectarian Buddhism emphasized the practice of Dhyana, but early in the history of Buddhism Vipassanā gained a prominent place in the teachings.

Vipassanā meditation has been reintroduced in the Theravada-tradition by Ledi Sayadaw and Mogok Sayadaw and popularized by Mahasi Sayadaw,[2][3][4] S. N. Goenka, and the Vipassana movement, [5] in which mindfulness of breathing and of thoughts, feelings and actions are being used to gain insight into the true nature of reality. Due to the popularity of Vipassanā-meditation, the mindfulness of breathing has gained further popularity in the west as mindfulness.[5]

Etymology

Vipassanā is a Pali word from the Sanskrit prefix "vi-" and verbal root paś. It is often translated as "insight" or "clear-seeing," though, the "in-" prefix may be misleading; "vi" in Indo-Aryan languages is equivalent to the Latin "dis." The "vi" in vipassanā may then mean to see into, see through or to see 'in a special way.'[1] Alternatively, the "vi" can function as an intensive, and thus vipassanā may mean "seeing deeply."

A synonym for "Vipassanā" is paccakkha (Pāli; Sanskrit: pratyakṣa), "before the eyes," which refers to direct experiential perception. Thus, the type of seeing denoted by "vipassanā" is that of direct perception, as opposed to knowledge derived from reasoning or argument.

In Tibetan, vipaśyanā is lhagthong (wylie: lhag mthong). The term "lhag" means "higher", "superior", "greater"; the term "thong" is "view" or "to see". So together, lhagthong may be rendered into English as "superior seeing", "great vision" or "supreme wisdom." This may be interpreted as a "superior manner of seeing", and also as "seeing that which is the essential nature." Its nature is a lucidity—a clarity of mind.[6]

Henepola Gunaratana defined Vipassanā as:

Looking into something with clarity and precision, seeing each component as distinct and separate, and piercing all the way through so as to perceive the most fundamental reality of that thing"[1]

Insight

Origins

According to Richard Gombrich a development took place in early Buddhism resulting in a change in doctrine, which considered prajna to be an alternative means to "enlightenment".[7] The suttas contain traces of ancient debates between Mahayana and Theravada schools in the interpretation of the teachings and the development of insight. In the sutta pitaka the term "vipassanā" is hardly mentioned, while they frequently mention jhana as the meditative practice to be undertaken.[8][note 1]

According to Vetter and Bronkhorst, dhyāna itself constituted the original "liberating practice".[9][10][11] Vetter further argues that the eightfold path constitutes a body of practices which prepare one, and lead up to, the practice of dhyana.[12] Norman notes that "the Buddha's way to release [...] was by means of meditative practices."[13] Out of these debates developed the idea that bare insight suffices to reach liberation, by discerning the Three marks (qualities) of (human) existence (tilakkhana), namely dukkha (suffering), anatta (non-self) and anicca (impermanence).[14]

Sudden insight

The Sthaviravāda, one of the early Buddhist schools from which the Theravada-tradition originates, emphasized sudden insight:

In the Sthaviravada [...] progress in understanding comes all at once, 'insight' (abhisamaya) does not come 'gradually' (successively - anapurva).[15]

The Mahasanghika, another one of the early Buddhist schools, had the doctrine of ekaksana-citt, "according to which a Buddha knows everything in a single thought-instant".[16] This process however, meant to apply only to the Buddha and Peccaka buddhas. Lay people may have to experience various levels of insights to become fully enlightened.

The Mahayana-tradition emphasizes prajna, insight into sunyata, dharmata, the two truths doctrine, clarity and emptiness, or bliss and emptiness:[17]

[T]he very title of a large corpus of early Mahayana literature, the Prajnaparamita, shows that to some extent the historian may extrapolate the trend to extol insight, prajna, at the expense of dispassion, viraga, the control of the emotions.[18]

Although Theravada and Mahayana are commonly understood as different streams of Buddhism, their practice however, may reflect emphasis on insight as a common denominator:

In practice and understanding Zen is actually very close to the Theravada Forest Tradition even though its language and teachings are heavily influenced by Taoism and Confucianism.[19][note 2]

The emphasis on insight is discernible in the emphasis in Chán on sudden insight,[15] though in the Chán-tradition this insight is to be followed by gradual cultivation.[note 3]

Relation with samatha

In the Theravada-tradition, but also in Tibetan Buddhism, two types of meditation Buddhist practices are being followed, namely samatha (Pāli; Sanskrit: śamatha; "calm") and vipassana (insight).[21] Samatha is a primary meditation aimed at calming the mind, and it is also being used in other Indian traditions, notably Raja yoga.

