Levenshulme

| Levenshulme | |

Levenshulme |

|

| Population | 15,430 (2011 Census)[1] |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | SJ875945 |

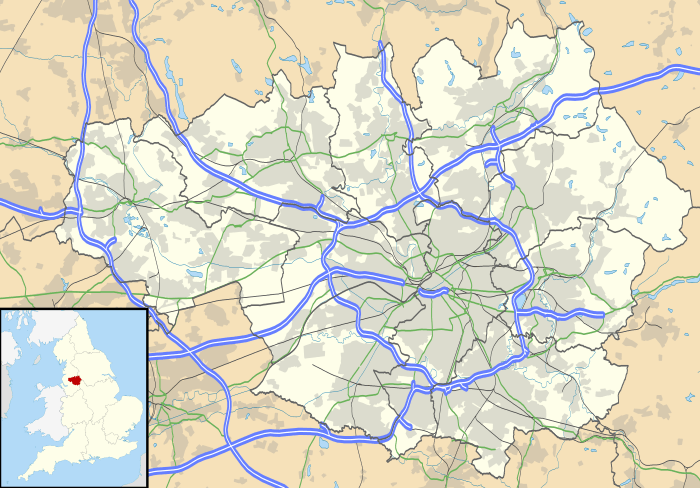

| Metropolitan borough | City of Manchester |

| Metropolitan county | Greater Manchester |

| Region | North West |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MANCHESTER |

| Postcode district | M19 |

| Dialling code | 0161 22x |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| EU Parliament | North West England |

| UK Parliament | Manchester Gorton |

|

|

Coordinates: 53°26′49″N 2°11′13″W / 53.447°N 2.187°W

Levenshulme is an area of Manchester in North West England bordering Fallowfield, Longsight, Gorton, Burnage, Heaton Chapel and Reddish, approximately halfway between Stockport and Manchester city centre 4 miles (6.4 km) away on the A6. Levenshulme is predominantly residential with a predominance of fast food shops, public houses and antique stores. It has a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic population of 15,430 at the 2011 Census. The Manchester to London railway line passes through Levenshulme railway station.

Historically in Lancashire, Levenshulme is a former township and became a part of Manchester in 1909. Levenshulme, like its neighbour Longsight, was historically a wealthy and middle class district of Manchester,[2][3] though in modern times has lost this status and population.

History

The very early history is so obscure as to be virtually non-existent. Many of the nearby suburbs, such as Withington, Didsbury, Gorton etc., had a history of developing as villages, but for some reason Levenshulme did not. It has had several names over the millennia (according to East Lancashire expert Eilert Ekwall), including: in 1246 it was called "de Lewyneshulm", in 1322 "Levensholme" and in 1587 it was called "Lensom". The name itself is derived from a possessive version of a person's name, "Leofwine's" and "holm", a Viking term meaning island (usually in a lake or river).[4] "Lywenshulme" also is referred to in the 1322 survey of Manchester and Collegiate Church charters refer to "Leysholme" (1556), "Lensholme" (1578) and "Lentsholme" (1635).[5] The "Hulme" element is common in Manchester, and was pronounced "Oom", hence Levenshulme was traditionally "Levenzoom" to the residents.[5]

The main A6, Stockport Road, dates from 1724 when a turnpike was built between Manchester and Stockport.[6]

The district of East Levenshulme used to be known as Talleyrand. It included Talleyrand House (later renamed as Barlow House) and a street, Talleyrand Row.[7] It was said the French statesman Talleyrand once stayed there during his exile from France (French Revolution), presumably at some point during 1792–94.[8] The place name "Talley Rand" is also found on the old post office sorting labels displayed in the POD cafe based in the former main post office.

Legend has it that the famous highwayman Dick Turpin regularly visited the Blue Bell Inn on Barlow Road which shares the name of his birthplace. There has been an inn on this site for 700 years.[9] The current pub was built after the previous Blue Bell Inn was destroyed during a German bombing raid in the Second World War.

Levenshulme, a dependency of Withington, was once the feudal lands held by the Lord of the Manor of Levenshulme from 1319–17th century. In 1319 possession was given to William Legh of Baguley by his grandfather Sir William de Baguley of Baguley in Cheshire. William Legh's descendants continued to hold the Manor until the 17th century.[10]

In 1917, the McVitie & Price biscuit factory was opened.

