Fort Madison, Iowa

| Fort Madison, Iowa | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Downtown Fort Madison (2007) | |

| Motto: "Always Moving"[1] | |

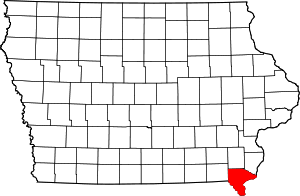

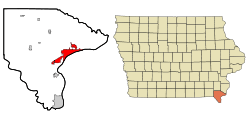

Location within Lee County and Iowa | |

| Coordinates: 40°37′43″N 91°20′20″W / 40.62861°N 91.33889°WCoordinates: 40°37′43″N 91°20′20″W / 40.62861°N 91.33889°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State |

|

| County | Lee |

| Area[2] | |

| • Total | 13.23 sq mi (34.27 km2) |

| • Land | 9.49 sq mi (24.58 km2) |

| • Water | 3.74 sq mi (9.69 km2) |

| Elevation | 528 ft (161 m) |

| Population (2010)[3] | |

| • Total | 11,051 |

| • Estimate (2012[4]) | 11,020 |

| • Density | 840/sq mi (320/km2) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 52627 |

| Area code(s) | 319 |

| FIPS code | 19-28605 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0456689 |

| Website | City of Fort Madison |

|

Old Fort Madison Site | |

|

Monument marking the location of Fort Madison. | |

| |

| Nearest city | Fort Madison, Iowa |

|---|---|

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1808 |

| NRHP Reference # | 73000734[5] |

| Added to NRHP | May 7, 1973 |

Fort Madison is a city and a county seat of Lee County, Iowa, United States[6] along with Keokuk. Of Iowa's 99 counties, Lee County is the only one with two county seats. The population was 11,051 at the 2010 census. Located along the Mississippi River in the state's southeast corner, it lies between small bluffs along one of the widest portions of the river.

Overview

Fort Madison was the location of the first U.S. military fort in the upper Mississippi region; a replica of the fort stands along the river.[7] Sheaffer Pens were developed and made in Fort Madison for many years. The city is the location of the Iowa State Penitentiary—the state's maximum security prison for men. Fort Madison is the Mississippi river crossing and station stop for Amtrak's Southwest Chief. Fort Madison has the last remaining double swing-span bridge on the Mississippi River, the Fort Madison Toll Bridge. It has a top level for cars and a bottom level for trains; it is also the world's largest . The Fort Madison Downtown Commercial Historic District is a collection of well-preserved historic storefronts from the late 19th century.

The Original Fort Madison (1808–1813)

The city of Fort Madison was established around the site of the historic Fort Madison (1808–1813), which was the first permanent U.S. military fortification on the Upper Mississippi. Fort Madison was the site of Black Hawk's first battle against U.S. troops, the only real War of 1812 battle fought west of the Mississippi. It was also the location of the first U.S. military cemetery in the upper Midwest.[8] The fort was named for James Madison, fourth President of the United States.[9]

Fort Madison was one of three posts established by the U.S. Army to establish control over the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase territories. Fort Madison was built to control trade and pacify Native Americans in the Upper Mississippi River region. The other two posts were Fort Belle Fontaine near St. Louis, which controlled the mouth of the Missouri, and Fort Osage, near what is now Kansas City, which controlled trade with western Native American tribes.[10]

Location of the fort

A disputed 1804 treaty with the Sauk and affiliated tribes led to the U.S. claim of control over western Illinois and parts of what is now Iowa. To establish control, the U.S. Army set out to construct a post near the mouth of the Des Moines River, a major trading route into the interior of Iowa. Not finding suitable land near the mouth of the Des Moines, the expedition also considered land near Quashquame's Sauk and Meskwaki village at the head of the Des Moines Rapids, a choke point of trade and transportation on the Upper Mississippi below modern Montrose. Again, this land was not considered suitable for a fort. The Army settled on a location several miles upstream at what is now the city of Fort Madison.[11]

First called Fort Belleview, this post was soon deemed inadequate. It was poorly situated at the base of a bluff next to a deep ravine, areas from which enemies could safely fire at the fort. Trade led to resentment among Indians, especially the Sauk; the 1804 treaty was considered invalid by the Sauk, the fort threatened established trading networks, and American trade goods were considered inferior to French or British goods.[12]

