Piezoelectric sensor

A piezoelectric sensor is a device that uses the piezoelectric effect, to measure changes in pressure, acceleration, temperature, strain, or force by converting them to an electrical charge. The prefix piezo- is Greek for 'press' or 'squeeze'.

Applications

Piezoelectric sensors are versatile tools for the measurement of various processes. They are used for quality assurance, process control, and for research and development in many industries. Pierre Curie discovered the piezoelectric effect in 1880, but only in the 1950s did manufacturers begin to use the piezoelectric effect in industrial sensing applications. Since then, this measuring principle has been increasingly used, and has become a mature technology with excellent inherent reliability.

They have been successfully used in various applications, such as in medical, aerospace, nuclear instrumentation, and as a tilt sensor in consumer electronics[1] or a pressure sensor in the touch pads of mobile phones. In the automotive industry, piezoelectric elements are used to monitor combustion when developing internal combustion engines. The sensors are either directly mounted into additional holes into the cylinder head or the spark/glow plug is equipped with a built-in miniature piezoelectric sensor.[2]

The rise of piezoelectric technology is directly related to a set of inherent advantages. The high modulus of elasticity of many piezoelectric materials is comparable to that of many metals and goes up to 106 N/m². Even though piezoelectric sensors are electromechanical systems that react to compression, the sensing elements show almost zero deflection. This gives piezoelectric sensors ruggedness, an extremely high natural frequency and an excellent linearity over a wide amplitude range. Additionally, piezoelectric technology is insensitive to electromagnetic fields and radiation, enabling measurements under harsh conditions. Some materials used (especially gallium phosphate or tourmaline) are extremely stable at high temperatures, enabling sensors to have a working range of up to 1000 °C. Tourmaline shows pyroelectricity in addition to the piezoelectric effect; this is the ability to generate an electrical signal when the temperature of the crystal changes. This effect is also common to piezoceramic materials. Gautschi in Piezoelectric Sensorics (2002) offers this comparison table of characteristics of piezo sensor materials vs other types:[3]

| Principle | Strain Sensitivity [V/µε] |

Threshold [µε] |

Span to threshold ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piezoelectric | 5.0 | 0.00001 | 100,000,000 |

| Piezoresistive | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 2,500,000 |

| Inductive | 0.001 | 0.0005 | 2,000,000 |

| Capacitive | 0.005 | 0.0001 | 750,000 |

| Resistive | 0.000005 | 0.01 | 50,000 |

One disadvantage of piezoelectric sensors is that they cannot be used for truly static measurements. A static force results in a fixed amount of charge on the piezoelectric material. In conventional readout electronics, imperfect insulating materials and reduction in internal sensor resistance causes a constant loss of electrons and yields a decreasing signal. Elevated temperatures cause an additional drop in internal resistance and sensitivity. The main effect on the piezoelectric effect is that with increasing pressure loads and temperature, the sensitivity reduces due to twin formation. While quartz sensors must be cooled during measurements at temperatures above 300 °C, special types of crystals like GaPO4 gallium phosphate show no twin formation up to the melting point of the material itself.

However, it is not true that piezoelectric sensors can only be used for very fast processes or at ambient conditions. In fact, numerous piezoelectric applications produce quasi-static measurements, and other applications work in temperatures higher than 500 °C.

Piezoelectric sensors can also be used to determine aromas in the air by simultaneously measuring resonance and capacitance. Computer controlled electronics vastly increase the range of potential applications for piezoelectric sensors.[4]

Piezoelectric sensors are also seen in nature. The collagen in bone is piezoelectric, and is thought by some to act as a biological force sensor.[5][6]

Principle of operation

The way a piezoelectric material is cut produces three main operational modes:

- Transverse

- Longitudinal

- Shear.

Transverse effect

A force applied along a neutral axis (y) generates charges along the (x) direction, perpendicular to the line of force. The amount of charge () depends on the geometrical dimensions of the respective piezoelectric element. When dimensions apply,

- ,

- where is the dimension in line with the neutral axis, is in line with the charge generating axis and is the corresponding piezoelectric coefficient.

Longitudinal effect

The amount of charge produced is strictly proportional to the applied force and independent of the piezoelectric element size and shape. Putting several elements mechanically in series and electrically in parallel is the only way to increase the charge output. The resulting charge is

- ,

- where is the piezoelectric coefficient for a charge in x-direction released by forces applied along x-direction (in pC/N). is the applied Force in x-direction [N] and corresponds to the number of stacked elements.

Shear effect

The charges produced are strictly proportional to the applied forces and independent of the element size and shape. For elements mechanically in series and electrically in parallel the charge is

- .

In contrast to the longitudinal and shear effects, the transverse effect make it possible to fine-tune sensitivity on the applied force and element dimension.

