New Zealand Railways Department

| Reporting mark | NZGR |

|---|---|

| Locale | New Zealand |

| Dates of operation | 1880–1981 |

| Predecessor |

Public Works Department (rail operations, acquired 1880) Port Chalmers Railway Company (acquired 1880) Waimea Plains Railway (acquired 1886) Thames Valley and Rotorua Railway Company (acquired 1886) New Zealand Midland Railway Company (acquired 1891) Wellington and Manawatu Railway Company (acquired 1908) |

| Successor | New Zealand Railways Corporation |

| Track gauge | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) |

| Length |

1,828 km (1,136 mi) (1880) 5,696 km (3,539 mi) (1952, peak) 4,799 km (2,982 mi) (1981) |

| Headquarters | Wellington |

The New Zealand Railways Department, NZR or NZGR (New Zealand Government Railways) and often known as the "Railways", was a government department charged with owning and maintaining New Zealand's railway infrastructure and operating the railway system.[1] The Department was created in 1880 and was corporatised on 1 April 1982 into the New Zealand Railways Corporation.[2] Originally, railway construction and operation took place under the auspices of the former provincial governments and some private railways, before all of the provincial operations came under the central Public Works Department. The role of operating the rail network was subsequently separated from that of the network's construction. From 1895 to 1993 there was a responsible Minister, the Minister of Railways. He was often also the Minister of Public Works.

History

Originally, New Zealand's railways were constructed by provincial governments and private firms. The largest provincial operation was the Canterbury Provincial Railways, which opened the first public railway at Ferrymead on 1 December 1863. Following the abolition of the provinces in 1877, the Public Works Department took over the various provincial railways. However, since the Public Works Department was charged with constructing new railway lines (among other public works) the day to day railway operations were transferred into a new government department on the recommendation of a parliamentary select committee.[3] At the time 1,828 kilometres (1,136 miles) of railway lines were open for traffic, 546 km (339 mi) in the North Island and 1,283 km (797 mi) in the South Island, mainly consisting of the 630 km (390 mi) Main South Line from the port of Lyttelton to Bluff.[4]

Formation and early years

The Railways Department was formed in 1880 during the premiership of Sir John Hall. That year, the private Port Chalmers Railway Company Limited was acquired by the department and new workshops at Addington opened. Ironically, the first few years of NZR were marked by the Long Depression, which led to great financial constraint on the department.[5] As a result, the central government passed legislation to allow for the construction of more private railways. A Royal Commission, ordered by Hall, had removed plans for a railway line on the west coast of the North Island from Foxton to Wellington. Instead, in August 1881 the Railways Construction and Land Act was passed, allowing joint-stock companies to build and run private railways, as long as they were built to the government's standard rail gauge of 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) and connected with the government railway lines. The Act had the effect of authorising the Wellington and Manawatu Railway Company to build the Wellington-Manawatu Line.[6]

The most important construction project for NZR at this time was the central section of the North Island Main Trunk. Starting from Te Awamutu on 15 April 1885, the section - including the famous Raurimu Spiral - was not completed for another 23 years.[7]

The economy gradually improved and in 1895 the Liberal Government of Premier Richard Seddon appointed Alfred Cadman as the first Minister of Railways. The Minister appointed a General Manager for the railways, keeping the operation under tight political control.[8] Apart from four periods of government-appointed commissions (1889–1894, 1924–1928, 1931–1936 and 1953–1957), this system remained in place until the department was corporatised in 1982.[8] In 1895, patronage had reached 3.9M passengers per annum and 2.048M tonnes.[9]

NZR produced its first New Zealand-built steam locomotive, W class, in 1889.

Along with opening new lines, NZR began acquiring a number of the private railways which had built railway lines around the country. In 1886 the Waimea Plains Railway Company acquired. At the same time, a protracted legal battle with New Zealand Midland Railway Company began, and was only resolved in 1898. The partially completed Midland line was not handed over to NZR until 1900.[10] By that time, 3,200 km (2,000 mi) of railway lines were open for traffic.[4] The acquisition in 1908 of the Wellington and Manawatu Railway Company and its railway line marked the completion of the North Island Main Trunk from Wellington to Auckland. A new locomotive class, the X class, was introduced in 1909 for traffic on the line. The X class was the most powerful locomotive at the time. Gold rushes led to the construction of the Thames Branch, opening in 1898.

