Rhine Campaign of 1796

| Rhine Campaign of 1796 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of War of the First Coalition | |||||||

French advance guard overwhelming Swabians at Kehl | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Army of Sambre-et-Meuse Army of Rhin-et-Moselle |

Army of the Lower Rhine Army of the Upper Rhine | ||||||

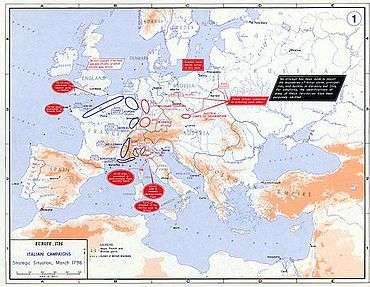

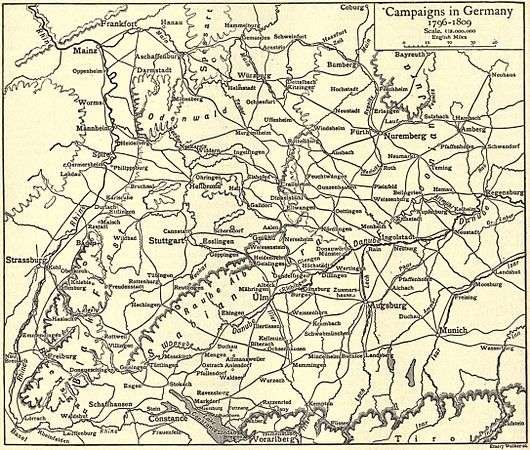

The Rhine Campaign of 1796 (June 1796 to January 1797) saw two Habsburg Austrian armies under the overall command of Archduke Charles brilliantly outmaneuver and defeat an attempt by two Republican French armies to conquer southern Germany. At the start of the campaign the French Army of Sambre-et-Meuse under Jean Baptiste Jourdan faced the Austrian Army of the Lower Rhine in the north, while the French Army of Rhin-et-Moselle led by Jean Victor Marie Moreau confronted the Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine in the south. After sending large reinforcements to Italy in May, Austria was forced onto the defensive. After Jourdan lured Charles to the north, Moreau forced a crossing of the Rhine at Kehl on 24 June and beat the archduke's southern Austrian army at the battles of Ettlingen on 9 July and Neresheim on 11 August. Both French armies penetrated deeply into southern Germany in August.

Because the two French armies operated independently, Archduke Charles was able to leave Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour with a weaker army in front of Moreau and move heavy reinforcements to help Wilhelm von Wartensleben's army in the north. In battles at Amberg on 24 August and Würzburg on 3 September Charles defeated Jourdan and compelled his army to retreat to the west bank of the Rhine. With Jourdan neutralized, Charles left Franz von Werneck to keep an eye on the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse and turned on Moreau who belatedly began to withdraw from southern Germany. Moreau briskly repulsed Latour at Biberach and safely reached the Rhine before Charles cut him off from France. However, in the battles of Emmendingen and Schliengen in October, Charles forced Moreau to retreat to the west bank of the Rhine. During the winter the Austrians reduced the French bridgeheads at Kehl and Huningue (Hüningen). Despite Charles' splendid success in Germany, Austria was losing the war in Italy to a new French army commander named Napoleon Bonaparte.

Plans

In a decree on 6 January 1796, Lazare Carnot gave Germany priority over Italy as a theater of war. Jean Baptiste Jourdan commanding the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse was instructed to besiege Mainz and cross the Rhine into Franconia. Farther south, Jean Victor Marie Moreau leading the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle was ordered to mask Mannheim and invade Swabia. On the secondary front, Napoleon Bonaparte was to invade Italy, neutralize the Kingdom of Sardinia and seize Lombardy from the Austrians. Hopefully, the Italian army would cross the Alps via the County of Tyrol and join the other French armies in crushing the Austrian forces in southern Germany. By the spring of 1796, Jourdan and Moreau each had 70,000 men while Bonaparte's army numbered 63,000, including reserves and garrisons. Additionally, François Christophe de Kellermann counted 20,000 troops in the Army of the Alps and there was an even smaller army in southern France. The First French Republic's finances were in poor shape so its armies were expected to invade new territories and then live off the conquered lands.[1]

