Mehmed III

| Mehmed III محمد ثالث | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caliph of Islam Amir al-Mu'minin Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques | |||||

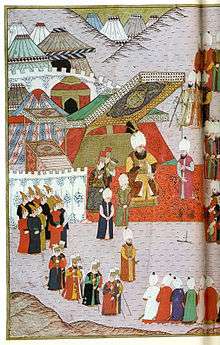

The portrait of Sultan Mehmet III by Italian painter Cristofano dell'Altissimo, 16th century. | |||||

| 13th Ottoman Sultan (Emperor) | |||||

| Reign | January 15, 1595 – December 22, 1603 | ||||

| Predecessor | Murad III | ||||

| Successor | Ahmed I | ||||

| Born |

May 26, 1566 Manisa, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Died |

December 21/22, 1603 (aged 37) Constantinople, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Consorts |

Handan Sultan Valide Sultan of Mustafa I and 3 others | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | House of Osman | ||||

| Father | Murad III | ||||

| Mother | Safiye Sultan | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Tughra |

| ||||

Mehmed III (Ottoman Turkish: محمد ثالث, Meḥmed-i sālis; Turkish: III. Mehmet; May 26, 1566 – December 21/22, 1603) was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1595 until his death in 1603.

Early life

He was born at the Manisa Palace, during the reign of his great-grandfather, Suleiman the Magnificent, in 1566. He was the son of Şehzade Murad (later Murad III), himself the son of Şehzade Selim (later Selim II), who was the son of Sultan Suleiman and Hürrem Sultan. His mother was Safiye Sultan, said to have been Albanian from the Dukagjin highlands.[1] His great-grandfather died the year he was born and his grandfather became the new Sultan, Selim II. His grandfather Sultan Selim II died when Mehmed was 8 and Mehmed's father, Murad III, became Sultan in 1574. Mehmed thus became Crown Prince until his father's death in 1595, when he was 28 years old.

Reign

Power struggle in Constantinople

Mehmed III remains notorious even in Ottoman history for having nineteen of his brothers and half-brothers executed to secure power.[2] They were all strangled by his deaf-mutes.

Mehmed III was an idle ruler, leaving government to his mother Safiye Sultan, the valide sultan.[3] His first major problem was the rivalry between two of his viziers, Serdar Ferhad Pasha and Koca Sinan Pasha, and their supporters. His mother and her son-in-law Damat Ibrahim Pasha supported Koca Sinan Pasha, and prevented Mehmed III from taking control of the issue himself. The issue grew to cause major disturbances by janissaries. On 7 July 1595, Mehmed III finally sacked Serdar Ferhad Pasha from the position of Grand Vizier due to his failure in Wallachia and replaced him with Sinan.[4]

Austro-Hungarian War

The major event of his reign was the Austro-Ottoman War in Hungary (1593–1606). Ottoman defeats in the war caused Mehmed III to take personal command of the army, the first sultan to do so since Suleiman I in 1566. Accompanied by the Sultan, the Ottomans conquered Eger in 1596. Upon hearing of the Habsburg army's approach, Mehmed wanted to dismiss the army and return to Istanbul.[5] However, the Ottomans eventually decided to face the enemy and defeated the Habsburg and Transylvanian forces at the Battle of Keresztes[6] (known in Turkish as the Battle of Haçova), during which the Sultan had to be dissuaded from fleeing the field halfway through the battle. Upon returning to Istanbul in victory, Mehmed told his Vezirs that he would campaign again.[7] The next year the Venetian Bailo in Istanbul noted, "the doctors declared that the Sultan cannot leave for war on account of his bad health, produced by excesses of eating and drinking".[8]

In reward for his services at the war, Cigalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha was made Grand Vizier in 1596. However, with pressure from the court and his mother, Mehmed reinstated Damat Ibrahim Pasha to this position shortly afterwards.[4]

However, the victory at the Battle of Keresztes was soon set back by some important losses, including the loss of Győr (Turkish: Yanıkkale) to the Austrians and the defeat of the Ottoman forces led by Hafız Ahmet Pasha by the Wallachian forces under Michael the Brave in Nikopol in 1599. In 1600, Ottoman forces under Tiryaki Hasan Pasha captured Nagykanizsa after a 40-day siege and later successfully held it against a much greater attacking force in the Siege of Nagykanizsa.[9]

Jelali revolts

Another major event of his reign was the Jelali revolts in Anatolia. Karayazıcı Abdülhalim, a former Ottoman official, captured the city of Urfa and declared himself sultan in 1600. The rumors of his claim to the throne spread to Constantinople and Mehmed ordered the rebels to be treated harshly to dispel the rumors, among these was the execution of Hüseyin Pasha, whom Karayazıcı Abdülhalim styled as Grand Vizier. In 1601, Abdülhalim fled to the vicinity of Samsun after being defeated by the forces under Sokulluzade Hasan Pasha, the governor of Baghdad. However, his brother, Deli Hasan, killed Sokulluzade Hasan Pasha and defeated troops under the command of Hadım Hüsrev Pasha. He then marched on to Kütahya, captured and burned the city.[4][9]

