Rùm

| Gaelic name |

|

|---|---|

| Norse name | possibly rõm-øy |

| Meaning of name | unclear |

| Location | |

Rùm Rùm shown within Lochaber | |

| OS grid reference | NM360976 |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Small Isles |

| Area | 10,463 hectares (40.4 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 15 [1] |

| Highest elevation | Askival 812 metres (2,664 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Highland |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 22[2] |

| Population rank | 64 [1] |

| Pop. density | 0.2 people/km2[2][3] |

| Largest settlement | Kinloch |

| References | [3][4] |

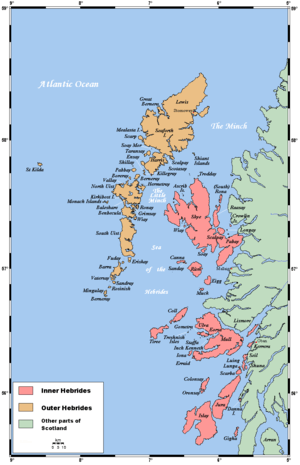

Rùm (Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [rˠuːm]), a Scottish Gaelic name often anglicised to Rum, is one of the Small Isles of the Inner Hebrides, in the district of Lochaber, Scotland. For much of the 20th century the name became Rhum, a spelling invented by the former owner, Sir George Bullough, because he did not relish the idea of having the title "Laird of Rum".

It is the largest of the Small Isles, and the 15th largest Scottish island, but is inhabited by only about thirty or so people, all of whom live in the village of Kinloch on the east coast. The island has been inhabited since the 8th millennium BC and provides some of the earliest known evidence of human occupation in Scotland. The early Celtic and Norse settlers left only a few written accounts and artefacts. From the 12th to 13th centuries on, the island was held by various clans including the MacLeans of Coll. The population grew to over 400 by the late 18th century but was cleared of its indigenous population between 1826 and 1828. The island then became a sporting estate, the exotic Kinloch Castle being constructed by the Bulloughs in 1900. Rùm was purchased by the Nature Conservancy Council in 1957.

Rùm is mainly igneous in origin, and its mountains have been eroded by Pleistocene glaciation. It is now an important study site for research in ecology, especially of red deer, and is the site of a successful reintroduction programme for the white-tailed sea eagle. Its economy is entirely dependent on Scottish Natural Heritage, a public body that now manages the island, and there have been calls for a greater diversity of housing provision. A Caledonian MacBrayne ferry links the island with the mainland town of Mallaig.

Etymology and placenames

Haswell-Smith (2004) suggests that Rum is "probably" pre-Celtic, but may be Old Norse rõm-øy for "wide island" or Gaelic ì-dhruim (pronounced [iˈɣɾɯim]) meaning "isle of the ridge". Ross (2007) notes that there is a written record of Ruim from 677 and suggests "spacious island" from the Gaelic rùm. Mac an Tàilleir (2003) is unequivocal that Rùm is "a pre-Gaelic name and unclear". The origins are therefore speculative, but it is known for certain that George Bullough changed the spelling to Rhum to avoid the association with the alcoholic drink rum. However, the "Rhum" spelling is used on a Kilmory gravestone dated 1843.[5] In 1991 the Nature Conservancy Council of Scotland (the forerunner to Scottish Natural Heritage) reverted to the use of Rum without the h.[3][6][7]

In the 13th century there may be references to the island as Raun-eyja and Raun-eyjum and Dean Munro writing in 1549 calls it Ronin.[8][9] Seafaring Hebrideans had numerous taboos concerning spoken references to islands. In the case of Rùm, use of the usual name was forbidden, the island being referred to as Rìoghachd na Forraiste Fiadhaich—"the kingdom of the wild forest".[10]

The island was cleared of its indigenous population prior to being mapped by the Ordnance Survey, so it is possible that many place names are speculative. Nonetheless, the significant number of Norse-derived names that exist eight centuries after Viking political control ended indicate the importance of their presence on the island. Of the nine hamlets that were mapped in 1801, seven of the names are of Norse origin.[11]

Geography

Rùm is the largest of the Small Isles, with an area of 10,463 hectares (40.40 sq mi). It had a population of only 22 in the 2001 census,[12] making it one of the most sparsely populated of all Scottish islands. There is no indigenous population; the residents are a mixture of employees of Scottish Natural Heritage and their families, together with a number of researchers and a school teacher.[13] There are a variety of small businesses on the island including accommodation providers, artists and crafters, three newly created crofts are being worked (as of 2012) with the introduction of sheep back to the island, along with pigs and poultry. Most of the residents live in the village of Kinloch, in the east of the island, which has no church or pub, but does have a village hall and a small primary school. It also has a shop and post office, which is run as a private business. There is a summer teashop open.

