Tripiṭaka

| Translations of Tripiṭaka | |

|---|---|

| English | Three Baskets |

| Pali | Tipiṭaka |

| Sanskrit |

त्रिपिटक Tripiṭaka |

| Bengali | ত্রিপিটক |

| Burmese |

ပိဋကတ် သုံးပုံ [pḭdəɡaʔ θóʊɴbòʊɴ] |

| Chinese |

三藏 (Pinyin: sānzàng) |

| Japanese |

三蔵 (さんぞう) (rōmaji: sanzō) |

| Khmer | ព្រះត្រៃបិដក |

| Korean |

삼장 (三臧) (RR: samjang) |

| Sinhala | ත්රිපිටකය |

| Thai | พระไตรปิฎก |

| Vietnamese | Tam tạng |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

Tripiṭaka, also referred to as Tipiṭaka or Pali Canon, is the traditional term for the Buddhist scriptures.[1][2] These are canonical texts revered as exclusively authoritative in Theravada Buddhism. The Mahayana Buddhism also reveres them as authoritative but, unlike Theravadins, it also reveres various derivative literature and commentaries that were composed much later.[1][3]

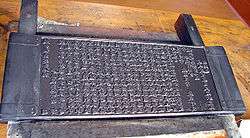

The Tripitakas were composed between about 500 BCE to about the start of the common era, likely written down for the first time in the 1st century BCE.[3] Each Buddhist sub-tradition had its own Tripitaka for its monasteries, written by its sangha, each set consisting of 32 books, in three parts or baskets of teachings: (1) the basket of expected discipline from monks (Vinaya Piṭaka), (2) basket of discourse (Sūtra Piṭaka, Nikayas), and (3) basket of special doctrine (Abhidharma Piṭaka).[1][3][4] The structure, the code of conduct and moral virtues in the Vinaya basket particularly, have similarities to some of the surviving Dharmasutra texts of Hinduism.[5] Much of the surviving Tripitaka literature is in Pali, some in Sanskrit, as well as other local Asian languages.[4]

Etymology

Tripiṭaka (Sanskrit: त्रिपिटक), also called Tipiṭaka (Pali), means Three Baskets. It is a compound Sanskrit word of tra (त्र) meaning three, and pitaka (पिटक) or pita (पिट) meaning "basket or box made from bamboo or wood" and "collection of writings", according to Monier-Williams.[6] These terms are also spelled without diacritics as Tripitaka and Tipitaka in scholarly literature.[1]

Chronology

The dating of the Tripitakas is unclear. Max Muller states that the texts were likely composed in the third century BCE, but transmitted orally from generation to generation just like the Vedas and the early Upanishads.[7] The first version, suggests Muller, was very likely reduced to writing in the 1st century BCE (nearly 500 years after the time of Buddha).[7]

According to the Tibetan historian Bu-ston, states Warder, around or before 1st century CE, there were eighteen schools of Buddhism and their Tripitakas were written down by then.[8] However, except for one version that has survived in full, and others of which parts have survived, all of these texts are lost to history or yet to be found.[8] The historical evidence preserved in Sri Lanka suggest that a complete Tripitaka was written down there in the 1st century BCE.[8] These texts were written down in four related Indo-European languages of South Asia: Sanskrit, Pali, Paisaci and Prakrit, sometime between 1st century BCE and 7th century CE.[8] Some of these were translated in East Asian languages such as Chinese, Tibetan and Mongolian by ancient visiting scholars, which though vast are incomplete.[9]

Wu and Chia state that emerging evidence, though uncertain, suggests that the earliest written Buddhist Tripitaka texts may have arrived in China from India by the 1st century BCE.[10]

The three categories

Tripitaka comprises the three main categories of texts that is the Buddhist canon. The three parts of the Pāli canon are not as contemporary as the traditional Buddhist account seems to suggest: the Sūtra Piṭaka is older than the Vinaya Piṭaka, and the Abhidharma Piṭaka represents scholastic developments originated at least two centuries after the other two parts of the canon. The Vinaya Piṭaka appears to have grown gradually as a commentary and justification of the monastic code (Prātimokṣa), which presupposes a transition from a community of wandering mendicants (the Sūtra Piṭaka period ) to a more sedentary monastic community (the Vinaya Piṭaka period). Even within the Sūtra Piṭaka it is possible to detect older and later texts.

