Polyuria

| Polyuria | |

|---|---|

| |

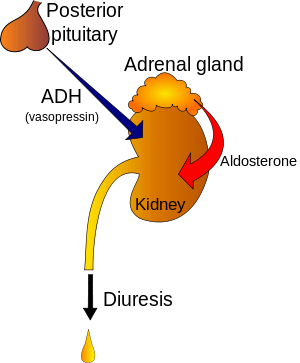

| Regulation of urine production by ADH and aldosterone | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology, nephrology |

| ICD-10 | R35 |

| ICD-9-CM | 788.42 |

| MedlinePlus | 003146 |

| Patient UK | Polyuria |

| MeSH | D011141 |

Polyuria (/ˌpɒliˈjʊəriə/) is a condition usually defined as excessive or abnormally large production or passage of urine (greater than 2.5[1] or 3[2] L over 24 hours in adults). Frequent urination is sometimes included by definition but is nonetheless usually an accompanying symptom. Increased production and passage of urine may also be termed diuresis.[3][4] Polyuria often appears in conjunction with polydipsia (increased thirst), though it is possible to have one without the other, and the latter may be a cause or an effect. Psychogenic polydipsia may lead to polyuria. [5] Polyuria is usually viewed as a symptom or sign of another disorder (not a disease by itself), but it can be classed as a disorder, at least when its underlying causes are not clear.

Causes

The most common cause of polyuria in both adults and children is uncontrolled diabetes mellitus,[2] which causes osmotic diuresis, when glucose levels are so high that glucose is excreted in the urine. Water follows the glucose concentration passively, leading to abnormally high urine output. In the absence of diabetes mellitus, the most common causes are decreased secretion of aldosterone due to adrenal cortical tumor, primary polydipsia (excessive fluid drinking), central diabetes insipidus and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.[2] Polyuria may also be due to various chemical substances, such as diuretics, caffeine, and ethanol. It may also occur after supraventricular tachycardias, during an onset of atrial fibrillation, childbirth, and the removal of an obstruction within the urinary tract. Diuresis is controlled by antidiuretics such as vasopressin, angiotensin II and aldosterone. Cold diuresis is the occurrence of increased urine production on exposure to cold, which also partially explains immersion diuresis. High-altitude diuresis occurs at altitudes above 10,000 feet (3,000 m) and is a desirable indicator of adaptation to high altitudes. Mountaineers who are adapting well to high altitudes experience this type of diuresis. Persons who produce less urine even in the presence of adequate fluid intake are probably not adapting well to altitude.

List of causes

Urinary system

- interstitial cystitis[9]

- urinary tract infection [10]

- renal tubular acidosis[11]

- Fanconi syndrome[12]

- nephronophthisis (genetic)[13]

Hormonal

- hypokalemia[14]

- diabetes mellitus[15]

- use of a corticosteroid [16]

- pheochromocytoma[17]

- hyperparathyroidism[18]

- Diabetes insipidus[19]

- hypercalcaemia[20]

- hyperthyroidism[21]

- hypopituitarism[22]

- Conn's disease [23]

- hyperglycaemia [24]

Circulation

- congestive heart failure [25]

- Cardiorespiratory disease[26]

- postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)[27]

Neurologic

- cerebral salt-wasting syndrome[28]

- neurologic damage[29]

- migraine[30]

Other

- high doses of riboflavin (vitamin B2)[31]

- high doses of vitamin D[32]

- altitude diuresis[33]

- side effect of lithium [34]

- Hemochromatosis [35]

Mechanism

Polyuria in osmotic cases, increases flow amount in the distal nephron where flow rates and velocity are low. The significant pressure increase occurring in the distal nephron takes place particularly in the cortical-collecting ducts. One study from 2008 lays out a hypothesis that hyperglycaemic and osmotic polyuria play roles ultimately in diabetic nephropathy.[36]

Diagnosis

Among the possible tests to diagnose polyuria are:[37]

- Urine test

- FBC

- Blood test

- Pituitary function test

Treatment

Depending on the cause of the polyuria, the adequate treatment should be afforded. According to NICE, desmopressin can be considered for nocturnal polyuria, which can be caused by diabetes mellitus,[38] if other medical treatments have failed. The recommendation had no studies that met the criteria for consideration.[39]

See also

References

- ↑ "Urination - excessive amount". Medline Plus. United States National Library of Medicine. 27 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Polyuria". Merck Manuals. November 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ "Definition of Diuresis". MedTerms. 30 October 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ "Diuresis". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ Parthasarathy, A. (2014-04-30). Case Scenarios in Pediatric and Adolescent Practice. JP Medical Ltd. ISBN 9789351520931.