Kinloch is at the head of Loch Scresort, the main anchorage. Kilmory Bay lies to the north. It has a fine beach and the remains of a village, and has for some years served as the base for research into red deer (see below). The area is occasionally closed to visitors during the period of the deer rut in the autumn. The western point is the A'Bhrideanach peninsula, and to the southwest lie Wreck Bay, the cliffs of Sgorr Reidh and Harris Bay. The last is the site of the Bullough's mausoleum. The family decided the first version was inadequate and dynamited it. The second is in the incongruous style of a Greek temple. Papadil (Old Norse: "valley of the hermit") near the southern extremity has the ruins of a lodge built and then abandoned by the Bulloughs.[3]

An 1801 map produced by George Langlands identified nine villages: Kilmory to the north at the head of Glen Kilmory, Samhnan Insir just to the north between Kilmory and Rubha Samhnan Insir, Camas Pliasgiag in the northeast, "Kinlochscresort", (the modern Kinloch), Cove (Laimhrige at Bagh na h-Uamha in the east), Dibidil in the southeast, Papadil in the south, Harris in the southwest and Guirdil at the head of Glen Shellesder in the northwest.[14][15]

The island's relief is spectacular, a 19th-century commentator remarking that "the interior is one heap of rude mountains, scarcely possessing an acre of level land".[16] This combination of geology and topography make for less than ideal agricultural conditions, and it is doubtful that more than one tenth of the island has ever been cultivated. In the 18th century average land rental values on Rùm were a third those of neighbouring Eigg, and only a fifth of Canna's.[17]

Mean rainfall is high at 1,800 millimetres (71 in) at the coast and 3,000 millimetres (120 in) in the hills. Spring months are usually the driest and winter the wettest, but any month may receive the highest level of precipitation during the year.[18]

Climate

As with the rest of the British Isles and Scotland, Rùm features a strongly maritime climate with cool summers and mild winters.

There is a MetOffice weather station at Kinloch providing long term climate observations.

| Climate data for Isle of Rùm, Kinloch, 5 metres (16 ft) asl, 1971-2000, Extremes 1960- | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.7 (62.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.2 (63) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

27.9 (82.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.5 (49.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.98 (53.56) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.1 (35.8) |

2.8 (37) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

8.7 (47.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.8 (37) |

5.64 (42.15) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.5 (14.9) |

−8.9 (16) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−4 (25) |

−2.8 (27) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

1.5 (34.7) |

1.8 (35.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 303.71 (11.9571) |

228.83 (9.0091) |

257.6 (10.142) |

146.55 (5.7697) |

110.76 (4.3606) |

132.58 (5.2197) |

164.85 (6.4902) |

199.31 (7.8469) |

266.08 (10.4756) |

282.69 (11.1295) |

313.18 (12.3299) |

295.7 (11.642) |

2,689.49 (105.8854) |

| Source #1: Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute/KNMI[19] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: YR.NO[20] | |||||||||||||

Geology

The main range of hills on Rùm are the Cuillin, usually referred to as the "Rùm Cuillin", in order to distinguish them from the Cuillin of Skye. They are rocky peaks of basalt and gabbro, similar in many ways to their better-known namesakes. Geologically, Rùm is the core of a deeply eroded volcano that was active in the Paleogene era some 66 - 23 million years ago, and which developed on a pre-existing structure of Torridonian sandstone and shales resting on Lewisian gneiss.[21][22] Two of the Cuillin are classified as Corbetts: Askival and Ainshval, (Old Norse for "mountain of the ash trees" and "hill of the strongholds" respectively) and Rùm is the smallest Scottish island to have a summit above 762 metres (2,500 ft). Other hills include Hallival, Trollaval ('mountain of the trolls'), Barkeval, and Sgurr nan Gillean (Gaelic: "peak of the young men") in the Cuillin and Ard Nev, Orval, Sròn an t-Saighdeir and Bloodstone Hill in the west.[3] It is likely that only the higher peaks remained above the Pleistocene ice sheets as nunataks.[23]

Hallival and Askival are formed from an extraordinary series of layered igneous rocks created as olivine and feldspar crystals accumulated at the base of a magma chamber. The chamber eventually collapsed, forming a caldera. There are swarms of near-vertical dykes of basalt on the northwest coast between Kilmory and Guirdil, created by basaltic magma forcing its way into fissures in the pre-existing rock.[24] The western hills, although less elevated than the Cuillin, exhibit a superb collection of periglacial landforms including boulder sheets and lobes, turf-banked terraces, ploughing boulders and patterned ground. On Orval and Ard Nev the weathered basalt and granophyre has been sorted by frost heaving into circles 50 centimetres in diameter and weathering on Barkeval has produced unusual rock sculptures. On Sròn an t-Saighdeir there are large sorted granite boulder circles 2–3 metres across on the flat summit and sorted stripes on the slopes. Lava flowing away from the volcanic centre formed Bloodstone Hill, gas bubbles leaving holes in the structure that were then filled with green agate flecked with red. There are some outcrops of the pre-volcanic Lewisian gneiss near Dibidil in the southeast corner of the island, and more extensive deposits of sandstone in the north and east.[25]

