Saltwater crocodile

| Saltwater crocodile Temporal range: 4.5–0 Ma Early Pliocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Crocodylidae |

| Genus: | Crocodylus |

| Species: | C. porosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801 | |

| |

| Range of the saltwater crocodile in black | |

The saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), also known as the estuarine crocodile, Indo-Pacific crocodile, marine crocodile, sea crocodile or informally as saltie,[2] is the largest of all living reptiles, as well as the largest terrestrial and riparian predator in the world. Males of this species can reach sizes up to at least 6.30 m (20.7 ft) and possibly up to 7.0 m (23.0 ft) in length.[3] However, an adult male saltwater crocodile rarely reaches and exceeds a size of 6 m (19.7 ft) weighing 1,000 to 1,200 kg (2,200–2,600 lb).[4] Females are much smaller and often do not surpass 3 m (9.8 ft).[4] As its name implies, this species of crocodile can live in marine environments, but usually resides in saline and brackish mangrove swamps, estuaries, deltas, lagoons, and lower stretches of rivers. They have the broadest distribution of any modern crocodile, ranging from the eastern coast of India, throughout most of Southeast Asia, and northern Australia.

The saltwater crocodile is a formidable and opportunistic hypercarnivorous apex predator. Most prey are ambushed and then drowned or swallowed whole. It is capable of prevailing over almost any animal that enters its territory, including other apex predators such as sharks, varieties of freshwater and marine fish including pelagic species, invertebrates, such as crustaceans, various reptiles, birds and mammals, including humans.[5][6] Due to their size, aggression and distribution, saltwater crocodiles are regarded as the most dangerous extant crocodilian to humans.[7][8]

Taxonomy and evolution

Crocodylus porosus is believed to have a direct link to similar crocodilians that inhabited the shorelines of the supercontinent Gondwana (which included what is now the Australian continent) as long ago as 98 million years and were survivors of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. Fossils of Isisfordia, discovered in outback western Queensland (once a vast inland sea) though smaller in size, show attributes of direct lineage to Crocodylus porosus, suggesting it occupied a similar habitat, with vertebrae indicating it shared the ability to death roll during feeding.[9][10][11] Incomplete fossil records make it difficult to accurately trace the emergence of the species. The genome was fully sequenced in 2007.[12] The earliest fossil evidence of the species dates to around 4.0–4.5 million years ago [13] and no subspecies are known. Scientists estimate that C. porosus is an ancient species that could have diverged from 12 to 6 million years ago.[14][15][16] Genetic research has unsurprisingly indicated that the saltwater crocodile is related relatively closely to other living species of Asian crocodile, although some ambiguity exists over what assemblage it could be considered part of based on variable genetic results. Other relatively broad-snouted species such as Mugger (C. palustris) and Siamese crocodiles (C. siamensis) seem to be the most likely candidates to bear the closest relation among living species.[14][17][18][19]

Possible subspecies and status as a species complex

Currently, most sources state that the saltwater crocodile has no subspecies.[20] However, based largely on morphological variability, some have claimed that not only are there subspecies but that C. porosus actually houses a species complex. In 1844, S. Müller and H. Schlegel attempted to describe crocodiles from Java and Borneo as a new species which they named C. raninus, subsequently given the informal common names of the Indonesian crocodile or Bornean crocodile. According to Ross (1992), specimens of C. raninus can reliably be distinguished both from Siamese crocodiles and true saltwater crocodiles on the basis of the number ventral scales and on the presence of four postoccipital scutes which are often absent in true saltwater crocodiles.[19][21][22] Another attempt to derive a species came from Australia, Wells & Wellington (1985), and was based upon large-bodied, relatively large-headed and short-tailed crocodiles from Australia. The type specimen reported for this so-called species was a crocodile nicknamed "Sweetheart" that was inadvertently killed in 1979 (drowned after overly-anesthetized in an attempt to relocate it after it had taken to attacking boats). However, this "species", C. pethericki, has later been largely considered as a misinterpretation of the physiological changes undergone by very large male crocodiles. However, Wells and Wellington's assertion that the Australian saltwater crocodiles may at least be distinctive enough from northern Asian saltwater crocodiles to warrant subspecies status, as could raninus from other Asian saltwater crocodiles, has been considered to possibly bear validity.[19][23][24][25]

Characteristics

The saltwater crocodile has a wide snout compared to most crocodiles. However, it has a longer muzzle than the mugger crocodile; its length is twice its width at the base.[26] The saltwater crocodile has fewer armour plates on its neck than other crocodilians. On this species, a pair of ridges runs from the eyes along the centre of the snout. The scales are oval in shape and the scutes are either small compared to other species or commonly are entirely absent. In addition, an obvious gap is also present between the cervical and dorsal shields, and small, triangular scutes are present between the posterior edges of the large, transversely arranged scutes in the dorsal shield. The relative lack of scutes is considered an asset useful to distinguish saltwater crocodiles in captivity or in illicit leather trading, as well as in the few areas in the field where sub-adult or younger saltwater crocodiles may need to be distinguished from other crocodiles.[27][28] The adult saltwater crocodile's broad body contrasts with that of most other lean crocodiles, leading to early unverified assumptions the reptile was an alligator.[29] The head is very large. The largest skull sized that could be scientifically verified was for a specimen in the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle sourced to Cambodia, the skull length for this specimen was 76 cm (30 in) (female skull lengths of over 45 cm (18 in) are exceptional), with a mandibular length of 98.3 cm (38.7 in) and a maximum width across the skull (near the base) of 48 cm (19 in). The length of the specimen this came from is not known but based on skull-to-total-length ratios for very large saltwater crocodiles its length was presumably somewhere in the 7 m (23 ft 0 in) range.[30][31][32] Although it is the largest overall living crocodilian and reptile, other crocodilians may have a proportionately longer skull, namely the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) and the false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii), skull lengths in the latter have been verified up to 84 cm (33 in) (the largest crocodilian skull verified for a living species), although both of these thin-snouted species have less massive skulls and considerably less massive bodies than the saltwater crocodile.[32] The teeth are also long, with the largest teeth (the fourth tooth from the front on the lower jaw) having been measured at up to 9 cm (3.5 in) in length.[33][34] If detached from the body, the head of a very large male crocodile can reportedly weigh over 200 kg (440 lb) alone, including the large muscles and tendons at the base of the skull that lend the crocodile its massive biting strength.[35]