In 1906 the Dunedin Railway Station was completed, architect George Troup. A. L. Beattie became Chief Mechanical Officer in April 1900. Beattie designed the famous A class, the first "Pacific" class in the world, and many other locomotive classes.[11]

The first bus operation by NZR began on 1 October 1907, between Culverden on the Waiau Branch and Waiau Ferry in Canterbury. By the 1920s NZR was noticing a considerable downturn in rail passenger traffic on many lines due to increasing ownership of private cars, and from 1923 it began to co-ordinate rail passenger services with private bus services. The New Zealand Railways Road Services branch was formed to operate bus services.

By 1912, patronage had reached 13.4M passengers per annum (a 242% increase since 1895) and 5.9M tonnes of freight (a 188% increase since 1895).[9]

World War I

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 had a significant impact on the Railways Department. That year the Aa class appeared, and the following year the first AB class locomotives were introduced. This class went on to become the most numerous locomotive class in New Zealand history, with several examples surviving into preservation.

The war itself led to a decline in passenger, freight and train miles run but also led to an increase in profitability. In the 1917 Annual Report, a record 5.3% return on investment was made.[12] The war did take its toll on railway services, with dining cars being removed from passenger trains in 1917, replaced by less labour-intensive refreshment rooms at railway stations along the way. As a result, the "scramble for pie and tea at Taihape" became a part of New Zealand folklore.[12]

Non-essential rail services were curtailed as more staff took part in the war effort, and railway workshops were converted for producing military equipment, on top of their existing maintenance and construction work.[12] The war soon affected the supply of coal to the railways. Although hostilities ended in 1918, the coal shortage carried on into 1919 as first miners strikes and then an influenza epidemic cut supplies. As a result, non-essential services remained in effect until the end of 1919. Shortages of spare parts and materials led to severe inflation, and repairs on locomotives being deferred.

Increasing competition and great depression

In 1920 the 3,000-mile (4,800 km) milestone of open railway lines was reached and 15 million passengers were carried by the department.[13] The first of the now iconic railway houses were prefabricated in a factory in Frankton for NZR staff. However, this scheme was shut down in 1929 as it was considered improper for a government department to compete with private builders.[13]

The Otira Tunnel was completed in 1923, heralding the completion of the Midland Line in the South Island. The tunnel included the first section of railway electrification in New Zealand and its first electric locomotives, the original EO class. The section was electrified at 1,500 V DC, due to the steep grade in the tunnel, and included its own hydro-electric power station.[14] The second section to be electrified by the department was the Lyttelton Line in Christchurch, completed in 1929, at the same voltage and current. This again saw English Electric supply locomotives, the EC class.

In the same year, Gordon Coates became the Minister of Railways. Coates was an ambitious politician who had an almost "religious zeal" for his portfolio. During the summer of 1923, he spent the entire parliamentary recess inspecting the department's operations. The following year, he put forward a "Programme of Improvements and New Works'".[15]

Coates scheme proposed spending £8 million over 8 years. This was later expanded to £10 million over 10 years. The programme included:

- The Auckland - Westfield deviation of the North Island Main Trunk;

- New marshaling yards at Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch;

- The Milson Deviation of the North Island Main Trunk through Palmerston North;

- The Rimutaka Tunnel under the Rimutaka Ranges in Wellington;

- The Tawa Flat deviation of the North Island Main Trunk out of Wellington;

- Electric lighting;

- New locomotive facilities and

- New signaling systems.

