Queen Elizabeth Way

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by the Ministry of Transportation of Ontario | ||||

| Length: | 139.1 km[1] (86.4 mi) | |||

| History: | Built: 1931 – October 14, 1956 | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| Fort Erie end: | Peace Bridge – Buffalo, NY, United States | |||

|

Red Hill Valley Parkway in Hamilton | ||||

| Toronto end: |

| |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

The Queen Elizabeth Way (QEW) is a 400-series highway in the Canadian province of Ontario linking Toronto with the Niagara Peninsula and Buffalo, New York. The freeway begins at the Peace Bridge in Fort Erie and travels 139.1 kilometres (86.4 mi) around the western shore of Lake Ontario, ending at Highway 427. The physical highway, however, continues as the Gardiner Expressway into downtown Toronto. The QEW is one of Ontario's busiest highways, with an average of close to 200,000 vehicles per day on some sections. Major highway junctions are located at Highway 420 in Niagara Falls, Highway 405 in Niagara-on-the-Lake and Highway 406 in St. Catharines, the Red Hill Valley Parkway in Hamilton, Highway 403 and Highway 407 in Burlington, Highway 403 at the Oakville–Mississauga boundary and Highway 427 in Etobicoke. Within the Regional Municipality of Halton, the QEW is signed concurrently with Highway 403.

The history of the QEW dates back to 1931, when work began to widen the Middle Road in a similar fashion to the nearby Dundas Highway and Lakeshore Road as a relief project during the Great Depression. Following the 1934 provincial election, Ontario Minister of Highways Thomas McQuesten and his deputy minister Robert Melville Smith changed the design to be similar to the autobahns of Germany, dividing the opposite directions of travel and using grade-separated interchanges at major crossroads. When it was initially opened to traffic in 1937, it was the first intercity divided highway in North America and featured the longest stretch of consistent illumination in the world. While not a true freeway at the time, it was gradually upgraded, widened and modernized beginning in the 1950s, more or less taking on its current form by 1975. Since then, various projects have continued to widen the route. In 1997, the provincial government turned over the responsibility for the section of the QEW between Highway 427 and the Humber River to the City of Toronto. This section was subsequently redesignated as part of the Gardiner Expressway.

Name and signage

The Queen Elizabeth Way was named for the wife of King George VI who would later become known as Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. It is sometimes referred to as the Queen E.[2] In 1939, the royal couple toured Canada and the United States in part to bolster support for the United Kingdom in anticipation of war with Nazi Germany, and also to mark George VI's coronation. The highway received its name to commemorate the visit; it was unveiled on June 7 as the King and Queen drove across the Henley Creek bridge in St. Catharines. Originally, the entire length of the highway featured stylized light standards with the letters "ER", the Royal Cypher for Elizabeth Regina, the Latin equivalent to "Queen Elizabeth". While mostly removed, they remain in place on three bridges along the route of the highway: in Mississauga over the Credit River, in Oakville over Bronte Creek, and in St. Catharines over Twelve Mile Creek. A short section of Highway 420 and its extension Falls Avenue in Niagara Falls had replicas of these light standards installed in 2002.[3]

The markers identifying the QEW have always used blue lettering on a yellow background instead of the black-on-white scheme used on other provincial highway markers. They originally showed the highway's full name only in small letters, with the large script letters "ER" placed where the highway number is on other signs. In 1955, these were changed to the current design, with the lettering "QEW".[4] Although the QEW has no posted highway number, it is considered to be part of the Province of Ontario's 400-series highway network.[5] The Ministry of Transportation of Ontario designates the QEW as Highway 451 for internal, administrative purposes.[6]

A monument was originally located in the highway median at the Toronto terminus of the highway, dedicated to the 1939 visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth and known as the Lucky Lion. Carved on-site under the direction of Frances Loring for C$12,000 (in 1940, $190,000 adjusted for inflation), it consisted of a column with a crown at the top and a lion at the base. The monument was removed in 1972 in order to accommodate widening of the original QEW, and relocated in August 1975 to the nearby Sir Casimir Gzowski Park along Lake Ontario, on the east side of the Humber River.[7]

Route description

The QEW is a 139 km (86 mi) route that travels from the Peace Bridge – which connects Fort Erie with Buffalo, New York – to Toronto, the economic hub of the province. The freeway circles the western lakehead of Lake Ontario, cutting through Niagara Falls, St. Catharines, Hamilton, Burlington, Oakville and Mississauga en route.[8] A 22 km (14 mi) portion of the freeway is signed concurrently with Highway 403.[1] Unlike other provincial highways in Ontario, the QEW is directionally signed using locations along the route as opposed to cardinal directions. Driving towards Toronto, the route is signed as "QEW Toronto" throughout its length. In the opposing direction, it is signed as "QEW Hamilton", "QEW Niagara" and "QEW Fort Erie" depending on the location.[4]

Fort Erie–St. Catharines

The Queen Elizabeth Way begins at the foot of the Peace Bridge, which crosses the border with the United States and connects the QEW with I-190 in Buffalo, New York. A customs booth is located between the bridge and the freeway, beyond which a toll is charged to Canada-bound drivers. West of there, access is provided to nearby Highway 3 and the Niagara Parkway. Through customs, the freeway proper begins, immediately curving northwest. Within the town of Fort Erie, interchanges provide access to and from the freeway at Central Avenue, Concession Road, Thompson Road, Gilmore Road and Bowen Road. While there is some urban development at the beginning of the freeway, the majority of the first 25 km (16 mi) are located within lowland forests. Numerous creeks flow through these forests, often flooding them. The Willoughby Marsh Conservation Area lies southwest of the freeway approximately 10 km (6.2 mi) south of Niagara Falls. After an interchange with Lyons Creek Road, the freeway curves northward.[8]