Young saltwater crocodiles are pale yellow in colour with black stripes and spots on their bodies and tails. This colouration lasts for several years until the crocodiles mature into adults. The colour as an adult is much darker greenish-drab, with a few lighter tan or grey areas sometimes apparent. Several colour variations are known and some adults may retain fairly pale skin, whereas others may be so dark as to appear blackish. The ventral surface is white or yellow in colour on saltwater crocodiles of all ages. Stripes are present on the lower sides of their bodies, but do not extend onto their bellies. Their tails are grey with dark bands.[36][37]

Size

Saltwater crocodiles are the largest extant terrestrial and riparian predators in the world. However, they start life fairly small. Newly hatched saltwater crocodiles measure about 28 cm (11 in) long and weigh an average of 71 g (2.5 oz).[38] This distinct contrast in size between hatchlings and adult males is one of the greatest in terrestrial vertebrates. By their second year, young crocodiles grow to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long and weigh 2.5 kg (5.5 lb).[38] Males reach sexual maturity around 3.3 m (10 ft 10 in) at around 16 years of age, while females reach sexual maturity at 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) and 12–14 years of age.[37] The weight of a crocodile increases exponentially as length increases.[note 1] This explains why individuals at 6 m (19 ft 8 in) can weigh more than twice that of individuals at 5 m (16 ft).[29] In crocodiles, linear growth eventually decreases and they start getting bulkier at a certain point.[39] Dominant males also tend to outweigh others, as they maintain prime territories with access to better, more abundant prey.

Male size: An adult male saltwater crocodile, from young adults to older individuals, ranges 3.5 to 6 m (11 ft 6 in to 19 ft 8 in) in length, weighing 200 to 1,000 kg (440–2,200 lb).[40][41][42] On average, adult males range 4.3 to 4.9 m (14 ft 1 in to 16 ft 1 in) in length and weigh 408 to 522 kg (899–1,151 lb).[35] However average size largely depends on the location, habitat, and human interactions, thus changes from one study to another, when figures of each study are viewed separately. In one case, Webb and Manolis (1989) attributed the average weight of adult males in Australian tidal rivers as only 240 to 350 kg (530 to 770 lb) at lengths of 4 to 4.5 m (13 ft 1 in to 14 ft 9 in) during the 1980s, possibly representing a reduced body mass due to the species being in recovery after decades of overhunting at that stage, as males this size would typically weigh about 100 kg (220 lb) heavier.[41] Rarely very large, aged males can exceed 6 m (19 ft 8 in) in length and weigh well over 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[29][32][43] The largest confirmed saltwater crocodile on record drowned in a fishing net in Papua New Guinea in 1979, its dried skin plus head measured 6.2 m (20 ft 4 in) long and it was estimated to have been 6.3 m (20 ft 8 in) when accounting for shrinkage and a missing tail tip.[3][44] However, according to evidence, in the form of skulls coming from some of the largest crocodiles ever shot, the maximum possible size attained by the largest members of this species is considered to be 7 m (23 ft 0 in).[3][29] A research paper on the morphology and physiology of crocodilians by the government of Australia estimates that saltwater crocodiles approaching sizes of 7 m (23 ft 0 in) would weigh around 2,000 kg (4,400 lb).[45] Due to extensive poaching during the 20th century, such individuals are extremely rare today in most areas, as it takes a long time for the crocodiles to attain those sizes. Also, a possible earlier presence of particular genes may have led to such large-sized saltwater crocodiles, genes that were ultimately lost from the overall gene pool due to extensive hide and trophy hunting in the past. However, with recent restoration of saltwater crocodile habitat and reduced poaching, the number of large crocodiles is increasing, especially in Odisha. This species is the only extant crocodilian to regularly reach or exceed 5.2 m (17 ft 1 in).[32][35] A large male from Philippines, named Lolong, was the largest saltwater crocodile ever caught and placed in captivity. He was 20 ft 3 in (6.17 m), and weighed 2,370 lbs (1,075 kg). Believed to have eaten two villagers, Lolong was captured on 3 September 2011, and died in captivity on 10 February 2013.

Female size: Adult females typically measure from 2.7 to 3.1 m (8 ft 10 in to 10 ft 2 in) in total length and weigh 76 to 103 kg (168 to 227 lb).[46][47][48] The largest female on record measured about 4.2 m (13 ft 9 in) in total length.[35] Due to the extreme sexual dimorphism of the species as contrasted with the more modest size dimorphism of other species, the average length of the species is only slightly more than some other extant crocodilians at 3.8–4 m (12 ft 6 in–13 ft 1 in).[20][26][49]

Distribution and habitat

.jpg)

The saltwater crocodile is one of the three crocodilians found in India, the other two being the more regionally widespread, smaller mugger crocodile and the narrow-snouted, fish-eating gharial.[50] Apart from the eastern coast of India, the saltwater crocodile is extremely rare on the Indian subcontinent.[51] A large population is present within the Bhitarkanika Wildlife Sanctuary of Odisha and they are known to be present in smaller numbers throughout the Indian and Bangladeshi portions of the Sundarbans. The saltwater crocodile also persists in bordering Bangladesh as does the mugger and gharial.[52][53] Populations are also present within the mangrove forests and other coastal areas of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India. Saltwater crocodiles were once present throughout most of the island of Sri Lanka, but remain mostly within protected areas such as Yala National Park, which also has a large population of mugger crocodiles.