Prehistory

Farm Fields, a site near Kinloch, provides some of the earliest known evidence of human occupation in Scotland. Carbonized hazelnut shells found there have been dated to the Mesolithic period at 7700-7500 BC.[26][27] At this time the landscape was dominated by alder, hazel and willow scrub.[28] A beach site above Loch Scresort has been dated to between 6500 and 5500 BC. The presence of this hunter-gatherer community may have been to take advantage of the local supplies of bloodstone, a workable material for the making of tools and weapons. There is a shell-midden at Papadil in the south and evidence of tidal fish traps at both Kinloch and Kilmory.[29]

Examination of peat cores and pollen records indicates that soil erosion (suggesting clearance of woodland for agricultural purposes) was taking place in 3470 BC and that evidence of arable cultivation by Neolithic communities exists from 2460 BC.[30] As the climate became damper, peat expanded at the expense of woodland, and post-glacial sea level changes left raised beaches around the coastline 18–45 metres above the present coastline, especially between Harris and A'Bhrideanach.[31] There are prehistoric fort sites at Kilmory, Papadil and Shellesder of uncertain date.[32]

History

Early Christian period

St Beccan of Rùm may have lived on the island for four decades from 632 AD, his death being recorded in the Annals of Ulster in 677. He is known to have been conservative on doctrinal matters and surviving examples of his poetry suggest a passionate personality.[33] He wrote of Columba:

- In scores of curraghs with an army of wretches he crossed the long-haired sea.

- He crossed the wave-strewn wild region,

- Foam flecked, seal-filled, savage, bounding, seething, white-tipped, pleasing, doleful.[34]

Simple stone pillars has been found at Kilmory and Bagh na h-Uamha ('bay of the cave') that may date from this period.[35]

Norse rule

The Norse held sway in the Small Isles from 833 until the Treaty of Perth in 1266. The Macsorley clan held tutelage in the later period of Norse rule from at least 1240, and possibly a century earlier. The only direct evidence of a Norse presence on Rùm to date is a piece of carved narwhal ivory unearthed at Bagh na h-Uamh in 1940.[3]

Medieval Scots rule

By 1346 the island was chartered to John of Islay, the Scots Lord of the Isles.[3] It is possible that during the early medieval period the island was used as a hunting reserve by the nobility (hence the 'taboo name' referred to above).[36] John of Fordun indicates that Rùm was "with excellent sport, but few inhabitants" and "a wooded and hilly island" in 1380.[37] Two hundred years later Skene noted that

Romb is ane Ile of small profit, except that it conteins mony deir, and for sustentation thairof the same is permittit unlabourit, except twa townis. It is... all hillis and waist glennis, and commodious only for hunting of deir... and will raise 6 or 7 men.[38][39]

At the same time the much smaller nearby island of Muck was able to "raise" 16 able men and in 1625 there were only three villages on Rùm, suggesting the population was being deliberately constrained.[40] Substantial stone walls built to funnel deer into pens that may date from this period still exist in the western glens.[41] During the 13th century Rùm became part of the estates of the powerful Clann Ruaidhrí for a brief period and then passed into the hands of Clanranald.[42]

16th century

By the mid-16th century, and probably a century earlier, the island was in the possession of the MacLeans of Coll. This transfer may have occurred by extortion, Allan MacRuarie of Clanranald having been held prisoner on Coll for 9 months. In 1549 Munro noted that although the island "pertained" to Coll it "obeys instantlie" to the Macleans of Duart,[9] a situation that continued for some time. In 1588 the Small Isles suffered an armed invasion by Lachlan Maclean of Duart and his band of cutthroats, including up to one hundred Spaniards shipwrecked in the aftermath of the English defeat of the Armada. He burnt and put the isles to the sword, sparing neither women nor children. At a later date a report received by King James VI indicated that Clanranald had re-occupied the island, but despite these temporary setbacks the island remained in Maclean of Coll's hands for three centuries or more.[43][44]

17th and 18th centuries

By the late 17th century Rùm's status as a hunting reserve went into decline and population numbers started to rise.[45] Black cattle were raised for export to the mainland, fish caught and barley and potatoes grown. More unusually, goats were kept by the inhabitants, the hair being sent to Glasgow and made into wigs for export to America.[46] The economy was in no small part dependent on the bounty of the sea. Edward Clarke visiting in 1797 dined on:

....milk, oatcakes and Lisbon wine. I was surprised to find wine of that species, and of a superior quality in such a hut, but they told us it was part of the freight of some unfortunate vessel wrecked near the island.[47]

This largesse notwithstanding, conditions were primitive. There was no permanent minister and when one visited he was obliged to conduct sermons in the open air, there being no church. Nor was there a mill, and leather was tanned with willow bark and dressed with sea shells due to the lack of lime.[48] The nearby smaller island of Muck was valued for land rental the same as the whole of Rùm at this time, again indicating the poverty of agriculture on Rùm.[49] The growing population of Rùm's demands on the land led to the extermination of the native red deer (Cervus elaphus) during the latter half of the 18th century.[50]

James Boswell and Samuel Johnson met with MacLean of Coll at Talisker on Skye during their 1773 excursion to the Hebrides. Boswell reported that:

After dinner he and I walked to the top of Prieshwell, a very high rocky hill, from whence there is a view of Barra, the Long Island, Bernera, the Loch of Dunvegan, part of Rùm, part of Rasay, and a vast deal of the Isle of Skye. Col, though he had come into Skye with an intention to be at Dunvegan, and pass a considerable time in the island, most politely resolved first to conduct us to Mull, and then to return to Skye. This was a very fortunate circumstance; for he planned an expedition for us of more variety than merely going to Mull. He proposed we should see the islands of Egg, Muck, Col, and Tyr-yi. In all these islands he could shew us every thing worth seeing.[51]

In the event, poor weather prevented the travellers visiting the Small Isles en route to Mull.

19th century

Apr2006.jpg)

By 1801 there were nine hamlets on the island, and its economy received a temporary boost from the kelp industry.[52] The wooded island of five hundred years before was now essentially treeless outside of Kinloch village.[53]

In 1825 the entire island was leased to Dr Lachlan Maclean, a relative of Hugh Maclean of Coll, and its inhabitants (then numbering some 450 people) were given a year's notice to quit their homes, which essentially meant an enforced leaving of the island. (Most of the population of Rùm were tenant farmers, paying rent to the island's owner; in law they neither owned the land they worked nor the houses in which they lived.) On 11 July 1826, about 300 of the inhabitants boarded two overcrowded ships—the Highland Lad and the Dove of Harmony—bound for Cape Breton in Nova Scotia, Canada. Their passage was paid by Dr Lachlan and by Maclean of Coll. The remaining population followed them in 1827 on the St. Lawrence, along with some 150 inhabitants from the island of Muck, another of Maclean of Coll's properties.[54][55] These evictions were part of a wider event that came to be known as the Highland Clearances, during which people whose culture had existed there for millennia were forced to emigrate.

In 1827, when giving evidence to a government select committee on emigration, an agent of Maclean of Coll was asked "And were the people willing to go?" "Some of them", came the reply, "Others were not very willing, they did not like to leave the land of their ancestors".[56] Years later an eyewitness, a local shepherd, was more forthcoming in his description of the events: "The people of the island were carried off in one mass, for ever, from the sea-girt spot where they were born and bred... The wild outcries of the men and heart-breaking wails of the women and children filled all the air between the mountainous shore of the bay".[57][58]

Dr Lachlan turned Rùm into a sheep farm, with its population replaced by some 8,000 blackface sheep, but the price of mutton and wool was in decline. In 1839 Lachlan was forced to relinquish his tenancy of Rùm, bankrupt, penniless and, in the words of a Cape Breton letter from 1897, "much worse off than the comfortable people he turned out of Rùm 13 years previously". The same letter described Lachlan as "the Curse and Scourge of the Highland Crofters".[59]

In 1844 the visiting geologist, Hugh Miller, wrote:

The single sheep farmer who had occupied the holdings of so many had been unfortunate in his speculations, and had left the island: the proprietor, his landlord seemed to have been as little fortunate as his tenant, for the island itself was in the market; and a report went current at the time that it was on the eve of being purchased by some wealthy Englishman, who purposed converting it into a deer forest. How strange a cycle![60]

MacLean of Coll sold the island to the Marquess of Salisbury in 1845, who converted it into a sporting estate. The island was then owned by the Campbell family from 1870 to 1888, when John Bullough, a cotton machinery manufacturer and self-made millionaire from Accrington in Lancashire, acquired the island, and continued to use it for recreational purposes. The estate's prospectus for the 1888 sale described Rùm as "the most picturesque of the islands which lie off the west coast of Scotland" and "as a sporting estate it has at present few equals". It gave its population as between 60 and 70, all either shepherds or estate workers and their families. There were no crofts on the island.[61] When Bullough died in 1891 he was buried on Rùm, in a rock-cut mausoleum under an octagonal stone tower. This was later demolished and his sarcophagus moved into an elaborate mausoleum modelled as a Greek temple. He was succeeded in the ownership of Rùm by his son, George Bullough.