Contemporary Theravada orthodoxy regards samatha as a preparation for vipassanā, pacifying the mind and strengthening the concentration in order to allow the work of insight, which leads to liberation. In contrast, the Vipassana Movement argues that insight levels can be discerned without the need for developing samatha further due to the risks of going out of course when strong samatha is developed.[22] For this innovation the Vipassana Movement has been criticised, especially in Sri Lanka.[23][24]

Though both terms appear in the Sutta Pitaka[note 4], Gombrich and Brooks argue that the distinction as two separate paths originates in the earliest interpretations of the Sutta Pitaka,[14] not in the suttas themselves.[29][note 5] According to Gombrich, the distinction between vipassanā and samatha did not originate in the suttas, but in the interpretation of the suttas.[14][note 6] Various traditions disagree which techniques belong to which pole.[31]

Vipassanā meditation

Vipassanā can be cultivated by the practice that includes contemplation and introspection although primarily awareness and observation of bodily sensations. The practices may differ in the modern Buddhist traditions and non-sectarian groups according to the founder but the main objective is to develop insight.

Theravāda

Insight in the Four Noble Truths

According to the Theravada-tradition, Buddhist practices leads to insight in the Four Noble Truths, which can only be reached by practising the Noble Eightfold Path. According to Theravada tradition enlightenment or Nibbana can only be attained by discerning all Vipassana insight levels when the Eightfold Noble Path is followed ardently. This is a developmental process where various Vipassana insights are discerned and the final enlightenment may come suddenly as proposed by other schools.

Vipassanā movement

The term vipassana became popular due to the influence of the Vipassana movement which started in the 1950s in Burma. It has come to be considered a practical solution to handle emotions in a complex society.

The Vipassanā Movement, also known as the Insight Meditation Movement, refers to a number of schools of modern Theravāda Buddhism, especially the Thai Forest Tradition and the "New Burmese Method", which emphasize development of insight into the three marks of existence as a means to become awakened and enter the Stream.

The modern influences[5] on the traditions of Sri Lanka, Burma, Laos and Thailand originating from various Theravāda teachers like Ledi sayadaw, Mogok Sayadaw who was less known to the West due to lack of International Mogok Centres, Mahasi Sayadaw, Ajahn Chah, and Dipa Ma, as well as derivatives from those traditions such as the movement led by S. N. Goenka. The Vipassanā Movement also includes contemporary American Buddhist teachers such as Joseph Goldstein, Tara Brach, Gil Fronsdal, Sharon Salzberg, and Jack Kornfield.

In the Vipassanā Movement, the emphasis is on the Satipatthana Sutta and the use of mindfulness to gain insight into the impermanence of the self-view.

Vipassana-meditation

Vipassanā-meditation uses mindfulness of breathing, combined with the contemplation of impermanence, to gain insight into the true nature of this reality. All phenomena are investigated, and concluded to be painful and unsubstantial, without an immortal entity or self-view, and in its ever-changing and impermanent nature.[32][18]

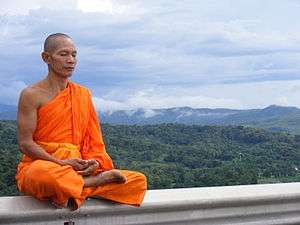

Mindfulness of breathing is described throughout the Sutta Pitaka. The Satipatthana Sutta describes it as going into the forest and sitting beneath a tree and then to simply watch the breath. If the breath is long, to notice that the breath is long, if the breath is short, to notice that the breath is short.[33][34]