In northern Australia (which includes the northernmost parts of the Northern Territory, Western Australia, and Queensland), the saltwater crocodile is thriving, particularly in the multiple river systems near Darwin such as the Adelaide, Mary, and Daly Rivers, along with their adjacent billabongs and estuaries.[54] The saltwater crocodile population in Australia is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000 adults. In Australia, the species coexists with the smaller, narrow-snouted Johnston's or freshwater crocodile (C. johnsoni).[55] Their range extends from Broome in Western Australia through the entire Northern Territory coast all the way south to Rockhampton in Queensland. The Alligator Rivers in the Arnhem Land region are misnamed due to the resemblance of the saltwater crocodile to alligators as compared to freshwater crocodiles, which also inhabit the Northern Territory.[56] In New Guinea, they are also common, existing within the coastal reaches of virtually every river system in the country, such as the Fly River, along with all estuaries and mangroves, where they overlap in range but rarely in actuality or habitat with the rarer, less aggressive New Guinea crocodile (C. novaeguineae). They are also present in varying numbers throughout the Bismarck Archipelago, the Kai Islands, the Aru Islands, the Maluku Islands and many other islands within the region, including Timor, and most islands within the Torres Strait.[57]

The saltwater crocodile was historically known to be widespread throughout Southeast Asia, but is now extinct throughout much of this range. This species has not been reported in the wild for decades in most of Indochina and is extinct in Thailand,[58] Laos,[59] Vietnam,[60] and possibly Cambodia.[61] The status of this species is critical within much of Myanmar, but a stable population of many large adults is present in the Irrawaddy Delta.[62] Probably, the only country in Indochina still harbouring wild populations of this species is Myanmar.[63] Although saltwater crocodiles were once very common in the Mekong Delta (from where they disappeared in the 1980s) and other river systems, the future of this species in Indochina is now looking grim. However, it is also the least likely of crocodilians to become globally extinct due to its wide distribution and almost precolonial population sizes in Northern Australia and New Guinea.

The saltwater crocodile has been long extinct in China, where it inhabited the southern coastal areas from Fujian province in the north to the border of Vietnam.[64] References to large crocodiles that preyed on both humans and livestock appeared during the Han and Song Dynasties, where it occurred in the lower Pearl River near present-day Hong Kong and Macau, the Han River, the Min River in the north, portions of coastal Guangxi province and Hainan Island.[26] The presence of crocodiles in Fujian province represent the northernmost distribution of the species.[65]

The population is sporadic in Indonesia and Malaysia, with some areas harbouring large populations (Borneo and Sumatra, for example) and others with very small, at-risk populations (e.g., Peninsular Malaysia).[66] Despite the close proximity to the crocodile hotbed of northern Australia, crocodiles no longer exist in Bali. This species is also reportedly extinct on Lombok, Komodo, and most of Java.[67] In the southern Malaysian Peninsula as well as Borneo, salwater crocodiles may co-exist with the relatively narrow-snouted false gharial (as well as on Sumatra) and the closely related but usually smaller Siamese crocodile (as well as in Java).[68][69] A small population may remain within Ujung Kulon National Park in western Java. The saltwater crocodile is also present in very limited parts of the South Pacific, with an average population in the Solomon Islands, a very small and soon to be extinct population in Vanuatu (where the population officially stands at only three) and a decent but at-risk population (which may be rebounding) in Palau. They once ranged as far west as the east coast of Africa to the Seychelles Islands. These crocodiles were once believed to be a population of Nile crocodiles, but they were later proven to be C. porosus.[29]

Because of its tendency to travel very long distances at sea, individual saltwater crocodiles have been known to occasionally appear in areas far away from their general range. Vagrant individuals have historically been reported on New Caledonia, Fiji, and in Asian waters possibly swam with Kuroshio Current,[70] reaching such as at Iwo Jima, Hachijō-jima, Amami Ōshima, Iriomote-jima (residences by several individuals along Urauchi River from Bakumatsu to Meiji until being hunted by locals were suggested),[71] pelagic watetrs off Shima, Mie, Miura Peninsula,[70] and even in the relatively frigid Sea of Japan (thousands of miles from their native territory.)[72] In late 2008-early 2009, a handful of wild saltwater crocodiles were verified to be living within the river systems of Fraser Island, hundreds of kilometres from, and in much cooler water than, their normal Queensland range. These crocodiles did indeed migrate south to the island from northern Queensland during the warmer wet season and presumably returned to the north upon the seasonal temperature drop. Despite the surprise and shock within the Fraser Island public, this is apparently not new behaviour, and in the distant past, wild crocodiles had been reported occasionally appearing as far south as Brisbane during the warmer wet season.

