Glass electrode

A glass electrode is a type of ion-selective electrode made of a doped glass membrane that is sensitive to a specific ion. The most common application of ion-selective glass electrodes is for the measurement of pH. The pH electrode is an example of a glass electrode that is sensitive to hydrogen ions. Glass electrodes play an important part in the instrumentation for chemical analysis and physico-chemical studies. The voltage of the glass electrode, relative to some reference value, is sensitive to changes in the activity of certain type of ions.

History

The first studies of glass electrodes (GE) found different sensitivities of different glasses to change of the medium's acidity (pH), due to effects of the alkali metal ions.

- 1906 — M. Cremer determined that the electric potential that arises between parts of the fluid, located on opposite sides of the glass membrane is proportional to the concentration of acid (hydrogen ion concentration).[1]

- 1909 — S. P. L. Sørensen introduced the concept of pH.

- 1909 — F. Haber and Z. Klemensiewicz publicized on 28 January 1909 results of their research on the glass electrode in The Society of Chemistry in Karlsruhe (first publication — The Journal of Physical Chemistry by W. Ostwald and J. H. van 't Hoff) — 1909).[2]

- 1922 — W. S. Hughes showed that the alkali-silicate GE are similar to hydrogen electrode, reversible with respect to H+.[3]

- 1925 — P.M. Tookey Kerridge developed the first glass electrode for analysis of blood samples, and highlighted some of the practical problems with the equipment such as the high resistance of glass (50-150 megaOhms).[4] During her PhD, Kerridge developed the miniature glass electrode, maximising the surface area of the tool by heat treating the platinum with platinum chloride at red heat, thus enabling a much larger signal: her design was the predecessor of many of the glass electrodes used today.[5][6]

Applications

Glass electrodes are commonly used for pH measurements. There are also specialized ion sensitive glass electrodes used for determination of concentration of lithium, sodium, ammonium, and other ions. Glass electrodes have been utilized in a wide range of applications — from pure research, control of industrial processes, to analyze foods, cosmetics and comparison of indicators of the environment and environmental regulations: a microelectrode measurements of membrane electrical potential of a biological cell, analysis of soil acidity, etc.

Types

Almost all commercial electrodes respond to single charged ions, like H+, Na+, Ag+. The most common glass electrode is the pH-electrode. Only a few chalcogenide glass electrodes are sensitive to double-charged ions, like Pb2+, Cd2+ and some others.

There are two main glass-forming systems:

- silicate matrix based on molecular network of silicon dioxide (SiO2) with additions of other metal oxides, such as Na, K, Li, Al, B, Ca, etc.

- chalcogenide matrix based on molecular network of AsS, AsSe, AsTe.

Interfering ions

Because of the ion-exchange nature of the glass membrane, it is possible for some other ions to concurrently interact with ion-exchange centers of the glass and to distort the linear dependence of the measured electrode potential on pH or other electrode function. In some cases it is possible to change the electrode function from one ion to another. For example, some silicate pNa electrodes can be changed to pAg function by soaking in a silver salt solution.

Interference effects are commonly described by the semiempirical Nicolsky-Eisenman equation (also known as Nikolsky-Eisenman equation),[7] an extension to the Nernst equation. It is given by

where E is the emf, E0 the standard electrode potential, z the ionic valency including the sign, a the activity, i the ion of interest, j the interfering ions and kij is the selectivity coefficient. The smaller the selectivity coefficient, the less is the interference by j.

To see the interfering effect of Na+ to a pH-electrode:

Metallic function of the glass electrode

Before the 1950s, there was no explanation for some important aspects of the behavior of glass electrodes (GE) and the factual reversibility of this behavior. Some authors have refuted the existence of a particular function at GE in such solutions where they do not behave fully as hydrogen electrode, denying the phenomena of these functions, which were attributed by researchers as an incorrect interpretation of the structural changes in the surface layers of glass;[8] it was mistakenly attributing the changes of EMF element to change in the capacity of GE, and therefore received too large values of pH.[9]

George Eisenman wrote in his retrospective review:[10]

The pioneering studies of Lengiel and Blum were extended by others, who were primarily interested in the existence of Na+ sensitivity per se (i.e., the Na+ selectivity relative to H+ only) and in establishing whether or not the electrodes were reversible in the thermodynamic sense. A review of this work is given by Shultz, whose studies and those of Nicolskii and Tolmacheva are noteworthy. In fact, Shultz was the first to demonstrate, by direct comparison with a sodium amalgam electrode, that glasses behave as reversible electrodes for Na+ at neutral and alkaline pH.