At the end of the Rhine Campaign of 1795 the two sides called a truce.[2] This accord lasted until 20 May 1796 when the Austrians announced that it would end on 31 May.[3] The Army of the Lower Rhine was commanded by the 25-year-old Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen and counted 90,000 troops. The 20,000-man right wing under Duke Ferdinand Frederick Augustus of Württemberg was on the east bank of the Rhine behind the Sieg River observing the French bridgehead at Düsseldorf. The garrisons of Mainz Fortress and Ehrenbreitstein Fortress counted 10,000 more. The remainder of Charles' army was posted on the west bank behind the Nahe River. Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser led the 80,000-strong Army of the Upper Rhine. Its right wing occupied Kaiserslautern on the west bank while the left wing under Anton Sztáray, Michael von Fröhlich and Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé guarded the Rhine from Mannheim to Switzerland.[2]

The original Austrian strategy was to capture Trier and to use their position on the west bank to strike at each of the French armies in turn. However, Wurmser was sent to Italy with 25,000 reinforcements after news arrived of Bonaparte's early successes. In the new situation, the Aulic Council gave Archduke Charles command over both Austrian armies and ordered him to hold his ground.[2]

At the start of the campaign, the 80,000-man Army of Sambre-et-Meuse held the west bank of the Rhine down to the Nahe and then southwest to Sankt Wendel. On the army's left flank, Jean Baptiste Kléber had 22,000 troops in an entrenched camp at Düsseldorf. Carnot's grand plan called for the two French armies to press against the Austrian flanks. But first, Jourdan's army would push south from Düsseldorf. It was hoped that this advance would induce the Austrians to withdraw all of their forces from the Rhine's west bank. It would also focus Austrian attention northward, allowing Moreau's army to more easily strike in the south. The right wing of the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle was positioned behind the Rhine from Huningue (Hüningen) northward, its center was along the Queich River near Landau and its left wing extended west toward Saarbrücken.[2]

Pierre Marie Barthélemy Ferino led Moreau's Right Wing, Louis Desaix commanded the Center and Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr directed the Left Wing. Ferino's wing consisted of three divisions under François Antoine Louis Bourcier, 9,281 infantry and 690 cavalry, Henri François Delaborde, 8,300 infantry and 174 cavalry and Augustin Tuncq, 7,437 infantry and 432 cavalry. Desaix's command counted three divisions led by Michel de Beaupuy, 14,565 infantry and 1,266 cavalry, Antoine Guillaume Delmas, 7,898 infantry and 865 cavalry and Charles Antoine Xaintrailles, 4,828 infantry and 962 cavalry. Saint-Cyr's wing had two divisions commanded by Guillaume Philibert Duhesme, 7,438 infantry and 895 cavalry and Alexandre Camille Taponier, 11,823 infantry and 1,231 cavalry. Altogether, Moreau's Army of Rhin-et-Moselle numbered 71,581 foot soldiers and 6,515 cavalry. Gunners and sappers are not included in the total.[4]