Saltwater crocodiles generally spend the tropical wet season in freshwater swamps and rivers, moving downstream to estuaries in the dry season, and sometimes travelling far out to sea. Crocodiles compete fiercely with each other for territory, with dominant males in particular occupying the most eligible stretches of freshwater creeks and streams. Junior crocodiles are thus forced into the more marginal river systems and sometimes into the ocean. This explains the large distribution of the animal (ranging from the east coast of India to northern Australia), as well as its being found in the odd places on occasion (such as the Sea of Japan). Like all crocodiles, they can survive for prolonged periods only in warm temperatures, and crocodiles seasonally vacate parts of Australia if cold spells hit.[8]

Biology and behaviour

The primary behaviour to distinguish the saltwater crocodile from other crocodiles is its tendency to occupy salt water. Though other crocodiles also have salt glands that enable them to survive in saltwater, a trait which alligators do not possess, most other species do not venture out to sea except during extreme conditions.[73] The only other species to display regular seagoing behaviour is the American crocodile (C. acutus), but the American version is still not considered to be as marine-prone as the saltwater crocodile. As its alternate name "sea-going crocodile" implies, this species travels between areas separated by sea, or simply relies on the relative ease of travelling through water in order to circumvent long distances on the same land mass, such as Australia. In a similar fashion to migratory birds using thermal columns, saltwater crocodiles use ocean currents to travel long distances.[74] In a study, 20 crocodiles were tagged with satellite transmitters; 8 of these crocodiles ventured out into open ocean, in which one of them travelled 590 km (370 mi) along the coast – from the North Kennedy River on eastern coast of Far North Queensland, around Cape York Peninsula, to the west coast in the Gulf of Carpentaria – in 25 days.[74] Another specimen, a 4.84 m (15 ft 11 in)-long male, travelled 411 km (255 mi) in 20 days. Without having to move around much, sometimes simply by floating, the current-riding behaviour allows for the conservation of energy. They will even interrupt their travels, residing in sheltered bays for a few days, when the current is against the desired direction of travel, until the current changes direction.[74] Crocodiles also travel up and down in river systems, periodically.[74]

_(8851850268).jpg)

While most crocodilians are social animals sharing basking spots and food, saltwater crocodiles are more territorial and are less tolerant of their own kind; adult males will share territory with females, but drive off rival males. Saltwater crocodiles mate in the wet season, laying eggs in a nest consisting of a mound of mud and vegetation. The female guards the nest and hatchlings from predators.

Generally very lethargic, a trait which helps it survive months at a time without food, the saltwater crocodile will usually loiter in the water or bask in the sun during much of the day, preferring to hunt at night. A study of seasonal saltwater crocodile behaviour in Australia indicated that they are more active and more likely to spend time in the water during the Australian summer; conversely, they are less active and spend relatively more time basking in the sun during the winter.[75] Saltwater crocodiles, however, are among the most active of all crocodilians, spending more time cruising and active, especially in water. They are much less terrestrial than most species of crocodiles, spending less time on land except for basking. At times, they tend to spend weeks at sea in search of land and in some cases, barnacles have been observed growing on crocodile scales, indicative of the long periods they spend at sea.[76]

Despite their relative lethargy, saltwater crocodiles are agile predators and display surprising agility and speed when necessary, usually during strikes at prey. They are capable of explosive bursts of speed when launching an attack from the water. They can also swim at 15 to 18 mph (24 to 29 km/h) in short bursts, around three times as fast as the fastest human swimmers, but when cruising, they usually go at 2 to 3 mph (3.2 to 4.8 km/h). However, stories of crocodiles being faster than a race horse for short distances across land are little more than urban legend. At the water's edge, however, where they can combine propulsion from both feet and tail, their speed can be explosive.

While crocodilian brains are much smaller than those of mammals (as low as 0.05% of body weight in the saltwater crocodile), saltwater crocodiles are capable of learning difficult tasks with very little conditioning, learning to track the migratory route of their prey as the seasons change, and may possess a deeper communication ability than currently accepted.[77][78]

Hunting and diet

Like most species in the crocodilians family, saltwater crocodiles are not fastidious in their choice of food, and readily vary their prey selection according to availability, nor are they voracious, as they are able to survive on relatively little food for a prolonged period. Because of their size and distribution, saltwater crocodiles hunt the broadest range of prey species of any modern crocodilian.[8] The diet of hatchling, juvenile and subadult saltwater crocodiles has been subject to extensively greater scientific study than that of fully-grown crocodiles, in large part due to the aggression, territoriality and size of adults which make them difficult for biologists to handle without significant risk to safety, for both humans and the crocodiles themselves; the main method used for capturing adult saltwater crocodiles is a huge pole with large hooks meant for shark capture which restrict the crocodile's jaws but can cause damage to their snouts and even this is unproven to allow successful capture for crocodiles in excess of 4 m (13 ft 1 in). While for example 20th century biological studies rigorously cataloged the stomach contents of "sacrificed" adult Nile crocodiles in Africa,[79][80] few such studies were done on behalf of saltwater crocodiles despite the plethora that were slaughtered due to the leather trade during that time period. Therefore, the diet of adults is more likely to be based on reliable eye-witness accounts.[81][82][83] Hatchlings are restricted to feeding on smaller animals, such as small fish, frogs, insects and small aquatic invertebrates.[82] In addition to these prey, juveniles also take a variety of freshwater and saltwater fish, various amphibians, crustaceans, molluscs, such as large gastropods and cephalopods, birds, small to medium-sized mammals, and other reptiles, such as snakes and lizards. When crocodiles obtain a length of more than 1.2 m (3.9 ft), the significance of small invertebrate prey fades in favor of small vertebrates including fish and smaller mammals and birds.[84] The larger the animal grows, the greater the variety of its diet, although relatively small prey are taken throughout its lifetime.