By observing the breath one becomes aware of the perpetual changes involved in breathing, and the arising and passing away of mindfulness. One can also be aware of and gain insight into impermanence through the observation of bodily sensations and their nature of arising and passing away.[35]

Stages in the practice

Vipassanā jhanas are stages that describe the development of vipassanā meditation practice as described in modern Burmese Vipassana meditation.[36] Mahasi Sayadaw's student Sayadaw U Pandita described the four vipassanā jhanas as follows:[37]

- The meditator first explores the body/mind connection as one, nonduality; discovering three characteristics. The first jhana consists in seeing these points and in the presence of vitakka and vicara. Phenomena reveal themselves as appearing and ceasing.

- In the second jhana, the practice seems effortless. Vitaka and vicara both disappear.

- In the third jhana, piti, the joy, disappears too: there is only happiness (sukha) and concentration.

- The fourth jhana arises, characterised by purity of mindfulness due to equanimity. The practice leads to direct knowledge. The comfort disappears because the dissolution of all phenomena is clearly visible. The practice will show every phenomenon as unstable, transient, disenchanting. The desire of freedom will take place.

Eventually Vipassanā-meditation leads to insight into the impermanence of all phenomena, and thereby lead to a permanent liberation.[18]

Mahāyāna

Vajrayana

Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism employed both deductive investigation (applying ideas to experience) and inductive investigation (drawing conclusions from direct experience) in the practice of vipaśyanā.[note 7][note 8] According to Leah Zahler, only the tradition of deductive analysis in vipaśyanā was transmitted to Tibet in the sūtrayāna context.[note 9]

In Tibet direct examination of moment-to-moment experience as a means of generating insight became exclusively associated with vajrayāna.[40][note 10][note 11]

Mahāmudrā and Dzogchen

Mahāmudrā and Dzogchen use vipaśyanā extensively. This includes some methods of the other traditions, but also their own specific approaches. They place a greater emphasis on meditation on symbolic images. Additionally in the Vajrayāna (tantric) path, the true nature of mind is pointed out by the guru, and this serves as a direct form of insight.[note 12]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Thanissaro Bhikkhu: "If you look directly at the Pali discourses — the earliest extant sources for our knowledge of the Buddha's teachings — you'll find that although they do use the word samatha to mean tranquillity, and vipassanā to mean clear-seeing, they otherwise confirm none of the received wisdom about these terms. Only rarely do they make use of the word vipassanā — a sharp contrast to their frequent use of the word jhana. When they depict the Buddha telling his disciples to go meditate, they never quote him as saying "go do vipassanā," but always "go do jhana." And they never equate the word vipassanā with any mindfulness techniques."[8]

- ↑ Khantipalo recommends the use of the koan-like question "Who?" to penetrate "this not-self-nature of the five aggregates": "In Zen Buddhism this technique has been formulated in several koans, such as 'Who drags this corpse around?'"[20]

- ↑ This "gradual training" is expressed in teachings as the Five ranks of enlightenment, Ten Ox-Herding Pictures which detail the steps on the Path, The Three mysterious Gates of Linji, and the Four Ways of Knowing of Hakuin.

- ↑ See, for example:

AN 4.170 (Pali):

“Yo hi koci, āvuso, bhikkhu vā bhikkhunī vā mama santike arahattappattiṁ byākaroti, sabbo so catūhi maggehi, etesaṁ vā aññatarena.

Katamehi catūhi? Idha, āvuso, bhikkhu samathapubbaṅgamaṁ vipassanaṁ bhāveti[...]

Puna caparaṁ, āvuso, bhikkhu vipassanāpubbaṅgamaṁ samathaṁ bhāveti[...]

Puna caparaṁ, āvuso, bhikkhu samathavipassanaṁ yuganaddhaṁ bhāveti[...]

Puna caparaṁ, āvuso, bhikkhuno dhammuddhaccaviggahitaṁ mānasaṁ hoti[...]

English translation:

Friends, whoever — monk or nun — declares the attainment of arahantship in my presence, they all do it by means of one or another of four paths. Which four?

