Pakke Tiger Reserve

| Pakhui Tiger Reserve | |

|---|---|

| Tiger reserve | |

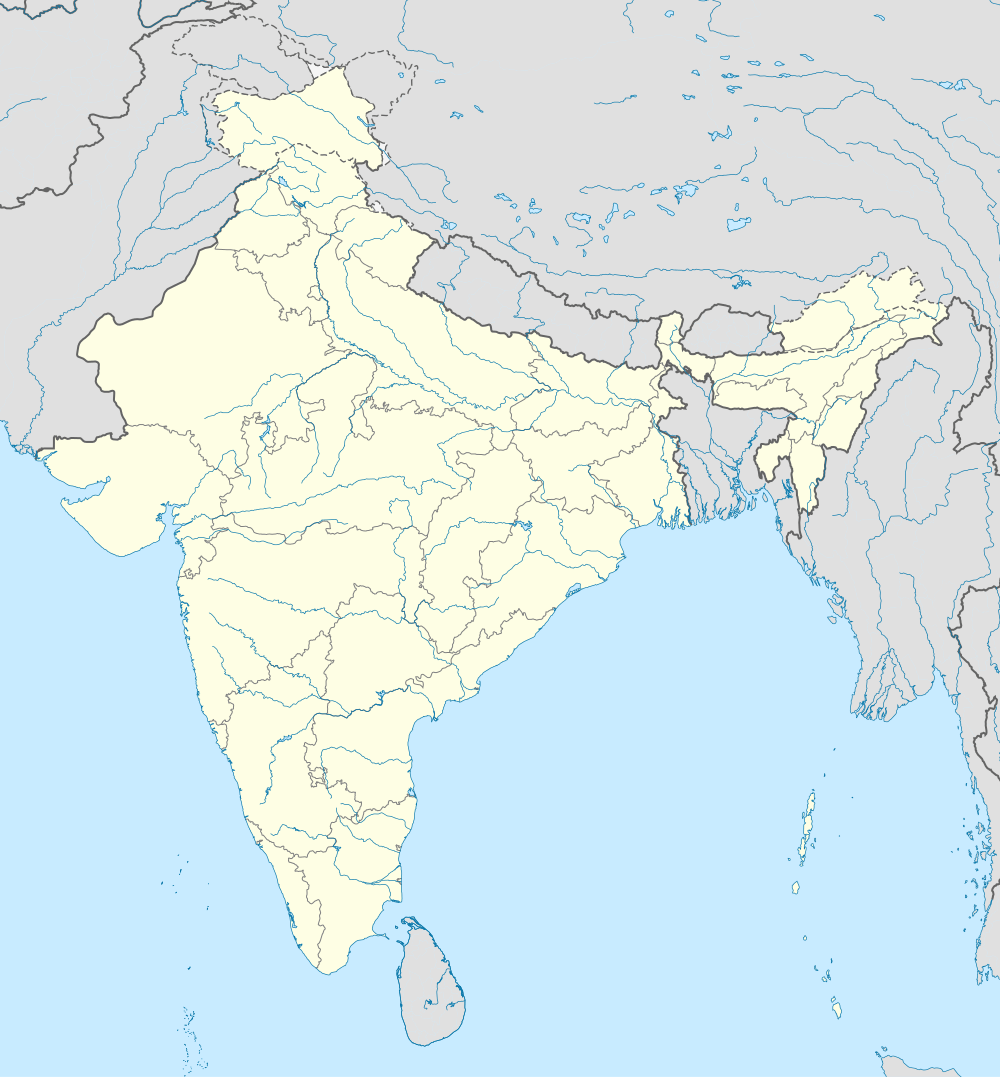

Pakhui Tiger Reserve  Pakhui Tiger Reserve Location in Arunachal Pradesh, India | |

| Coordinates: 27°05′N 92°51.5′E / 27.083°N 92.8583°ECoordinates: 27°05′N 92°51.5′E / 27.083°N 92.8583°E | |

