Boudica

| Boudica | |

|---|---|

Queen Boudica in John Opie's painting Boadicea Haranguing the Britons | |

| Born | Britannia |

| Died |

c. 60 or 61 AD Britannia |

| Other names | Boudicca, Boadicea, Buddug |

| Occupation | Queen of the Iceni |

| Spouse(s) | Prasutagus |

Boudica (/ˈbuːdᵻkə/; alternative spellings: Boudicca, Boudicea, also known as Boadicea /boʊdᵻˈsiːə/ and in Welsh as Buddug [ˈbɨ̞ðɨ̞ɡ])[1] (d. AD 60 or 61) was a queen of the British Celtic Iceni tribe who led an uprising against the occupying forces of the Roman Empire.

Boudica's husband Prasutagus ruled as a nominally independent ally of Rome and left his kingdom jointly to his daughters and the Roman emperor in his will. However, when he died his will was ignored, and the kingdom was annexed. Boudica was flogged, her daughters raped,[2] previous imperial donations to influential Britons were confiscated and the Roman financier and philosopher Seneca called in the loans he had forced on the reluctant Britons.[3]

In AD 60 or 61, when the Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus was campaigning on the island of Anglesey off the northwest coast of Wales, Boudica led the Iceni, the Trinovantes, and others in revolt.[4] They destroyed Camulodunum (modern Colchester), earlier the capital of the Trinovantes but at that time a colonia, a settlement for discharged Roman soldiers and site of a temple to the former Emperor Claudius. Upon hearing of the revolt, Suetonius hurried to Londinium (modern London), the 20-year-old commercial settlement that was the rebels' next target. The Romans, having concluded that they lacked sufficient numbers to defend the settlement, evacuated and abandoned Londinium. Boudica led 100,000 Iceni, Trinovantes, and others to fight Legio IX Hispana, and burned and destroyed Londinium and Verulamium (modern-day St Albans).[5][6]

An estimated 70,000–80,000 Romans and British were killed in the three cities by those led by Boudica.[7] Suetonius, meanwhile, regrouped his forces in the West Midlands, and, despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated the Britons in the Battle of Watling Street. The crisis caused Nero to consider withdrawing all Roman forces from Britain, but Suetonius' eventual victory over Boudica confirmed Roman control of the province. Boudica then either killed herself to avoid capture, or died of illness. The extant sources, Tacitus[8] and Cassius Dio, differ.[9]

Interest in these events revived in the English Renaissance and led to Boudica's fame in the Victorian era.[10] Boudica has remained an important cultural symbol in the United Kingdom. In 2002, she was number 35 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. The absence of native British literature during the early part of the first millennium means that knowledge of Boudica's rebellion comes solely from the writings of the Romans.

Name

Boudica has been known by several versions of her name. Raphael Holinshed calls her Voadicia, while Edmund Spenser calls her Bunduca, a version of the name that was used in the popular Jacobean play Bonduca, in 1612.[11] William Cowper's poem, Boadicea, an ode (1782) popularised an alternative version of the name.[12] From the 19th century and much of the late 20th century, Boadicea was the most common version of the name, which is probably derived from a mistranscription when a manuscript of Tacitus was copied in the Middle Ages.

Her name was clearly spelled Boudicca in the best manuscripts of Tacitus, but also Βουδουικα, Βουνδουικα, and Βοδουικα in the (later and probably secondary) epitome of Cassius Dio. The name is attested in inscriptions as Boudica in Lusitania, Boudiga in Bordeaux, and Bodicca in Algeria.[13][14]

Kenneth Jackson concludes, based on later development of Welsh and Irish, that the name derives from the Proto-Celtic feminine adjective *boudīkā, "victorious", that in turn is derived from the Celtic word *boudā, "victory" (cf. Irish bua (Classical Irish buadh), Buaidheach, Welsh buddugoliaeth), and that the correct spelling of the name in Common Brittonic (the British Celtic language) is Boudica, pronounced [bɒʊˈdiːkaː].