There is the case where a monk has developed insight preceded by tranquility. [...]

Then there is the case where a monk has developed tranquillity preceded by insight. [...]

Then there is the case where a monk has developed tranquillity in tandem with insight. [...]

"Then there is the case where a monk's mind has its restlessness concerning the Dhamma [Comm: the corruptions of insight] well under control.[25]

AN 2.30 Vijja-bhagiya Sutta, A Share in Clear Knowing:

"These two qualities have a share in clear knowing. Which two? Tranquility (samatha) & insight (vipassana).

"When tranquility is developed, what purpose does it serve? The mind is developed. And when the mind is developed, what purpose does it serve? Passion is abandoned.

"When insight is developed, what purpose does it serve? Discernment is developed. And when discernment is developed, what purpose does it serve? Ignorance is abandoned.

"Defiled by passion, the mind is not released. Defiled by ignorance, discernment does not develop. Thus from the fading of passion is there awareness-release. From the fading of ignorance is there discernment-release."[26]

SN 43.2 (Pali): "Katamo ca, bhikkhave, asaṅkhatagāmimaggo? Samatho ca vipassanā".[27] English translation: "And what, bhikkhus, is the path leading to the unconditioned? Serenity and insight."[28] - ↑ Brooks: "While many commentaries and translations of the Buddha's Discourses claim the Buddha taught two practice paths, one called "shamata" and the other called "vipassanā," there is in fact no place in the suttas where one can definitively claim that."[29]

- ↑ Henepola Gunaratana: "The classical source for the distinction between the two vehicles of serenity and insight is the Visuddhimagga."[30]

- ↑ Corresponding respectively to the "contemplative forms" and "experiential forms" in the Theravāda school described above

- ↑ Leah Zahler: "The practice tradition suggested by the Treasury [Abhidharma-kośa] .. . — and also by Asaṅga's Grounds of Hearers — is one in which mindfulness of breathing becomes a basis for inductive reasoning on such topics as the five aggregates; as a result of such inductive reasoning, the meditator progresses through the Hearer paths of preparation, seeing, and meditation. It seems at least possible that both Vasubandhu and Asaṅga presented their respective versions of such a method, analogous to but different from modern Theravāda insight meditation, and that Gelukpa scholars were unable to reconstruct it in the absence of a practice tradition because of the great difference between this type of inductive meditative reasoning based on observation and the types of meditative reasoning using consequences (thal 'gyur, prasaanga) or syllogisms (sbyor ba, prayoga) with which Gelukpas were familiar. Thus, although Gelukpa scholars give detailed interpretations of the systems of breath meditation set forth in Vasubandu's and Asaṅga's texts, they may not fully account for the higher stages of breath meditation set forth in those texts [...] it appears that neither the Gelukpa textbook writers nor modern scholars such as Lati Rinpoche and Gendun Lodro were in a position to conclude that the first moment of the fifth stage of Vasubandhu's system of breath meditation coincides with the attainment of special insight and that, therefore, the first four stages must be a method for cultivating special insight [although this is clearly the case].[38]

- ↑ This tradition is outlined by Kamalaśīla in his three Bhāvanākrama texts (particularly the second one), following in turn an approach described in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra.[39] One scholar describes his approach thus: "the overall picture painted by Kamalaśīla is that of a kind of serial alternation between observation and analysis that takes place entirely within the sphere of meditative concentration" in which the analysis portion consists of Madhyamaka reasonings.[39]

- ↑ According to contemporary Tibetan scholar Thrangu Rinpoche the Vajrayana cultivates direct experience. Thrangu Rinpoche: "The approach in the sutras [...] is to develop a conceptual understanding of emptiness and gradually refine that understanding through meditation, which eventually produces a direct experience of emptiness [...] we are proceeding from a conceptual understanding produced by analysis and logical inference into a direct experience [...] this takes a great deal of time [...] we are essentially taking inferential reasoning as our method or as the path. There is an alternative [...] which the Buddha taught in the tantras [...] the primary difference between the sutra approach and the approach of Vajrayana (secret mantra or tantra) is that in the sutra approach, we take inferential reasoning as our path and in the Vajrayana approach, we take direct experience as our path. In the Vajrayana we are cultivating simple, direct experience or "looking." We do this primarily by simply looking directly at our own mind."[40]