| Country |

|

| State | Arunachal Pradesh |

| District | East Kameng/Cona County |

| Established | 1966 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 861.95 km2 (332.80 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,040 m (6,690 ft) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | English |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+5:30) |

| Vehicle registration | AR |

| Nearest city | Rangapara 36.2 kilometres (22.5 mi) NE |

| IUCN category | II |

| Governing body | Secretary (Environment & Forest), Government of Arunachal Pradesh |

| Climate | Cwa (Köppen) |

| Precipitation | 2,506 millimetres (98.7 in) |

| Avg. summer temperature | 36 °C (97 °F) |

| Avg. winter temperature | 12 °C (54 °F) |

| Website |

projecttiger |

| [1][2] | |

Pakhui Tiger Reserve is a Project Tiger tiger reserve in the East Kameng district of Arunachal Pradesh in northeastern India. The 862 square kilometres (333 sq mi) reserve is protected by the Department of Environment and Forest of Arunachal Pradesh. In a notification (CWL/D/26/94/1393-1492 Dated Itanagar the 19th April’2001) issued by the Principal Secretary the Governor of Arunachal Pradesh renamed Pakhui Wildlife Sanctuary as Pakke Wildlife Sanctuary Division.

This Tiger Reserve has won India Biodiversity Award 2016 in the category of 'Conservation of threatened species' for its Hornbill Nest Adoption Programme.

Location

Pakke Wildlife Sanctuary (862 km2, 92°36’ – 93°09'E and 26°54 – 27°16'N) lies in the foothills of the Eastern Himalaya in the East Kameng District of Arunachal Pradesh. It was declared a sanctuary in 1977, and was earlier part of the Khellong Forest Division. It has been recently declared a tiger reserve in 2002 based on a proposal in 1999.

Towards the south and south-east, the sanctuary adjoins reserved forests and Nameri National Park of Assam. To the east, lies the Pakke River and Papum Reserve Forest; to the west, the park is bounded by the Bhareli or Kameng River, Doimara RF and Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary and to the north again by the Kameng River and the Shergaon Forest Division (Tenga RF). Both Papum (1064 km2) and Doimara RF (216 km2) along with Amartala RF (west of Doimara RF) fall in Khellong Forest Division. The area of Doimara R.F. is 216 km2, while Papum R.F. encompasses an area of 1064 km2. Thus, the park is surrounded by contiguous forests on most sides. Selective logging on a commercial scale occurred in the reserve forests till 1996.

The sanctuary is delineated by rivers in the east, west and north. In addition, the area is drained by a number of small rivers and, perennial streams of the Bhareli and Pakke Rivers, both of which are tributaries of the Brahmaputra. The main perennial streams in the area are the Nameri, Khari and Upper Dikorai. The terrain of Pakhui WLS and adjoining areas is undulating and hilly. The altitude ranges from 150 m to over 2000 m above sea level.

Sessa Orchid Sanctuary and Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary are adjacent to PTR on the opposite side of the Kameng River in the west.[2]

History

The area of present Pakke Tiger Reserve was originally constituted as Pakhui Reserve Forest on July 1, 1966 and was declared as a Game Sanctuary on March 28, 1977. It was next declared as Pakhui Wildlife sanctuary in 2001, and was finally declared, as Pakhui Tiger Reserve on April 23, 2002 as the twenty sixth tiger reserve under Project Tiger of the National Tiger Conservation Authority.[3]

Geography

The reserves elevations range from 100 metres (330 ft) to 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) metres above msl. The terrain is rugged with mountainous ranges in the north and narrow plains and sloping hill valleys in the south. The sanctuary slopes southwards towards the river valley of the Brahmaputra River[2]

Climate

PTR has a subtropical climate with cold weather from November to March. The temperature varies from 12 to 36 °C (54 to 97 °F). Annual rainfall is 2,500 millimetres (98 in). It receives rainfall predominantly from the south-west monsoon in May to September and north-east monsoon from November to April. October and November are relatively dry. Winds are generally of moderate velocity. Thunderstorms occasionally occur in March–April. The average annual rainfall is 2500 mm. May and June are the hottest months. Humidity levels reach 80% during the summer.[2]