Housing

The typical housing of Levenshulme consists of terraced houses, the majority of which were built circa 1880–1890. The style of houses are what are known colloquially as "two up-two downs". With a bedroom above each lower room, the house is bisected by a steep, narrow staircase. A kitchen was to the rear. Right up to the 1980s it wasn't uncommon for the original outside toilet (to the rear of the kitchen) to still be present, and some houses still had no bathroom or central heating.

The layout of the streets which contain these terraces are typical of the area and consist of grid layouts intersected with wide back entries which run the length of the terrace blocks at the rear and at each end of the block. This alley/back-entry layout is supposed to be because of an old by-law of the Levenshulme local authority that every terraced house had to have a front garden and allow access to the back door by a horse and cart to enable rubbish to be removed without the need enter the house.[11]

These back entries are now generally considered to be a threat to home security. Accordingly Manchester City Council has, over recent years, helped residents by funding a "gated alley" response to the threat. When the majority of affected residents of a particular entry are in agreement the entries have iron gates set up at all ingress and egress points with all affected residents being issued a key.[12]

Governance

Manchester and its districts had developed into what were referred to as the "Thirty Townships". Levenshulme was one of them and in 1865 got its own 'board' which shortly thereafter developed into an urban district council. Prior to the turn of the 20th century West Levenshulme was considered to be a "dormitory" for Manchester. This description eventually changed to one of "residential suburb" a decade or so later, but East Levenshulme was still primarily industrial in nature consisting mostly of print works, bleach works, dye works and mattress works. In spite of the preponderance of industrial works there were also several farms, and the area around what is now Levenshulme High School was considered to be semi-rural until the 1920s.[4]

Until the late 19th century Manchester's outlying townships had to supply their own amenities. This was becoming increasingly difficult for the urban councils to do and as a result there was a considerable difference in prices charged to the residents compared to the prices charged by Manchester itself. Manchester refused to alleviate these difficulties unless townships agreed to come under its control. As a result the townships slowly began to amalgamate into Manchester's rule. Along with Withington, Levenshulme protested at the discrepancy of prices for gas in the city and for the outlying townships that were already supplied by Manchester. Nevertheless many of those townships arranged to get their electricity from Manchester, possibly in the hope that they would benefit from the city's plans to electrify the tram system when the existing lease with the Manchester Carriage and Tramways Company was due to end in 1901. Along with Gorton, Levenshulme joined Manchester in 1909. The tramways were extended to serve Levenshulme before the start of the First World War in 1914.[4]

The ward boundaries of Levenshulme have been moved in recent ward reorganisations, and as a result large areas in the north and east of Levenshulme are now officially in the ward of Gorton South, to the confusion and irritation of local residents. To the west areas historically regarded as Fallowfield are now officially part of Levenshulme and Rusholme. The Levenshulme ward is represented in Manchester City Council by Dzidra Noor, Basat Sheikh and Nasrin Ali (Labour).

Levenshulme forms part of the wider Manchester Gorton Parliamentary constituency and is represented by Sir Gerald Kaufman MP (Labour), who has held the seat since 1983.

Demography

In 1830 Levenshulme had a population of 768.[13]

In 2001 Levenshulme had an Irish population of approximately 7.0% which was twice the Manchester average,[14] and as a consequence it was sometimes called 'County Levenshulme' in reference to the county structure in Ireland, though the 2011 census figures show the Irish population has shrunk to 4.1%.[15] The demographics within the district have changed with increasing numbers of (mostly Muslim) people of South Asian origin and an ever increasing number of Africans, have settled in Levenshulme. Over a third of the population belong to an ethnic minority. In recent times Levenshulme has also seen an influx of Eastern Europeans moving into the area, bringing about Polish confectionery shops. Many students also rent accommodation in the area.

In the 2001 Census, the ethnic make up of Levenshulme was:[16]

| Ethnic group | Person count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White: British | 8,625 | 65.12 |

| Asian/Asian-British: Pakistani | 1,714 | 13.51 |

| White: Irish | 884 | 6.97 |

| White: Other | 301 | 2.37 |

| Black/Black-British: Caribbean | 300 | 2.36 |

| Asian/Asian-British: Indian | 185 | 1.46 |

| Asian/Asian-British: Other Asian | 161 | 1.27 |

| Mixed: White & Black Caribbean | 149 | 1.17 |

| Asian/Asian-British: Bangladeshi | 139 | 1.10 |

| Black/Black-British: African | 135 | 1.06 |

| Chinese | 110 | 0.87 |

| Mixed: White & Asian | 94 | 0.74 |

| Mixed: White & Black African | 77 | 0.61 |

| Other Ethnic Groups | 77 | 0.61 |

| Mixed: Other | 61 | 0.48 |

| Black/Black-British: Other Black | 39 | 0.31 |

Culture

Levenshulme is evolving into an area typical of South Manchester, i.e. a mix of pubs, bars, restaurants, takeaways, solicitors, pound shops and booking agents along with terraced housing. The area is one of the newly gentrified areas of South Manchester and neighbours Heaton Chapel to the south which is one of the most affluent parts of Greater Manchester.[17]