Among crustacean prey, large mud crabs of the genus Scylla are frequently consumed, especially in mangrove habitats. Ground-living birds, such as the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) and different kinds of water birds, especially the magpie goose (Anseranas semipalmata), are the most commonly preyed upon birds, due to the increased chance of encounter.[85][86] Even swift-flying birds and bats may be snatched if close to the surface of water,[8] as well as wading birds while these are patrolling the shore looking for food, even down to the size of a common sandpiper (Actitis hypoleucos).[38][87] Mammalian prey of juveniles and subadults are usually as large as the smaller species of ungulates, such as the greater mouse-deer (Tragulus napu) and hog deer (Hyelaphus porcinus).[88] Various mammalian species including, monkeys (i.e. crab-eating macaques (Macaca fascicularis),[89] long-tailed macaques (M. fascicularis) & proboscis monkeys (Nasalis larvatus),[90]), gibbons, porcupines, wallabies,[91] mongoose, civets, jackals (Canis ssp.), turtles, flying foxes (Pteropus ssp.), hares (Lepus ssp.), rodents, badgers, otters,[92] fishing cats (Prionailurus viverrinus) and chevrotains are readily taken when encountered.[93] Unlike fish, crabs and aquatic creatures, mammals and birds are usually found only sporadically in or next to water so crocodiles seem to search for places where such prey may be concentrated, i.e. the water under a tree holding a flying fox colony or spots where herds of water buffaloes feed, in order to capture small animals disturbed by the buffalo or (if a large adult crocodile is hunting) weaker members of the buffalo herd.[86] Studies have shown that unlike freshwater crocodiles (which can easily be killed by toads), saltwater crocodiles are partially resistant to cane toad (Rhinella marina) toxins and can consume them but only in small quantities and not enough to provide effective natural control for this virulent introduced pest.[94] Large crocodiles, even the oldest males, do not ignore small species, especially those without developed escape abilities, when the opportunity arises. On the other hand, sub-adult saltwater crocodiles weighing only 8.7 to 15.8 kg (19 to 35 lb) (and measuring 1.36 to 1.79 m (4 ft 6 in to 5 ft 10 in)) have been recorded killing and eating goats (Capra aegagrus hircus) weighing 50 to 92% of their own body mass in Orissa, India, so are capable of attacking large prey from an early age.[93][95][96] It was found the diet of specimens in juvenile to subadult range, since they feed on any animals up to their own size practically no matter how small, was more diverse than adults who often ignored all prey below a certain size limit.[97]

Large animals taken by adult crocodiles include sambar deer (Rusa unicolor), wild boar (Sus scrofa), Malayan tapirs (Tapirus indicus), kangaroos, orangutans (Pongo ssp.), dingos (Canis lupus dingo), tigers (Panthera tigris),[98] and large bovines, such as banteng (Bos javanicus),[99] water buffalo (Bubalus arnee), and gaur (Bos gaurus).[72][100][101][102][103][104] However, larger animals are only sporadically taken due to the fact only large males typically attack very large prey and large ungulates and other sizeable wild mammals are only sparsely distributed in this species' range, outside of a few key areas such as the Sundarbans.[8] Off-setting this, goats, water buffalo and wild boar/pigs have been introduced to many of the areas occupied by saltwater crocodiles and returned to feral states to varying degrees and thus can amply support large crocodiles.[26] Any type of domestic livestock, such as chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus), sheep (Ovis aries), pigs, horses (Equus ferus caballus) and cattle (Bos primigenius taurus), and domesticated animals/pets may be eaten if given the opportunity.[8] As a seagoing species, the saltwater crocodile also preys on a variety of saltwater bony fish and other marine animals, including sea snakes, sea turtles, sea birds, dugongs (Dugong dugon), rays (including large sawfish[105]), and small sharks. Most witnessed acts of predation on marine animals have occurred in coastal waters or within sight of land, with female sea turtles and their babies caught during mating season when the turtles are closer to shore and bull sharks being the only largish shark with a strong propensity to patrol brackish and fresh waters.[8][35][106][107][108][109][110][111][112] However, there is evidence that saltwater crocodile do hunt while out in the open seas, based upon the remains of pelagic fishes that only dwell miles away from land being found in their stomachs.[5][6]

The hunting methods utilized by saltwater crocodiles are indistinct from any other crocodilian, with the hunting crocodile submerging and quietly swimming over to the prey before pouncing upwards striking suddenly. Unlike some other crocodilians, such as alligators and even Nile crocodiles, they are not known to have hunted on dry land.[8][26] Young saltwater crocodiles are capable of breaching their entire body into their air in a single upward motion while hunting prey that may be perched on low hanging branches.[82] While hunting rhesus macaques, crocodiles have been seen to knock the monkeys off a bank by knocking them with their tail, forcing the macaque into water for easy consumption. However, whether tail use in hunting is intentional or just an accidental benefit is not definitely clear.[26] As with other crocodilians, their sharp, peg-like teeth are well-suited to seize and tightly grip prey, but not designed to shear flesh. Small prey are simply swallowed whole, while larger animals are forcibly dragged into deep water and drowned or crushed.[113] Large prey is then torn into manageable pieces by "death rolling" (the spinning of the crocodile to twist off hunks of meat) or by sudden jerks of the head.[114] Occasionally, food items will be stored for later consumption once a crocodile eats its fill, although this can lead to scavenging by interlopers such as monitor lizards.[115]

Bite

_(8851846180).jpg)

Saltwater crocodiles hold the record for the highest bite force ever recorded in any animal, with a peak bite force of 16,414 N (3,690 lbf), far surpassing the highest recorded value in the spotted hyena of 4,500 N (1,012 lbf).[116] The extraordinary bite of crocodilians is a result of their anatomy. The space for the jaw muscle in the skull is very large, which is easily visible from the outside as a bulge at each side. The nature of the muscle is extremely stiff, almost as hard as bone to the touch, such that it can appear to be the continuum of the skull. Another trait is that most of the muscle in a crocodile's jaw is arranged for clamping down. Despite the strong muscles to close the jaw, crocodiles have extremely small and weak muscles to open the jaw. The jaws of a crocodile can be securely shut with several layers of duct tape.[117]