The closest English equivalent to the vowel in the first syllable is the ow in "bow-and-arrow".[15] The modern English pronunciation is /ˈbuːdɪkə/,[16] and it has been suggested that the most comparable English name, in meaning only, would be "Victoria".[17]

History

Background

Tacitus and Cassius Dio agree that Boudica was of royal descent. Dio describes her as "possessed of greater intelligence than often belongs to women." He also describes her as tall, with tawny hair hanging down to below her waist, a harsh voice and a piercing glare. He notes that she habitually wore a large golden necklace (perhaps a torc), a colourful tunic, and a thick cloak fastened by a brooch.[18][19]

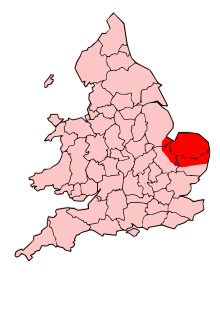

Boudicca’s husband, Prasutagus, was the king of the Iceni, a people who inhabited roughly what is now Norfolk. The Iceni initially voluntarily allied with Rome following Claudius's conquest of Southern Britain AD 43. They were proud of their independence, and had revolted in AD 47 when the then Roman governor Publius Ostorius Scapula planned to disarm all the peoples in the area of Britain under Roman control following a number of local uprisings. Ostorius defeated them and went on to put down other uprisings around Britain.[20] The Iceni remained independent. Tacitus first mentioned Prasutagus when he wrote about Boudica’s rebellion. We do not know whether he became the king after the mentioned defeat of the Iceni. The client relationship with Rome ended after the end of the rebellion.[21]

Tacitus wrote "The Icenian king Prasutagus, celebrated for his long prosperity, had named the emperor his heir, together with his two daughters; an act of deference which he thought would place his kingdom and household beyond the risk of injury. The result was contrary — so much so that his kingdom was pillaged by centurions, his household by slaves; as though they had been prizes of war." He added that Boudica was lashed and her two daughters were raped and that the estates of the leading Iceni men were confiscated.[22]

Cassius Dio wrote: "An excuse for the war was found in the confiscation of the sums of money that Claudius had given to the foremost Britons; for these sums, as Decianus Catus, the procurator of the island maintained, were to be paid back." He also said that another reasons was "the fact that Seneca, in the hope of receiving a good rate of interest, had lent to the islanders 40,000,000 sesterces that they did not want, and had afterwards called in this loan all at once and had resorted to severe measures in exacting it."[23]

Tacitus did not say why Prasutagus’ naming the emperor as his heir as well as his daughters was meant to avert the risk of injury. He did not explain why the Romans pillaged the kingdom, why they took the lands of the chiefs or why Boudica was flogged and her daughters were raped. Cassius Dio did not mention any of this. He said that the cause of the rebellion was the decision of the procurator of Britain (the chief financial officer) and Seneca (an advisor of the emperor Nero) to call in Prasutagus’ debts and the harsh measures which were taken to collect them. Tacitus does not mention these events. However, he wrote: "Alarmed by this disaster and by the fury of the province which he had goaded into war by his rapacity, the procurator Catus crossed over into Gaul."[24]

It has to be noted that this was happening while the governor of Britain, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, was away fighting in North Wales. We do not know whether he approved of these actions. We do not know who the centurions who pillaged the kingdom were and who sent them. The text of Cassius Dio seems to suggest that Seneca, who was a private citizen, was responsible for the violence. It is unlikely that a legion was sent to land of the Iceni as two of them were fighting at the island of Anglesey and the other two were stationed at their garrisons. Tacitus said that "It was against the veterans that their hatred was most intense. For these new settlers in the colony of Camulodunum drove people out of their houses, ejected them from their farms, called them captives and slaves …"[22]

Boudica's uprising

In AD 60 or 61, while the current governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, was leading a campaign against the island of Mona (modern Anglesey) in the north of Wales, which was a refuge for British rebels and a stronghold of the druids, the Iceni conspired with their neighbours the Trinovantes, amongst others, to revolt. Boudica was chosen as their leader. According to Tacitus, they drew inspiration from the example of Arminius, the prince of the Cherusci who had driven the Romans out of Germany in AD 9, and their own ancestors who had driven Julius Caesar from Britain.[25] Dio says that at the outset Boudica employed a form of divination, releasing a hare from the folds of her dress and interpreting the direction in which it ran, and invoked Andraste, a British goddess of victory.