Black Hawk lamented over the new fort, and disparaged its construction in his autobiography:

- A number of people immediately went down to see what was going on, myself among them. On our arrival we found that they were building a fort. The soldiers were busily engaged in cutting timber, and I observed that they took their arms with them when they went to the woods. The whole party acted as they would do in an enemy's country. The chiefs held a council with the officers, or head men of the party, which I did not attend, but understood from them that the war chief had said that they were building homes for a trader who was coming there to live, and would sell us goods very cheap, and that the soldiers were to remain to keep him company. We were pleased at this information and hoped that it was all true, but we were not so credulous as to believe that all these buildings were intended merely for the accommodation of a trader. Being distrustful of their intentions, we were anxious for them to leave off building and go back down the river.

- —Black Hawk, Autobiography (1882)

- A number of people immediately went down to see what was going on, myself among them. On our arrival we found that they were building a fort. The soldiers were busily engaged in cutting timber, and I observed that they took their arms with them when they went to the woods. The whole party acted as they would do in an enemy's country. The chiefs held a council with the officers, or head men of the party, which I did not attend, but understood from them that the war chief had said that they were building homes for a trader who was coming there to live, and would sell us goods very cheap, and that the soldiers were to remain to keep him company. We were pleased at this information and hoped that it was all true, but we were not so credulous as to believe that all these buildings were intended merely for the accommodation of a trader. Being distrustful of their intentions, we were anxious for them to leave off building and go back down the river.

Attacks on Fort Madison

Almost from the beginning, the fort was attacked by Sauk and other tribes. U.S. troops were harassed when they left the fort, and in April 1809 an attempted storming of the fort was stopped only by threat of cannon fire.[13]

During its existence, several improvements were made to the fort, including reinforcing the stockade and making it higher, extending the fort to a nearby bluff to provide cover from below, and constructing of additional blockhouses outside the stockade. These improvements could not fully compensate for the poor location of the fort, however, and it was again attacked in March 1812, and was the focus of a coordinated siege in the following September. The September siege was intense, and the fort was nearly overrun. Significant damage resulted to fort-related buildings, and the attack was only stopped when cannon fire destroyed a fortified Indian position.[14] Black Hawk participated in the siege, and claimed to have personally shot the fort's flag down.[15]

Final siege and abandonment

As the War of 1812 expanded to the frontier, British-allied Sauk and other tribes began a determined effort to push out the Americans and reclaim control of the upper Mississippi. Beginning in July 1813, attacks on troops outside the fort led to another siege. Conditions were so dangerous that the bodies of soldiers killed outside the fort could not be recovered, and troops could not leave the fort to collect firewood. Outbuildings were intentionally burned by the Army to prevent them from falling into Indian hands.[16]

After weeks of paralyzing siege, the Army finally abandoned the post, burning it as they evacuated. They retreated in the dark through a trench to the river, where they escaped on boats. The date of the abandonment is unknown, as much of the military correspondence from this period of the war is missing, but it probably happened in September.[16] Black Hawk observed the ruins soon after. "We started in canoes, and descended the Mississippi, until we arrived near the place where Fort Madison had stood. It had been abandoned and burned by the whites, and nothing remained but the chimneys. We were pleased to see that the white people had retired from the country."[15]

Three active battalions of the current 3rd Infantry (1–3 Inf, 2–3 Inf and 4-3 Inf) perpetuate the lineage of the old 1st Infantry Regiment, which had a detachment at Fort Madison.