Reproduction

_juvenile_(8067785958).jpg)

%2C_Gembira_Loka_Zoo%2C_2015-03-15_01.jpg)

Saltwater crocodiles mate in the wet season, when water levels are at their highest. In Australia, the male and female engage in courtship in September and October, and the female lays eggs between November and March.[99] It is possible the rising temperatures of the wet season provoke reproductive behaviour in this species.[86] While crocodilians generally nest every year, there have been several recorded cases of female saltwater crocodiles nesting only every other year and also records of a female attempting to produce two broods in a single wet season.[86] The female selects the nesting site, and both parents will defend the nesting territory, which is typically a stretch of shore along tidal rivers or freshwater areas, especially swamps. Nests are often in surprisingly exposed location, often in mud with little to no vegetation around and thus limited protection from the sun and wind. The nest is a mound of mud and vegetation, usually measuring 175 cm (69 in) long and 53 cm (21 in) high, with an entrance averaging 160 cm (63 in) in diameter.[86] Some nests in unlikely habitats have occurred, such as rocky rubble or in a damp low-grass field.[118][119] The female crocodile usually scratches a layer of leaves and other debris around the nest entrance and this covering is reported to produce an "astonishing" amount of warmth for the eggs (conicidentially these nesting habits are similar to those of the birds known as megapodes that nest in upland areas of the same Australasian regions where saltwater crocodiles are found).[26][120] The female typically lays from 40 to 60 eggs, but some clutches have included up to 90. The eggs measure on average 8 by 5 cm (3.1 by 2.0 in) and weigh 113 g (4.0 oz) on average in Australia and 121 g (4.3 oz) in India.[99][121] These are relatively small, as the average female saltwater crocodile weighs around five times as much as a freshwater crocodile, but lays eggs that are only about 20% larger in measurement and 40% heavier than those of the smaller species.[38] The average weight of a new hatchling in Australia is reportedly 69.4 g (2.45 oz).[99] Although the female guards the nest for 80 to 98 days (in extreme high and low cases from 75 to 106 days), the loss of eggs is often high due to flooding and occasionally to predation.[99] As in all crocodilians, the sex of the hatchlings is determined by temperature. At 28–30 degrees all hatchlings will be female, at 30–32 degrees 86% of hatchlings are male, and at 33 or more degrees predominantly female (84%).[122] In Australia, goannas (Varanus giganteus) commonly eat freshwater crocodile eggs (feeding on up to 95% of clutch if discovered), but are relatively unlikely to eat saltwater crocodile eggs due to the vigilance of the imposing mother, with about 25% of the eggs being lost to goannas (less than half as many Nile crocodile eggs are estimated to be eaten by monitors in Africa).[38] A majority of the loss of eggs in the saltwater crocodile occurs due to flooding of the nest hole.[86][123]

As in all crocodilian species, the female saltwater crocodile exhibits a remarkable level of maternal care for a reptile. She excavates the nest in response to "yelping" calls from the hatchlings, and even gently rolls eggs in her mouth to assist hatching. The female will then carry the hatchlings to water in her mouth (as Nile crocodile and American alligator females have been observed doing when their eggs hatch) and remains with the young for several months. Despite her diligence, losses of baby crocodiles are heavy due to various predators and unrelated crocodiles of their own species. Only approximately 1% of the hatchlings will survive to adulthood.[124] By crocodilian standards, saltwater crocodile hatchlings are exceptionally aggressive to one another and will often fight almost immediately after being transported to water by their mother.[125] The young naturally start to disperse after around 8 months, and start to exhibit territorial behaviour at around 2.5-year-old. They are the most territorial of extant crocodilians and, due to their aggressiveness to conspecifics, from the dispersed immature stage on, they are never seen in concentrations or loose groups as are most other crocodilians.[126] However, even females will not reach proper sexual maturity for another 10 years. Saltwater crocodiles that survive to adulthood can attain a very long lifespan, with an estimated life expectancy upwards of 70 years, and some individuals possibly exceed 100 years, although no such extreme ages have been verified for any crocodilian.[37][127] While adults have few predators, baby saltwater crocodiles may fall prey to monitor lizards (occasionally but not commonly the numerous goanna in Australia and the Asian water monitor (Varanus salvator) further north), predatory fish (especially the barramundi (Lates calcarifer)), wild boars, rats, various aquatic and raptorial birds (e.g. black-necked storks (Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus) and white-bellied sea eagles (Haliaeetus leucogaster)), pythons, larger crocodiles, and many other predators.[86][99][121][123] Pigs and cattle also occasionally inadvertently trample eggs and nests on occasion and degrade habitat quality where found in numbers.[128] Juveniles may also fall prey to tigers and leopards (Panthera pardus) in certain parts of their range, although encounters between these predators are rare and cats are likely to avoid areas with saltwater crocodiles.[129]

Conservation status

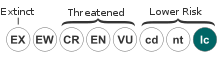

In addition to being hunted for its meat and eggs, the saltwater crocodile has the most commercially valuable skin of any crocodilian; and unregulated hunting during the 20th century caused a dramatic decline in the species throughout its range, with the population in northern Australia reduced 95% by 1971. The years from 1940 to 1970 were the peak of unregulated hunting and may have regionally caused irreparable damage to saltwater crocodile populations.[59] The species currently has full legal protection in all Australian states and territories where it is found – Western Australia (since 1970), Northern Territory (since 1971) and Queensland (since 1974).[130] Illegal hunting still persists in some areas, with protection in some countries being grossly ineffective, and trade is often difficult to monitor and control over such a vast range. Despite this, the species has made a dramatic recovery in recent decades. Because of its resurgence, the species is considered of minimal concern for extinction. However, many areas have not recovered, some population surveys have shown that although young crocodiles are present, fewer than 10% of specimens spotted are in adult size range and no particularly large males, such as Sri Lanka or the Republic of Palau. This is indicative of both potential continued persecution and exploitation and a non-recovered breeding population.[131][132] In a more balanced population, such as those from Bhitarkanika National Park or Sabah, Malaysia, 28% and 24.2% of specimens observed were in the adult size range of more than 3 m (9 ft 10 in).[66][133]