Terrain

Geography

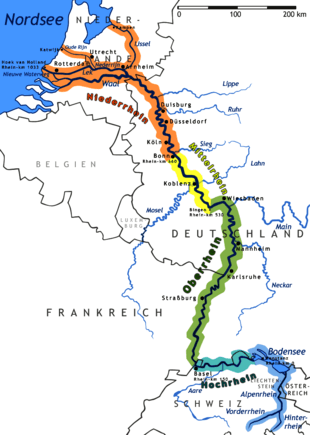

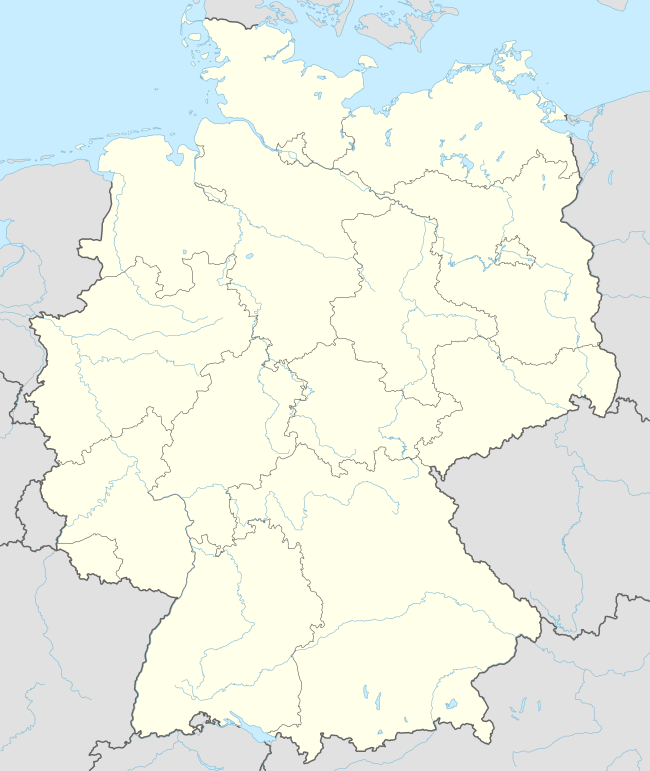

The Rhine River flows west along the border between the German states and the Swiss Cantons.[Note 1] The 80-mile (130 km) stretch between Rheinfall, by Schaffhausen and Basel, the High Rhine cuts through steep hillsides over a gravel bed; in such places as the former rapids at Laufenburg, it moved in torrents.[5] A few miles north and east of Basel, the terrain flattens. The Rhine makes a wide, northerly turn, in what is called the Rhine knee, and enters the so-called Rhine ditch (Rheingraben), part of a rift valley bordered by the Black Forest on the east and Vosges Mountains on the west. In 1796, the plain on both sides of the river, some 19 miles (31 km) wide, was dotted with villages and farms. At both far edges of the flood plain, especially on the eastern side, the old mountains created dark shadows on the horizon. Tributaries cut through the hilly terrain of the Black Forest, creating deep defiles in the mountains. The tributaries then wind in rivulets through the flood plain to the river.[6]

The Rhine River itself looked different in the 1790s than it does in the twenty-first century; the passage from Basel to Iffezheim was "corrected" (straightened) between 1817 and 1875. Between 1927 and 1975, a canal was constructed to control the water level. In the 1790s, the river was wild and unpredictable, in some places four or more times wider than the twenty-first century incarnation of the river, even under regular conditions. Its channels wound through marsh and meadow, and created islands of trees and vegetation that were periodically submerged by floods.[7] It was crossable at Kehl, by Strasbourg, and Hüningen, by Basel, where systems of viaducts and causeways made access reliable.[8]

Political terrain

| Complications of political boundaries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

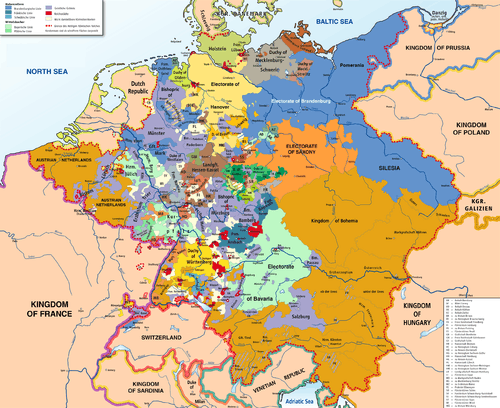

The German-speaking states on the east bank of the Rhine were part of the vast complex of territories in central Europe called the Holy Roman Empire.[9] The considerable number of territories in the Empire included more than 1,000 entities. Their size and influence varied, from the Kleinstaaterei, the little states that covered no more than a few square miles, or included several non-contiguous pieces, to the small and complex territories of the princely Hohenlohe family branches, to such sizable, well-defined territories as the Kingdoms of Bavaria and Prussia. The governance of these many states varied: they included the autonomous free imperial cities, also of different sizes and influence, from the powerful Augsburg to the minuscule Weil der Stadt; ecclesiastical territories, also of varying sizes and influence, such as the wealthy Abbey of Reichenau and the powerful Archbishopric of Cologne; and dynastic states such as Württemberg. When viewed on a map, the Empire resembled a "patchwork carpet". Both the Habsburg domains and Hohenzollern Prussia also included territories outside the Empire. There were also territories completely surrounded by France that belonged to Württemberg, the Archbishopric of Trier, and Hesse-Darmstadt. Among the German-speaking states, the Holy Roman Empire's administrative and legal mechanisms provided a venue to resolve disputes between peasants and landlords, between jurisdictions, and within jurisdictions. Through the organization of imperial circles, also called Reichskreise, groups of states consolidated resources and promoted regional and organizational interests, including economic cooperation and military protection.[10]