The rebels' first target was Camulodunum (Colchester), the former Trinovantian capital and, at that time, a Roman colonia. The Roman veterans who had been settled there mistreated the locals and a temple to the former emperor Claudius had been erected there at local expense, making the city a focus for resentment. The Roman inhabitants sought reinforcements from the procurator, Catus Decianus, but he sent only two hundred auxiliary troops. Boudica's army fell on the poorly defended city and destroyed it, besieging the last defenders in the temple for two days before it fell. Archaeologists have shown that the city was methodically demolished.[26] The future governor Quintus Petillius Cerialis, then commanding the Legio IX Hispana, attempted to relieve the city, but suffered an overwhelming defeat. His infantry was wiped out—only the commander and some of his cavalry escaped.

The location of this famous destruction of the Legio IX is now claimed by some to be the village of Great Wratting, in Suffolk, which lies in the Stour Valley on the Icknield Way West of Colchester, and by a village in Essex.[27] After this defeat, Catus Decianus fled to Gaul.

When news of the rebellion reached him, Suetonius hurried along Watling Street through hostile territory to Londinium. Londinium was a relatively new settlement, founded after the conquest of AD 43, but it had grown to be a thriving commercial centre with a population of travellers, traders, and, probably, Roman officials. Suetonius considered giving battle there, but considering his lack of numbers and chastened by Petillius's defeat, decided to sacrifice the city to save the province.

Alarmed by this disaster and by the fury of the province which he had goaded into war by his rapacity, the procurator Catus crossed over into Gaul. Suetonius, however, with wonderful resolution, marched amidst a hostile population to Londinium, which, though undistinguished by the name of a colony, was much frequented by a number of merchants and trading vessels. Uncertain whether he should choose it as a seat of war, as he looked round on his scanty force of soldiers, and remembered with what a serious warning the rashness of Petilius had been punished, he resolved to save the province at the cost of a single town. Nor did the tears and weeping of the people, as they implored his aid, deter him from giving the signal of departure and receiving into his army all who would go with him. Those who were chained to the spot by the weakness of their sex, or the infirmity of age, or the attractions of the place, were cut off by the enemy.— Tacitus[7]

Londinium was abandoned to the rebels who burnt it down, slaughtering anyone who had not evacuated with Suetonius. Archaeology shows a thick red layer of burnt debris covering coins and pottery dating before AD 60 within the bounds of Roman Londinium;[28] while Roman-era skulls found in the Walbrook in 2013 were potentially linked to victims of the rebels.[29] Verulamium (St Albans) was next to be destroyed.

In the three settlements destroyed, between seventy and eighty thousand people are said to have been killed. Tacitus says that the Britons had no interest in taking or selling prisoners, only in slaughter by gibbet, fire, or cross. Dio's account gives more detail; that the noblest women were impaled on spikes and had their breasts cut off and sewn to their mouths, "to the accompaniment of sacrifices, banquets, and wanton behaviour" in sacred places, particularly the groves of Andraste.

Romans rally

While Boudica's army continued their assault in Verulamium (St. Albans), Suetonius regrouped his forces. According to Tacitus, he amassed a force including his own Legio XIV Gemina, some vexillationes (detachments) of the XX Valeria Victrix, and any available auxiliaries.[30] The prefect of Legio II Augusta, Poenius Postumus, stationed near Exeter, ignored the call,[31] and a fourth legion, IX Hispana, had been routed trying to relieve Camulodunum,[32] but nonetheless the governor was able to call on almost ten thousand men.