Currently, the species is listed in CITES as follows:

- Appendix I (prohibiting all commercial trade in the species or its byproducts): All wild populations except for those of Australia, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea

- Appendix II (commercial trade allowed with export permit; import permits may or may not be required depending on the laws of the importing country): Australia, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea wild populations, plus all worldwide populations bred in captivity for commercial purposes

Habitat loss continues to be a major problem. In northern Australia, much of the nesting habitat of the saltwater crocodile is susceptible to trampling by feral water buffalo, although buffalo eradication programs have now reduced this problem considerably. Even where large areas of suitable habitat remain, subtle habitat alterations can be a problem, such as in the Andaman Islands, where freshwater areas, used for nesting, are being increasingly converted to human agriculture. After the commercial value of crocodile skins waned, perhaps the greatest immediate challenge to implementing conservation efforts has been the occasional danger the species can be to humans and the resulting negative view of the crocodile.[124][134]

Relationship with humans

Attacks on humans

Of all the crocodilians, the saltwater crocodile has the strongest tendency to treat humans as prey, and has a long history of attacking humans who unknowingly stray into its territory. As a result of its power, intimidating size and speed, survival of a direct predatory attack is unlikely if the crocodile is able to make direct contact. By contrast to the American policy of encouraging a certain degree of habitat coexistence with alligators, the only recommended policy for dealing with saltwater crocodiles is to completely avoid their habitat whenever possible, as they are exceedingly aggressive when encroached upon.[26]

Exact data on attacks are limited outside Australia, where one or two fatal attacks are reported per year.[136] From 1971 to 2013, the total number of fatalities reported in Australia due to saltwater crocodile attack was 106.[137][138] The low level of attacks may be due to extensive efforts by wildlife officials in Australia to post crocodile warning signs at numerous at-risk billabongs, rivers, lakes and beaches.[139] Also, recent, less-publicised attacks have been reported in Borneo,[140] Sumatra,[141] Eastern India (Andaman Islands),[142][143] and Burma.[144] In Sarawak, Borneo, the average number of fatal attacks is reportedly 2.8 annually for the years from 2000 to 2003.[145] In the Northern Territory in Australia, attempts have made to relocate saltwater crocodiles who've displayed aggressive behaviour towards humans but these have proven ineffective as the problem crocodiles are apparently able to find their way back towards their original territories.[146] In the Darwin area from 2007–2009, 67–78% of "problem crocodiles" were identified as males.[147]

Many attacks in areas outside Australia are believed to go unreported, with one study positing up to 20 to 30 attacks occur every year.[145] This number may be conservative in light of several areas where humans and saltwater crocodiles co-exist in relatively undeveloped, low-economy and rural regions, where attacks are likely to go unreported.[148] However, claims in the past that saltwater crocodiles are responsible for thousands of human fatalities annually are likely to have been exaggerations and were probably falsified to benefit leather companies, hunting organizations and other sources which may have benefited from maximizing the negative perception of crocodiles for financial gain.[26][35][145] Although it does not pay to underestimate such a formidable predator, one that has no reason to not view humans as prey, many wild saltwater crocodiles are normally quite wary of humans and will go out of their way to submerge and swim away from them, even in large adult males, if previously subject to harassment or persecution.[149][150] Some attacks on humans appear to be territorial rather than predatory in nature, with crocodiles over two years in age often attacking anything that comes into their area (including boats). Humans can usually escape alive from such encounters, which comprise about half of all attacks. Non-fatal attacks usually involve crocodiles of 3 m (9 ft 10 in) or less in length. Fatal attacks, more likely to be predatory in motivation, commonly involve larger crocodiles with an average estimated size of 4.3 m (14 ft 1 in). Under normal circumstances, Nile crocodiles are believed to be responsible for a considerably greater number of fatal attacks on humans than saltwater crocodiles, but this may have more to do with the fact that many people in Africa tend to rely on riparian areas for their livelihood, which is less prevalent in most of Asia and certainly less so in Australia.[145] In the Andaman Islands, the number of fatal attacks on humans has reportedly increased, the reason inferred due to habitat destruction and reduction of natural prey.[151]

During the Japanese retreat in the Battle of Ramree Island on 19 February 1945, saltwater crocodiles may have been responsible for the deaths of over 400 Japanese soldiers. British soldiers encircled the swampland through which the Japanese were retreating, condemning the Japanese to a night in the mangroves, which were home to thousands of saltwater crocodiles. Many Japanese soldiers did not survive this night, but their death mainly as a result of crocodile attacks has been doubted.[152] Another reported mass attack reportedly involve a cruise in eastern India where a boat accident forced 28 people into the water where they were reportedly consumed by saltwater crocodiles.[35] Another notorious crocodile attack was in 1985, on ecofeminist Val Plumwood, who survived the attack.[153][154]

Cultural references

According to Wondjina, the mythology of Indigenous Australians, the saltwater crocodile was banished from the fresh water for becoming full of bad spirits and growing too large, unlike the freshwater crocodile, which was somewhat revered.[155] As such, Aboriginal rock art depicting the saltwater crocodile is rare, although examples of up to 3,000 years old can be found in caves in Kakadu and Arnhem land, roughly matching the species distribution. The species is frequently depicted in contemporary aboriginal art.[156]

The species is featured on several postage stamps, including an 1894 State of North Borneo 12-cent stamp; a 1948 Australian 2 shilling stamp depicting an aboriginal rock artwork of the species; a 1966 Republic of Indonesia stamp; a 1994 Palau 20-cent stamp; a 1997 Australian 22-cent stamp; and a 2005 1 Malaysian ringgit postage stamp.