20th century

George Bullough (later Sir George), built Kinloch Castle in 1900 using sandstone quarried at Annan in Dumfries and Galloway[62] (some sources say the stone was from Arran).[63]

At this time there were about 100 people employed on the estate. Fourteen under-gardeners, who were paid extra to wear kilts, worked on the extensive grounds that included a nine-hole golf course, tennis and squash courts, heated turtle and alligator ponds and an aviary including birds of paradise and humming birds. Soil for the grounds was imported from Ayrshire and figs, peaches, grapes and nectarines were grown in greenhouses. The interior boasted an orchestrion that could simulate the sounds of brass, drum and woodwind, an air-conditioned billiards room, and a jacuzzi. This opulence could not be sustained indefinitely. The Bullough finances gradually declined in the 1920s, and their interest in, and visits to Rùm decreased. Sir George died in France in July 1939—he was interred in the family mausoleum on Rùm. His widow continued to visit Rùm as late as 1954. She died in London in 1967, aged 98, and was buried next to her husband in the Rùm mausoleum. In 1957 Lady Bullough had sold the whole island, save for the mausoleum, but including the castle and its contents, to the Nature Conservancy Council (now Scottish Natural Heritage) for the "knock-down price of £23,000"[64] on the understanding that it would be used as a national nature reserve.[3][65][66]

Overview of population trends

| Year | 1595 | 1625 | 1728 | 1755 | 1764 | 1768 | 1772 | 1786 | 1794 | 1807 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1891 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 30-5 | 17+ | c.179 | 206 | 304 | 302 | 325 | 300 | 443 | 443 | 394 | 134 | 124 | 53 | 26 | 22[67] | 22[2] |

Source: Rixson (2001) unless otherwise stated[68]

Ecology

Rùm is an important study site for research in ecology and numerous academic papers have been produced based on work undertaken on the island. In addition to its status as nature reserve, Rùm was designated a Biosphere Reserve from 1976 to 2002,[69] a Site of Special Scientific Interest in 1987, and has seventeen sites scheduled as nationally important ancient monuments.[65]

Red deer

The red deer population has been the subject of research for many years, recently under the leadership of Tim Clutton-Brock of the University of Cambridge.[70] These efforts are based at the remote bay of Kilmory in the north of the island. It has been important in the development of sociobiology and behavioural ecology, particularly in relation to the understanding of aggression through game theory.

Ponies, goats and cattle

The island has small herds of ponies, feral goats (Capra hircus) and Highland cattle. The pony herd, which now numbers about a dozen animals, was first recorded on the island in 1772, and in 1775 they were described as being "very small, but a breed of eminent beauty".[71] They are small in stature, averaging only 13 hands in height and all have a dark stripe down their backs and zebra stripes on their forelegs. These features have led to speculation that they may be related to primitive northern European breeds, although it is more likely that they originate from the western Mediterranean. It is sometimes claimed that they are descended from animals that travelled with the Spanish Armada, although it is probable that they arrived by more conventional means. The goat stocks were improved for stalking in the early 20th century and acquired a reputation for the size of their horns and the thickness of their fleeces. The flock of about 200 spends most of its time on the western sea cliffs. The native cattle were re-introduced in 1970, having been absent since the 19th century clearances. The herd of 30 grazes in the Harris area from September to June, and further north in Glen Shellesder in the summer months.[15][72][73]

Other fauna

Rùm is also noted for its bird life. The population of 70,000 Manx shearwaters is one of the largest breeding colonies in the world. These migrating birds that spend their winters in the South Atlantic off Brazil, and return to Rùm every summer to breed in underground burrows high in the Cuillin Hills. White-tailed sea eagles were exterminated on the island by 1912 and later became extinct in Scotland. A programme of reintroduction began in 1975, and within ten years 82 young sea eagles from Norway had been released. There is now a successful breeding population in the wild.[65]

There are brown trout, European eel and three-spined stickleback in the streams, and salmon occasionally run in the Kinloch River.[74] The only amphibian found on Rùm is the palmate newt and the only reptile native to Rùm is the common lizard. Invertebrates are diverse and have been studied there since 1884, numerous species of damsel fly, dragonfly, beetle, butterflies, moths etc. having been recorded. Several rare upland species are found on the ultrabasic slopes of Barkeval, Hallival and Askival including the ground beetles Leistus montanus and Amara quenseli. The midge (Culicoides impunctatus), a biting gnat, occurs in "unbelievable numbers".[75]