Flora

The habitat types are lowland semi-evergreen, evergreen forest and Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests. A total of 343 woody species of flowering plants (angiosperms) have been recorded from the lowland areas of the park, with a high representation of species from the Euphorbiaceae and Lauraceae families, but at least 1500 species of vascular plants are expected from Pakhui WLS, of which 500 species would be woody. While about 600 species of orchids are reported from Arunachal Pradesh, Pakhui WLS and adjoining areas also harbour many orchid species. The forest has a typical layered structure and the major emergent species are Bhelu Tetrameles nudiflora, Borpat Ailanthus grandis and Jutuli Altingia excelsa.

The general vegetation type of the entire tract is classified as Assam Valley tropical semi-evergreen forest. The forests are multi-storeyed and rich in epiphytic flora and woody lianas. The vegetation is dense, with a high diversity and density of woody lianas and climbers. The forest types include tropical semi-evergreen forests along the lower plains and foothills dominated by Kari Polyalthia simiarum, Hatipehala Pterospermum acerifolium, Karibadam Sterculia alata, Paroli Stereospermum chelonioides, Ailanthus grandis and Khokun Duabanga grandiflora.[4] The tropical semi-evergreen forests are scattered along the lower plains and foothills, dominated by Altingia excelsa, Nahar Mesua ferrea, Banderdima Dysoxylum binectariferum, Beilschmedia sp. and other middle storey trees belonging to the Lauraceae and Myrtaceae. These forests have a large number of species of economic value. Subtropical broadleaved forests of the Fagaceae and Lauraceae dominate the hill tops and higher reaches. Moist areas near streams have a profuse growth of bamboo, cane and palms. About eight species of bamboo occur in the area, in moist areas in gullies, in areas previously under settlements, or subjected to some form of disturbance on the hill slopes. At least 5 commercially important cane species grow in moist areas, along with Tokko Livistona jenkinsiana, a species used extensively by locals for thatching roofs. Along the larger perennial streams, there are shingle beds with patches of tall grassland, which give way to lowland moist forests with Outenga Dillenia indica and Boromthuri Talauma hodgsonii. Along the larger rivers, isolated trees of Semal Bombax ceiba and two species of Koroi Albizzia sp. are common.

These forests have a high percentage of tree species (64%) that are animal-dispersed, with 12% tree species being wind-dispersed.[4]

Fauna

At least 40 mammal species occur in Pakhui Tiger Reserve (PTR). Three large cats - the tiger, leopard and clouded leopard, share space with two canids – the wild dog and Asiatic jackal. Among the seven herbivore species, elephant, barking deer, gaur and sambhar are most commonly encountered. The commonest monkeys are the rhesus and Assamese macaques and the capped langur. In addition, PTR is home to as many as sixteen species of civets, weasels and mongooses. Commonly seen in pairs is the yellow-throated marten, a small but bold hunter.

Notable mammals in the tiger reserve are: tiger, leopard, clouded leopard, jungle cat, wild dog jackal, Himalayan black bear, binturong, elephant, gaur, samber, hog deer, barking deer, wilboar, yellow throated martin, Malayan giant squirrel, flying squirrel, squirrel, civet, capped langur, rhesus macaque, Assamese macaque, bison, etc. The presence of stamp tailed macaques has been reported by one researcher.[3]

At least 296 bird species have been recorded from PTR including the globally endangered white-winged wood duck, the unique ibisbill and the rare Oriental bay owl. PTR is a good place to see hornbills. Roost sites of wreathed hornbills and great hornbill can be observed on the river banks. Birds seen in PTR include: Jerdon's baza, pied falconet, white-cheeked hill-partridge, grey peacock-pheasant, elwe's crake, ibisbill, Asian emerald cuckoo, red-headed trogon, green pigeon spp., forest eagle owl, wreathed hornbill, great hornbill, collared broadbill and long-tailed broadbill, blue-naped pitta, lesser shortwing, white-browed shortwing, Daurian redstart, Leschenault's forktail, lesser necklaced laughing-thrush, silver-eared leiothrix, white-bellied yuhina, yellow-bellied flycatcher warbler, sultan tit, ruby-cheeked sunbird, maroon oriole, and crow-billed drongo.[5]

Of the over 1500 butterfly species found in India, it is estimated that PTR could be home to at least 500 species.