Levenshulme Market was launched in March 2013 and operates every Saturday (between March and December) from 10am to 4pm. It is a social enterprise run market which prides itself on its diverse range of high quality traders. It has a changing roster of 50 artisan traders selling produce, street food, plants, gifts, vintage clothing and homeware.

Since 1998, the annual "Levenshulme Festival" usually features 120+ multi-cultural events from firework displays to music concerts.[18]

The community radio station All FM is based in Levenshulme.

There is a local amateur dramatic society, Levenshulme Players who have produced stage plays, comedy reviews, Murder Mystery Evenings and radio plays for All FM. They write much of their own material.

Love Levenshulme is a hyper-local community blog which features local businesses, events and shares positive news within the Levenshulme vicinity.

Religion

Statistics

Levenshulme has a varied ethnic mix. According to the 2011 Census the breakdown by religion is:[19]

Places of worship

| Name | Address | Religion | Year built/Established |

|---|---|---|---|

| St Aidan's Orthodox Church | Clare Road | English Language Orthodox | |

| St Andrew's Church | Broom Avenue | Church of England | |

| Levenshulme Baptist Church | Elmsworth Avenue | Baptist | |

| Levenshulme Methodist Church | Stockport Road | Methodist | 13 May 1865 |

|

Methodism in Levenshulme has a history dating back to 1766 (based on financial records of the Methodist Society). In that time there have been five Methodist churches. Levenshulme Methodist Church (formerly Levenshulme New Wesleyan Chapel) is the only one to survive.[20] | |||

| Levenshulme Inspire / Levenshulme United Reformed Church | Stockport Road | URC | |

| The church has now been completely modernised, the building being the centre for Levenshulme Inspire, housing flats, cafes, shops and a community meeting space | |||

| Madina Mosque & UK Islamic Mission | Barlow Road | Muslim | Islamic Centre opened c.1986 |

|

The Islamic Centre is housed in the building which was originally St Peter's School built in 1854 and closed in 1982.[21] | |||

| St Mark's Church | Barlow Road | Church of England | Built 1908 |

|

St Mark's was declared a Grade II listed building on 6 June 1994.[22] | |||

| St Mary of the Angels & St. Clare RC Church | Elbow Street | Roman Catholic | |

| St Peter's Church | Stockport Road | Church of England | Consecrated in 1860 |

|

In 1852 a donation of 1,445 square yards of land and £500 was made to Levenshulme to build a church. The donation came from a member of a family known for generous donations for churches, Charles Carill-Worsley. St Peter's School (directly behind the church) was built in 1854 and was used initially as a temporary place for the congregation to worship.[21] | |||

St Mark's Church

St Mark's Church Madina Mosque & UK Islamic Mission

Madina Mosque & UK Islamic Mission St Peter's Church

St Peter's Church

Recreation and leisure

Parks

Green Bank Fields

This park is a green area stretching between Manor Road in the north, Mount Road in the east and Barlow Road in the south and west. It is primarily open grassland but also houses an open-air, enclosed 5-a-side football pitch adjacent to the Mount Road exit.

Until about 1920 the land that Green Bank Fields was on held a dairy farm called Green Bank Farm (Wolfenden's) and a small house called Botany Bay Cottage. The entrance to the farm was originally where the main entrance to the park is now on Barlow Road adjacent to Byrom Parade shops.[21]

Manchester City Council fomented a local controversy by selling off part of Mellands (GMPTE) Playing Fields, Gorton to Dappa Homes to build 149 houses. Dappa is obliged to replace the land they are using to build the homes. In May 2004 Dappa Homes submitted plans to build 3 football pitches, a clubhouse and surround the park with a 10 foot fence on Green Bank Fields. This would have had the effect of reducing the versatile open-space into a restricted use site. The plans were later withdrawn by Dappa.[23]

Highfield Country Park

Highfield Country Park

Highfield Country Park is a 70-acre (280,000 m2) area of open land that stretches to the east of Broom Avenue across to the back of Reddish Golf Course and over to the junction of Longford Road and Nelstrop Road.[24]

In the 1970s it was designated as a country park by the council, but at the time it wasn't much more than a landfill site that was formerly the site of the UCP tripe factory, Jackson's Brickworks, Levenshulme Dye and Bleach Works and High Field Farm. The claypit formed by the extracted clay for the brickworks was much used by local children as a play area, known as "the Brickie".