In October 2006 the popular Autumnwatch series on BBC television showed coverage of the deer rut at Kilmory Bay.[76]

A 1.5 hectare patch of brown earth soil at the abandoned settlement of Papadil is home to a thriving population of earthworms, which are rare in the elsewhere poor soil of the island.[77] Some individuals of Lumbricus terrestris have reached tremendous sizes, with the largest weighing 12.7 grams. This is speculated to be due to the good quality soil, and absence of predators.[78]

Flora

A tree nursery was established at Kinloch in 1960 in order to support a substantial programme of re-introducing twenty native species including silver birch, hawthorn, rowan and holly.[79] The forested area, which consists of over a million re-introduced native trees and shrubs, is essentially confined to the vicinity of Kinloch and the slopes near this site surrounding Loch Scresort and on nearby Meall á Ghoirtein.[3] The island's flora came to widespread attention with the 1999 publication of the book A Rum Affair by Karl Sabbagh, a British writer and television producer. The book told of a long-running scientific controversy over the alleged discovery of certain plants on Rùm by botanist John William Heslop-Harrison—discoveries that are now considered to be fraudulent. Heslop Harrison is widely believed to have placed many of these plants on the island himself to provide evidence for his theory about the geological development of the Hebridean islands.[80] Nonetheless, the native flora offers much of interest. There are rare arctic sandwort and alpine pennycress, endemic varieties of the heath spotted-orchid and eyebright, as well as more common species such as sundew, butterwort, blue heath milkwort and roseroot.[3] A total of 590 higher plant and fern taxa have been recorded.[81]

Economy, transport and culture

Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The entire island is owned and managed as a single estate by Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH). As noted above, the island has a transient population comprising employees of SNH and their families, researchers, and a teacher. Until recently SNH have been opposed to the development of the island as a genuine community, but there has been a change in approach since the beginning of 2007. Di Alexander, development manager for the Highlands Small Communities Housing Trust has said: "It has been clear for many years that the small community on Rùm needs to increase and diversify its housing supply away from exclusively SNH-tied housing. Even a couple of new rented houses could make such a difference to the community's wellbeing."[82]

Surprisingly perhaps, on an 10,500 hectares (26,000 acres) estate with a population less than thirty, an issue has been lack of land for building. However, an SNH spokesman has stated "Once we are clear what the trust's priorities are, we will release the land". The Prince's Regeneration Trust, which is drawing up a conservation plan for Kinloch Castle, may also make proposals for renewable energy generation on the island.[82]

In 2008 a "Rùm Task Group", chaired by Lesley Riddoch, was created to generate proposals for advancing community development opportunities. It reported to Mike Russell MSP the Minister for Environment in the Scottish Government, and in June a plan was announced to establish a locally-run trust with the aim of reintroducing crofting settlements to the area around Kinloch village.[83][84][85] In December it was announced that £250,000 of land and buildings are likely to be placed into community ownership, subject to a ballot of the electorate in January 2009.[86]

A Caledonian MacBrayne ferry, MV Lochnevis, links Rùm and the neighbouring Small Isles of Canna, Eigg and Muck, to the mainland port of Mallaig some 17 miles (27 km) and 1½ hours sailing time away.[87] The Lochnevis has a landing craft-style stern ramp allowing vehicles to be driven onto and off the vessel at a new slipway constructed in 2001. However, visitors are not normally permitted to bring vehicles to the Small Isles. During the summer months the islands are also served by Arisaig Marine's ferry MV Sheerwater from Arisaig, 10 miles (16 km) south of Mallaig.

The best anchorage is Loch Scresort, with other bays offering only temporary respites from poor weather.[3][88] Robert Buchanan writing in the 19th century described it as:

As sweet a little nook as ever Ulysses mooned away a day in, during his memorable voyage homeward. Though merely a small bay, about a mile in breadth, and curving inland for a mile and a half, it is quite sheltered from all winds save the east, being flanked to the south and west by Haskeval and Hondeval, and guarded on the northern side by a low range of heathery slopes. In this sunny time, the sheep are bleating from the shores, the yacht lies double, yacht and shadow, and the bay is painted richly with the clear reflection of the mountains.[89]

In the summer of 2002 a reality TV programme titled Escape from Experiment Island was filmed on the island. This short-lived show (6 episodes) was produced by the BBC in conjunction with the Discovery Channel. The show was to piggyback on the success of Junkyard Wars by having the teams build vehicles to escape from the island.[90]

See also

- Small Isles

- Beccán mac Luigdech

- Religion of the Yellow Stick

- Geology of Scotland

- Timeline of prehistoric Scotland

Footnotes

- 1 2 Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- 1 2 3 National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013) (pdf) Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland - Release 1C (Part Two). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland’s inhabited islands". Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Haswell-Smith (2004) pages 138-143.