A total of 36 reptile species and 30 amphibian species have been reported from PTR. The Assam roof turtle, a highly endangered species, is commonly sighted. The king cobra is sometimes seen on the fringes of villages, and is not uncommon within the park. The pied warty frog, resembling bird droppings, is also found here.

Park protection

Presently, there are 27 anti-poaching camps where 104 local youth and 20 gaon burrahs (village fathers) have been employed as forest watchers. A 41 km road has been constructed to ease logistics and deter poachers. The people living around the park belong to the Nyishi community.[6] The Ghora Aabhe (a group of village chiefs) and Women Self Help Groups help authorities in wildlife protection by providing information and enforcing customary laws.[7] The Nyishi community has joined hands with civil society and the forest department to protect hornbill nests. The Nyishi tribe uses fiber glass replicas of hornbills beaks as their head gear and has fines for hunting of tigers, among other regulations.

The Ghora Aabhe Society (a group of village chiefs) was formed in 2006. A group of 12 village heads, along with the forest department, supports conservation efforts around Pakhui Tiger Reserve (PTR). Their work has been widely recognised, through several awards and articles in print media.[8] The Ghora Aabhe enforce customary laws, institute penalties against hunting and logging, aid in capacity building and spread awareness of PTR.

Research in Pakhui

PUBLICATIONS FROM RESEARCH IN PAKHUI TIGER RESERVE (in chronological order)

- Sarkar, P., Verma, S. and Menon, V. 2012. Food selection by Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). The Clarion-International Multidisciplinary Journal 1: 70-79.

- Velho, N., Ratnam, J., Srinivasan, U. and Sankaran, M. 2012. Shifts in community structure of tropical trees and avian frugivores in forests recovering from past logging. Biological Conservation 153:32-40.

- Velho, N., Isvaran, K. and Datta, A. 2012. Rodent seed predation: effects on seed survival, recruitment, abundance and dispersion of bird-dispersed tropical trees. Oecologia 167:1-10.

- Velho, N., Srinivasan, U., Prashanth, N.S. and Laurance, W. 2011. Human disease hinders anti-poaching efforts in Indian nature reserves. Biological Conservation 144: 2382-2385

- Velho, N. and Krisnadas, M. 2011. Post-logging recovery of animal-dispersed trees in a tropical forest site in north-east India. Tropical Conservation Science 4: 405-419.

- Solanki, G.S. and Kumar, A. 2010. Time budget and activities pattern of Capped langurs Trachypithecus Pileatus in Pakke wildlife sanctuary, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 107(2): 86-90

- Kumar, A., Solanki, G.S. and Sharma, B.K. 2010. Zoo therapeutic use of capped langur in traditional healthcare and the market value: view from Western Arunachal Pradesh, India. In: S.C. Tiwari (Ed.), Ethnoforestry: The future of Indian forestry. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehradun, India, 524pp.

- Lasgorceix, A. and Kothari, A. 2009. Displacement and relocation of Protected Areas: a synthesis and analysis of case studies. Economic & Political Weekly 44: 37-47.

- Velho, N., Datta, A. and Isvaran, K. 2009. Effects of rodents on seed fates of hornbill-dispersed tree species in a tropical forest in north-east India. J. Tropical Ecology 25: 507-514.

- Kumar, A. and Solanki, G.S. 2009. Cattle-carnivore conflict: A case study of Pakke Tiger Reserve in Arunachal Pradesh, India. International Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences 35: 121-127.

- Sethi, P. and Howe, H. 2009. Recruitment of hornbill-dispersed trees in hunted and logged forests of the Indian Eastern Himalaya. Conservation Biology 23: 710-718.

