Pancreaticoduodenectomy

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

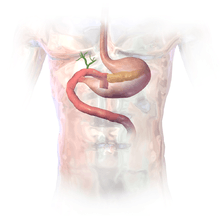

The pancreas, stomach, and bowel are joined back together after a pancreaticoduodenectomy | |

| ICD-9-CM | 52.7 |

| MeSH | D016577 |

A pancreaticoduodenectomy, pancreatoduodenectomy,[1] Whipple procedure, or Kausch-Whipple procedure, is a major surgical operation involving the removal of the head of the pancreas, the duodenum including the duodenal papilla or ampulla of Vater, the proximal jejunum, gallbladder, and often the distal stomach. This operation is performed to treat cancerous tumours of the head of the pancreas, malignant tumors involving the common bile duct, duodenal papilla or ampulla of Vater, or duodenum near the pancreas, some precancerous lesions, some cases of pancreatitis with or without a definitive cause, and rarely, severe trauma.

Anatomy involved in the procedure

The most common technique of a pancreaticoduodenectomy consists of the en bloc removal of the distal segment (antrum) of the stomach, the first and second portions of the duodenum, the head of the pancreas, the common bile duct, and the gallbladder.

The basic concept behind the pancreaticoduodenectomy is that the head of the pancreas and the duodenum share the same arterial blood supply (the gastroduodenal artery). These arteries run through the head of the pancreas, so that both organs must be removed if the single blood supply is severed. If only the head of the pancreas were removed it would compromise blood flow to the duodenum, resulting in tissue necrosis.

Medical uses

The Whipple procedure today is very similar to Whipple's original procedure. It consists of removal of the distal half of the stomach (antrectomy), the gall bladder and its cystic duct (cholecystectomy), the common bile duct (choledochectomy), the head of the pancreas, duodenum, proximal jejunum, and regional lymph nodes. Reconstruction consists of attaching the pancreas to the jejunum (pancreaticojejunostomy), attaching the hepatic duct to the jejunum (hepaticojejunostomy) to allow digestive juices and bile respectively to flow into the gastrointestinal tract, and attaching the stomach to the jejunum (gastrojejunostomy) to allow food to pass through. Whipple originally used the sequence: bile duct, pancreas and stomach, whereas presently the popular method of reconstruction is pancreas, bile duct and stomach, also known as Child's operation.

Originally performed in a two-step process, Whipple refined his technique in 1940 into a one-step operation. Using modern operating techniques, mortality from a Whipple procedure is around 5% in the United States (less than 2% in high-volume academic centers).[2]

Pancreaticoduodenectomy versus total pancreatectomy

Clinical trials have failed to demonstrate significant survival benefits of total pancreatectomy, mostly because patients who submit to this operation tend to develop a particularly severe form of diabetes mellitus called brittle diabetes. Sometimes the pancreaticojejunostomy may not hold properly after the completion of the operation and infection may spread inside the patient. This may lead to another operation shortly thereafter in which the remainder of the pancreas (and sometimes the spleen) is removed to prevent further spread of infection and possible morbidity.

Pylorus-sparing pancreaticoduodenectomy

In recent years the pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (also known as Traverso-Longmire procedure/PPPD) has been gaining popularity, especially among European surgeons. The main advantage of this technique is that the pylorus, and thus normal gastric emptying, is preserved.[3] A recent meta-analysis included 27 studies with a total of 2,599 patients. The results showed that pylorus removal of pancreaticoduodenectomy doesn’t significantly prevent delayed gastric emptying.[4] However, some doubts remain on whether it is an adequate operation from an oncological point of view. In practice, it shows similar long-term survival as a Whipple's (pancreaticoduodenectomy + hemigastrectomy), but patients benefit from improved recovery of weight after a PPPD, so this should be performed when the tumour does not involve the stomach and the lymph nodes along the gastric curvatures are not enlarged.[5]

Another controversial point is whether patients benefit from retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy.

Pylorus-sparing pancreaticoduodenectomy versus standard Whipple procedure

Compared to the standard Whipple procedure, the pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy technique is associated with shorter operation time and less intraoperative blood loss, requiring less blood transfusion. Post-operative complications, hospital mortality and survival do not differ between the two methods.[6][7][8]

Morbidity and mortality

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is considered, by any standard, to be a major surgical procedure.