- ↑ Ordnance Survey. Get-a-map (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure. Ordinance Survey. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Love (2002) p?.

- ↑ Ross, David (2007) Dictionary of Scottish Place-names. Edinburgh. Birlinn/Scotland on Sunday.

- ↑ Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012. .

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 88.

- 1 2 Munro, D. (1818) Description of the Western Isles of Scotland called Hybrides, by Mr. Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles, who travelled through most of them in the year 1549. Miscellanea Scotica, 2.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 110.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) pages 67 and 70.

- ↑ "Scotland's Island Populations". Scottish Islands Federation. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ↑ "Assessment of Social Capital on Rum and the Small Isles" (PDF). Centre for Rural Economy, Newcastle University. 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 142.

- 1 2 Virtanaen, R., Edwards, G.R. and Crawley M.J. (2002) Red deer management and vegetation on the Isle of Rum (pdf) Journal of Applied Ecology 39 572-83.

- ↑ MacCulloch, J. (1824) The Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland. Vol. IV. London.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 136, quoting Walker's Report on the Hebrides of 1764.

- ↑ Clutton-Brock, T. and Ball, M.E. (1987) pages 2-3.

- ↑ "Rum climate Extremes". KNMI.

- ↑ "1971-2000 Averages for Kinloch". YR.NO.

- ↑ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 150.

- ↑ Emeleus, C.H. "The Rhum Volcano" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) page 12.

- ↑ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 285.

- ↑ Emeleus, C.H. "The Rhum Volcano" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) page 11.

- ↑ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 194 and 284-5.

- ↑ Edwards, Kevin J. and Whittington, Graeme "Vegetation Change" in Edwards & Ralston (2003) page 70.

- ↑ In 2004 the remains of a large camp were found at Cramond in West Lothian, dated to 8500 BC, fully a millennium earlier than the Rùm site. See "The Megalithic Portal and Megalith Map: Rubbish dump reveals time-capsule of Scotland's earliest settlements" megalithic.co.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ↑ McKirdy et al. (2007) page 196.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) pages 1-7.

- ↑ Ballantyne, Colin K, and Dawson, Alastair G. "Geomorphology and Landscape Change" in Edwards & Ralston (2003) page 42.

- ↑ McKirdy et al. (2007) pages 196, 214 and 286.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 2.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) pages 21-25.

- ↑ "Tiugraind Beccain" in Clancy, T.O. and Markus, G. eds. (1995) Iona- The Earliest Poetry of A Celtic Monastery quoted by Rixson (2001) page 25.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 35.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 99.

- ↑ John of Fordun (c. 1380) Scotichronicon quoted in Rixson (2001) pages 100 and 154.

- ↑ Skene The Description of the Isles of Scotland, 1577-95 quoted in Rixson (2001) page 100.

- ↑ English translation from Lowland Scots: "Rum is an isle of small profit, except that it contains many deer, and to sustain them they are free to roam, except for two villages. It is... all hills and waste valleys, and commodious only for hunting of deer... and will raise 6 or 7 men (for war)."

- ↑ Rixson (2001) pages 100-1.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 111.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 93.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) pages 117-9.

- ↑ Love, J.A. "Rhum's Human History" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) page 30.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) pages 93 and 107-8.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 141, quoting Walker's Report on the Hebrides of 1764.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 15.

- ↑ Pennant, Thomas (1772) A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 81.

- ↑ Clutton-Brock, T. and Guinness F.E. "Red Deer" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) page 95.

- ↑ Boswell, James (1775) Journal of A Tour to the Hebrides With Samuel Johnson, LL.D.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) pages 142-4.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 155.

- ↑ Love, J.A. "Rhum's Human History" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) pages 39-40.

- ↑ Love (2002), page ?

- ↑ Love (2002), page 129.

- ↑ Waugh, Edwin (1882) The Limping Pilgrim quoting an unknown shepherd. Recorded in Love, J.A. "Rhum's Human History" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) page 40.

- ↑ Description of the Suisnish clearances on nearby Skye: "The Skye and Raasay Clearances – 1853". Video from A history of Scotland: This Land is Our Land. BBC. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ Love (2002), page 128.

- ↑ Miller, Hugh (1845) The Cruise of the Betsey. National Museums Of Scotland: (2000 reprint). ISBN 1-901663-54-X

- ↑ Love (2002) pages 222-23.

- ↑ Scottish Natural Heritage (1999) page 9.

- ↑ See for example, McKirdy et al. (2007) page 144.

- ↑ Love (2002) page 260.