Operations

Crossing the Rhine

According to plan, Kléber made the first move, advancing south from Düsseldorf against Württemberg's wing of the Army of the Lower Rhine.[2] On 1 June 1796, a division of Kléber's troops led by François Joseph Lefebvre seized a bridge over the Sieg from Michael von Kienmayer's Austrians at Siegburg. Meanwhile, a second French division under Claude-Sylvestre Colaud menaced the Austrian left flank.[11] Württemberg retreated south to Uckerath but then fell back farther to a well-fortified position at Altenkirchen. On 4 June, Kléber defeated Württemberg in the Battle of Altenkirchen, capturing 1,500 Austrian soldiers, 12 artillery pieces and four colors. Archduke Charles withdrew the Austrian forces from the Rhine's west bank and gave the Army of the Upper Rhine responsibility to defend Mainz.[12] After this setback, Charles replaced Württemberg with Wilhelm von Wartensleben. Afterward the duke became a harsh critic of the archduke.[13] Jourdan's main body crossed the Rhine on 10 June at Neuwied to join Kléber[2] and the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse advanced to the Lahn River. In the south Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour took command of the Army of the Upper Rhine in place of Wurmser.[14]

Leaving 12,000 troops to guard Mannheim, Charles reapportioned his remaining troops among his two armies. Then he swiftly moved north against Jourdan. The archduke defeated the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse at the Battle of Wetzlar on 15 June 1796 and Jourdan lost no time in recrossing the Rhine at Neuwied.[14] Following up, the Austrians clashed with Kléber's divisions at Uckerath, inflicting 3,000 casualties on the French for a loss of only 600. After his success, Charles left 35,000 men with Wartensleben, 30,000 more in Mainz and other fortresses and moved south with 20,000 troops to help Latour. Kléber withdrew within the Düsseldorf defenses.[15]

Also on 15 June, Desaix's 30,000-man command mauled Franz Petrasch's 11,000 Austrians at Maudach. The French lost 600 casualties while the Austrians suffered three times as many.[16] After feinting at the Austrian positions near Mannheim, Moreau sent his army south from Speyer on a forced march toward Strasbourgh; Desaix across the Rhine at Kehl near Strasbourg on the night of 23–24 June.[14] In the First Battle of Kehl the 10,065 French troops involved in the initial assault crossing lost only 150 casualties. The defending forces, 7,000 men from the Swabian Circle, put up a sturdy defense before withdrawing. The Swabians lost 700 casualties, 14 guns and 22 ammunition wagons.[16] Moreau reinforced his newly-won bridgehead on 26 and 27 June so that he had 30,000 troops to oppose only 18,000 locally based Austrians. Leaving Delaborde's division on the west bank to watch the Rhine between Neuf-Brisach and Huningue, Moreau moved to the north against Latour. Separated from their chief, the Austrian left flank troops under Fröhlich and the Prince Condé withdrew to the southeast.[14] At Renchen on 28 June, Desaix caught up with Sztáray's column of 9,000 Austrian and Reichsarmee (Imperial) troops. For only 200 of their own casualties, the French inflicted losses of 550 killed and wounded, while capturing 850 men, seven guns and two ammunition wagons. Henceforth, the Imperial troops (Kreistruppen) took little part in the campaign and they were disarmed by Fröhlich on 29 July at Biberach an der Riss.[17]

Ferino pursued Fröhlich and the Prince Condé in the direction of Villingen while Saint-Cyr chased after the Kreistruppen. Latour and Sztáray tried to hold the line of the Murg River.[18] On 5 July 1796, Desaix defeated Latour at the Battle of Rastatt and drove him back to the Alb River.[18] The French employed 19,000 foot soldiers and 1,500 horsemen in the divisions of Taponier and Bourcier. The Austrian brought 6,000 men into action under the command of Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg and Johann Mészáros von Szoboszló. The French captured 200 Austrians and three field pieces.[19] By this time Archduke Charles had arrived with reinforcements. Charles prepared to advance against Moreau on 10 July but the Frenchman surprised him by attacking first. In the Battle of Ettlingen on 9 July, Charles repulsed Desaix's attacks on his right flank, but Saint-Cyr and Taponier gained ground in the hills to the east. Anxious for his supply lines, Charles began a retreat to the east.[18] At Ettlingen, Moreau lost 2,400 out of 36,000 men while Charles had 2,600 hors de combat out of 32,000 troops.[20]