Many studies have shown that hospitals where a given operation is performed more frequently have better overall results (especially in the case of more complex procedures, such as pancreaticoduodenectomy). A frequently cited study published in The New England Journal of Medicine found operative mortality rates to be four times higher (16.3 v. 3.8%) at low-volume (averaging less than one pancreaticoduodenectomy per year) hospitals than at high-volume (16 or more per year) hospitals. Even at high-volume hospitals, morbidity has been found to vary by a factor of almost four depending on the number of times the surgeon has previously performed the procedure.[9] de Wilde et al. have reported statistically significant mortality reductions concurrent with centralization of the procedure in the Netherlands.[10]

One study reported actual risk to be 2.4 times greater than the risk reported in the medical literature, with additional variation by type of institution.[11]

History

This procedure was originally described by Alessandro Codivilla, an Italian surgeon, in 1898. The first resection for a periampullary cancer was performed by the German surgeon Walther Kausch in 1909 and described by him in 1912. It is often called Whipple's procedure or the Whipple procedure, after the American surgeon Allen Whipple who devised an improved version of the surgery in 1935[12] and subsequently came up with multiple refinements to his technique.

Nomenclature

Fingerhut et al. argue that while the terms pancreatoduodenectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy are often used interchangeably in the medical literature, scrutinizing their etymology yields different definitions for the two terms.[1] As a result, the authors prefer pancreatoduodenectomy over pancreaticoduodenectomy for the name of this procedure.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Fingerhut, A; Vassiliu, P; Dervenis, C; Alexakis, N; Leandros, E (2007). "What is in a word: Pancreatoduodenectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy?". Surgery. 142 (3): 428–9. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2007.06.002. PMID 17723902.

- ↑ http://www.ddc.musc.edu/ddc_pub/patientInfo/surgeries/whipple.htm Archived February 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Public Information Site | MUSC Digestive Disease Center

- ↑ Testini, M; Regina, G; Todisco, C; Verzillo, F; Di Venere, B; Nacchiero, M (1998). "An unusual complication resulting from surgical treatment of periampullary tumours". Panminerva medica. 40 (3): 219–22. PMID 9785921.

- ↑ Wu, WM; Hong, XF (2014). "The effect of pylorus removal on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of 2,599 patients". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e108380. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108380. PMC 4182728

. PMID 25272034.

. PMID 25272034. - ↑ Michalski, Christoph W; Weitz, JüRgen; Büchler, Markus W (2007). "Surgery Insight: Surgical management of pancreatic cancer". Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 4 (9): 526–35. doi:10.1038/ncponc0925. PMID 17728711.

- ↑ Karanicolas, PJ; Davies, E; Kunz, R; Briel, M; Koka, HP; Payne, DM; Smith, SE; Hsu, HP; Lin, PW (2007). "The pylorus: Take it or leave it? Systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus standard whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary cancer". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 14 (6): 1825–34. doi:10.1245/s10434-006-9330-3. PMID 17342566.

- ↑ Diener, MK; Knaebel, HP; Heukaufer, C; Antes, G; Büchler, MW; Seiler, CM (2007). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus classical pancreaticoduodenectomy for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma". Annals of Surgery. 245 (2): 187–200. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000242711.74502.a9. PMC 1876989

. PMID 17245171.

. PMID 17245171. - ↑ Iqbal, N; Lovegrove, RE; Tilney, HS; Abraham, AT; Bhattacharya, S; Tekkis, PP; Kocher, HM (2008). "A comparison of pancreaticoduodenectomy with pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: A meta-analysis of 2822 patients". European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 34 (11): 1237–45. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2007.12.004. PMID 18242943.

- ↑ "The Whipple Procedure". Pri-Med Patient Education Center,. Harvard Health Publications. 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011.

- ↑ De Wilde, R.F.; et al. (2012). "Impact of nationwide centralization of pancreaticoduodenectomy on hospital mortality". The British Journal of Surgery. 99 (3): 404–410. doi:10.1002/bjs.8664. PMID 22237731.

- ↑ Syin, Dora; Woreta, Tinsay; Chang, David C.; Cameron, John L.; Pronovost, Peter J.; Makary, Martin A. (2007). "Publication Bias in Surgery: Implications for Informed Consent". Journal of Surgical Research. 143 (1): 88–93. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.035. PMID 17950077.

- ↑ synd/3492 at Who Named It?

External links

- Toronto Whipple Clinical Pathway Education App - Open access App for patient and caregiver education

- The Toronto Video Atlas of Liver, Pancreas and Transplant Surgery – Video of Whipple procedure

- The Toronto Video Atlas of Liver, Pancreas and Transplant Surgery Patient Education Module – Patient and Family Education video for the Whipple procedure

- " Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy: a historical comment Adrian O'Sullivan – The original description of Whipple's operation together with a modern commentary