Until 2004 the park was jointly maintained by Manchester City Council and a group of volunteers called the 'Friends of Highfield Park'. In July 2004 the park came to the attention of the Prudential Grass Roots campaign (run by the BTCV conservation charity). Over a 12-month period the park was transformed from a dreary, vandalised wasteland into a pleasant country park with a picnic area and mapped out country walks.[25]

Nutsford Vale Country Park

Nutsford Vale is a formally declared 'open space' ensuring that it remains green space, and that it does not suffer from adverse building development. The area is a local oasis for bird life, insects and other wildlife, made up of rough grassland and a wide variety of trees, providing a home for a variety of plants and animal species.

The Friends of Nutsford Vale and a committee provide a management and maintenance plan for the site.

There are various access points with the main entrances located at the end of Bickerdike Avenue M12 5SZ and on Matthews Lane M19 3DS.

Sport

Swimming

Levenshulme Swimming Baths was built in the late 19th century and was formerly called "Levenshulme Public Baths and Washhouse" as it also housed the public washhouse at the side.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s Levenshulme Baths was used as a training pool for Longsight resident Sunny Lowry, who, in 1933, was the first British woman to swim the English Channel (from France to England).[26]

Arcadia Sports Centre

Located on Yew Tree Avenue, this sports facility was formerly home to Manchester Roller Hockey Club and affectionately known to locals as "the Shed".

On 20 February 2016, the new Arcadia Leisure Centre opened on the site of the old sports hall.[27]

Community

Library

Levenshulme Library is a "Carnegie library" as it was gifted to the people of Levenshulme by industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. The ceremonial laying of the first brick (in reality an engraved stone plaque) took place on 5 December 1903. The stone was laid by George Paulson in his role as Chairman of the Free Library Committee. The library actually opened its doors to the public in 1904. At the time the money was gifted there was a minor local furore as some Levenshulme residents expressed the opinion that it was "immoral" for the then urban district council to accept the money from Carnegie as they believed the money to be "tainted". This was allegedly due to Carnegie's suppression of trade unions in the United States.[21]

In 2012 proposals were put forward by Manchester Council to replace the library by a new building shared with the replacement for the swimming pools. In 2013 these proposals were amended to close both library and pools immediately and to only provide a reduced "book drop-off" service. These proposals were strongly contested by local groups and the building was symbolically taken over for a 24-hour "read-in" as a protest.

In February 2016, Levenshulme Library closed and was replaced by the new Arcadia Library and Leisure Centre on Stockport Road.[28]

Education

| Name | Address | Info |

|---|---|---|

| Primary schools | ||

| Alma Park Primary School | Errwood Road | |

| Chapel Street Primary School | Chapel Street | |

| St Andrew's Church of England Primary School | Broom Avenue | |

| St Mary's Roman Catholic Primary School | Clare Road | |

| Secondary schools | ||

| Levenshulme High School | Crossley Road | |

Tourism

"The street with no name"

Levenshulme is not the place one would regard as a centre of tourism but due to several reports in both local and national newspapers and on several internet blogs there now seems to be a trickle of tourists making visits to Levenshulme railway station since the 'news' broke of "The Street with No Name".[29]

The street that the railway station is located on is 160 years old and 77 yards long yet has no official name and never has had one. In May 2007 as a benefit of a £5,000 grant awarded to the 'Friends of Levenshulme Station' by the Awards For All lottery grants scheme, an unofficial road sign was erected at the entrance to the street. The sign gave the name of the street as "The Street With No Name". According to local residents the street had been informally called this for years and it seemed appropriate that it now had a sign so people could find it. The first sign was fitted approximately three feet from the ground and was stolen a short time later. The replacement was refitted 12 feet (3.7 m) above the road so as to discourage would-be thieves.

Notable people

- Ernest Marples, a Conservative politician, was born and brought up in Levenshulme. Served as the Minister of Transport in the Harold Macmillan and Alec Douglas-Home governments and was elevated to the peerage in 1974.