French offensive

With Charles absent from the north, Jourdan crossed the Rhine for the second time and drove Wartensleben behind the Lahn. Pushing forward again, Army of Sambre-et-Meuse defeated its opponents in the Battle of Friedberg-Hesse.[21] In the 10 July action, the Austrians suffered 1,000 casualties against a French loss of 700.[20] Jourdan captured Frankfurt am Main on the 16th. Leaving behind François Séverin Marceau-Desgraviers with 28,000 troops to blockade Mainz and Ehrenbreitstein, Jourdan pressed up the Main River. Following Carnot's strategy, the French commander continually operated against Wartensleben's north flank, causing the Austrian general to fall back.[21] At about this time Jourdan's army numbered 46,197 men while Wartensleben counted 36,284 troops.[22] Buoyed up by their forward movement and by the capture of Austrian supplies, the French captured Würzburg on 4 August. The Army of Sambre-et-Meuse under the temporary direction of Kléber won a clash with Wartensleben at Forchheim on 7 August. [21]

Meanwhile, in the south the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle clashed with Charles' retreating army at Cannstadt near Stuttgart on 21 July 1796.[20] The Swabians and Electorate of Bavaria began to negotiate with Moreau for an exit from the war. Charles retreated through Geislingen an der Steige around 2 August and was in Nördlingen by 10 August. At this date, Moreau had 45,000 men spread out on a 25 miles (40 km) front centered on Neresheim with both flanks in the air. Meanwhile, Ferino's right wing was out of touch far to the south at Memmingen. Charles desired to cross to the south bank of the Danube River, but Moreau was close enough to interfere with the operation. So, the archduke determined to launch an attack. The Battle of Neresheim on 11 August was a series of clashes fought on a broad front. The Austrians drove back Moreau's right flank and nearly captured his artillery park, putting the French in an awkward position. When Moreau got ready to fight the following day he found that the Austrians had slipped away and were crossing the Danube. Both armies lost about 3,000 men.[23]

At this point in the campaign Moreau passed up an opportunity to move north and unite with Jourdan's army. Theodore Ayrault Dodge asserted that the combined army "could have crushed the Austrians".[23] Napoleon later wrote of Moreau's actions, "One would have said that he was ignorant that a French army existed on his left".[21] In the north there was a battle at Sulzbach on 17 August in which Paul Kray's Austrians inflicted losses of 1,000 killed and wounded and 700 captured on their enemies while suffering losses of 900 killed and wounded and 200 captured. However, this clash did not halt the French advance.[24] Wartensleben's army retreated behind the Naab River on 18 August. As Jourdan closed up to the Naab[21] he posted Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte's division at Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz to observe Charles.[25] South of the Danube, Charles received reinforcements that brought his strength up to 60,000 troops. He left 35,000 soldiers under the command of Latour to contain the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle.[23] With 25,000 of his best troops, the archduke crossed to the north bank of the Danube at Regensburg and moved north to join his colleague Wartensleben.[25]

Austrian counteroffensive

On 22 August 1796, Archduke Charles and Friedrich Joseph, Count of Nauendorf encountered Bernadotte's division at Neumarkt.[24] The outnumbered French were driven northwest through Altdorf bei Nürnberg to the Pegnitz River. Leaving Friedrich Freiherr von Hotze with a division to follow Bernadotte, the archduke thrust north at Jourdan's right flank. The French general fell back to Amberg as Charles and Wartensleben's forces converged on the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse. In the Battle of Amberg on 24 August, Charles defeated the French and destroyed two battalions of their rear guard.[25] The Austrians lost 400 killed and wounded out of 40,000 troops. Of a total of 34,000 soldiers, the French suffered losses of 1,200 killed and wounded plus 800 men and two colors captured.[26] Jourdan retreated first to Sulzbach and then behind the Wiesent River where he was joined by Bernadotte on 28 August. Meanwhile, Hotze reoccupied Nürnberg. Jourdan had expected Moreau to keep Charles occupied in the south but now found himself facing a numerically superior enemy.[25]

Moreau crossed to the south bank of the Danube on 19 August, leaving only Delmas' division on the north bank.[27] By no later than the 20th Moreau was aware that the archduke had recrossed the Danube, heading north, but instead the French general pressed eastward toward the Lech River. On that day Moreau sent Jourdan a misleading message vowing to closely follow Charles.[28] Ferino's wandering right wing finally rejoined the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle on 22 August, though Delaborde's division remained well to the south. Its only notable action was repulsing a night attack by the 5,000 to 6,000-man Army of Condé at Kammlach on 13-14 August. The French Royalists and their mercenaries sustained 720 casualties while Ferino lost a number of prisoners. In this action Captain Maximilien Sébastien Foy led a Republican horse artillery battery with distinction.[29] The combative Latour rashly stood to fight on the Lech near Augsburg on 24 August. Despite rising waters in which some soldiers drowned, Saint-Cyr and Ferino attacked across the river.[30] In the Battle of Friedberg the French crushed an Austrian infantry regiment, inflicting losses of 600 killed and wounded plus 1,200 men and 17 field guns captured. French casualties numbered 400.[26]