Suetonius took a stand at an unidentified location, probably in the West Midlands somewhere along the Roman road now known as Watling Street, in a defile with a wood behind him — but his men were heavily outnumbered. Dio says that, even if they were lined up one deep, they would not have extended the length of Boudica's line. By now the rebel forces were said to have numbered 230,000. However, this number should be treated with scepticism — Dio's account is known only from a late epitome, and ancient sources commonly exaggerate enemy numbers.

Boudica exhorted her troops from her chariot, her daughters beside her. Tacitus gives her a short speech in which she presents herself not as an aristocrat avenging her lost wealth, but as an ordinary person, avenging her lost freedom, her battered body, and the abused chastity of her daughters. She said their cause was just, and the deities were on their side; the one legion that had dared to face them had been destroyed. She, a woman, was resolved to win or die; if the men wanted to live in slavery, that was their choice.

However, the lack of manoeuvrability of the British forces, combined with lack of open-field tactics to command these numbers, put them at a disadvantage to the Romans, who were skilled at open combat due to their superior equipment and discipline. Also, the narrowness of the field meant that Boudica could put forth only as many troops as the Romans could at a given time.

First, the Romans stood their ground and used volleys of pila (heavy javelins) to kill thousands of Britons who were rushing toward the Roman lines. The Roman soldiers, who had now used up their pila, were then able to engage Boudica's second wave in the open. As the Romans advanced in a wedge formation, the Britons attempted to flee, but were impeded by the presence of their own families, whom they had stationed in a ring of wagons at the edge of the battlefield, and were slaughtered. This is not the first instance of this tactic — the women of the Cimbri, in the Battle of Vercellae against Gaius Marius, were stationed in a line of wagons and acted as a last line of defence.[33] Ariovistus of the Suebi is reported to have done the same thing in his battle against Julius Caesar.[34] Tacitus reports that "according to one report almost eighty thousand Britons fell" compared with only four hundred Romans.

According to Tacitus in his Annals, Boudica poisoned herself, though in the Agricola which was written almost twenty years prior he mentions nothing of suicide and attributes the end of the revolt to socordia ("indolence"); Dio says she fell sick and died and then was given a lavish burial; though this may be a convenient way to remove her from the story. Considering Dio must have read Tacitus, it is worth noting he mentions nothing about suicide (which was also how Postumus and Nero ended their lives).

Postumus, on hearing of the Roman victory, fell on his sword. Catus Decianus, who had fled to Gaul, was replaced by Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus. Suetonius conducted punitive operations, but criticism by Classicianus led to an investigation headed by Nero's freedman Polyclitus. Fearing Suetonius's actions would provoke further rebellion, Nero replaced the governor with the more conciliatory Publius Petronius Turpilianus.[35] The historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus tells us the crisis had almost persuaded Nero to abandon Britain.[36] No historical records tell us what had happened to Boudica's two daughters; whether they had fallen in the battle or committed suicide by taking poison just like their mother is uncertain.

Location of her defeat

The location of Boudica's defeat is unknown. Most historians favour a site in the West Midlands, somewhere along the Roman road now known as Watling Street. Kevin K. Carroll suggests a site close to High Cross in Leicestershire, on the junction of Watling Street and the Fosse Way, which would have allowed the Legio II Augusta, based at Exeter, to rendezvous with the rest of Suetonius's forces, had they not failed to do so.[37] Manduessedum (Mancetter), near the modern town of Atherstone in Warwickshire, has also been suggested,[38] as has "The Rampart" near Messing in Essex, according to legend.[39] More recently, a discovery of Roman artefacts in Kings Norton close to Metchley Camp has suggested another possibility,[40] and a thorough examination of a stretch of Watling Street between St. Albans, Boudica's last known location, and the Fosse Way junction has suggested the Cuttle Mill area of Paulerspury in Northamptonshire, which has topography very closely matching that described by Tacitus of the scene of the battle.[41]