After crossing the Welland River, the original route of the Welland Canal, the freeway exits the forests and enters agricultural land surrounding the suburbs of Niagara Falls, which the highway enters north of the McLeod Road interchange. Within the city, Highway 420 meets the QEW at a large stack interchange, which replaced the former Lundy's Lane / Highway 20 interchange. Exiting the northern fringe of the city, the freeway curves northwest and begins to descend through the Niagara Escarpment, a World Biosphere Reserve. Highway 405, also known as the General Brock Parkway, merges with the QEW along the short rural stretch between Niagara Falls and St. Catharines. While there is no Toronto-bound access, Niagara-bound drivers can follow Highway 405 to Lewiston, New York. The QEW continues west into St. Catharines.[8]

St. Catharines–Burlington

As the Queen Elizabeth Way enters St. Catharines, it ascends onto the Garden City Skyway to cross the Welland Canal. The 2.2 km (1.4 mi) structure replaced the lift bridge located south of it, one of two major bottlenecks prior to the early 1960s, and is one of two high-level skyways along the length of the route. As the QEW was the first long distance freeway in North America, several modern engineering concepts were not considered and further expansion of the highway is inhibited by the proximity of properties throughout most of its length. Consequently, most of the route beyond the Welland Canal is sandwiched between service roads which provide access to and from the QEW as well as to local businesses and residences. After passing the Ontario Street (Regional Road 42) interchange, the freeway crosses Martindale Pond, which forms the mouth of Twelve Mile Creek. West of the crossing is an interchange with Highway 406, which travels south to Welland, after which the QEW crosses out of St. Catharines and into the town of Lincoln at Fifteen Mile Creek.[9]

Throughout Lincoln, the QEW travels along the Lake Ontario shoreline through the Niagara Fruit Belt; numerous wineries line the south side of the freeway. Interchanges at Victoria Road (Regional Road 24) and Ontario Street (Regional Road 18) provide access to the communities of Vineland and Beamsville, respectively. The latter encroaches upon the south side of the QEW, interrupting the otherwise agricultural surroundings of the highway in Lincoln. Immediately east of the Bartlett Avenue interchange, the freeway enters Grimsby, where it becomes sandwiched between the Niagara Escarpment and Lake Ontario. The route passes under three overpasses that have remained unchanged since the highway was built: Maple Avenue, Ontario Street and Christie Street, all served by a single diamond interchange. South of the 50 Point Conservation Area, the freeway exits Niagara Region and enters the city of Hamilton.[10]

Within Hamilton, the highway passes almost entirely within an industrial park, with interchanges at 50 Road, Fruitland Road and Centennial Parkway (formerly Highway 20). The third is intertwined with the Red Hill Valley Parkway interchange, completed in 2009. From here, the freeway curves northwest onto Burlington Beach and begins to ascend the Burlington Bay James N. Allan Skyway Bridge, the second high-level bridge along the route. As it crosses over the entrance to Hamilton Harbour, the freeway enters the Regional Municipality of Halton and descends into the city of Burlington.[9]

Burlington–Toronto

After descending into Burlington, the QEW crosses former Highway 2 before it encounters the Freeman Interchange, opened in 1958 to allow construction of Highway 403 and expanded in 1999 to accommodate Highway 407. The freeway curves to the east, becoming concurrent with Highway 403 through Burlington and Oakville within Halton Region. The two routes travel east straight though a commercial office area. Service roads reappear through this stretch to serve businesses fronting the highway. The segment includes high-occupancy vehicle lanes, opened in 2011, which required the construction of a second structure over Sixteen Mile Creek. In the eastern end of Oakville, the route curves northeast, passing the Ford Motor Assembly Plant. Highway 403 diverges and travels north as the QEW curves back to the east and enters Mississauga and Peel Region.[8]

Within Mississauga, the freeway encounters its narrowest right-of-way, sandwiched between residential subdivisions on either side that prevent further expansion of the busy route. It crosses the Credit River Valley, where a second bridge is currently under construction. The segment east of the Credit River is being examined for expansion possibilities, but like the previous section there is little room for more lanes without property acquisition. After crossing Etobicoke Creek, which forms the boundary between Mississauga / Peel Region and Toronto, the route curves eastward to meet Highway 427 at a large sprawling interchange.[8] The QEW formerly continued beyond this interchange to the old Toronto city limits at the Humber River; this section was downloaded from provincial to municipal ownership on April 1, 1997, and became part of the Gardiner Expressway.[11]

History

The Middle Road

We need this new highway to relieve traffic congestion in the metro Toronto .