As Jourdan fell back to Schweinfurt he saw a chance to retrieve his campaign by offering battle at Würzburg in the bend of the Main River.[31] At this time Jourdan had a spat with his wing commander Kléber and that officer suddenly resigned his command. Two generals from Kléber's clique, Bernadotte and Colaud made excuses to immediately leave the army. Faced with this minor mutiny, Jourdan replaced Bernadotte with Henri Simon and split up Colaud's units among the other divisions.[32] Undeterred, Jourdan marched south with 30,000 men in the infantry divisions of Simon, Jean Étienne Championnet and Paul Grenier and Jacques Philippe Bonnaud's reserve cavalry. Lefebvre's division, 10,000-strong was left at Schweinfurt in case of retreat. Anticipating Jourdan's move, Charles rushed his army toward battle, Johann I Joseph, Prince of Liechtenstein seizing Würzburg on 1 September.[31] Marshalling the divisions of Hotze, Sztáray, Kray, Johann Sigismund Riesch and Wartensleben, the Austrians won the Battle of Würzburg on 3 September, forcing the French to retreat to the Lahn. Charles lost 1,500 casualties out of 44,000 troops while inflicting 2,000 casualties on the outnumbered French.[33] Another authority gave French losses as 2,000 killed and wounded plus 1,000 men and seven guns captured, while Austrian losses numbered 1,200 killed and wounded and 300 captured. The French were compelled to lift the siege of Mainz on 7 September.[34]

On 10 September, Marceau rejoined the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse with 12,000 troops from the blockade of the east side of Mainz. Jean Hardy's division on the west side of Mainz retreated to the Nahe. At this moment, the French government belatedly transferred two divisions from the idle Army of the North, those of Jacques MacDonald and Jean Castelbert de Castelverd. Of these, MacDonald's stopped at Düsseldorf while Castelverd's was placed in line on the lower Lahn. These reinforcements brought Jourdan's strength up to 50,000. Jourdan, who had already resigned his command, hoped to be able to maintain his army along the Lahn. By relieving the fortresses on the Rhine, Charles made 16,200 troops available from Mainz and released 11,630 from Mannheim and Philippsburg.[35]

On 16 September Charles defeated the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse in the Battle of Limburg.[36] Kray assaulted Grenier's troops on the French left wing at Giessen but was repulsed. In the struggle, Bonnaud was badly wounded and died six months later. Meanwhile, Charles made his main effort against André Poncet's division of Marceau's right wing at Limburg an der Lahn. After an all-day combat, Poncet's lines still held except for a small bridgehead at nearby Diez. Though not threatened, that night Castelverd panicked and withdrew his division without orders from Marceau. With a gaping hole on their right, Marceau and Bernadotte (now returned to his division) made a fighting withdrawal to Altenkirchen, allowing the left wing to escape. Marceau was fatally wounded on the 19th and died the next morning.[37] Over the next few days, Jourdan's army withdrew to the west bank of the Rhine. Castelverd held east bank entrenchments at Neuwied, Poncet crossed at Bonn while the other divisions retired behind the Sieg. Jourdan handed over command to Pierre de Ruel, marquis de Beurnonville on the 22nd. Charles now left 32,000 to 36,000 troops in the north, 9,000 more in Mainz and Mannheim and moved south with 16,000 to help intercept Moreau.[38] Franz von Werneck was placed in charge of the northern force.[39] Though Beurnonville's army grew to 80,000 men, he remained completely passive in the fall and winter of 1796.[40] The disgraced Castelverd was later replaced by Jacques Desjardin.[41]

Moreau's retreat

While the French strategy was being ruined in the north, Moreau moved too slowly in Bavaria. On 3 September Saint-Cyr captured a crossing of the Isar River at Freising while Latour regrouped at Landshut. Moreau sent Desaix to the Danube's north bank on 10 September, but Charles ignored this threat. It soon became obvious that the Army of Rhin-et-Meuse was isolated and must retreat.[42] On 18 September, Petrasch and 5,000 Austrians briefly captured the fortified bridgehead at Kehl before being driven out by Balthazar Alexis Henri Schauenburg's counterattack. Each side suffered 2,000 killed, wounded and captured.[43] Instead of burning the bridge, Petrasch's men had plundered the French camp. In Bavaria, Moreau with 64,000 troops was hounded by Latour's 16,960 men to the east, Fröhlich's 10,906 soldiers to the south, Nauendorf's 5,815 men to the north and Petrasch's 5,564 troops to the west.[44] Moreau began retreating on 19 September.[45] By the 21st the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle reached the Iller River.[46]