In 2009 it was suggested that the Iceni were returning to East Anglia along the Icknield Way when they encountered the Roman army in the vicinity of Arbury Bank, Hertfordshire.[42] In March 2010, evidence was published suggesting the site may be located at Church Stowe, Northamptonshire.[43]

Historical sources

Tacitus, the most important Roman historian of this period, took a particular interest in Britain as his father-in-law Gnaeus Julius Agricola served there three times (and was the subject of his first book). Agricola was a military tribune under Suetonius Paulinus, which almost certainly gave Tacitus an eyewitness source for Boudica's revolt. Cassius Dio's account is only known from an epitome, and his sources are uncertain. He is generally agreed to have based his account on that of Tacitus, but he simplifies the sequence of events and adds details, such as the calling in of loans, that Tacitus does not mention.

Gildas, in his 6th century De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, may have been alluding to Boudica when he wrote "A treacherous lioness butchered the governors who had been left to give fuller voice and strength to the endeavours of Roman rule".[4]

Cultural depictions

Boudica and King's Cross

The area of King's Cross, London was previously a village known as Battle Bridge which was an ancient crossing of the River Fleet. The original name of the bridge was Broad Ford Bridge.

The name "Battle Bridge" led to a tradition that this was the site of a major battle between the Romans and the Iceni tribe led by Boudica.[44] The tradition is not supported by any historical evidence and is rejected by modern historians. However, Lewis Spence's 1937 book Boadicea — warrior queen of the Britons went so far as to include a map showing the positions of the opposing armies. There is a belief that she was buried between platforms 9 and 10 in King's Cross station in London, England. There is no evidence for this and it is probably a post-World War II invention.[45]

History and literature

By the Middle Ages Boudica was forgotten. She makes no appearance in Bede's work, the Historia Brittonum, the Mabinogion or Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain. But the rediscovery of the works of Tacitus during the Renaissance allowed Polydore Vergil to reintroduce her into British history as "Voadicea" in 1534.[46] Raphael Holinshed also included her story in his Chronicles (1577), based on Tacitus and Dio,[47] and inspired Shakespeare's younger contemporaries Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher to write a play, Bonduca, in 1610.[11] William Cowper wrote a popular poem, "Boadicea, an ode", in 1782.[12]

It was in the Victorian era that Boudica's fame took on legendary proportions as Queen Victoria came to be seen as Boudica's "namesake", their names being identical in meaning. Victoria's Poet Laureate, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, wrote a poem, "Boadicea", and several ships were named after her.[48]

Art

- The artwork The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago features a place setting for Boudica.[49]

Audio dramas

- The Big Finish Productions Doctor Who audio play The Wrath of the Iceni (2012), starring Tom Baker, takes place during Boudica's uprising against the Romans. Boudica is portrayed by British actress Ella Kenion.[50]

- Heirloom Audio Productions' audio theater adaption of G.A. Henty's novel, Beric the Briton, starring Brian Blessed, Brian Cox, and John Rhys-Davies features Queen Boadicea during the first portion of the drama. Her character is played by British actress, Honeysuckle Weeks.

Comics

She has also appeared in several comic book series, including:

- Sláine, which featured two runs, titled "Demon Killer" and "Queen of Witches" giving a free interpretation of Boudica's story

- The DC Comics character Boodikka, a member of the Green Lantern Corps, was named after Boudica.

Films

Boudica has been the subject of multiple films:

- Boadicea (1927) is a feature film, wherein she was portrayed by Phyllis Neilson-Terry,[51]

- The Viking Queen (1967) is a Hammer Films adventure movie set in ancient Britain, in which the role of Queen Salina is based upon the historical figure of Boudica.

- Boudica (2003; Warrior Queen in the US) is a UK TV film written by Andrew Davies and starring Alex Kingston as Boudica.[52]

- A History Channel documentary production is entitled Warrior Queen Boudica (2006).

Games

- In Civilization II, Civilization IV: Beyond the Sword and Civilization V: Gods & Kings, Boudicca is leader of the Celtic tribe.

- She appears as a character in the heavily fictionalized 2013 video game Ryse: Son of Rome.