As automobile use in southern Ontario grew in the early 20th century, road design and construction advanced significantly. A major issue faced by planners was the improvement of the routes connecting Toronto and Hamilton, which were consistently overburdened by the growing traffic levels.[13] Following frequent erosion of the former macadamized Lakeshore Road,[14] a cement road known as the Toronto–Hamilton Highway was proposed in January 1914.[15] The highway was designed to run along the lake shore, instead of Dundas Street to the north, because the numerous hills encountered along Dundas would have increased costs without improving accessibility. Middle Road, a dirt lane named because of its position between the two, was not considered since Lakeshore and Dundas were both overcrowded and in need of serious repairs.[16] Construction began on November 8, 1914, but dragged on throughout the ongoing war.[13] It was formally opened on November 24, 1917,[14] 5.5 m (18 ft) wide and nearly 64 km (40 mi) long. It was the first concrete road in Ontario, as well as one of the longest stretches of concrete road between two cities in the world.[17]

Over the next decade, vehicle usage increased substantially, and by 1920 Lakeshore Road was again highly congested on weekends.[18] In response, the Department of Highways examined improving another road between Toronto and Hamilton. The road was to be more than twice the width of Lakeshore Road at 12 m (39 ft) and would carry two lanes of traffic in either direction.[19] Construction on what was then known as the Queen Street Extension west of Toronto began in early 1931 as a depression-relief project.[20]

Before the highway could be completed, Thomas McQuesten was appointed the new minister of the Department of Highways, with Robert Melville Smith as deputy minister, following the 1934 provincial elections.[21] Smith, inspired by the German autobahns—new "dual-lane divided highways"—modified the design for Ontario roads,[22] and McQuesten ordered that the Middle Road be converted into this new form of highway.[23][24][25] A 40 m (130 ft) right-of-way was purchased along the Middle Road and construction began to convert the existing sections to a divided highway. Work also began on Canada's first interchange at Highway 10.[19]

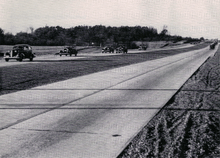

By the end of 1937, the Middle Road was open between Toronto and Burlington, and would soon connect with what was first known as the Hamilton–Niagara Falls Highway. When it opened, it was the first intercity divided highway in North America[Note 1] and boasted the longest continuous stretch of illumination in the world until World War II.[26][27] It soon came time to name the new highway, and an upcoming visit by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth proved to be the focal point for a dedication ceremony. On June 7, 1939, the two royal family members drove along the highway (which now connected to Niagara Falls) and passed through a light beam at the Henley Bridge in St. Catharines. This caused two Union Jacks to swing out, revealing a sign which read The Queen Elizabeth Way.[28]

However, the ceremony only designated the highway between St. Catharines and Niagara Falls. The remainder of the road was known by various names, including the Toronto–Burlington/Hamilton Highway and The New Middle Road Highway.[28]

The New Niagara Falls Highway

McQuesten also foresaw the financial opportunities that came with cross-border tourism and opening the "Ontario frontier" to Americans. In 1937, construction began on a new dual highway along the bottom of the Niagara Escarpment. This route was originally known as the New Niagara Falls Highway, but it was intended to connect with the Middle Road on the opposing shore of Lake Ontario.[29] Work began at the end of March to grade the route between Stoney Creek and Jordan.[30]

The prospect of removing hundreds of acres of farmland did not sit well with many, especially farmers in the path of the new highway. Rumours spread that the prices paid for land were to be well below market value, and local protests erupted throughout the summer. However, the purpose of the new highway was to replace the congested, winding and hilly route of Highway 8 along the escarpment; several groups of collisions that summer gradually persuaded the public in support of the new highway. By the autumn, 340 acres (140 ha) of fruitland were cleared to make way for the route.[31]

Over the next two years, numerous bridges and cloverleaf interchanges along the new highway were constructed. In addition, a large traffic circle was built in Stoney Creek to connect with Highway 20. The majority of this structural work was completed before the royal visit in 1939. However, despite being opened to traffic between Stoney Creek and Jordan, the majority of the new route was gravelled. Over a ten-week period in the late spring and early summer of 1940, 58 km (36 mi) were paved, completing the four lane highway between Hamilton and Niagara. On August 23, 1940, McQuesten cut a ribbon at the Henley Bridge in St. Catharines and officially declared the Queen Elizabeth Way open between Toronto and Niagara Falls.[32] Construction towards Fort Erie continued, but the ongoing war would delay its completion for some time. As an interim measure, the unpaved highway was opened during the summer of 1941. Two lanes of pavement were laid in 1946, but the four-lane highway was not fully paved until 1956. The completed QEW was officially opened on October 14 of that year, completing the envisioned highway 25 years after work had begun.[33]

Conversion to freeway

1950s – Control of access

Despite some modern infrastructure, including traffic circles, interchanges, and some grade-separations, the majority of the new superhighway was not controlled-access. This meant that existing farmers and homeowners along several segments that were once concession roads were permitted to build driveways and entrances onto the road. In addition, the majority of the crossroads encountered along the route were at-grade intersections. This combined with the ever-increasing number of automobiles, traffic jams, accidents and deteriorating pavement led the Department of Highways to report that it had begun "salvaging" the QEW in their 1953 annual report.[34]