- ↑ Rippe, editors, Richard S. Irwin, James M. (2008). Irwin and Rippe's intensive care medicine (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 909. ISBN 978-0-7817-9153-3. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Rudolf, Mary (2006). Paediatrics and Child Health (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 142. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Ronco, Claudio (2009). Critical Care Nephrology (2nd ed.). Saunders. p. 475. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Paulman, Paul (2012). Signs and Symptoms in Family Medicine: A Literature-Based Approach. Elsevier. p. 432. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Drake, edited by Michael Glynn, William M. (2012). Hutchison's clinical methods : an integrated approach to clinical practice. (23rd ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-7020-4091-7. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Lee, [edited by] Mary (2013). Basic skills in interpreting laboratory data (5th ed.). Bethesda, Md.: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-58528-343-9. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Weissman, [edited by] Barbara N. (2009). Imaging of arthritis and metabolic bone disease. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 679. ISBN 978-0-323-04177-5. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Radiology illustrated : pediatric radiology (1., 2013 ed.). [S.l.]: Springer. 2013. p. 761. ISBN 978-3-642-35572-1. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Chihan, Nina (2007). Nursing Interpreting Signs and Symptoms. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 481. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Brickell, [edited by] Wendy Arneson, Jean (2007). Clinical chemistry : a laboratory perspective. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Co. p. 411. ISBN 978-0-8036-1498-7. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Soni, Andrew Bersten, Neil (2013). Oh's Intensive Care Manual. (7. ed.). London: Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 643. ISBN 978-0-7020-4762-6. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ "Pediatric Pheochromocytoma Clinical Presentation". Medscape.com. eMedicine. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Ghosh, Srinanda (2007). MCQ's in medical surgical nursing : (with explanatory answers) (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Jaypee Bros. Medical Publishers (P) Ltd. p. 150. ISBN 81-8448-104-7. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Loscalzo, edited by Ajay K. Singh, Joseph (2014). The Brigham intensive review of internal medicine (Second ed.). p. 551. ISBN 978-0-19-935828-1. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Acute medicine 201415. [S.l.]: Scion. 2014. p. 312. ISBN 978-1-907904-25-7. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Mariani, Laura (2007). "The Renal Manifestations of Thyroid Disease". Journal of the American society of Nephrology: 22–26. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ "Panhypopituitarism Clinical Presentation". Medscape.com. eMedicine. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Kost, Michael (2004). Moderate sedation/analgesia : core competencies for practice (2nd ed.). St. Louis, Missouri.: Saunders. p. 43. ISBN 0-7216-0324-6. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Schwartz, editor, M. William Schwartz ; associate editors, Louis M. Bell, Jr. ... [et al.] ; assistant editor, Charles I. (2012). The 5-minute pediatric consult (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-4511-1656-4. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Abrams, Paul (2006). Urodynamics (3. ed.). London: Springer. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-85233-924-1. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Leslie, Shern L. Chew, David (2006). Clinical endocrinology and diabetes. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 21. ISBN 0443073031.

- ↑ Pavord, Sherif Gonem ; foreword by Ian (2010). Diagnosis in acute medicine. Oxford: Radcliffe Pub. p. 44. ISBN 978-184619-433-7. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Shanley, edited by Derek S. Wheeler, Hector R. Wong, Thomas P. (2014). A Systems Approach. (2nd ed.). Springer Verlag. p. 635. ISBN 978-1-4471-6355-8. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Parker, Rolland S. (2012). Concussive brain trauma neurobehavioral impairment and maladaptation (Second ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-4200-0798-5. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ "Migraine Headache Clinical Presentation". Medscape.com. eMedicine. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ McKee, Mitchell Bebel Stargrove, Jonathan Treasure, Dwight L. (2008). Herb, nutrient, and drug interactions : clinical implications and therapeutic strategies. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-323-02964-3. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Watkins, edited by W. Allan Walker, John B. (1997). Nutrition in pediatrics : basic science and clinical application (2nd ed.). Hamilton, Ont.: B.C. Decker. p. 205. ISBN 1-55009-026-7. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Swienton, editors, Richard B. Schwartz, John G. McManus Jr., Raymond E. (2008). Tactical emergency medicine. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7817-7332-4. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Vyas, JN (2008). Textbook of Postgraduate Psychiatry (2 Vols.). Jaypee Brothers Publishing. p. 761. ISBN 81-7179-648-6. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ "Hemochromatosis Clinical Presentation". Medscape.com. eMedicine. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Wang, Shinong; Mitu, Grace M.; Hirschberg, Raimund (2008-07-01). "Osmotic polyuria: an overlooked mechanism in diabetic nephropathy". Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 23 (7): 2167–2172. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn115. ISSN 0931-0509. PMID 18456680.

- ↑ "Polyuria. Medical Professional reference for Polyuria. | Patient". Patient. Retrieved 2015-11-08.

- ↑ Merseburger, Axel S.; Kuczyk, Markus A.; Moul, Judd W. (2014-10-21). Urology at a Glance. Springer. ISBN 9783642548598.

- ↑ "Nocturia and nocturnal polyuria in men with lower urinary tract symptoms: oral desmopressin | key-points-from-the-evidence | Advice | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

Further reading

- Movig, K. L. L.; Baumgarten, R.; Leufkens, H. G. M.; Laarhoven, J. H. M. Van; Egberts, A. C. G. (2003-04-01). "Risk factors for the development of lithium-induced polyuria". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 182 (4): 319–323. doi:10.1192/bjp.182.4.319. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 12668407.

- Kreder, Karl; Dmochowski, Roger (2007-07-10). The Overactive Bladder: Evaluation and Management. CRC Press. ISBN 9780203931622.