- She appears in the tutorial of Rise of Nations.

Multimedia fiction

- In the fictional world of Ghosts of Albion, Queen Bodicea is one of three Ghosts who once were mystical protectors of Albion and assists the current protectors with advice and knowledge.

Music

- Irish singer and musician Enya has a song titled "Boadicea" on her first album Enya (also released as The Celts). The song was later sampled by various other artists.

Novels

Boudica's story is the subject of several novels, including books by J. F. Broxholme (a pseudonym of Duncan Kyle), Pauline Gedge, Alan Gold, Mary Mackie, Diana L. Paxson, Simon Scarrow, Manda Scott, George Shipway, Rosemary Sutcliff, and David Wishart.

- In Chapter XXI of Lindsey Davis' first Falco mystery, The Silver Pigs, Falco briefly recounts the story of the rebellion from his perspective, having served in the Second legion of the Roman army, under the "peabrained" Camp Prefect, Poenius Postumus. Throughout the book, he references the shame of having served under that illustrious leader and of being involved in that event.

- She plays a central role in the first part of G. A. Henty's novel Beric the Briton

- In The Mauritius Command by Patrick O'Brian, the fourth novel of the Aubrey-Maturin series, Jack Aubrey is given command of the HMS Boadicea.

- Tim Powers' vampire novel Hide Me Among the Graves (2012) depicts Boadicea as one of the two head vampires menacing Victorian Europe.

- Henry Treece's children's novel, The Queen's Brooch, is set during her rebellion.

- One of the viewpoint characters of Ian Watson's novel Oracle is an eyewitness to her defeat.

- In Harry Turtledove's alternate history novel Ruled Britannia, Boudicca is the subject of a play written by William Shakespeare to incite the people of Britain to revolt against Spanish conquerors.

Statue

.jpg)

A statue of Boudica with her daughters in her war chariot (ahistorically furnished with scythes after the Persian fashion) was executed by Thomas Thornycroft over the 1850s and 1860s with the encouragement of Prince Albert, who lent his horses for use as models.[53] Thornycroft exhibited the head separately in 1864. It was cast in bronze in 1902, 17 years after Thornycroft's death, by his son Sir John, who presented it to the London County Council. They erected it on a plinth on the Victoria Embankment next to Westminster Bridge and the Houses of Parliament, inscribed with the following lines from Cowper's poem:

Regions Caesar never knew

Thy posterity shall sway.

Ironically, the great anti-imperialist rebel was now identified with the head of the British Empire, and her statue[54] stood guard over the city she razed to the ground.[13]

Television

Series

- Boudicca is a character in the animated series Gargoyles.[55]

- She was the subject of a 1978 British TV series, Warrior Queen, starring Siân Phillips as Boudica.

Episodes

- The British television series Bonekickers, dedicated an hour to Boudica in the episode named "The Eternal Fire" (July 2008).[56] Various female politicians, including former Prime Minister of New Zealand Helen Clark, have been called Boadicea.[57]

- Jennifer Ward-Lealand portrayed Boudica in an episode of Xena: Warrior Princess titled "The Deliverer" (1997).

- Martha Howe-Douglas and Lorna Watson played Boudica in Horrible Histories.

- Kirsty Mitchell played Boudica in an episode of the History Channel's Barbarians Rising series titled "Revenge" (2016). The episode depicts Boudica as dying in battle after being run through by a Roman soldier, and one of her daughters being killed by a cavalryman, though the website for the series notes Tacitus' version of her suicide.[58]

Other cultural references

- In 2003, a long terminal repeat retrotransposon from the genome of the human blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni was named "Boudicca".[59][60] The Boudicca retrotransposon, a high-copy retroviral-like element, was the first mobile genetic element of this type to be discovered in S. mansoni.