The first new interchange opened at Dixie Road in 1953, beginning a seven-year program to make the Hamilton–Toronto section into a full-fledged freeway.[35] Over the next three years, the route was improved west to Highway 10 (Hurontario Street). This work was completed in early 1956. Service roads were installed and 13 intersections eliminated, resulting in a 50% reduction of the accident rate along that section.[36] In Toronto, work began in 1955 to construct the Gardiner Expressway, which would tie in with the end of the QEW.[37] The first section of the Gardiner, connecting the QEW to Jameson Avenue, was officially opened by mayor Fred Gardiner and Premier Leslie Frost on August 8, 1958[38] Work was also underway on the Toronto Bypass, involving the upgrade of Highway 27 to a freeway between the QEW and the new Highway 401. Construction began in 1953,[39] and included an upgrade of the cloverleaf interchange with the QEW with larger loop ramps. This interchange would become one of the worst bottlenecks in the province a decade after its completion, according to Highways Minister Charles MacNaughton.[40]

On September 11, 1957, construction began to widen the QEW to six lanes between Highway 27 and the Humber River. It was completed by December 1958,[41] as were interchanges with Mississauga Road and Kerr Street.[42] Service roads allowed engineers to separate local access from the highway and avoid space-consuming interchanges in many places.[34] As such, interchanges were only opened at Bronte Road (then Highway 25), Kerr Street, Royal Windsor Drive (then Highway 122), Erin Mills Parkway, Mississauga Road, Hurontario Street (then Highway 10), Cawthra Road, Dixie Road, and Highway 27.

The Skyways

Two major projects were ongoing near Burlington at this point. On April 29, 1952, the W.E. Fitzgerald struck the two lane lift-bridge at the entrance to Hamilton Harbour.[43] Damage to the crossing resulted in the closure of the QEW until a temporary bridge was erected. To remedy what was becoming a major delay and hazard, the Department of Highways began planning a high-level bridge to cross the shipping channel. To provide better access to the new structure as well as the proposed Chedoke Expressway, construction began on the Freeman Diversion, bypassing the old trumpet interchange and creating a new three-level stack. Work on both proceeded over the next six years.[44]

The Freeman Diversion opened to traffic in August 1958,[45] with the old route becoming an eastward extension of Plains Road.[8] The 2,700-metre-long (8,900 ft) four-lane skyway was opened to traffic by Leslie Frost two months later on October 30. Although it greatly reduced traffic delays, it was not without controversy due to its height, cost, tolling, and most especially its name. Residents in Burlington demanded it be named the Burlington Skyway, while Hamilton residents countered with the Hamilton Skyway. As a compromise, the Thomas B. McQuesten Skyway was proposed. However, the provincial government had the final say in the matter, and opted to name it the Burlington Bay Skyway. Tolls were collected beginning on November 10.[44]

Elsewhere, in St. Catharines, planning was already advanced on a second skyway to cross the Welland Canal. The Homer Lift Bridge, a longstanding feature along Highway 8, was another point where the QEW narrowed to two lanes and traffic faced regular delays. Construction of the Homer Skyway, as it was tentatively known, began in July 1960 and progressed over the following three years.[44][46] The $20 million (in 1963, $158,000,000 adjusted for inflation) structure was officially opened by Premier John Robarts on November 15, 1963. However, traffic had already been flowing on the 2,200-metre-long (7,200 ft) bridge since October 18.[47] As with the Burlington Bay Skyway, tolls were collected on the new bridge. However, the name was almost unanimously chosen by St. Catharines residents to be the Garden City Skyway.[48] The collection of tolls on both skyways continued until December 28, 1973.[49]

1960s and 1970s – Expansion and new interchanges

On September 15, 1960, the Shook's Hill interchange, a unique rotary junction, was completed. It was opened to traffic the following day, and completed the program to make the QEW a freeway between Burlington and Toronto.[50][51] A final project, to reconstruct the intersection with Brant Street into an interchange, was carried out in 1964 and made the QEW a freeway between Hamilton and Toronto.[52]

By 1963, work was underway to improve the Niagara Falls–Hamilton stretch of the QEW into a controlled-access highway.[53] At the end of 1966, the QEW was six lanes wide through Mississauga and Toronto, as well as between the Freeman Interchange and east of Brant Street.[54] This six-laning was extended west from Ninth Line to Kerr Street by 1968. The remaining section of four-lane highway along the Burlington to Toronto stretch, between Brant Street and Kerr Street, was reconstructed beginning in 1970 and completed by 1972.[55][56]

The late 1960s and early 1970s also saw the complete reconstruction of three important interchanges: The Rainbow Bridge Approach (later Highway 420) in Niagara Falls, Highway 20 (Centennial Parkway) in Hamilton and Highway 27 in Toronto. The former two were traffic circles in place since the QEW was opened in 1940. The third was a large cloverleaf interchange that had become outdated with the expansion of Highway 27 to ten lanes throughout the 1960s. The connections with the Rainbow Bridge Approach and with Highway 27 required new massive high-speed interchanges to accommodate freeway–freeway traffic movements.[34][37]

The junction with Highway 27 was built over 48.5 ha (120 acres) and required the construction of 19 bridges and the equivalent of 42 km (26 mi) of two-lane roadway. Construction began in September 1968,[57] although preliminary work had been ongoing since 1966;[54] the interchange opened to traffic on November 14, 1969, and included an expansion of the QEW to ten lanes between what would become known as Highway 427 and Lake Shore Boulevard.[57][58] Construction of the three-level stack interchange between the QEW and Rainbow Bridge Approach began in 1971. This removed the two traffic circles along the approach at the QEW and Dorchester Road.[59] The interchange between the QEW and Lundy's Lane (Highway 20) was also removed; instead, the new stack interchange provided access to Montrose Road.[60] The work was completed by April 1972, at which point the Rainbow Bridge Approach was designated as Highway 420.[61] Planning for the removal of the Stoney Creek traffic circle was completed by 1970,[55] and reconstruction began in 1974.[62] This involved the removal of a rail line which crossed through the circle, and was the demise of one of two major features along the route.[34][37] The new interchange opened in 1978,[63] completing the transformation of the QEW into a controlled-access highway.[62]