- ↑ Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche also explains: "In general there are two kinds of meditation: the meditation of the paṇḍita who is a scholar and the nonanalytical meditation or direct meditation of the kusulu, or simple yogi. . . the analytical meditation of the paṇḍita occurs when somebody examines and analyzes something thoroughly until a very clear understanding of it is developed. . . The direct, nonanalytical meditation is called kusulu meditation in Sanskrit. This was translated as trömeh in Tibetan, which means "without complication" or being very simple without the analysis and learning of a great scholar. Instead, the mind is relaxed and without applying analysis so it just rests in its nature. In the sūtra tradition, there are some nonanalytic meditations, but mostly this tradition uses analytic meditation."[41]

- ↑ Thrangu Rinpoche describes the approach using a guru: "In the Sūtra path one proceeds by examining and analyzing phenomena, using reasoning. One recognizes that all phenomena lack any true existence and that all appearances are merely interdependently related and are without any inherent nature. They are empty yet apparent, apparent yet empty. The path of Mahāmudrā is different in that one proceeds using the instructions concerning the nature of mind that are given by one's guru. This is called taking direct perception or direct experiences as the path. The fruition of śamatha is purity of mind, a mind undisturbed by false conception or emotional afflictions. The fruition of vipaśyanā is knowledge (prajnā) and pure wisdom (jñāna). Jñāna is called the wisdom of nature of phenomena and it comes about through the realization of the true nature of phenomena.[42]

References

- 1 2 3 Gunaratana 2011, p. 21.

- ↑ King 1992, p. 132-137.

- ↑ Nyanaponika 1998, p. 107-109.

- ↑ Koster 2009, p. 9-10.

- 1 2 3 McMahan 2008.

- ↑ Ray (2004) p.74

- ↑ gombrich 1997, p. 131.

- 1 2 Thanissaro Bhikkhu & Year Unknown.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, p. xxi-xxii.

- ↑ Bronkhorst 1993.

- ↑ Cousins 1996, p. 58.

- ↑ Vetter 1988, p. xxx.

- ↑ Norman 1997, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 Gombrich 1997, p. 96-144.

- 1 2 Warder 2000, p. 284.

- ↑ Gomez 1991, p. 69.

- ↑ Defined by Reginald A. Ray. ""Vipashyana," by Reginald A. Ray. ''Buddhadharma: The Practitioner's Quarterly'', Summer 2004". Archive.thebuddhadharma.com. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- 1 2 3 Gombrich 1997, p. 133.

- ↑ "Through the Looking Glass, ''Essential Buddhism''". Bhikkhucintita.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ Khantipalo 1984, p. 71.

- ↑ "What is Theravada Buddhism?". Access to Insight. Access to Insight. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ↑ Bond 1992, p. 167.

- ↑ Bond 1992, p. 162-171.

- ↑ Robert H. Sharf, Division of Social and Transcultural Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University

- ↑ "AN 4.170 Yuganaddha Sutta: ''In Tandem''. Translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu". Accesstoinsight.org. 2010-07-03. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ "AN 2.30 Vijja-bhagiya Sutta, ''A Share in Clear Knowing''. Translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu". Accesstoinsight.org. 2010-08-08. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ "SN 43.2". Agama.buddhason.org. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ Bikkhu Bodhi, The Connected Discourses of the Buddha, p. 1373

- 1 2 Brooks 2006.

- ↑ "Henepola Gunaratana, ''The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation''". Accesstoinsight.org. 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ Schumann 1974.

- ↑ Nyanaponika 1998.