See also

References

- ↑ John Davies (1993). A History of Wales. London, UK: Penguin. p. 28. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- ↑ "iam primum uxor eius Boudicca verberibus adfecta et filiae stupro violatae sunt" Tacitus, Annales 14.31

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Epitome of Book LXII , 2

- 1 2 Richard Hingley and Christina Unwin (15 June 2006). Boudica: Iron Age Warrior Queen (New ed.). Hambledon Continuum. pp. 44, 61. ISBN 978-1-85285-516-1.

- ↑ N. Davies (2008). The Isles: A History. p. 93.

- ↑ S. Dando-Collins (2012). Legions of Rome: The definitive history of every Roman legion.

- 1 2 Tacitus, Annals 14.33

- ↑ Tacitus, Agricola 14-16; Annals 14:29-39

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History 62:1-12

- ↑ The Gentleman's Magazine. W. Pickering. 1854. pp. 541–.

- 1 2 Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, Bonduca

- 1 2 William Cowper, Boadicea, an ode

- 1 2 Graham Webster (1978). Boudica: The British Revolt against Rome AD 60.

- ↑ Guy de la Bédoyère. The Roman Army in Britain. Retrieved 5 July 2005.

- ↑ Kenneth Jackson (1979). "Queen Boudica?". Britannia. 10: 255. doi:10.2307/526060.

- ↑ Boudicca. Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. (Retrieved 20 December 2007).

- ↑ Sir John Rhys (1908). Early Britain, Celtic Britain. General Literature Committee: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (Great Britain). p. 284. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ Peter Keegan. "Boudica, Cartimandua, Messalina and Agrippina the Younger. Independent Women of Power and the Gendered Rhetoric of Roman History". academia.edu. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ The term xanthotrichos translated in this passage as red–brown or tawny can also mean auburn, or a shade short of brown, but most translators now agree a colour in between light and browny red — tawny — Carolyn D. Williams (2009). Boudica and her stories: narrative transformations of a warrior queen. University of Delaware Press. p. 62.

- ↑ Tacitus, The Annals, 12.31-32

- ↑ "Boudica". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- 1 2 Tacitus, The Annals, 14.31

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History, 62.2

- ↑ Tacitus, The Annals, 14.32

- ↑ Tacitus, Agricola 15

- ↑ Jason Burke (3 December 2000). "Dig uncovers Boudicca's brutal streak". The Observer. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ "Haverhill From the Iron Age to 1899". St. Edmundsbury Borough Council. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ George Patrick Welch (1963). Britannia: The Roman Conquest & Occupation of Britain. p. 107.

- ↑ Maev Kennedy. "Roman skulls found during Crossrail dig in London may be Boudicca victims". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 14.34

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 14.37

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 14.32

- ↑ Florus, Epitome of Roman History 1.38

- ↑ Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 1.51

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 14.39

- ↑ Suetonius, Nero 18, 39-40

- ↑ Kevin K. Carroll (1979). "The Date of Boudicca's Revolt". Britannia. 10: 197–202. doi:10.2307/526056.

- ↑ Sheppard Frere (1987). Britannia: A History of Roman Britain. p. 73.

- ↑ "Messing Village". Messing-cum-Inworth Community Website.

- ↑ "Is Boudicca buried in Birmingham?". BBC News Online. 25 May 2006. Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- ↑ "モバイル版". paulerspury.org. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010.

- ↑ Grahame Appleby (2009). "The Boudican Revolt: Countdown to Defeat". Hertfordshire Archaeology and History. 16: 57–66. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ "Landscape Analysis and Appraisal Church Stowe, Northamptonshire, as a Candidate Site for the Battle of Watling Street" (PDF). craftpegg.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ↑ Walter Thornbury (1878). "Highbury, Upper Holloway and King's Cross". Old and New London: Volume 2. British History Online. pp. 273–279. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ "The "Warrior Queen" under Platform 9". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Polydore Vergil's English History, Book 2. pp. 69–72.

- ↑ Raphael Holinshed, Chronicles: History of England 4.9-13

- ↑ Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Boadicea

- ↑ Place Settings. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved on 2015-08-06.

- ↑ The Wrath of the Iceni at bigfinish.com.