- Solanki, G.S., Kumar, A. and Sharma, B.K. Sharma. 2008b. Winter food selection and diet composition of capped langur Trachypithecus pileatus in Arunachal Pradesh, India. Tropical Ecology 49: 157-166.

- Datta, A., Naniwadekar, R. and Anand, M.O. 2008a. Diversity, abundance and conservation status of small carnivores in two Protected Areas in Arunachal Pradesh. Small Carnivore Conservation 39: 1-10.

- Datta, A. and Goyal, S.P. 2008b. Responses of diurnal tree squirrels to selective logging in western Arunachal Pradesh. Current Science 95: 895-902.

- Datta, A. and Rawat, G.S. 2008c. Dispersal modes and spatial patterns of tree species in a tropical forest in Arunachal Pradesh, north-east India. Tropical Conservation Science 1 (3): 163-183.

- Kumar, A. and Solanki, G.S. 2008. Population status and conservation of capped langurs (Trachypithecus pileatus) in and around Pakhuil Wildlife Sanctuary, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Primate Conservation 23: 97-105.

- Solanki, G.S., Kumar, A. and Sharma, B.K. 2008a. Feeding Ecology of Trachypithecus pileatus in India. International Journal of Primatology 29:173-182.

- Solanki, G.S., Kumar, A. and Sharma, B.K. 2007. Reproductive strategies of Trachypithecus pileatus in Arunachal Pradesh, India. International Journal of Primatology 28: 1075-1083.

- Solanki, G.S. and Kumar, A. 2006. Study on aggressive behaviour in wild population of capped langur (Trachypithecus pileatus) in India. Proceeding of Zoological Society of India 6 (1):15-30.

- Kumar, A., Solanki, G.S. and Sharma, B.K. 2005. Observation on parturition behaviour of capped langur (Trachypithecus pileatus). Primates 46 (3):215-217.

- Solanki, G.S., Chongpi, B. and Kumar, A. 2004. Ethnology of the Nishi tribes and wildlife of Arunachal Pradesh. Arunachal Forest News 20: 74-86.

- Birand, A. and Pawar, S. 2004. An ornithological survey in north-east India. Forktail 20: 15-24.

- Datta, A. and Rawat, G.S. 2004. Nest site selection and nesting success of hornbills in Arunachal Pradesh, north-east India. Bird Conservation International 14: 249-262.

- Kumar, A. and Solanki, G.S. 2004b. Ethno-sociological impact on Capped langur (Trachypithecus pileatus) and suggestions for conservation: a case study of reserve forest in Assam, India. Journal of Nature Conservation 16 (1): 107-113.

- Kumar, A. and Solanki, G.S. 2004a. A rare feeding observation on water lilies (Nymphaea Alba) by the capped langur, Trachypithecus pileatus. Folia Primatologica 75 (3):157-159.

- Datta, A. and Rawat, G.S. 2003. Foraging patterns of sympatric hornbills in the non-breeding season in Arunachal Pradesh, north-east India. Biotropica 35 (2): 208-218.

- Kumar, A. and Solanki, G.S. 2003. Food preference of Rhesus monkey Macaca mulatta during the pre-monsoon & monsoon season, Pakhui Wildlife Sanctuary Arunachal Pradesh. Zoo’s Print Journal 18 (8): 1172-1174.

- Padmawathe, R., Qureshi, Q. & Rawat, G. S. 2003. Effects of selective logging on vascular epiphyte diversity in a moist lowland forest of Eastern Himalaya, India. Biological Conservation, 119: 81-92.

- Datta, A. 2001. Pheasant abundance in selectively logged and unlogged forests of western Arunachal Pradesh, north-east India. J. Bombay nat. Hist. Soc. 97 (2): 177-183.

- Datta, A. 1998. Hornbill abundance in unlogged forest, selectively logged forest and a plantation in western Arunachal Pradesh. Oryx 32 (4): 285-294.