An independent commission, led by Sir Sam Fay and Sir Vincent Raven produced a report known as the "Fay Raven Report"[16] which gave qualified approval to Coates' programme. The reports only significant change was the proposal of a Cook Strait train ferry service between Wellington and Picton, to link the two systems up.[17] Coates went on to become Prime Minister in 1925, an office he held until 1928 when he was defeated at the general election of that year. While the Westfield and Tawa Flat deviations proceeded, the Milson deviation and Rimutaka Tunnel projects remained stalled. The onset of the Great Depression from late 1929 saw these projects scaled back or abandoned. The Westfield deviation was completed in 1930 and the Tawa deviation proceeded at a snail's pace. A number of new lines under construction were casualties, including the Rotorua-Taupo line, approved in July 1928 but abandoned almost a year later due to the depression.[18] An exception was the Stratford–Okahukura Line, finished in 1933.[19]

However, there was criticism that maintenance was being neglected. In the Liberals last year of office in 1912, 140 miles (230 km) of line had been relaid, but that was reduced to 118 in 1913, 104 in 1914, 81 in 1924 and 68 in 1925, during the Reform Government's years.[20]

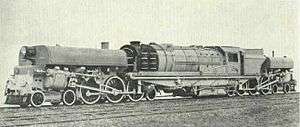

Once again, growing traffic requirements led to the introduction of a new type of locomotive, the ill-fated G class Garratt locomotives in 1928. Four of the locomotives were introduced for operation on the North Island Main Trunk. They were not well suited to New Zealand conditions: they had overly complex valve gear, were too hot for crews manning them and too powerful for the wagons they were hauling.[21] The failure of this class lead to the introduction of the K class in 1932.

Tough economic conditions and increasing competition from road transport led to calls for regulation of the land transport sector. In 1931 it was claimed half a million tons of freight had been lost to road transport.[22] That year, the department carried 7.2 million passengers per year, down from 14.2 million in 1923.[18] In 1930 a Royal Commission on Railways recommended that transport be "co-ordinated" and the following year parliament passed the Transport Licensing Act 1931. The Act regulated the carriage of goods and entrenched the monopoly the department had on land transport. It set a minimum distance road transport operators could transport goods at 30 miles (48 km) before they had to be licensed. The Act was repealed in 1982.[23]

In 1933 plans for a new railway station and head office in Wellington were approved, along with the electrification of the Johnsonville Line (then still part of the North Island Main Trunk). The Wellington Railway Station and Tawa flat deviation were both completed in 1937.[24] As part of attempts by NZR to win back passengers from private motor vehicles, the same year the first 56-foot carriages were introduced.

Garnet Hercules Mackley was appointed General Manager in 1933, and worked hard to improve the standard and range of services provided by the Department. This included a number of steps to make passenger trains faster, more efficient and cheaper to run. In the early 20th century, NZR had begun investigating railcar technology to provide passenger services on regional routes and rural branch lines where carriage trains were not economic and "mixed" trains (passenger carriages attached to freight trains) were undesirably slow. However, due to New Zealand's rugged terrain overseas technology could not simply be directly introduced. A number of experimental railcars and railbuses were developed. From 1925 these included the Leyland experimental petrol railcar and a fleet of Model T Ford railbuses, the Sentinel-Cammell steam railcar and from 1926 the Clayton steam railcar and successful Edison battery-electric railcar. 10 years later in 1936 the Leyland diesel railbus was introduced, but the first truly successful railcar class to enter service began operating that year, the Wairarapa railcar especially designed to operate over the Rimutaka Incline. This class followed the building of the Red Terror (an inspection car on a Leyland Cub chassis) for the General Manager Garnet Mackley in 1933. More classes followed over the years, primarily to operate regional services.

Following the success of the Wairarapa railcar class, in 1938 the Standard class railcars were introduced. A further improvement to passenger transport came in July that year, with electric services on the Johnsonville Line starting with the introduction of the DM/D English Electric Multiple Units.[25]

Three new locomotive classes appeared in 1939: the KA class, KB class and the J class. The KA was a further development of the K class, while the J class was primarily for lighter trackage in the South Island. The numerically smaller KB class were allocated to the Midland line, where they dominated traffic. This led to the coining of the phrase "KB country" to describe the area, made famous by the National Film Unit's documentary of the same title.

By 1954 the network exceeded 5,600 km (3,500 mi), 60% of it on gradients between 1 in 100 and 1 in 200 and 33% steeper than 1 in 100.[26]

Branches

The Railways Department followed a traditional 'branch' structure, which was carried over to the Corporation.

- Commercial;

- Finance and Accounts;

- Mechanical;

- Publicity and Advertising;

- Refreshment;

- Railways Road Services;

- Stores;

- Traffic; and

- Way and Works.