In 1951 Mikhail Schultz, first proved rigorously the thermodynamical reversibility of the Na-function of different glasses in different pH ranges (later the functions for other metal ions) that confirmed the validity of one of the key hypotheses of ion-exchange theory, now the Nikolsky-Shultz-Eisenman[9][11] thermodynamic ion-exchange theory of GE.

This fact is important because ion-exchange theory was confirmed after a thermodynamically rigorous experimental confirmation of metallic function only. Before, it could be called only as a hypothesis (an epistemological). This opened the way for industrial technology GE, forming ionometry with them, later with membrane electrodes. In the context of «generalized» theory of glass electrodes, Shultz has created a framework for interpreting a mechanism of the influence of diffusion processes in glasses and resin in their electrode properties, giving new quantitative relationship, which take into account the dynamic and energetic characteristics of ion exchangers. Schulz introduced a thermodynamic consideration of processes in the membranes. Considering the different abilities of the dissociation of ionogenic groups of the glasses, his theory allows a rigorous analytical way to connect the electrode properties of glasses and ion-exchange resins with their chemical characteristics.[12]....

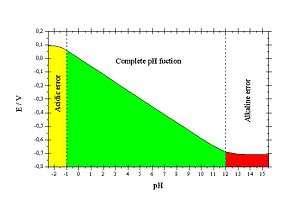

Range of a pH glass electrode

The pH range at constant concentration can be divided into 3 parts:

- Complete realization of general electrode function, where potential depends linearly on pH, realizing an ion-selective electrode for hydronium.

where F is Faraday's constant (see Nernst equation).

- Alkali error range - at low concentration of hydrogen ions (high values of pH) contributions of interfering alkali metals (like Li, Na, K) are comparable with the one of hydrogen ions. In this situation dependence of the potential on pH become non-linear.

The effect is usually noticeable at pH > 12, and concentrations of lithium or sodium ions of 0.1 moles per litre or more. Potassium ions usually cause less error than sodium ions.

- Acidic error range – at very high concentration of hydrogen ions (low values of pH) the dependence of the electrode on pH becomes non-linear and the influence of the anions in the solution also becomes noticeable. These effects usually become noticeable at pH < -1.

There are different types of pH glass electrode, some of them have improved characteristics for working in alkaline or acidic media. But almost all electrodes have sufficient properties for working in the most popular pH range from pH = 2 to pH = 12. Special electrodes should be used only for working in aggressive conditions.

Most of text written above is also correct for any ion-exchange electrodes.

Construction

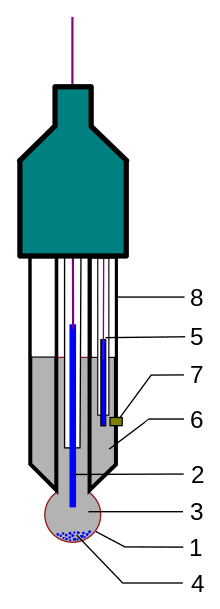

A typical modern pH probe is a combination electrode, which combines both the glass and reference electrodes into one body. The combination electrode consists of the following parts (see the drawing):

- a sensing part of electrode, a bulb made from a specific glass

- internal electrode, usually silver chloride electrode or calomel electrode

- internal solution, usually a pH=7 buffered solution of 0.1 mol/L KCl for pH electrodes or 0.1 mol/L MeCl for pMe electrodes

- when using the silver chloride electrode, a small amount of AgCl can precipitate inside the glass electrode

- reference electrode, usually the same type as 2

- reference internal solution, usually 0.1 mol/L KCl

- junction with studied solution, usually made from ceramics or capillary with asbestos or quartz fiber.

- body of electrode, made from non-conductive glass or plastics.

The bottom of a pH electrode balloons out into a round thin glass bulb. The pH electrode is best thought of as a tube within a tube. The inner tube contains an unchanging 1×10−7 mol/L HCl solution. Also inside the inner tube is the cathode terminus of the reference probe. The anodic terminus wraps itself around the outside of the inner tube and ends with the same sort of reference probe as was on the inside of the inner tube. It is filled with a reference solution of KCl and has contact with the solution on the outside of the pH probe by way of a porous plug that serves as a salt bridge.

Galvanic cell schematic representation

This section describes the functioning of two distinct types of electrodes as one unit which combines both the glass electrode and the reference electrode into one body. It deserves some explanation.

This device is essentially a galvanic cell that can be schematically represented as:

- Glass electrode || Reference Solution || Test Solution || Glass electrode

- Ag(s) | AgCl(s) | KCl(aq) || 1×10−7M H+ solution || glass membrane || Test Solution || junction || KCl(aq) | AgCl(s) | Ag(s)

In this schematic representation of the galvanic cell, one will note the symmetry between the left and the right members as seen from the center of the row occupied by the "Test Solution" (the solution whose pH must be measured). In other words, the glass membrane and the ceramic junction occupies both the same relative place in each respective electrode (indicative (sensing) electrode or reference electrode). The double "pipe symbol" (||) indicates a diffusive barrier that prevents (glass membrane), or slowing down (ceramic junction), the mixing of the different solutions. By using the same electrodes on the left and right, any potentials generated at the interfaces cancel each other (in principle), resulting in the system voltage being dependent only on the interaction of the glass membrane and the test solution.