Vinaya

Rules and regulations of monastic life that range from dress code and dietary rules to prohibitions of certain personal conducts.

Sutta

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

The Buddha delivered all his sermons in local language of northern India. These sermons were collected during 1st assembly just after the death of the Buddha. Later these teachings were translated into Sanskrit.

Abhidhamma

Philosophical and psychological discourse and interpretation of Buddhist doctrine.

In Indian Buddhist schools

Each of the Early Buddhist Schools likely had their own recensions of the Tripiṭaka. According to some sources, there were some Indian schools of Buddhism that had five or seven piṭakas.[11]

Mahāsāṃghika

The Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya was translated by Buddhabhadra and Faxian in 416 CE, and is preserved in Chinese translation (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1425).

The 6th century CE Indian monk Paramārtha wrote that 200 years after the parinirvāṇa of the Buddha, much of the Mahāsāṃghika school moved north of Rājagṛha, and were divided over whether the Mahāyāna sūtras should be incorporated formally into their Tripiṭaka. According to this account, they split into three groups based upon the relative manner and degree to which they accepted the authority of these Mahāyāna texts.[12] Paramārtha states that the Kukkuṭika sect did not accept the Mahāyāna sūtras as buddhavacana ("words of the Buddha"), while the Lokottaravāda sect and the Ekavyāvahārika sect did accept the Mahāyāna sūtras as buddhavacana.[13] Also in the 6th century CE, Avalokitavrata writes of the Mahāsāṃghikas using a "Great Āgama Piṭaka," which is then associated with Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Prajñāparamitā and the Daśabhūmika Sūtra.[14]

According to some sources, abhidharma was not accepted as canonical by the Mahāsāṃghika school.[15] The Theravādin Dīpavaṃsa, for example, records that the Mahāsāṃghikas had no abhidharma.[16] However, other sources indicate that there were such collections of abhidharma, and the Chinese pilgrims Faxian and Xuanzang both mention Mahāsāṃghika abhidharma. On the basis of textual evidence as well as inscriptions at Nāgārjunakoṇḍā, Joseph Walser concludes that at least some Mahāsāṃghika sects probably had an abhidharma collection, and that it likely contained five or six books.[17]

Caitika

The Caitikas included a number of sub-sects including the Pūrvaśailas, Aparaśailas, Siddhārthikas, and Rājagirikas. In the 6th century CE, Avalokitavrata writes that Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Prajñāparamitā and others are chanted by the Aparaśailas and the Pūrvaśailas.[14] Also in the 6th century CE, Bhāvaviveka speaks of the Siddhārthikas using a Vidyādhāra Piṭaka, and the Pūrvaśailas and Aparaśailas both using a Bodhisattva Piṭaka, implying collections of Mahāyāna texts within these Caitika schools.[14]

Bahuśrutīya

The Bahuśrutīya school is said to have included a Bodhisattva Piṭaka in their canon. The Satyasiddhi Śāstra, also called the Tattvasiddhi Śāstra, is an extant abhidharma from the Bahuśrutīya school. This abhidharma was translated into Chinese in sixteen fascicles (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1646).[18] Its authorship is attributed to Harivarman, a third-century monk from central India. Paramārtha cites this Bahuśrutīya abhidharma as containing a combination of Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna doctrines, and Joseph Walser agrees that this assessment is correct.[19]

Prajñaptivāda

The Prajñaptivādins held that the Buddha's teachings in the various piṭakas were nominal (Skt. prajñapti), conventional (Skt. saṃvṛti), and causal (Skt. hetuphala).[20] Therefore, all teachings were viewed by the Prajñaptivādins as being of provisional importance, since they cannot contain the ultimate truth.[21] It has been observed that this view of the Buddha's teachings is very close to the fully developed position of the Mahāyāna sūtras.[20] [21]

Sārvāstivāda

Scholars at present have "a nearly complete collection of sūtras from the Sarvāstivāda school"[22] thanks to a recent discovery in Afghanistan of roughly two-thirds of Dīrgha Āgama in Sanskrit. The Madhyama Āgama (Taishō Tripiṭaka 26) was translated by Gautama Saṃghadeva, and is available in Chinese. The Saṃyukta Āgama (Taishō Tripiṭaka 99) was translated by Guṇabhadra, also available in Chinese translation. The Sarvāstivāda is therefore the only early school besides the Theravada for which we have a roughly complete Sūtra Piṭaka. The Sārvāstivāda Vinaya Piṭaka is also extant in Chinese translation, as are the seven books of the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma Piṭaka. There is also the encyclopedic Abhidharma Mahāvibhāṣa Śāstra (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1545), which was held as canonical by the Vaibhāṣika Sarvāstivādins of northwest India.