Performance

The table below records the performance of the Railways Department in terms of freight tonnage:[27]

| Year | Tonnes (000s) | Net tonne-km (millions) |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 11,300 | 2,980 |

| 1973 | 12,100 | 3,305 |

| 1974 | 13,200 | 3,819 |

| 1975 | 12,900 | 3,695 |

| 1976 | 13,200 | 3,803 |

| 1977 | 13,600 | 4,058.9 |

| 1978 | 12,600 | 3,824 |

| 1979 | 11,700 | 3,693 |

| 1980 | 11,800 | 3,608 |

| 1981 | 11,400 | 3,619 |

| 1982 | 11,500 | 3,738.9 |

Workshops

The following NZR workshops were builders of locomotives:

- Hutt Workshops, Lower Hutt, at Petone to 1929

- Hillside Workshops, Dunedin, now Hillside Engineering

- Addington Workshops, Christchurch (closed 1990)

- East Town Workshops, Wanganui (closed 1986) also Aramoho

- Newmarket Workshops, Auckland (opened 1875, closed 1928)

- Otahuhu Workshops, Auckland (opened 1928, closed 1992)

Minor workshops

None of these minor workshops manufactured locomotives, although major overhauls were carried out:

- Greymouth (Elmer Lane)

- Invercargill

- Napier

- New Plymouth (Sentry Hill) from 1880

- Westport

Locomotives

Steam locomotives built and rebuilt at NZR workshops:[28]

| Workshops | New | Rebuild | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addington | 114 | 12 | 126 |

| Hillside | 165 | 21 | 186 |

| Hutt | 77 | 0 | 77 |

| Petone | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| Newmarket | 1 | 9 | 10 |

| Westport | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 361 | 49 | 410 |

Nine of the ED electric locomotives were constructed (assembled) at the Hutt (7) and Addington (2) workshops. Various diesel locomotives have been rebuilt at NZR workshops, for example five of the DA as DC, though most rebuilding has been contracted out. Hillside built 9 NZR TR class diesel shunters.

The Auckland workshops (Newmarket, then Otahuhu) specialised in car and wagon work, and in repairs and maintenance.

Private firms that built steam locomotives for NZR

British companies, e.g.:

- Avonside Engine Company (Fairlie and Fell locomotives)

- Beyer, Peacock and Company

- Clayton Carriage and Wagon

- Dübs and Company

- Henry Hughes's Locomotive & Tramway Engine Works

- Hunslet Engine Company

- Nasmyth, Wilson and Company

- Neilson and Company

- North British Locomotive Company (built a quarter (141) of NZR steam locomotives)

- Robert Stephenson and Hawthorns

- Sharp, Stewart and Company

- Vulcan Foundry

- Yorkshire Engine Co

American companies, e.g.:

- Brooks Locomotive Works Built Ub17 during purchase by ALCO

- Baldwin Locomotive Works (built 111 steam locotives for NZR and the WMR).

- Richmond Locomotive Works Built Ub371 during purchase by ALCO

- Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works

New Zealand companies:

- James Davidson & Co, Dunedin

- A & G Price, Thames

- E. W. Mills and Company

- Scott Brothers, Christchurch

Companies that supplied NZR with diesel locomotives

- Clyde Engineering

- Commonwealth Engineering

- Drewry Car Co.

- Electro-Motive Diesel

- English Electric various British contractors

- English Electric, Australia

- General Electric

- General Motors Diesel

- Goninan

- Hillside Engineering, formerly Hillside Workshops of NZR

- Hitachi

- Hunslet Engine Company

- Hutt Workshops of NZR

- Mitsubishi Heavy Industries

- A & G Price, Thames

- Toshiba

- Vulcan Foundry

Suppliers of electric traction to NZR

- English Electric (several)

- Ganz-Mavag (New Zealand EM class electric multiple unit)

- Goodman Manufacturing (New Zealand EB class locomotive)

- Toshiba (New Zealand EA class locomotive)

Suppliers of bus and coach chassis to NZR

- Associated Equipment Company

- Albion Motors

- Bedford Vehicles Supplied a record 1260 Bedford SB chassis (largest fleet of Bedford SB buses in the world). As well as around 400 trucks

- Ford

- Hino Motors

- Volvo

Suppliers of ferries to NZR

- John McGregor and Co, Dunedin, New Zealand. Builders of TSS Earnslaw.