- 1 2 3 "The Story of Rum National Nature Reserve" (pdf) SNH. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 205.

- ↑ General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ↑ Rixson (2001) page 169, quoting a variety of sources.

- ↑ "Four biosphere reserves delisted". (26 March 2002) Scottish Government. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ↑ See for example Clutton-Brock, T.H.; Coulson, T.N.; Milner-Gulland, E. J; Thomson, D.; Armstrong, H.M.; [www.iccs.org.uk/wp-content/papers/Clutton-Brock2002Nature.pdf Sex differences in emigration and mortality affect optimal management of deer populations.] (2002) (pdf) Nature 415: 633-637.

- ↑ Gordon, I., Dunbar, R., Buckland D., and Miller, D. "Ponies, Cattle and Goats" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) pages 110-6. The pony quotation is Maclean of Coll, as told to Samuel Johnson.

- ↑ Pennant, Thomas (1775) A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides 1772. Republished by Birlinn, Edinburgh (1998).

- ↑ Gordon, I., Dunbar, R., Buckland D., and Miller, D. "Ponies, Cattle and Goats" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) pages 110-6.

- ↑ Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) page 143.

- ↑ Wormell, P. "Invertebrates of Rhum" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) pages 64-74.

- ↑ "Autumnwatch animal action" BBC. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- ↑ Butt, K.R. (2015). "An oasis of fertility on a barren island: Earthworms at Papadil, Isle of Rum" (PDF). The Glasgow Naturalist. 26 (2). Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ Roberts, Elizabeth (16 January 2016). "Giant worms discovered on remote Scottish island". The Telegraph. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

Dr Butt believes the Rum worms are bigger than average due to their remote, undisturbed location, with good quality soil. Rum also lacks predators such as badgers, moles, hedgehogs and foxes which would usually gobble the worms before they had chance to grow into monsters.

- ↑ Ball. M.E. "Botany, Woodland and Forestry" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) page 57.

- ↑ Sabbagh, Karl (1999)

- ↑ Ball. M.E. "Botany, Woodland and Forestry" in Clutton-Brock and Ball (1987) page 48.

- 1 2 O'Connell, Sanjida (17 October 2007) "Seeking sanctuary" The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ↑ Ross, John (7 February 2008) " 'Forbidden Isle' gets a new champion". Edinburgh. The Scotsman.

- ↑ Riddoch, Lesley, (8 June 2008) "Regenerating Rum" London. The Guardian.

- ↑ "Rum to be handed back to islanders" (18 June 2008) Local People Leading, quoting The Times. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ↑ Ross, David (10 December 2008) "Just 23 can vote... but islanders of Rum are ready to take control". Glasgow. The Herald.

- ↑ "Small Isles ferry timetable" Caledonian MacBrayne. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ↑ "Island and Wildlife Cruises" Arisaig Marine. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ↑ Buchanan, Robert (1872) The Hebrid Isles quoted in Cooper, Derek (1979) Road to the Isles: Travellers in the Hebrides 1770-1914. London. Routledge & Kegan Paul. Page 117.

- ↑ "US gets new BBC realilty show". BBC News. 21 May 2002. Retrieved 27 October 2007. The misspelling of 'reality' is in the original.

References

- Clutton-Brock, T. and Ball, M.E. (Eds) (1987) Rhum: The Natural History of an Island. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-85224-513-0

- Edwards, Kevin J. & Ralston, Ian B.M. (Eds) (2003) Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC—AD 1000. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1736-1

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Love, John A. (2002) Rum: A Landscape Without Figures. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-224-7

- McKirdy, Alan Gordon, John & Crofts, Roger (2007) Land of Mountain and Flood: The Geology and Landforms of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-357-X

- Rixson, Dennis (2001) The Small Isles: Canna, Rum, Eigg and Muck. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-154-2

- Sabbagh, Karl (1999) A Rum Affair. London. Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9277-8

- Scottish Natural Heritage (1999) Kinloch Castle Perth. SNH Publications. ISBN 1-85397-043-3

Further reading

- Cameron, Archie (1998) Bare Feet and Tackety Boots: A Boyhood on the Island of Rum. Luath Press. ISBN 0-946487-17-0.

- John A. Love (2001) Rum: A Landscape Without Figures. Edinburgh. Birlinn.

- Pearman, D.A.; Preston, C.D.; Rothero, G.P.; and Walker, K. J. (2008) The Flora of Rum. Truro. D.A. Pearman. ISBN 978-0-9538111-3-7

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Rum. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rùm. |

- Photos

- Isle of Rum website

- Rum National Nature Reserve

- Site Management statement for Rùm Site of Special Scientific Interest

Coordinates: 57°0′N 6°21′W / 57.000°N 6.350°W