Visiting Pakke

- Essentials: trekking shoes, binoculars, camouflage, mosquito repellant

- Temperature: 12 – 34 °C

- Monsoon: June to September

- Best time to visit: November to April

Getting there

PTR is accessible through Seijosa in the east, Bhalukpong in the west and Pakke Kessang in the north.

- Roads: Seijosa is connected to Guwahati and Tezpur through the Soibari–Pakke Kessang road. Bhalukpong gate is well connected through the Tezpur-Bomdila tourist route. Pakke Kessang is accessible through Itanagar or Seppa route.

- Nearest railway station: Soibari (approx. 36 km), Biswanath Chariali (approx. 47 km) and Rangapara (approx. 60 km) from Seijosa or Bhalukpong. The nearest major town is Tezpur (approx. 65 km; 2 hours by road).

- Nearest airport: Tezpur (approx. 50 km) and Guwahati (approx. 280 km) from Seijosa or Bhalukpong.

- Bus services: Arunachal Pradesh State Transport (APST) or private bus services are available daily from Tezpur to Seijosa, Seppa or Itanagar. State buses do not ply on Thursdays. Bhalukpong is well connected with Tezpur, Rangapara, Guwahati, Balipara and Bomdila through APST bus services.

- Other transport options: Taxis can be hired from Biswanath Chariali/Tezpur/Rangapara/Balipara/Soibari/Itanagar to Seijosa, Bhalukpong or Pakke Kessang. Shared taxi services are available from Soibari to Seijosa, and from Itanagar/Seppa to Pakke Kessang.

Stay

Pakhui has among the last large intact tracts of tropical forests of northeast India. There are good chances to see ibisbills, tiger signs, elephants, and hornbills. The managing staff of community-owned tourism initiatives are mainly representatives from Ghora Aabhe that are supported by Help Tourism—a rural tourism organization and the Pakhui Tiger Reserve Authority (under the leadership of local DFO). Food, stay, safaris and other arrangements are completely taken care of if you stay here.

The activities available for visitors staying at the community owned tourism initiatives are:

- A walk through the forest with locally employed hornbill nest protectors.

- Jeep ride and walk: 13 km jeep ride to Khari

- Walks around the village

- Cultural programs with gaon burrahs and women from Self Help Groups

- Bird watching and education tours.

Comfortable accommodation is available at West Bank (Seijosa), Khari and Langka forest rest houses on the eastern side of the park. Food rations (easily available at local stores) need to be arranged by the people visiting and availing forest department accommodation. Hotels and tourist lodges are available in Bhalukpong. Accommodation is also available 4 km from Bhalukpong at the Tipi forest rest house. The western side of PTR can be accessed, after crossing the Kameng river.

An Inner Line Permit (for Indian nationals) or Restricted Area Permit (for foreigners) is required for entry into Arunachal Pradesh. The ILP can be obtained from the office of the Deputy Resident Commissioner.

References

- ↑ Birand, A & Pawar, S (2004) An ornithological survey in north-east India. Forktail20. p.15–24. PDF

- 1 2 3 4 Tana Tapi, Divisional Forest Officer, "General Information", Pakhui Tiger Reserve, PTR, Kalyan Varma, retrieved 2012-02-26

- 1 2 "Pakhui Tiger Reserve", Reserve Guide - Project Tiger Reserves In India, National Tiger Conservation Authority, retrieved 2012-02-26

- 1 2 Datta,, A.; Rawat, G.S. "Dispersal modes and spatial patterns of tree species in a tropical forest in Arunachal Pradesh, north-east India.". Tropical Conservation Science. 1 (3): 163–183.

- ↑ "Pakke Tiger Reserve, General information", Birding Hotspost of Western Arunachal Pradesh, Eaglenest Biodiversity Project, 2005-04-13, retrieved 2012-02-26

- ↑ "Forest guard's life is tough".

- ↑ Velho, Nandini. "Hunters are invited".

- ↑ "Earth heroes awards".

External links

- Map - Pakhui Tiger Reserve

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pakke Tiger Reserve. |