- The architect Norman Foster was brought up in Levenshulme.[30]

- Dad's Army's "Captain Mainwaring", Arthur Lowe attended Chapel Street School.

- Beryl Reid, the comedian, grew up in Manchester where she attended Withington and Levenshulme High Schools.

- Actor Graeme Hawley who plays John Stape in Coronation Street is a resident.[31]

- Professor Terry Callaghan,[32] who was a member of the Lead Authors of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007, together with Al Gore. He was brought up in Levenshulme and went to Chapel Street School and Burnage Grammar School. At 14 he struck up a friendship with Alec Cowan, (Councillor, Levenshulme Ward 2004–2010) and the two have remained friends ever since.

- Drummer Tony McCarroll formerly of Oasis

- Harry Hancock, a professional footballer, was born in Levenshulme

See also

References

- ↑ "2011 Census Levenshulme dashboard". Manchester City Council. Retrieved 2014-07-23.

- ↑ http://manchesterhistory.net/LONGSIGHT/HISTORY/history.html

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-04. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- 1 2 3 Levenshulme Local History: Levenshulme High School Diamond Jubilee publication, 1989 ISBN E000043855

- 1 2 "Looking back at Levenshulme and Burnage" Willow Publishing 1987 ISBN 0-946361-22-3, page 4.

- ↑ "Looking back at Levenshulme and Burnage" Willow Publishing 1987 ISBN 0-946361-22-3, page 5/6.

- ↑ "1848 maps". Old-maps.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ↑ "Looking back at Levenshulme and Burnage" Willow Publishing 1987 ISBN 0-946361-22-3, page 29.

- ↑ "Looking back at Levenshulme and Burnage" Willow Publishing 1987 ISBN 0-946361-22-3, page 31.

- ↑ "Townships - Levenshulme | A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 4 (pp. 309-310)". British-history.ac.uk. 2003-06-22. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ↑ "Looking back at Levenshulme and Burnage" Willow Publishing 1987 ISBN 0-946361-22-3, page 6.

- ↑ "Alleys and alleygating". Manchester City Council.

- ↑ "Historical and Genealogical Information for the Region Anciently Known as the Salford Hundred". Mancuniensis.info. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ↑ Neighbourhood Statistics. "National Statistics - Neighbourhood Statistics for Levenshulme ward". Neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ↑ "Ethnic Breakdown in Levenshulme 2011 Census Data".

- ↑ "Neighbourhood Statistics: Levenshulme (Ward) by Ethnicity". National Statistics. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ http://www.bestkeptstations.org.uk/place/heaton-chapel/

- ↑ "Levenshulme Festival 2007 web page". Levenshulmefestival.co.uk. 2006-10-16. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ↑ "Neighbourhood Statistics: Levenshulme (Ward) by Religion". National Statistics. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Armitage, Rita (1997). Methodism in Levenshulme: The first 200 years. John Malam & Hilary Malam. p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Sussex, Gay; Peter Helm; Andrew Brown (1987). Looking Back at Levenshulme & Burnage. Looking Back at... Willow Publishing. ISBN 0-946361-22-3.

- ↑ "A-Z of Listed Buildings in Manchester". Manchester City Council web pages. Manchester City Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "Planning application for Green Bank Fields revised layout". GMC Public Access website. 2006-04-12. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ "Highfield Country Park". Friends of Highfield Country Park. 2008-11-23. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ↑ "Case Study: Highfield Country Park, Manchester" (PDF). BTCV Grass Roots. 2005-09-07. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Kate Stirrup (2003-01-16). "Bath to the future". column. South Manchester Reporter. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ "Arcadia Library and Leisure Centre". Manchester City Council. Manchester City Council. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ↑ "Arcadia Library and Leisure Centre". Manchester City Council. Manchester City Council. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ↑ Nick Towle (2007-05-17). "Move over Clint, it's... The Street With No Name". column. South Manchester Reporter. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ↑ "Norman Foster - the man behind the 'glass egg'". BBC. 2005. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ↑ Kelly, Angela (2009-02-11). "Why Graeme's on a roll". Macclesfield Express. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ↑ "Prof Terry Callaghan".

External links

- Levenshulme then and now: A personal view

- Levenshulme Festival website

- Levenshulme Community Association

- Levenshulme Churches

- Manchester City Council: Image library, containing 1420 images of Levenshulme (as of September 2007)