The measuring part of the electrode, the glass bulb on the bottom, is coated both inside and out with a ~10 nm layer of a hydrated gel. These two layers are separated by a layer of dry glass. The silica glass structure (that is, the conformation of its atomic structure) is shaped in such a way that it allows Na+ ions some mobility. The metal cations (Na+) in the hydrated gel diffuse out of the glass and into solution while H+ from solution can diffuse into the hydrated gel. It is the hydrated gel, which makes the pH electrode an ion-selective electrode.

H+ does not cross through the glass membrane of the pH electrode, it is the Na+ which crosses and allows for a change in free energy. When an ion diffuses from a region of activity to another region of activity, there is a free energy change and this is what the pH meter actually measures. The hydrated gel membrane is connected by Na+ transport and thus the concentration of H+ on the outside of the membrane is 'relayed' to the inside of the membrane by Na+.

All glass pH electrodes have extremely high electric resistance from 50 to 500 MΩ. Therefore, the glass electrode can be used only with a high input-impedance measuring device like a pH meter, or, more generically, a high input-impedance voltmeter which is called an electrometer.

Storage

Between measurements any glass and membrane electrodes should be kept in a solution of its own ion It is necessary to prevent the glass membrane from drying out because the performance is dependent on the existence of a hydrated layer, which forms slowly.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glass electrode. |

References

Bates, Roger G. (1954). "Chapter 10, Glass Electrodes". Determination of pH. Wiley.

Bates, Roger G. (1973). Determination of pH: theory and practice. Wiley.

- ↑ Cremer, M. Über die Ursache der elektromotorischen Eigenschaften der Gewebe, zugleich ein Beitrag zur Lehre von Polyphasischen Elektrolytketten. — Z. Biol. 47: 56 (1906).

- ↑ F. Haber und Z. Klemensiewicz. Über elektrische Phasengrenzkräft. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. Leipzig. 1909 (Vorgetragen in der Sitzung der Karlsruher chemischen Gesellschaft am 28. Jan. 1909).

- ↑ W. S. Hughes, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 44, 2860. 1922; J. Chem. Soc. Lond., 491, 2860. 1928

- ↑ Yartsev, Alex. "History of the Glass Electrode". Deranged Physiology. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ↑ Blake-Coleman, Barrie. "Phyllis Kerridge And The Miniature Ph Electrode". Inventricity. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ↑ Kerridge, Phyllis Margaret Tookey (1925). "The Use of the Glass Electrode in Biochemistry" (PDF). Biochemical Journal. 19 (4): 611–617. doi:10.1042/bj0190611. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ D. G. Hall, Ion-Selective Membrane Electrodes: A General Limiting Treatment of Interference Effects, J. Phys. Chem 100, 7230 - 7236 (1996) article

- ↑ D. Hubbard et al., J. Nat. Bur. Stand., 22, 339(1939); 27, 27, 143(1941); 36, 511 (1946); 37, 223 (1946); 39, 561 (1947); 40, 105 (1948); 41, 163, 237 (1948)

- 1 2 Шульц М. М. Исследование натриевой функции стеклянных электродов. Учёные записки ЛГУ № 169. Серия химических наук № 13. 1953. стр. 80-156 (Shultz, M.M. Investigations into the internal function of glass electrods. Acad. LSU. Leningrad No. 169. Chemical Series of Science No. 13. 1953. pp. 80-156).

- ↑ Advances in Analytical Chemistry and Instrumentation. V. 4. Edited by Charles N. Reilley. Interscience Publishers a division of John Wiley & Sons Inc. New York — London — Sydney. 1965. pp. 220

- ↑ A. A. Belyustin. Silver ion Response as a Test for the Multilayer Model of Glass Electrodes. —Electroanalysis. Volume 11, Issue 10-11, pp. 799—803. 1999.

- ↑ М. М. Шульц. Электродные свойства стёкол. Автореферат диссертации на соискание учёной степени доктора химических наук. Изд. ЛГУ. Ленинград. 1964 (Shultz, M.M. Electrode properties of glasses. Abstract of a dissertation for the degree of Doctor in Science. Acad. LSU. Leningrad. 1964)

External links

- pH electrode practical/theoretical information

- Titration with the glass electrode and pH calculation - freeware