Fort ruins and archaeology

Early settlers built their homes near the ruins, and the town that grew up around them was named for the fort. A large monument was erected in the early 20th century at the fort location. Archaeological excavations in the parking lot of the Sheaffer Pen Company factory in 1965 exposed the central blockhouse of the fort, as well as the foundations of officers' quarters.[17] The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[5] A replica fort was built several blocks away; much of the labor was supplied by volunteer inmates at the nearby Iowa State Penitentiary.[7]

Preservation and threats to the fort site

The fort site is now the subject of preservation efforts. After the Sheaffer Pen factory closed in 2007, the site was sold to developers. Arguing that Fort Madison is "Iowa's most important historical site", preservationists want to convert the parking lot into a memorial park dedicated to soldiers killed at the fort. So far, no agreement has been reached for its preservation.[18][19][20]

Geography

The Fort Madison is located at 40°37′43″N 91°20′20″W / 40.62861°N 91.33889°W (40.628588, −91.339005).[21]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.23 square miles (34.27 km2), of which, 9.49 square miles (24.58 km2) is land and 3.74 square miles (9.69 km2) is water.[2]

Fort Madison is famous for the Tri-State Rodeo, Mexican Fiesta, Balloons Over the Mississippi, Art in Central Park and Annual Lighted Parade.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 1,509 | — | |

| 1860 | 2,886 | 91.3% | |

| 1870 | 4,011 | 39.0% | |

| 1880 | 4,679 | 16.7% | |

| 1890 | 7,901 | 68.9% | |

| 1900 | 9,278 | 17.4% | |

| 1910 | 8,900 | −4.1% | |

| 1920 | 12,066 | 35.6% | |

| 1930 | 13,779 | 14.2% | |

| 1940 | 14,063 | 2.1% | |

| 1950 | 14,954 | 6.3% | |

| 1960 | 15,247 | 2.0% | |

| 1970 | 13,996 | −8.2% | |

| 1980 | 13,520 | −3.4% | |

| 1990 | 11,618 | −14.1% | |

| 2000 | 10,715 | −7.8% | |

| 2010 | 11,051 | 3.1% | |

| Est. 2015 | 10,717 | [22] | −3.0% |

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 11,051 people, 4,403 households, and 2,667 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,164.5 inhabitants per square mile (449.6/km2). There were 4,956 housing units at an average density of 522.2 per square mile (201.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 89.3% White, 5.5% African American, 0.4% Native American, 0.6% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.6% from other races, and 2.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.7% of the population.

There were 4,403 households of which 28.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.7% were married couples living together, 13.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.5% had a male householder with no wife present, and 39.4% were non-families. 33.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.84.

The median age in the city was 39.9 years. 21% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.2% were from 25 to 44; 28% were from 45 to 64; and 15.7% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 52.8% male and 47.2% female.

2000 census

As of the census[23] of 2000, there were 10,715 people, 4,617 households and 2,876 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,162.9 per square mile (449.2/km²). There were 5,106 housing units at an average density of 554.2 per square mile (214.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 92.64% White, 2.67% African American, 0.28% Native American, 0.61% Asian, 0.17% Pacific Islander, 2.36% from other races, and 1.28% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.44% of the population.

There were 4,617 households out of which 28.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.7% were married couples living together, 11.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.7% were non-families. 33.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.87.

Age spread: 23.6% under the age of 18, 8.4% from 18 to 24, 26.1% from 25 to 44, 23.1% from 45 to 64, and 18.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females there were 90.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $34,318, and the median income for a family was $42,067. Males had a median income of $32,530 versus $21,170 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,124. About 9.8% of families and 12.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.1% of those under age 18 and 9.1% of those age 65 or over.

Government

Fort Madison is governed by a Mayor/City Council form of government. The city council consists of a Mayor and seven council members. Five council members are elected from individual wards and two are elected at large. The mayor is elected in a citywide vote. To view current city council members see

Education

Fort Madison has a Junior College Campus Southeastern Community College (Iowa) located at 1602 Avenue F. Fort Madison also has two elementary schools (Richardson and Lincoln), one middle school (Fort Madison Middle School) and one high school (Fort Madison High School) in the Fort Madison Community School District (public). Fort Madison also has a Catholic School System, Holy Trinity High School consists of a junior/senior high school. Holy Trinity Elementary School is located a few miles away in West Point, Iowa.

Transportation

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, serves Fort Madison, operating its Southwest Chief daily in each direction between Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California. Fort Madison has a four-lane highway running through the heart of the City, US Highway 61 and Iowa Highway 2. This artery runs east and west following the river and railroad tracks. US Highway 61 connects to US Highway 34 & 218/27, Interstate 80 in Iowa; Interstate 72 in Illinois and Interstate 70 in Missouri. A US Highway 61 by-pass around the City of Fort Madison was completed and opened in the fall of 2011.