Latour had ambitions of destroying Moreau's army and pressed the French hard. On 1 October, the Austrians attacked but were repulsed by a brigade under Claude Lecourbe. On 2 October, Moreau with 39,000 troops defeated Latour's 24,000 men in the Battle of Biberach.[47] That morning Latour's army was deployed in a bad position with the Riss River behind it. Moreau ordered Desaix's left wing to attack Latour's right under Siegfried von Kospoth. Saint-Cyr's center was directed to assault Latour's center while Ferino turned the Austrian left under Condé and Karl Mercandin. Ferino was too distant to intervene, but his colleagues drove back the Austrians and seized Biberach an der Riss together with 4,000 Austrian prisoners, 18 guns and two colors.[48] The French lost 500 killed and wounded while the Austrians lost 300.[43]

Moreau preferred to retreat through the Black Forest by the Kinzig River valley but Nauendorf blocked that route. Instead, Saint-Cyr's column led the way over the Höllenthal, breaking through the Austrian net at Neustadt and reaching Freiburg im Breisgau on 12 October. Moreau's trains took a route down the Wiese River to Hunigue. The French general wanted to reach Kehl farther down the Rhine, but by this time Charles barred the way with 35,000 soldiers. In order for his trains to get away, Moreau needed to hold his position for a few days.[49] The Battle of Emmendingen was fought on 19 October, the 32,000 French losing 1,000 killed and wounded plus 1,800 men and two guns captured. The Austrians sustained 1,000 casualties out of 28,000 troops engaged. Beaupuy and Wartensleben were both killed.[43] There was some fighting on the 20th but when Charles advanced on 21 October the French were gone.[49]

Moreau sent Desaix's wing to the west bank of the Rhine at Breisach and offered battle at Schliengen. Saint-Cyr held the low ground on the left near the Rhine while Ferino defended the hills on the right. Charles hoped to turn the French right and trap Moreau's army against the Rhine.[50] In the Battle of Schliengen on 24 October, the French suffered 1,200 casualties out of 32,000 engaged. The Austrians counted 800 casualties out of 36,000 men.[51] The French held off the Austrian attacks but retreated the next day and recrossed to the west bank of the Rhine on 26 October.[50] There remained the two east bank French bridgeheads. Moreau ordered Desaix to defend Kehl while Ferino and Abbatucci were to hold Hunigue.[52]

Moreau offered Charles an armistice and the archduke was eager to accept it so that he could send 10,000 reinforcements to Italy. However, the Austrian government directed him to refuse it and reduce Kehl and Huningue. Accordingly, Charles gave Latour 29,000 infantry and 5,900 cavalry and ordered him to capture Kehl.[53] The Siege of Kehl lasted from 10 November to 9 January 1797 during which the French suffered 4,000 and the Austrians 4,800 casualties.[54] By a negotiated agreement, the French surrendered Kehl in return for an undisturbed withdrawal of the garrison into Strasbourg. After the Siege of Hüningen, the east-bank bridgehead of Huningue was handed over in a similar agreement on 5 February.[55] That siege had started on 27 November 1796 and had been conducted by Fürstenberg.[56] In January, the French began transferring two divisions to Bonaparte's army in Italy. These were Bernadotte's 12,000 from the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse and Delmas's 9,500 from the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle.[57]

Commentary

Historian Dodge called Archduke Charles' military operations "masterful" but noted the huge difference in results between the Rhine and Italian campaigns. "In Germany, each opponent ended where he began; Bonaparte won all northern Italy by his new method of conducting war." Dodge credited Moreau with "ordinary talent" and Jourdan with even less. He stated that Carnot's plan of allowing his two armies to operate on separated lines contained the "element of failure".[58]