Mūlasārvāstivāda

Portions of the Mūlasārvāstivāda Tripiṭaka survive in Tibetan translation and Nepalese manuscripts.[23] The relationship of the Mūlasārvāstivāda school to Sarvāstivāda school is indeterminate; their vinayas certainly differed but it is not clear that their Sūtra Piṭaka did. The Gilgit manuscripts may contain Āgamas from the Mūlasārvāstivāda school in Sanskrit.[24] The Mūlasārvāstivāda Vinaya Piṭaka survives in Tibetan translation and also in Chinese translation (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1442). The Gilgit manuscripts also contain vinaya texts from the Mūlasārvāstivāda school in Sanskrit.[24]

Dharmaguptaka

A complete version of the Dīrgha Āgama (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1) of the Dharmaguptaka school was translated into Chinese by Buddhayaśas and Zhu Fonian (竺佛念) in the Later Qin dynasty, dated to 413 CE. It contains 30 sūtras in contrast to the 34 suttas of the Theravadin Dīgha Nikāya. A. K. Warder also associates the extant Ekottara Āgama (Taishō Tripiṭaka 125) with the Dharmaguptaka school, due to the number of rules for monastics, which corresponds to the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya.[25] The Dharmaguptaka Vinaya is also extant in Chinese translation (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1428), and Buddhist monastics in East Asia adhere to the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya.

The Dharmaguptaka Tripiṭaka is said to have contained a total of five piṭakas.[19] These included a Bodhisattva Piṭaka and a Mantra Piṭaka (Ch. 咒藏), also sometimes called a Dhāraṇī Piṭaka.[26] According to the 5th century Dharmaguptaka monk Buddhayaśas, the translator of the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya into Chinese, the Dharmaguptaka school had assimilated the Mahāyāna Tripiṭaka (Ch. 大乘三藏).[27]

Mahīśāsaka

The Mahīśāsaka Vinaya is preserved in Chinese translation (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1421), translated by Buddhajīva and Zhu Daosheng in 424 CE.

Kāśyapīya

Small portions of the Tipiṭaka of the Kāśyapīya school survive in Chinese translation. An incomplete Chinese translation of the Saṃyukta Āgama of the Kāśyapīya school by an unknown translator circa the Three Qin (三秦) period (352-431 CE) survives.[28]

In the Theravada school

The complete Tripiṭaka set of the Theravāda school is written and preserved in Pali in the Pali Canon. Buddhists of the Theravāda school use the Pali variant Tipitaka to refer what is commonly known in English as the Pali Canon.

In Mahāyāna schools

The term Tripiṭaka had tended to become synonymous with Buddhist scriptures, and thus continued to be used for the Chinese and Tibetan collections, although their general divisions do not match a strict division into three piṭakas.[29] In the Chinese tradition, the texts are classified in a variety of ways,[30] most of which have in fact four or even more piṭakas or other divisions.

As a title

The Chinese form of Tripiṭaka, "sānzàng" (三藏), was sometimes used as an honorary title for a Buddhist monk who has mastered the teachings of the Tripiṭaka. In Chinese culture this is notable in the case of the Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang, whose pilgrimage to India to study and bring Buddhist text back to China was portrayed in the novel Journey to the West as "Tang Sanzang" (Tang Dynasty Tripiṭaka Master). Due to the popularity of the novel, the term "sānzàng" is often erroneously understood as a name of the monk Xuanzang. One such screen version of this is the popular 1979 Monkey (TV series).