Electrical properties

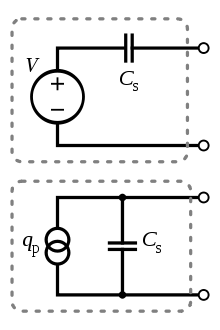

A piezoelectric transducer has very high DC output impedance and can be modeled as a proportional voltage source and filter network. The voltage V at the source is directly proportional to the applied force, pressure, or strain.[7] The output signal is then related to this mechanical force as if it had passed through the equivalent circuit.

A detailed model includes the effects of the sensor's mechanical construction and other non-idealities.[8] The inductance Lm is due to the seismic mass and inertia of the sensor itself. Ce is inversely proportional to the mechanical elasticity of the sensor. C0 represents the static capacitance of the transducer, resulting from an inertial mass of infinite size.[8] Ri is the insulation leakage resistance of the transducer element. If the sensor is connected to a load resistance, this also acts in parallel with the insulation resistance, both increasing the high-pass cutoff frequency.

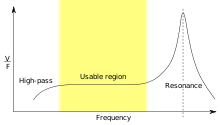

For use as a sensor, the flat region of the frequency response plot is typically used, between the high-pass cutoff and the resonant peak. The load and leakage resistance must be large enough that low frequencies of interest are not lost. A simplified equivalent circuit model can be used in this region, in which Cs represents the capacitance of the sensor surface itself, determined by the standard formula for capacitance of parallel plates.[8][9] It can also be modeled as a charge source in parallel with the source capacitance, with the charge directly proportional to the applied force, as above.[7]

Sensor design

Based on piezoelectric technology various physical quantities can be measured; the most common are pressure and acceleration. For pressure sensors, a thin membrane and a massive base is used, ensuring that an applied pressure specifically loads the elements in one direction. For accelerometers, a seismic mass is attached to the crystal elements. When the accelerometer experiences a motion, the invariant seismic mass loads the elements according to Newton's second law of motion .

The main difference in working principle between these two cases is the way they apply forces to the sensing elements. In a pressure sensor, a thin membrane transfers the force to the elements, while in accelerometers an attached seismic mass applies the forces.

Sensors often tend to be sensitive to more than one physical quantity. Pressure sensors show false signal when they are exposed to vibrations. Sophisticated pressure sensors therefore use acceleration compensation elements in addition to the pressure sensing elements. By carefully matching those elements, the acceleration signal (released from the compensation element) is subtracted from the combined signal of pressure and acceleration to derive the true pressure information.

Vibration sensors can also harvest otherwise wasted energy from mechanical vibrations. This is accomplished by using piezoelectric materials to convert mechanical strain into usable electrical energy.[10]

Sensing materials

Two main groups of materials are used for piezoelectric sensors: piezoelectric ceramics and single crystal materials. The ceramic materials (such as PZT ceramic) have a piezoelectric constant/sensitivity that is roughly two orders of magnitude higher than those of the natural single crystal materials and can be produced by inexpensive sintering processes. The piezoeffect in piezoceramics is "trained", so their high sensitivity degrades over time. This degradation is highly correlated with increased temperature.

The less-sensitive, natural, single-crystal materials (gallium phosphate, quartz, tourmaline) have a higher – when carefully handled, almost unlimited – long term stability. There are also new single-crystal materials commercially available such as Lead Magnesium Niobate-Lead Titanate (PMN-PT). These materials offer improved sensitivity over PZT but have a lower maximum operating temperature and are currently more expensive to manufacture.

See also

- Charge amplifier

- List of sensors

- Piezoelectricity

- Piezoelectric speaker

- Piezoresistive effect

- Ultrasonic homogenizer

- Ultrasonic transducer

References

- ↑ P. Moubarak, et al., A Self-Calibrating Mathematical Model for the Direct Piezoelectric Effect of a New MEMS Tilt Sensor, IEEE Sensors Journal, 12 (5) (2011) 1033 – 1042.

- ↑ , Archived December 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Gautschi, G. (2002). Piezoelectric sensorics. Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. p. 3 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Wali, R Paul (October 2012). "An electronic nose to differentiate aromatic flowers using a real-time information-rich piezoelectric resonance measurement". Procedia Chemistry: 194–202. doi:10.1016/j.proche.2012.10.146.

- ↑ Lakes, Roderic (July 8, 2013). "Electrical Properties of Bone - a review". University of Wisconsin. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ↑ Becker, Robert O.; Marino, Andrew A. "Piezoelectricity". Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- 1 2 "Interfacing Piezo Film to Electronics" (PDF). Measurement Specialties. March 2006. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- 1 2 3 Alfredo Vázquez Carazo (January 2000). "Novel Piezoelectric Transducers for High Voltage Measurements". Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya: 242.

- ↑ Karki, James (September 2000). "Signal Conditioning Piezoelectric Sensors" (PDF). Texas Instruments. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ↑ Ludlow, Chris (May 2008). "Energy Harvesting with Piezoelectric Sensors" (PDF). Mide Technology. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

External links

- Material constants of gallium phosphate

- Spark-Plug with integrated miniaturized piezoelectric pressure sensor

- Using the Piezoelectric Effect in Sensors