Relationship with England

In 1599, the fourth year of Mehmed III's reign, Queen Elizabeth I sent a convoy of gifts to the Ottoman court. These gifts were originally intended for the sultan's predecessor, Murad III, who had died before they had arrived. Included in these gifts was a large jewel-studded clockwork organ that was assembled on the slope of the Royal Private Garden by a team of engineers including Thomas Dallam. The organ took many weeks to complete and featured dancing sculptures such as a flock of blackbirds that sung and shook their wings at the end of the music.[10][11] The musical clock organ was destroyed by the succeeding Sultan Ahmed I. Also among the English gifts was a ceremonial coach, accompanied by a letter from the Queen to Mehmed's mother, Safiye Sultan. These gifts were intended to cement relations between the two countries, building on the trade agreement signed in 1581 that gave English merchants priority in the Ottoman region.[12] Under the looming threat of Spanish military presence, England was eager to secure an alliance with the Ottomans, the two nations together having the capability to divide the power. Elizabeth's gifts arrived in a large 27-gun merchantman ship that Mehmed personally inspected, a clear display of English maritime strength that would prompt him to build up his fleet over the following years of his reign. The Anglo-Ottoman alliance would never see consummation, however, with relations between the nations growing stagnant due to anti-European sentiments reaped from the worsening Austro-Ottoman War and the deaths of Safiye Sultan's interpreter and the pro-English chief Hasan Pasha.[12][13]

Death

He died on 22 December 1603 at the age of 37. The cause is unknown, but natural causes or disease are most likely. He was buried in Hagia Sophia.

Family

- Consorts

Mehmed had six known consorts. None of them bore the title haseki sultan.[14]

- an Abkhazian woman, called Halime Sultan in the TV drama Muhteşem Yüzyıl: Kösem, mother of Mustafa I;

- Handan Sultan;

- Mother of Prince Mahmud (killed 1603; buried in Şehzade Mehmed Mosque);

- Mother of Prince Selim (died 1597, during the outbreak of plague);[15]

- Mother of Prince Cihangir;

- Princess Helena Komnenós.

- Sons

- Şehzade Sultan Mahmud (1584 – 7 June 1603, buried in Şehzade Mahmud Mausoleum, Şehzadebaşi Mosque), became Heir Apparent on 15 January 1595;

- Şehzade Sultan Selim[16] (1585 - 20 April 1597, buried in Hagia Sophia);

- Şehzade Sultan Yahya (1585 – Montenegro, 1649);

- Sultan Ahmed I (18 April 1589 – 22 November 1617), with Handan;

- Sultan Mustafa I (1591 – 20 January 1639, buried in Mustafa I Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia);

- Şehzade Sultan Cihangir (died in infancy).[17]

- Daughters

- a daughter (whose name is lost) from the mother of Mustafa I, married to Kara Davud Pasha, Grand Vizier;

- another daughter, married to Damad Ali Pasha, Vizier.

References

- ↑ Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 94. ISBN 0-19-507673-7.

Murad's favorite was Safiye, a concubine said to be of Albanian origin from the village of Rezi in the Ducagini mountains.

- ↑ Quataert, Donald. The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922, p.90. Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-521-63328-1

- ↑ Kinross, p.288

- 1 2 3 "Mehmed III". İslam Ansiklopedisi. 28. Türk Diyanet Vakfı. 2003. pp. 407–413.

- ↑ Karateke, Hakan T. "On the Tranquility and Repose of the Sultan." The Ottoman World. Ed. Christine Woodhead. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2011. p. 120.

- ↑ Finkel, Caroline. Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, p.175. Basic Books, 2005. ISBN 0-465-02396-7

- ↑ Karateke, p. 122.

- ↑ Goodwin, Jason. Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire, p.166. New York: Henry Holt & Company.

- 1 2 "Mehmed III". Büyük Larousse. 15. Milliyet Newspaper Press. pp. 7927–8.

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel (2004-05-02). "How fear turned to fascination". London: telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ↑ Jean Giullou: Die Orgel. Erinnerung und Vision.Christoph Glatter-Götz 1984 p. 35 with image

- 1 2 "An eye for detail". BBC News. December 21, 2007.

- ↑

- ↑ Peirce (1993) p.104

- ↑ Disease and Empire: A History of Plague Epidemics in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire (1453--1600). ProQuest. 2008. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-549-74445-0.

- ↑ Öztuna, Yılmaz (2005). Devletler ve Hanedanlar. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Yayınlar. p. 176. ISBN 9789751707918.

- ↑ "The Imperial House of Osman GENEALOGY". 2 May 2006. Archived from the original on May 2, 2006.

External links

![]() Media related to Mehmed III at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mehmed III at Wikimedia Commons

| Mehmed III Born: May 26, 1566 Died: December 22, 1603[aged 37] | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Murad III |

Sultan of the Ottoman Empire January 15, 1595 – December 22, 1603 |

Succeeded by Ahmed I |

| Sunni Islam titles | ||

| Preceded by Murad III |

Caliph of Islam January 15, 1595 – December 22, 1603 |

Succeeded by Ahmed I |