- ↑ Majjhima Nikaya, Sutta No. 118, Section No. 2, translated from the Pali

- ↑ Satipatthana Sutta

- ↑ "The Art of Living: Vipassana Meditation". Dhamma.org. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ Ingram, Daniel (2008), Mastering the core teachings of the Buddha, Karnac Books, p.246

- ↑ Sayadaw U Pandita, In this very life

- ↑ Zahler 108, 113

- 1 2 "Some Notes on Kamalasila's Understanding of Insight Considered as the Discernment of Reality (bhūta-pratyavekṣā)", by Martin Adam, Buddhist Studies Review, Vol. 25, No.2, 2008, p 3

- 1 2 Pointing out the Dharmakaya by Thrangu Rinpoche. Snow Lion: 2003. ISBN 1-55939-203-7, pg 56

- ↑ The Practice of Tranquillity & Insight: A Guide to Tibetan Buddhist Meditation by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche. Shambhala Publications: 1994. ISBN 0-87773-943-9 pg 91-93

- ↑ Thrangu Rinpoche, Looking Directly at Mind : The Moonlight of Mahāmudrā

Sources

- Bond, George D. (1992), The Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993), The Two Traditions Of Meditation In Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- Brooks, Jeffrey S. (2006), A Critique of the Abhidhamma and Visuddhimagga

- Buswell, Robert E. JR; Gimello, Robert M. (editors) (1994), Paths to Liberation. The Marga and its Transformations in Buddhist Thought, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Fronsdal, Gil (1998), Insight Meditation in the United States: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness. In: Charles S. Prebish and Kenneth K. Tanaka, The Faces of Buddhism in America, Chapter 9

- Glickman, Marshall (1998), Beyond the Breath: Extraordinary Mindfulness Through Whole-Body Vipassana Meditation, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 1-58290-043-4

- Gombrich, Richard F. (1997), How Buddhism Began. The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Gunaratana, Henepola (2011), Mindfulness in plain English, Wisdom Publications, p. 21, ISBN 978-0861719068

- Khantipalo, Bikkhu (1984), Calm and Insight. A buddhist Manual for Meditators, London and Dublin: Curzon Press Ltd.

- King, Winston L. (1992), Theravada Meditation. The Buddhist Transformation of Yoga, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Koster, Frits (2009), Basisprincipes Vipassana-meditatie. Mindfulness als weg naar bevrijdend inzicht, Asoka

- Mathes, Klaus-Dieter (2003), Blending the Sūtras with the Tantras: The influence of Maitrīpa and his circle on the formation of Sūtra Mahāmudrā in the Kagyu Schools. In: Tibetan Buddhist Literature and Praxis: Studies in its Formative Period, 900–1400. Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Oxford

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276

- Norman, K.R. (1997), A Philological Approach to Buddhism. The Bukkyo Dendo Kybkai Lectures 1994 (PDF), School ofOriental and African Studies (University of London)

- Nyanaponika (1998), Het hart van boeddhistische meditatie (The heart of Buddhist Meditation), Asoka

- Ray, Reginald A. (Ed.) (2004), In the Presence of Masters: Wisdom from 30 Contemporary Tibetan Buddhist Teachers, ISBN 1-57062-849-1

- Schmithausen, Lambert (1986), Critical Response. In: Ronald W. Neufeldt (ed.), "Karma and rebirth: Post-classical developments", SUNY

- Schumann, Hans Wolfgang (1974), Buddhism: an outline of its teachings and schools, Theosophical Pub. House

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997), One Tool Among Many. The Place of Vipassana in Buddhist Practice

- Vetter, Tilmann (1988), The Ideas and Meditative Practices of Early Buddhism, BRILL

- Warder, A.K. (2000), Indian Buddhism, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

External links

History

Background

- Insight Meditation Online From Buddhanet.net

- A Honed and Heavy Axe

- Mahasi Sayadaw, Satipatthana Vipassana: Criticisms and Replies

- Jeffrey S, Brooks, The Fruits (Phala) of the Contemplative Life

Practice

- Meditation From Yellowrobe.com

- Vipassana Meditation as taught by S.N. Goenka and his assistant teachers in the tradition of Sayagyi U Ba Khin at free centers worldwide

- Saddhamma Foundation Information about practicing Vipassana meditation.

- Practical Guidelines for Vipassanâ by Ayya Khema