During the late 1970s, construction was carried out on several new interchanges between Hamilton and Toronto. A new interchange at Dorval Drive and Trafalgar Road replaced the one at Kerr Street. In Mississauga, work commenced at Cawthra Road, while in Burlington a new interchange was built at Appleby Line.[64][65]

1980s to 1997 - Growing capacity

Now functioning as a freeway, the QEW was already overburdened by the ever-increasing number of vehicles. The Burlington Bay Skyway, the lone four-lane link on the route between Hamilton and Toronto, was initially designed to handle 50,000 vehicles daily, but by 1973 there were 60,000 vehicles crossing it. Preliminary work on a second parallel structure began a decade later in 1983.[66] In July of that year, Transportation Minister James Snow broke ground for the new bridge.[48] Construction was carried out over two years, and the twinned structure was opened on October 11, 1985.[49] It was named the James N. Allan Skyway, in honour of James Allan, Minister of Highways during construction of the original skyway. The new name was not well received by locals, and debate erupted once again whilst the original bridge was closed and repaired for several years.[48] It reopened on August 22, 1988,[49] with Toronto-bound traffic crossing the original bridge. The twin structure was renamed the Burlington Bay James N. Allan Skyway, though it is commonly referred to as simply the Burlington Skyway.[48]

Alongside the twinning of the skyway, the QEW was widened to eight lanes between Burlington Street in Hamilton and Northshore Boulevard (then Highway 2) in Burlington, and to six lanes north to the Freeman Interchange and south to Centennial Parkway. A variable lighting system, changeable message signs and traffic cameras were added to create a new traffic-management system called COMPASS. Modern interchanges were constructed with Burlington Street, Northshore Boulevard, Fairview Street and Brant Street, and the interchange with Plains Road was removed. Eastport Drive was built at the same time to relieve traffic on Beach Boulevard. This work was completed between late 1984 and 1990.[67][68]

With the expanded capacity of the skyway, and the unanticipated traffic volumes on Highway 403, the Freeman Interchange was now faced with a capacity problem. To resolve this, the renamed Ministry of Transportation began planning on Highway 403 between Burlington and Mississauga;[69] this right-of-way would be sold to the 407 ETR consortium in 1995 and built as part of that route.[70] Work began in August 1991 to rebuild the interchange and add a fourth leg. The rebuilt interchange was opened on October 23, 1993; the first sod for what would open as Highway 407 was turned that day.[71]

Budgetary restraints in the 1990s forced the provincial government to sell off or download many highways to lower levels of government, or, in the case of Highway 407, to a private consortium.[72] As part of recommendations, the QEW east of Highway 427 to the Humber River was transferred to the responsibility of the City of Toronto. The transfer took place on April 1, 1997.[11] The city subsequently renamed it as part of the Gardiner Expressway.[73]

Recent work

Beginning in May 1999, the grade-separated traffic circle junction with Erin Mills Parkway and Southdown Road, which dated back to the early 1960s, was completely reconstructed as a standard parclo A4 interchange; it was reopened in 2001.[74] The nearby Hurontario Street interchange was upgraded from a cloverleaf to a parclo A4 on the south side and a diamond interchange on the north side. Work was completed in 2010.[75]

The Red Hill Valley Parkway project, which opened on November 16, 2007, added a significant new interchange to the QEW.[76] The ramp to the southbound parkway did not open until December 2008.[77] As part of this project, the Burlington Street and Centennial Parkway interchanges were reconstructed, and the QEW widened to eight lanes from Burlington Street to Centennial Parkway. Construction was completed in 2009.[78]

The highway was widened to permit an additional HOV lane in either direction between Guelph Line and Trafalgar Road starting in 2007. These lanes were opened to traffic on November 29, 2010.[79] In 2005,[80] work began to widen the QEW through St. Catharines from Highway 406 to the Garden City Skyway. This work was completed on August 26, 2011, at a cost of $186 million.[81]

High-occupancy toll lanes

On December 7, 2015, Ontario's Transportation Ministry announced that it was working on a plan to create permanent high-occupancy toll lanes (HOT) on a 16.5-kilometre (10.3 mi) stretch, in both ways, between Trafalgar Road in Oakville and Guelph Line in Burlington starting on September 15, 2016.[82] This would require vehicles with a single occupant to purchase a permit for such use. (A portion of Highway 427 would also have HOT lanes.) Vehicles that are classified as environmentally-friendly, and denoted with a green license plate, would not be required to pay when using the HOT lanes.[83] Prices for the permits had not yet been determined for this plan, described as a pilot project, said Transportation Minister Steven Del Duca during a press conference.[84]

Exit list

The following table lists the exits along the QEW. Exits are numbered from Fort Erie to Toronto.

| Division | Location | km[1] | Exit[8] | Destinations | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niagara | Fort Erie | 0.2 | International customs plaza; no exit number; no access from Central Avenue to Peace Bridge. Toll rates | |||

| 1.1 | 1 | Toronto-bound exit and Fort Erie-bound entrance | ||||

| 2.1 | 2 | Toronto-bound exit and Fort Erie-bound entrance | ||||

| Fort Erie-bound exit and Toronto-bound entrance | ||||||

| 4.6 | 5 | |||||

| 6.7 | 7 | |||||

| Fort Erie–Niagara Falls boundary | 12.2 | 12 | ||||

| Niagara Falls | 15.5 | 16 | ||||

| 22.1 | 21 | |||||

| 26.6 | 27 | |||||

| 29.5 | 30 | |||||

| 31.5 | 32 | |||||

| 34.0 | 34 | |||||

| Niagara-on-the-Lake | 36.5 | 37 | Niagara-bound exit and Toronto-bound entrance | |||

| 37.8 | 38 | |||||

| St. Catharines | 43.9 | 44 | ||||

| 45.6 | 46 | |||||

| 46.9 | 47 | |||||

| 47.7 | 48 | Toronto-bound exit and Niagara-bound entrance | ||||

| 48.4 | 49 | |||||

| 50.4 | 51 | |||||

| Lincoln | 54.7 | 55 | ||||

| 57.6 | 57 | |||||

| 64.3 | 64 | |||||

| Grimsby | 68.1 | 68 | ||||

| 70.6 | 71 | |||||

| 74.2 | 74 | |||||

| Hamilton | 77.8 | 78 | Regional Road 450 (Fifty Road) | |||

| 82.9 | 83 | Regional Road 455 (Fruitland Road) | ||||

| 88.1 | 88 | Regional Road 20 (Centennial Parkway) South Service Road |

Formerly Highway 20 | |||

| 89 | Red Hill Valley Parkway | |||||

| 89.8 | 89 | Nikola Tesla Boulevard | ||||

| 90 | Woodward Avenue | Niagara-bound exit and Toronto-bound entrance | ||||

| 93.8 | 93 | Eastport Drive (Highway 7189) | Toronto-bound exit and Niagara-bound entrance | |||

| Halton | Burlington | 97.1 | 97 | North Shore Boulevard, Eastport Drive | Formerly Highway 2 | |

| 99.5 | 99 | Plains Road, Fairview Street | Toronto-bound exit and Niagara-bound entrance | |||

| 100.5 | 100 | Toronto-bound exit and Niagara-bound entrance; toll highway | ||||

| Beginning of Highway 403 concurrency | ||||||

| 101.3 | 101 | Regional Road 18 (Brant Street) | Toronto-bound entrance | |||

| 103.2 | 102 | Regional Road 1 (Guelph Line) | ||||

| 105.2 | 105 | Walkers Line | ||||

| 107.3 | 107 | Regional Road 20 (Appleby Line) | ||||

| Burlington–Oakville boundary | 109.3 | 109 | Regional Road 21 (Burloak Drive) | |||

| Oakville | 110.9 | 110 | Service Road | Access removed in 2008 to accommodate widening of the QEW for HOV Lanes | ||

| 111.3 | 111 | Regional Road 25 (Bronte Road) – Milton | ||||

| 113.4 | 113 | 3rd Line | ||||

| 116.5 | 116 | Regional Road 17 (Dorval Drive) | ||||

| Kerr Street | Hamilton-bound exit only | |||||

| 118.6 | 118 | Regional Road 3 (Trafalgar Road) | ||||

| 120.0 | 119 | Royal Windsor Drive | Toronto-bound exit and Hamilton-bound entrance; formerly Highway 122 | |||

| 123.1 | 123 | Regional Road 13 (Ford Drive) | ||||

| End of Highway 403 concurrency; Toronto-bound exit and Hamilton-bound entrance | ||||||

| Halton–Peel boundary | Oakville–Mississauga boundary | 124.5 | 124 | Regional Road 19 (Winston Churchill Boulevard) | ||

| Peel | Mississauga | 126.6 | 126 | Regional Road 1 (Erin Mills Parkway) Southdown Road |

Southdown Road formerly Highway 122 | |

| 130.7 | 130 | Mississauga Road | ||||

| 132.7 | 132 | Hurontario Street | Formerly Highway 10 | |||

| 134.9 | 134 | Regional Road 17 (Cawthra Road) | ||||

| 136.7 | 136 | Regional Road 4 (Dixie Road) | Hamilton-bound exit and Toronto-bound entrance | |||

| Toronto | 138.5 | 138 | Evans Avenue, West Mall, Brown's Line | Toronto-bound exit and Hamilton-bound entrance | ||

| 139.1 | 139 | |||||

| Toronto | 140.5 | 140 | Kipling Avenue | Redesignated as an extension of the Gardiner Expressway April 1, 1997. Exit numbers were removed upon downloading to the City of Toronto. Exit numbers were subsequently reinstated by the City of Toronto in October 2016, and are a continuation of the kilometre-based numbering scheme west of Highway 427, but vary from the pre-1997 numbering. | ||

| 141.9 | 141 | Islington Avenue | ||||

| 143.1 | 143 | Park Lawn Road | ||||

| 145.3 | 145 | |||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||

In popular culture

As the principal travel route between Toronto and Buffalo, whenever sports teams from the two cities face each other (particularly the Sabres and Maple Leafs in the National Hockey League) the game or series is called as The Battle of the QEW.[85]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ While the Long Island Parkway and several similar roadways opened in the late twenties and early thirties, these parkways were designed to move traffic in and out of a city's downtown. The Middle Road was designed to provide travel between cities, and opened a year before the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the first U.S. highway to do this.

Sources

- 1 2 3 Ministry of Transportation of Ontario (2007). "Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) counts". Government of Ontario. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ Miller, Tim; Stancu, Henry (July 27, 2012). "The QEW: 75 Years and Counting". Wheels.ca. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, pp. 31–34.

- 1 2 Stamp 1987, p. 9.

- ↑ Walter, Karena (February 21, 2014). "Search Engine: Highway Mysteries Solved". The Niagara Falls Review. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ↑ Ministry of Transportation of Ontario. Ontario Provincial Standard Drawing 2001.110 (PDF) (Report). Government of Ontario. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, pp. 43–46.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ontario Back Road Atlas (Map). Cartography by MapArt. Peter Heiler. 2010. pp. 18–19, 24. § L28–U36. ISBN 978-1-55198-226-7.

- 1 2 Golden Horseshoe (Map). Cartography by MapArt. Peter Heiler. 2011. pp. 715, 716, 726. § L17–N28. ISBN 978-1-55198-877-1.

- ↑ Golden Horseshoe (Map). Cartography by MapArt. Peter Heiler. 2011. pp. 711–715. § E33–F42, K1–L17. ISBN 978-1-55198-877-1.

- 1 2 Highway Transfers List (Report). Ministry of Transportation of Ontario. April 1, 1997. p. 3.

- ↑ "Ontario to Bar All Gas Stands on Speedways". The Gazette. 167 (214). Montreal. September 7, 1938. pp. 1, 19. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- 1 2 Filey, Mike (November 20, 2011). "Road Pioneers of the Past". Life. The Toronto Sun. p. 44.

- 1 2 Emery & Ford 1967, pp. 179–182.

- ↑ "Toronto–Hamilton Highway Proposed". The Toronto World. January 22, 1914. p. 14. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ↑ Shragge & Bagnato 1984, p. 55.

- ↑ Shragge p. 55 "...the Toronto-to-Hamilton highway which, when completed in 1917, was both Ontario's first concrete highway and one of the longest such inter-city stretches in the world."

- ↑ "Increased Volume of Traffic". County And Suburbs. Toronto World. June 26, 1920. p. 7. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- 1 2 Shragge & Bagnato 1984, pp. 79–81.

- ↑ Filey 1994, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Shragge, John G. (2007). "Highway 401 – The Story". Archived from the original on March 28, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ "Hopes to Improve Roads". The Gazette. Montreal. February 18, 1936. p. 14. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ↑ English, Bob (March 16, 2006). "Remember That 'Little Four-Lane Freeway?'". Globe And Mail. Toronto. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

...the freeway concept was promoted by Hamiltonian Thomas B. McQuesten, then the highway minister. The Queen Elizabeth Way was already under construction, but McQuesten changed it into a dual-lane divided highway, based on Germany's new autobahns.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, p. 11.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, p. 47.

- 1 2 Filey, Mike (June 6, 2010). "A Royal Trip Around T.O.". Life. The Toronto Sun. Sun Media. p. 37.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, p. 25.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, p. 27.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, pp. 25–28.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, pp. 33–36.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, p. 49.

- 1 2 3 4 Stamp 1987, pp. 50, 54.

- ↑ "Division No. 6—Toronto". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. March 31, 1954. p. 61.

- ↑ "Accident Alley Crashes Reduced by 50 Per Cent". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. July 21, 1956. p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Stamp 1987, p. 56.

- ↑ "Frederick G. Gardiner $13,000,000 Super-Highway Opened Today By Premier Frost". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Clarke, W.A (March 31, 1954). "Report of the Chief Engineer". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. p. 12.

- ↑ "Six-Mile Stretch of Highway 27 Will Be Expanded to Six Lanes". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. May 4, 1965. p. 5.

- ↑ "Chronology". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. March 31, 1959. p. 267.

- ↑ "Construction Report – Central Area". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. March 31, 1959. p. 26.

- ↑ Blanchard, Douglas (April 30, 1952). "May Blow Up Bridge -- Expert". Toronto Daily Star. pp. 1–3.

- 1 2 3 Stamp 1987, pp. 59–61.

- ↑ AADT Traffic Volumes 1955–1969 And Traffic Collision Data 1967–1969. Department of Highways. 1969. p. 10.

- ↑ Shragge & Bagnato 1984, p. 81.

- ↑ "Chronology". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. March 31, 1964. p. 296.

- 1 2 3 4 Stamp 1987, pp. 61–62.

- 1 2 3 "Fast Facts from Hamilton's Past". MyHamilton. Archived from the original on September 5, 2006. Retrieved January 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Division No. 6 - Toronto". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. March 31, 1960. p. 84.

The construction of the [Shook's Hill] interchange will complete the facilities necessary for the complete control of access of the Queen Elizabeth Way between the Humber River and Highway 25

- ↑ "Chronology". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. March 31, 1961. p. 269.

- ↑ "Division No. 4 - Hamilton". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. March 31, 1965. p. 99.

- ↑ "Construction – Central Area". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. March 31, 1963. pp. 31–32.

- 1 2 "Summary of the Report". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways. March 31, 1967. p. xvi.

- 1 2 "Queen Elizabeth Way–Oakville–Fort Erie". Highway Construction Program (Report). Department of Highways. 1970–1971. p. xii.

- ↑ "Queen Elizabeth Way – Oakville to Fort Erie". Highway Construction Program (Report). Ministry of Transportation and Communications. 1971–1972. p. xii.

- 1 2 "Drivers Face Three More Years of QE-27-401 Motoring Misery". The Toronto Star. July 22, 1969. p. 43.

- ↑ "QE and 27 Interchange Opens Friday". The Toronto Star. November 13, 1969. p. 1.

- ↑ Stamp 1987, p. 65.

- ↑ Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by Cartography Section. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. 1977. South-Central Ontario inset.

- ↑ "Queen Elizabeth Way – Hamilton to Fort Erie". Highway Construction Program 1972-73 (Report). Ministry of Transportation and Communications. April 1972. p. xv.

- 1 2 Construction Program (Report). Ministry of Transportation and Communications. 1975–1976. p. xiii.

- ↑ "From Saltfleet to Stoney Creek". Virtual Museum of Canada. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ↑ Construction Program (Report). Ministry of Transportation and Communications. 1976–1977. p. XIII.

- ↑ Construction Program (Report). Ministry of Transportation and Communications. 1980–1981. p. XVI.

- ↑ Shragge & Bagnato 1984, p. 83.

- ↑ Provincial Highways Construction Projects (Report). Ministry of Transportation and Communications. 1985–1986. p. X. ISSN 0714-1149.

- ↑ Provincial Highways Construction Projects (Report). Ministry of Transportation and Communications. 1989–1990. p. 9. ISSN 0714-1149.

- ↑ Provincial Highways Construction Projects (Report). Ministry of Transportation and Communications. 1991–1992. p. 8. ISSN 0714-1149.

- ↑ Boyle, Theresa (April 1, 1995). "Rae Announces 407 Extension". News. The Toronto Star. p. A12.

Rae also announced yesterday that the province will ask for private-sector proposals to design and construct the Burlington–Oakville link of Highway 403 as part of Highway 407.

- ↑ Tait, Eleanor (October 23, 1993). "Sod Broken On QEW and Hwy. 403 Link". News. The Hamilton Spectator. p. T8.

- ↑ Schankula, Tina (November 18, 1997). Transfer of Responsibility for Provincial Highways to Municipalities (Report). Ontario Federation of Agriculture.

- ↑ "The Gardiner Expressway". Get Toronto Moving. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ Hicks, Kathleen A. (2003). Clarkson and its Many Corners (PDF). Mississauga Library System. p. 258. ISBN 0-9697873-4-0. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ↑ Ministry of Transportation of Ontario (2010). "2010 Completed Projects". Southern Highways Program 2011 to 2015 (PDF) (Report). Government of Ontario. p. 8. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Red Hill Opening Delayed". Local. The Hamilton Spectator. November 15, 2007. p. A4.

- ↑ De Lazzer, Rachel (November 13, 2008). "Ramp Delay Puts Pressure on Woodward". Local. The Hamilton Spectator. p. A4.

- ↑ Ministry of Transportation of Ontario (2010). "Red Hill Creek Expressway Interchange, QEW Burlington Street to Centennial Parkway". Southern Highways Program 2010–2014 (PDF) (Report). Government of Ontario. p. 6. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ↑ Ministry of Transportation (November 29, 2010). "HOV Lanes Open On QEW Between Burlington and Oakville". Government of Ontario. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ↑ Phillips, Carol (December 17, 2004). "QEW Widening Starts With $15.2m Bridges Project". The Hamilton Spectator. p. A7.

- ↑ "Queen Elizabeth Way Widening in St. Catharines, Ontario Complete". Daily Commercial News. August 26, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ↑ Edwards, Peter (June 23, 2016). "Toll Lanes Coming to QEW on Sept. 15". Toronto Star. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ Kalinowski, Tess (December 7, 2015). "Toll Lanes Coming to the QEW". Toronto Star. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ↑ "HOT Lanes, Derided as 'Lexus Lanes,' Inch Ahead in Ontario". CBC News. CBC/Radio Canada. December 7, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ↑ Campbell, Caitlin (April 4, 2012). "Sabres vs Leafs Historic Rivalry". The Hockey Writers. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

Bibliography

- Emery, Claire; Ford, Barbara (1967). From Pathway to Skyway. Confederation Centennial Committee of Burlington. pp. 179–182. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- Filey, Mike (1994). Toronto sketches 3: the way we were. Dundurn Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 1-55002-227-X. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- Shragge, John; Bagnato, Sharon (1984). From Footpaths to Freeways. Ontario Ministry of Transportation and Communications, Historical Committee. ISBN 0-7743-9388-2.

- Stamp, Robert M. (1987). QEW – Canada's First Superhighway. The Boston Mills Press. ISBN 0-919783-84-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Queen Elizabeth Way. |

- Live QEW Traffic Cameras through Hamilton, Halton Region and Peel Region

- Live QEW Traffic Cameras through St. Catharines and Niagara Falls

- Video of the Niagara-bound QEW from Highway 406 to 420

- Video of the QEW eastbound in Greater Toronto

- Queen Elizabeth Way at AsphaltPlanet.ca