- ↑ Boadicea (1927) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Warrior Queen (2003) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Macdonald, Sharon (1987). "Boadicea: Warrior, Mother, and Myth". Images of Women in Peace & War: Cross-Cultural & Historical Perspectives. London: Macmillan Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-299-11764-2.

- ↑ Corinne Field (30 April 2006). "Battlefield Britain — Boudicca's revolt against the Romans". Culture24. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

- ↑ Boudicca Archived 15 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. at The Gargoyles Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "Bonekickers" The Eternal Fire (TV Episode 2008) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Fran O'Sullivan (30 October 2008). "Gladiator v Boadicea: No contest?". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ↑ Sarah Pruitt (31 May 2016). "Who was Boudica? - Ask History". History.com. A&E Networks. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Copeland CS, Brindley PJ, Heyers O, Michael SF, Johnston DA, Williams DL, Ivens AC, Kalinna BH (June 2003). "Boudica, a retrovirus-like long terminal repeat retrotransposon from the genome of the human blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni". Journal of Virology. 77 (11): 6153–66. doi:10.1128/jvi.77.11.6153-6166.2003.

- ↑ Copeland CS, Heyers O, Kalinna BH, Bachmair A, Stadler PF, Hofacker IL, Brindley PJ (2004). "Structural and evolutionary analysis of the transcribed sequence of Boudicca, a Schistosoma mansoni retrotransposon". Gene. 329: 103–114. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.023.

Further reading

- Aldhouse-Green, M. (2006). Boudica Britannia: Rebel, War-Leader and Queen. Pearson Longman.

- de la Bédoyère, Guy (2003). "Bleeding from the Roman Rods: Boudica". Defying Rome: The Rebels of Roman Britain. Tempus: Stroud.

- Böckl, Manfred (2005). Die letzte Königin der Kelten [The last Queen of the Celts] (in German). Berlin: Aufbau Verlag.

- Cassius Dio Cocceianus (1914–1927). Dio's Roman History. 8. Earnest Cary trans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Collingridge, Vanessa (2004). Boudica. London: Ebury.

- Dudley, Donald R; Webster, Graham (1962). The Rebellion of Boudicca. London: Routledge.

- Fraser, Antonia (1988). The Warrior Queens. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Godsell, Andrew (2008). "Boadicea: A Woman's Resolve". Legends of British History. Wessex Publishing.

- Hingley, Richard; Unwin, Christina (2004). Boudica: Iron Age Warrior Queen. London: Hambledon and London.

- Roesch, Joseph E. (2006). Boudica, Queen of The Iceni. London: Robert Hale Ltd.

- Tacitus, Cornelius (1948). Tacitus on Britain and Germany. H. Mattingly trans. London: Penguin.

- Tacitus, Cornelius (1989). The Annals of Imperial Rome. M. Grant trans. London: Penguin.

- Taylor, John (1998). Tacitus and the Boudican Revolt. Dublin: Camvlos.

- Webster, Graham (1978). Boudica. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Cottrell, Leonard (1958). The Great Invasion. Evans Brothers Limited.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boudica. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Boadicea. |

- Boudica on In Our Time at the BBC. (listen now)

- Potter, T. W. "Boudicca (d. AD 60/61)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 October 2010. (subscription required (help)).. The first edition of this text is available as an article on Wikisource:

"Boadicea". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Boadicea". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - The Iceni Hoard at the British Museum

- James Grout: Boudica, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Trying to Rule Britannia; BBC; 6 August 2004

- Iceni at Roman-Britain.org

- Iceni at Romans in Britain

- Boadicea may have had her chips on site of McDonald's by Nick Britten

- PBS Boudica / Warrior Queen website

- Warrior queens and blind critics - article on the 2004 film King Arthur which discusses Boudica

- Project Continua: Biography of Boadicea

- Channel 4 History - In Boudica's Footsteps

-

"Boadicea". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (9th ed.). 1878.

"Boadicea". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (9th ed.). 1878.