The modern Indian scholar Rahul Sankrityayan is sometimes referred to as Tripitakacharya in reflection of his familiarity with the Tripiṭaka.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Tipitaka Encyclopedia Britannica (2015)

- ↑ "Buddhist Books and Texts: Canon and Canonization." Lewis Lancaster, Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd edition, pg 1252

- 1 2 3 Barbara Crandall (2012). Gender and Religion, 2nd Edition: The Dark Side of Scripture. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-1-4411-4871-1.

- 1 2 Richard F. Gombrich (2006). Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-134-21718-2.

- ↑ Oskar von Hinuber (1995), Buddhist Law according to the Theravada Vinaya: A Survey of Theory and Practice, Journal of International Association of Buddhist Studies, volume 18, number 1, pages 7-46

- ↑ Sir Monier Monier-Williams; Ernst Leumann; Carl Cappeller (2002). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 625. ISBN 978-81-208-3105-6.

- 1 2 Friedrich Max Müller (1899). The Six Systems of Indian Philosophy. Longmans, Green. pp. 19–29.

- 1 2 3 4 A. K. Warder (2000). Indian Buddhism. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 282–283. ISBN 978-81-208-1741-8.

- ↑ A. K. Warder (2000). Indian Buddhism. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-208-1741-8.

- ↑ Jiang Wu; Lucille Chia (2015). Spreading Buddha's Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. Columbia University Press. pp. 111–123. ISBN 978-0-231-54019-3.

- ↑ Skilling, Peter (1992), The Raksa Literature of the Sravakayana, Journal of the Pali Text Society, volume XVI, page 114

- ↑ Walser 2005, p. 51.

- ↑ Sree Padma. Barber, Anthony W. Buddhism in the Krishna River Valley of Andhra. 2008. p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Walser 2005, p. 53.

- ↑ "Abhidhamma Pitaka." Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- ↑ Walser 2005, p. 213.

- ↑ Walser 2005, p. 212-213.

- ↑ The Korean Buddhist Canon: A Descriptive Catalog (K 966)

- 1 2 Walser 2005, p. 52.

- 1 2 Dutt 1998, p. 118.

- 1 2 Harris 1991, p. 98.

- ↑ Bhikkhu Sujato: The Pali Nikāyas and Chinese Āgamas

- ↑ Preservation of Sanskrit Buddhist Manuscripts In the Kathmandu

- 1 2 Memory Of The World Register: Gilgit manuscripts

- ↑ Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 6

- ↑ Baruah, Bibhuti. Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism. 2008. p. 52

- ↑ Walser 2005, p. 52-53.

- ↑ A Dictionary of Buddhism, by Damien Keown, Oxford University Press: 2004

- ↑ Mizuno, Essentials of Buddhism, 1972, English version pub Kosei, Tokyo, 1996

- ↑ Nanjio, Catalogue of the Chinese Translations of the Buddhist Tripitaka, Clarendon, Oxford, 1883

Further reading

- Walser, Joseph (2005), Nāgārjuna in Context: Mahāyāna Buddhism and Early Indian Culture, Columbia Univ Pr, ISBN 978-0231131643

- Dutt, Nalinaksha (1998), Buddhist Sects in India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0428-7

- Harris, Ian Charles (1991), The Continuity of Madhyamaka and Yogacara in Indian Mahayana Buddhism, Brill Academic Pub, ISBN 9789004094482

External links

Pali Canon:

- Access to Insight has many suttas translated into English

- Tipitaka Network

- List of Pali Canon Suttas translated into English (ongoing)

- The Pali Tipitaka Project (texts in 7 Asian languages)

- The Sri Lanka Tripitaka Project Pali Canons has a searchable database of the Pali texts

- The Vietnamese Nikaaya (continuing, text in Vitenamese)

- Search in English translations of the Tipitaka

Myanmar Version of Buddhist Canon (6th revision):

- Buddhist Bible Myanmar Version (without original Pali text)

Chinese Buddhist Canon:

- Buddhist Text Translation Society: Sutra Texts

- BuddhaNet's eBook Library (English PDFs)

- WWW Database of Chinese Buddhist texts (English index of some East Asian Tripitakas)

- CBETA: Full Chinese language canon and extended canon (includes downloads)

Tibetan tradition:

- Kangyur & Tengyur Projects (Tibetan texts)

Tripitaka collections: