Troglitazone

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (tablets) |

| ATC code | A10BG01 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Biological half-life | 16–34 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

97322-87-7 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5591 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 2693 |

| DrugBank |

DB00197 |

| ChemSpider |

5389 |

| UNII |

I66ZZ0ZN0E |

| KEGG |

D00395 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:9753 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL408 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

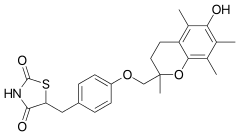

| Formula | C24H27NO5S |

| Molar mass | 441.541 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Melting point | 184 to 186 °C (363 to 367 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Troglitazone (Rezulin, Resulin, Romozin, Noscal) is an antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory drug, and a member of the drug class of the thiazolidinediones. It was prescribed for patients with diabetes mellitus type 2.[1] It was developed by Daiichi Sankyo (Japan). In the United States, it was introduced and manufactured by Parke-Davis in the late 1990s, but turned out to be associated with an idiosyncratic reaction leading to drug-induced hepatitis. The F.D.A. medical officer assigned to evaluate troglitazone, John Gueriguian, did not recommend its approval due to potential high liver toxicity; Parke-Davis complained to the FDA and Guerigian was subsequently removed from his post.[2] A full panel of experts approved it in January 1997.[3] Once the prevalence of adverse liver effects became known, troglitazone was withdrawn from the British market in December 1997, from the United States market in 2000, and from the Japanese market soon afterwards. It did not get approval in the rest of Europe.

Mechanism of action

Troglitazone, like the other thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone and rosiglitazone), works by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs).

Troglitazone is a ligand to both PPARα and – more strongly – PPARγ. Troglitazone also contains an α-tocopheroyl moiety, potentially giving it vitamin E-like activity in addition to its PPAR activation. It has been shown to reduce inflammation:[4] troglitazone use was associated with a decrease of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and a concomitant increase in its inhibitor (IκB). NFκB is an important cellular transcription regulator for the immune response.

History

Troglitazone was developed as the first anti-diabetic drug having a mechanism of action involving the enhancement of insulin sensitivity. At the time it was widely believed that such drugs, by addressing the primary metabolic defect associated with Type 2 diabetes, would have numerous benefits including avoiding the risk of hypoglycemia associated with insulin and earlier oral antidiabetic drugs. It was further believed that reducing insulin resistance would potentially reduce the very high rate of cardiovascular disease that is associated with diabetes.[5][6]

Parke-Davis/Warner Lambert submitted the diabetes drug Rezulin for U.S. Food and Drug Administration (F.D.A.) review on July 31, 1996. The medical officer assigned to the review, Dr. John L. Gueriguian, cited Rezulin's potential to harm the liver and the heart and he questioned its viability in lowering blood sugar for patients with adult-onset diabetes, recommending against the drug's approval. After complaints from the drugmaker, Gueriguian was removed on November 4, 1996 and his review was purged by the F.D.A.[7][8] Gueriguian and the company had a single meeting, at which Gueriguian used "intemperate" language; The company said it's objections were based on inappropriate remarks made by Gueriguian.[9] Parke-Davis said at the advisory committee that the risk of liver toxicity was comparable to placebo and that additional data of other studies confirmed this.[10] According to Peter Gøtzsche, when the company provided these additional data one week after approval, they showed a substantial greater risk for liver toxicity.[11]

The F.D.A. approved the drug on January 29, 1997, and it appeared in pharmacies in late March. At the time Dr. Solomon Sobel, a director at the F.D.A., overseeing diabetes drugs, said in a New York Times interview that adverse effects of troglitazone appeared to be rare and relatively mild.[12]

Glaxo Wellcome P.L.C. received approval from the British Medicines Control Agency (MCA) to market troglitazone, as Romozin, in July 1997.[13] After reports of sudden liver failure in patients receiving the drug, the Parke-Davis and the FDA added warnings to the drug label requiring monthly monitoring of liver enzyme levels.[14] Glaxo removed troglitazone from the market in Britain on December 1, 1997.[7] Glaxo had licensed the drug from Sankyo Company of Japan and had sold it in Britain from October 1, 1997.[15][16]

On May 17, 1998, a 55-year-old patient named Audrey LaRue Jones died of acute liver failure after taking troglitazone. Importantly, she had been monitored closely by physicians at the National Institutes of Health as a participant in the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) diabetes prevention study.[17][18] This called into question the efficacy of the monitoring strategy. The N.I.H. responded on June 4 by dropping troglitazone from the study.[8][19] Dr. David J. Graham, an F.D.A. epidemiologist charged with evaluating the drug, warned on March 26, 1999 of the dangers of using it and concluded that patient monitoring was not effective in protecting against liver failure. He estimated that the drug could be linked to over 430 liver failures and that patients incurred 1,200 times greater risk of liver failure when taking Rezulin.[8][20] Dr. Janet B. McGill, an endocrinologist who had assisted in the Warner–Lambert's early clinical testing of Rezulin, wrote in a March 1, 2000 letter to Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.): "I believe that the company . . . deliberately omitted reports of liver toxicity and misrepresented serious adverse events experienced by patients in their clinical studies."[21]

On March 21, 2000, the F.D.A. withdrew the drug from the market.[22] Dr. Robert I. Misbin, an F.D.A. medical officer, wrote in a July 3, 2000 letter to the House Energy and Commerce Committee of strong evidence that Rezulin could not be used safely, after having been threatened by the FDA with dismissal in March 2000.[7][23] By that time the drug had been linked to 63 liver-failure deaths and had generated sales of more than $2.1 billion for Warner-Lambert.[20] The drug cost $1,400 a year per patient in 1998.[16] Pfizer, which had acquired Warner-Lambert in February 2000, reported the withdrawal of Rezulin cost $136 million.[24]

Mechanisms of hepatotoxicity

Since the withdrawal in 2000, mechanisms of Troglitazone hepatotoxicity have been extensively studied using a variety of in vivo,[25] in vitro[26] and computational methods.[27] These studies have suggested that hepatotoxicity of Troglitazone results from a combination of two major factors i) Non-metabolic and ii) Metabolic.[28] The non-metabolic toxicity is a complex function of drug-protein interactions in the liver and biliary system. Initially the metabolic toxicity was largely associated with reactive metabolite formation from the thiazolidinedione and chromane rings of Troglitazone. Moreover, the formation of quinone and o-quinone methide reactive metabolites were proposed to be formed by metabolic oxidation of the OH group of the chromane ring.[25] Detailed quantum chemical analysis of the metabolic pathways for Troglitazone has shown that quinone reactive metabolite is generated by oxidation of the OH group, but o-quinone methide reactive metabolite is formed by the oxidation of the methyl (CH3) groups ortho to the OH group of the chromane ring.[27] This understanding has been recently used in the design of novel Troglitazone derivatives with anti-proliferative activity in breast cancer cell lines.[29]

Lawsuits

In 2009 Pfizer Inc. resolved all but three of 35,000 claims over its withdrawn diabetes drug Rezulin for a total of about $750 million. Pfizer, which acquired rival Wyeth for almost $64 billion, paid about $500 million to settle Rezulin cases consolidated in federal court in New York, according to court filings. The company also paid as much as $250 million to resolve state-court suits. In 2004, it set aside $955 million to end Rezulin cases.[30]

References

- ↑ Fisher, Lawrence (4 November 1997). "Adverse Diabetes Drug News Sends Warner-Lambert Down". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Retired Drugs: Failed Blockbusters, Homicidal Tampering, Fatal Oversights, wired.com

- ↑ Cohen, J. S. (2006). "Risks of troglitazone apparent before approval in USA". Diabetologia. 49 (6): 1454–5. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0245-0. PMID 16601971.

- ↑ Aljada A, Garg R, Ghanim H, et al. (2001). "Nuclear factor-kappaB suppressive and inhibitor-kappaB stimulatory effects of troglitazone in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: evidence of an antiinflammatory action?". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86 (7): 3250–6. doi:10.1210/jc.86.7.3250. PMID 11443197.

- ↑ Henry RR (September 1996). "Effects of troglitazone on insulin sensitivity". Diabet. Med. 13 (9 Suppl 6): S148–50. PMID 8894499.

- ↑ Keen H (November 1994). "Insulin resistance and the prevention of diabetes mellitus". N. Engl. J. Med. 331 (18): 1226–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199411033311812. PMID 7935664.

- 1 2 3 Willman, David (20 December 2000). "NEW FDA: Rezulin Fast-Track Approval and a Slow Withdrawal". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Willman, David (4 June 2000). "The Rise and Fall of the Killer Drug Rezulin". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ "Report: FDA Removes Medical Officer".

- ↑ Avorn, J (2005). Powerful medicines. New York: Vintage books.

- ↑ Gøtzsche, Peter (2013). Deadly medicines and organised crime : how big pharma has corrupted healthcare. London [u.a.]: Radcliffe Publ. p. 185. ISBN 9781846198847.

- ↑ Leary, Warren (31 January 1997). "New Class of Diabetes Drug Is Approved". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Sinclair, Neil (31 July 1997). "Glaxo Wellcome gets approval for Romozin". ICIS News. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ "www.accessdata.fda.gov" (PDF).

- ↑ British Broadcasting Corporation (1 December 1997). "Diabetes drug withdrawn from sale". BBC. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- 1 2 Fisher, Lawrence (17 January 1998). "Drug Makers at Threshold of a New Therapy; With a Dose of Biotechnology, Big Change Is Ahead in the Treatment of Diabetes". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Diabetes Prevention Research Group (April 1999). "Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetes" (PDF). Diabetes Care. 22 (4): 623–634. doi:10.2337/diacare.22.4.623. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (7 February 2002). "Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin". The New England Journal of Medicine. 346 (6): 393–403. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa012512. PMC 1370926

. PMID 11832527. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

. PMID 11832527. Retrieved 12 December 2012. - ↑ Gale, Edwin (January 2006). "Troglitazone: the lesson that nobody learned?". Diabetologia. 49 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1007/s00125-005-0074-6.

- 1 2 Willman, David (16 August 2000). "FDA's Approval and Delay in Withdrawing Rezulin Probed". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Willman, David (10 March 2000). "Fears Grow Over Delay in Removing Rezulin". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "2000 Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Willman, David (March 17, 2000). "Physician Who Opposes Rezulin Is Threatened by FDA With Dismissal". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Pfizer. "Pfizer Annual Report 2001" (PDF). Pfizer. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- 1 2 Kassahun, Kelem; Pearson, Paul G.; Tang, Wei; McIntosh, Ian; Leung, Kwan; Elmore, Charles; Dean, Dennis; Wang, Regina; Doss, George (2001-01-01). "Studies on the Metabolism of Troglitazone to Reactive Intermediates in Vitro and in Vivo. Evidence for Novel Biotransformation Pathways Involving Quinone Methide Formation and Thiazolidinedione Ring Scission†". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 14 (1): 62–70. doi:10.1021/tx000180q. ISSN 0893-228X.

- ↑ Funk, Christoph; Ponelle, Christiane; Scheuermann, Gerd; Pantze, Michael (2001-03-01). "Cholestatic Potential of Troglitazone as a Possible Factor Contributing to Troglitazone-Induced Hepatotoxicity: In Vivo and in Vitro Interaction at the Canalicular Bile Salt Export Pump (Bsep) in the Rat". Molecular Pharmacology. 59 (3): 627–635. doi:10.1124/mol.59.3.627. ISSN 1521-0111. PMID 11179459.

- 1 2 Dixit, Vaibhav A.; Bharatam, Prasad V. (2011-07-18). "Toxic Metabolite Formation from Troglitazone (TGZ): New Insights from a DFT Study". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 24 (7): 1113–1122. doi:10.1021/tx200110h. ISSN 0893-228X.

- ↑ Masubuchi, Yasuhiro (2006-10-01). "Metabolic and non-metabolic factors determining troglitazone hepatotoxicity: a review". Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 21 (5): 347–356. ISSN 1347-4367. PMID 17072088.

- ↑ Salamone, Stéphane; Colin, Christelle; Grillier-Vuissoz, Isabelle; Kuntz, Sandra; Mazerbourg, Sabine; Flament, Stéphane; Martin, Hélène; Richert, Lysiane; Chapleur, Yves (2012-05-01). "Synthesis of new troglitazone derivatives: Anti-proliferative activity in breast cancer cell lines and preliminary toxicological study". European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 51: 206–215. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.02.044.

- ↑ Feeley, Jef (March 31, 2009). "Pfizer Ends Rezulin Cases With $205 Million to Spare". Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

External links

- Diabetes Monitor article on troglitazone

- RxList article on troglitazone