Notable people

- Mark W. Balmert, U.S. Navy admiral

- Ryan Bowen, NBA player

- Todd Farmer, writer, actor, and film producer

- Bob Fry, professional golfer

- Kate Harrington, poet

- Thomas M. Hoenig, chief executive of the Tenth District Federal Reserve Bank, in Kansas City[24]

- James Johnson Duderstadt, President of the University of Michigan

- Patty Judge, 46th Lieutenant Governor

- Jerry Junkins, CEO of Texas Instruments, Incorporated

- Dick Klein, founder of the Chicago Bulls

- Anna Malle, pornographic actress

- Dennis O'Keefe, actor, star of films such as Raw Deal

- James Theodore Richmond, writer and conservationist

- Aloysius Schulte, first President of St. Ambrose College

- Walter A. Sheaffer, founder of the W.A. Sheaffer Pen Company

- George Henry Williams, United States Senator

Sister cities

References

- ↑ "Fort Madison, Iowa". Fort Madison, Iowa. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- 1 2 Old Fort Madison: http://www.oldfortmadison.com/

- ↑ For general histories of Fort Madison, refer to Jackson 1958, 1960, 1966; Prucha 1964, 1969; Van der Zee 1913, 1914, 1918.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 129.

- ↑ Prucha (1964, 1969)

- ↑ Jackson (1958, 1960)

- ↑ Jackson (1960); Van der Zee (1914)

- ↑ Van der Zee (1918); Jackson (1958; 1966)

- ↑ Jackson (1960); Van der Zee (1913, 1918)

- 1 2 Black Hawk (1882)

- 1 2 Van der Zee (1918); Jackson (1958, 1960, 1966)

- ↑ McKusick (1965, 1966)

- ↑ Bergin, Nick: "Effort to preserve fort site heats up." Burlington Hawk Eye, December 3, 2008.

- ↑ Delany, Robin: "Preservationists fear future development will rob Fort Madison of original fort site." Fort Madison Daily Democrat, December 3, 2008

- ↑ Save Fort Madison Website, http://fortmadison.googlepages.com/home

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Thomas M. Hoenig – Biography". Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Interactive City Directory". Sister Cities International. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

Further reading

- Black Hawk (1882) Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak or Black Hawk. Edited by J. B. Patterson. Continental Printing, St. Louis. Originally published 1833.

- Jackson, Donald (1958) "Old Fort Madison 1808–1813." Palimpsest 39(1).

- Jackson, Donald (1960) "A Critic's View of Old Fort Madison." Iowa Journal of History and Politics 58(1) 31–36.

- Jackson, Donald (1966) "Old Fort Madison 1808–1813." Palimpsest 47(1).

- Prucha, Francis P. (1964) A Guide to the Military Posts of the United States 1789–1895. State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison.

- Prucha, Francis P. (1969) The Sword of the Republic: The United States Army on the Frontier 1783–1846. Macmillan, New York.

- McKusick, Marshall B. (1965). "Discovering an Ancient Iowa Fort". Iowa Conservationist. 24 (1): 6–7.

- McKusick, Marshall B. (1966). "Exploring Old Fort Madison and Old Fort Atkinson". Iowan Magazine. 15: 12–51.

- Van; der Zee, Jacob (1913). "Old Fort Madison: Some Source Materials". Iowa Journal of History and Politics. 11: 517–545.

- Van; der Zee, Jacob (1914). "Forts in the Iowa County". Iowa Journal of History and Politics. 12: 163–204.

- Van; der Zee, Jacob (1918). "Old Fort Madison: Early Wars on the Eastern Border of the Iowa Country". Iowa and War. Iowa City: State Historical Society of Iowa. 7: 1–40.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Madison, Iowa. |

- City of Fort Madison

- Fort Madison Chamber of Commerce

- Old Fort Madison Museum

- Save Fort Madison Website

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Fort Madison". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "Fort Madison". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Fort Madison". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Fort Madison". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.