Ramsay Weston Phipps wondered why Moreau gained renown by the supposed skill of his retreat. Phipps suggested that it was not skillful for Moreau to allow the inferior columns of Latour, Nauendorf and Fröhlich to herd him back to France. Even during his advance Moreau was irresolute.[59] Jean-de-Dieu Soult, who participated in the campaign as an infantry brigadier, noted that Jourdan made many errors but the French government's errors were worse. The French were unable to pay for supplies because the money was worthless, so the soldiers stole everything. This ruined discipline and turned the local populations against the French.[60] Jourdan seemed to have an unwarranted faith in Moreau's promise to follow Charles. His fatal decision to give battle at Würzburg was partly done so as not to leave Moreau in the lurch.[61]

Notes

- ↑ These territories include present-day Baden-Württemberg and the Cantons of Schaffhausen, Aargau, Basel-land, and Basel-Stadt. Schaffhausen and Aargau attained canton status in the peace settlement of 1803, a de facto acceptance of the Swiss Revolution of 1798-99; Basel-land and Basel-Stadt were created from the Canton Basel in 1833.

Citations

- ↑ Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan. pp. 46–47.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (2011). Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: The Revolutionary Wars Against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789-1797. USA: Leonaur Ltd. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-0-85706-598-8.

- ↑ Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011). The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.

- ↑ Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. p. 111. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- ↑ Laufenburg now has dams and barrages to control the flow of water. Thomas P. Knepper. The Rhine. Handbook for Environmental Chemistry Series, Part L. New York: Springer, 2006, ISBN 978-3-540-29393-4, pp. 5–19.

- ↑ Knepper, pp. 19–20

- ↑ (German) Helmut Volk. "Landschaftsgeschichte und Natürlichkeit der Baumarten in der Rheinaue." Waldschutzgebiete Baden-Württemberg, Band 10, pp. 159–167.

- ↑ Thomas C Hansard (ed.).Hansard's Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 1803, Official Report. Vol. 1. London: HMSO, 1803, pp. 249–252.

- ↑ Whaley, Joachim (2012). "Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648". Oxford University Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 0199688826.

- ↑ See, for example, Vann, James Allen (1975). The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715. 52. Brussels: Studies Presented to International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions. and Walker, Mack (1998). German home towns: community, state, and general estate, 1648–1871. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. OCLC 2276157.

- ↑ Rickard, J. (2009). "Combat of Siegburg, 1 June 1796". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ Rickard, J. (2009). "First battle of Altenkirchen, 4 June 1796". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Digby; Kudrna, Leopold. "Austrian Generals of 1792-1815: Württemberg, Ferdinand Friedrich August Herzog von". napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Dodge (2011), p. 288

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 115

- 1 2 Smith (1998), p. 114

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 115-116

- 1 2 3 Dodge (2011), p. 290

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 116

- 1 2 3 Smith (1998), p. 117

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dodge (2011), p. 296

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 302

- 1 2 3 Dodge (2011), pp. 292-293

- 1 2 Smith (1998), p. 120

- 1 2 3 4 Dodge (2011), p. 297

- 1 2 Smith (1998), pp. 120-121

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 326

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 328-329

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 330-332

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 334-335

- 1 2 Dodge (2011), p. 298

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 348-349

- ↑ Dodge (2011), p. 301

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 122

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 353-354

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 124

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 360-364

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 366

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 420

- ↑ Dodge (2011), p. 344

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 389

- ↑ Dodge (2011), pp. 302-303

- 1 2 3 Smith (1998), p. 125

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 367

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 369

- ↑ Dodge (2011), p. 304

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 371

- ↑ Dodge (2011), pp. 304-306

- 1 2 Dodge (2011), pp. 306-308

- 1 2 Dodge (2011), pp. 308-310

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 126

- ↑ Dodge (2011), p. 311

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 382

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 131

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 393-394

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 132

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 405-406

- ↑ Dodge (2011), pp. 311-313

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 400-402

- ↑ Phipps (2011), pp. 395-396

- ↑ Phipps (2011), p. 347

References

- Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan.

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (2011). Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: The Revolutionary Wars Against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789-1797. USA: Leonaur Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85706-598-8.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011). The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Combat of Siegburg, 1 June 1796". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Rickard, J. (2009). "First battle of Altenkirchen, 4 June 1796". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Smith, Digby; Kudrna, Leopold. "Austrian Generals of 1792-1815: Württemberg, Ferdinand Friedrich August Herzog von". napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Vann, James Allen (1975). The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715. 52. Brussels: Studies Presented to International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions.

- Walker, Mack (1998). German home towns: community, state, and general estate, 1648–1871. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. OCLC 2276157.

- Whaley, Joachim (2012). "Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648". Oxford University Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 0199688826.