- William Denny and Brothers, Dumbarton, Scotland. Builders of GMV Aramoana.

- Vickers Limited, Newcastle, England. Builders of GMV Aranui.

- Chantiers Dubegion, Nantes, France. Builders of MV Arahanga and MV Aratika.

- Aalborg Vaerft, Denmark. Builders of DEV Arahura.

- Astillero Barreras, Spain. Builders of DEV Aratere.

People

- Garnet Hercules Mackley, General Manager 1933—1940, later member of parliament

- A. L. Beattie, Chief Mechanical Engineer

- George Troup, Architect, Mayor of Wellington

- Whitford Brown, Civil Engineer, Mayor of Porirua

- Graham Latimer, was stationmaster Kaiwaka, later president of New Zealand Maori Council

- Major Norman Frederick Hastings DSO, Engineering Fitter Petone Railways Workshop killed on Gallipoli and commemorated on the Petone Railway Station memorial.

- Ritchie Macdonald, worked at Otahuhu Workshops, union secretary, later member of parliament

- Alf Cleverley, fitter at Petone and Hutt Workshops, Olympic boxer

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Churchman & Hurst 1991, p. 1.

- ↑ "New Zealand Railways Corporation Act 1981, s1(2)". Public Access to Legislation website. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Stott & Leitch 1988, p. 15.

- 1 2 "Birth of a National Railway System". Te Ara. 1966.

- ↑ Stott & Leitch 1988, p. 21.

- ↑ Ken R Cassells (1994). Uncommon Carrier. NZRLS.

- ↑ Pierre 1981, p. 26.

- 1 2 Stott & Leitch 1988, p. 171.

- 1 2 Stott & Leitch 1988, p. 45.

- ↑ Stott & Leitch 1988, p. 44.

- ↑ Stott & Leitch 1988, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Stott & Leitch 1988, p. 51.

- 1 2 Stott & Leitch 1988, p. 52.

- ↑ Scott, p. 54.

- ↑ Stott & Leitch 1988, p. 55.

- ↑ Pierre 1981, p. 151.

- ↑ Pierre 1981, p. 152.

- 1 2 Scott, p. 57.

- ↑ Churchman & Hurst 1991, p. 30.

- ↑ "RAILWAY POLICY. (Auckland Star, 1925-08-27)". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ↑ Pierre 1981, p. 157.

- ↑ Scott, p. 56.

- ↑ Scott, p. 62.

- ↑ Churchman & Hurst 1991, p. 31.

- ↑ "Electric trains come to Wellington". New Zealand History online. 20 December 2012.

- ↑ Snell, J.B. (June 1954). Cooke, B.W.C., ed. "The New Zealand Government Railways - 1". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 100 no. 638. Westminster: Tothill Press. p. 379.

- ↑ Rob Merrifield (Winter–Spring 1990). "Land Transport Deregulation in New Zealand, 1983-1989". New Zealand Railway Observer.

- ↑ Lloyd 2002, p. 187-189.

Bibliography

- Bromby, Robin (2003). Rails that built a nation - an encyclopedia of New Zealand Railways. Grantham House New Zealand. ISBN 1-86934-080-9.

- Churchman, Geoffrey B.; Hurst, Tony (1991). The Railways of New Zealand: A Journey Through History (reprint ed.). HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand). ISBN 978-0-908876-20-4.

- Pierre, Bill (1981). North Island Main Trunk: An Illustrated History. A.H. & A.W. Reed. ISBN 0-589-01316-5.

- Lloyd, W. G. (2002). Register of New Zealand Railways Steam Locomotives 1863-1971. ISBN 0-9582072-1-6.

- Stott, Bob; Leitch, David (1988). New Zealand Railways - The First 125 Years. ISBN 0-7900-0000-8.

External links

| Preceded by Public Works Department |

New Zealand Railways Department 1880-1981 |

Succeeded by New Zealand Railways Corporation |