The species has featured in contemporary Australian film and television including the "Crocodile" Dundee series of films and The Crocodile Hunter television series. There are now several saltwater crocodile-themed parks in Australia.

The crocodile is considered to be holy on Timor. According to legend, the island was formed by a giant crocodile. The Papuan people have a similar and very involved myth and traditionally the crocodile was described as relative (normally a father or grandfather).[26]

Examples of large unconfirmed saltwater crocodiles

Large saltwater crocodiles have always attracted mainstream attention throughout the ages, and have suffered from all sorts of big fish stories and hunter tales, due to man's desire to find the largest of an any given thing. Therefore, the largest size recorded for a saltwater crocodile has always been a subject of considerable controversy. The reason behind unverified sizes is either the case of insufficient/inconclusive data or exaggeration from a folkloric point of view. This section is dedicated to examples of the largest saltwater crocodiles recorded outside scientific norms measurement and estimation, with the aim of satisfying the public interest without creating data pollution, as well as serving an educational purpose of guiding the reader to separate fact from possible fiction. Below, in descending order starting from the largest, are some examples of large unconfirmed saltwater crocodiles, recorded throughout history.

- A crocodile shot in the Bay of Bengal in 1840 was reported at 10.1 m (33 ft 2 in). Furthermore, this specimen was claimed to have a belly girth of 4.17 m (13 ft 8 in) and a body mass estimated 3,000 kg (6,600 lb). However, the skull of this specimen was examined by Guinness Records and found to be only 66.5 cm (26.2 in) in length, indicating the above size was considerably exaggerated and the animal would have probably measured no more than 5.89 m (19 ft 4 in).[35]

- James R. Montgomery, who ran a plantation near to the Lower Kinabatangan Segama Wetlands in Borneo from 1926 to 1932, claimed to have netted, killed, and examined numerous crocodiles well over 6.1 m (20 ft 0 in) there, including a specimen he claims measured 10 m (32 ft 10 in). However, no one scientifically confirmed any of Montgomery's specimens and no voucher specimens are known.[35]

- A crocodile shot in Queensland in 1957, nicknamed Krys the croc (named after the woman that shot the crocodile in July 1957; Krystina Pawlowski), was reported to be 8.63 m (28 ft 4 in) long, but no verified measurements were made and no remains of this crocodile exist.[157][158] A "replica" of this crocodile has been made as a tourist attraction.[159][160][161]

- A crocodile killed in 1823 at Jalajala on the main island of Luzon in the Philippines was reported at 8.2 m (26 ft 11 in). However the skull of the specimen is 66.5 cm (26.2 in) long indicating an animal of approximately 6.1 m (20 ft 0 in).[35]

- The skull of a crocodile shot in Odisha, India,[162] was claimed to measure 7.6 m (24 ft 11 in) in life, but when given scholarly examination, was thought to have come from a crocodile of a length no greater than 7 m (23 ft 0 in).[163]

- A reported 7.6 m (24 ft 11 in) crocodile was killed in the Hooghly River in the Alipore District of Calcutta. However, examinations of the animal's skull, one of the largest skulls known to exist for the species at 75 cm (30 in) long, actually indicating it could have measured 6.7 m (22 ft 0 in).[35]

- In 2006, Guinness accepted a 7.1 m (23 ft 4 in), 2,000-kg (4,400-lb) male saltwater crocodile living within Bhitarkanika Park in Odisha. Due to the difficulty of trapping and measuring a very large living crocodile, the accuracy of these dimensions are yet to be verified. These observations and estimations have been made by park officials over the course of ten years, from 2006 to 2016, however, regardless of the skill of the observers it cannot be compared to a verified tape measurement, especially considering the uncertainty inherent in visual size estimation in the wild.[164] In addition, this region may contain up to four other specimens measuring over 6.1 m (20 ft 0 in).[162][165]

- S. Baker (1874) claimed that in Sri Lanka in the 1800s, specimens measuring 6.7 m (22 ft 0 in) or more were commonplace.[35] However, the largest specimen killed on the island that was considered authentic by Guinness Records was a suspected man-eater killed in the Eastern Province that measured exactly 6 m (19 ft 8 in) in length.[35]

- In May 1966 Herb Schweighofer shot an individual along the northeastern coast of Papua New Guinea said to measure 6.32 m (20 ft 9 in) long with a belly girth of 2.74 m (9 ft 0 in).[35]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Crocodile Specialist Group (1996). "Crocodylus porosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ↑ Allen, G. R. (1974). "The marine crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, from Ponape, Eastern Caroline Islands, with notes on food habits of crocodiles from the Palau Archipelago". Copeia. 1974 (2): 553–553. doi:10.2307/1442558. JSTOR 1442558.

- 1 2 3 Britton, Adam R. C.; Whitaker, Romulus; Whitaker, Nikhil (2012). "Here be a Dragon: Exceptional Size in Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) from the Philippines". Herpetological Review. 43 (4).

- 1 2 "Crocodylus porosus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2015-06-03.

- 1 2 Callaway, J. M., & Nicholls, E. L. (Eds.). (1997). Ancient marine reptiles. Academic Press.

- 1 2 Blaber, S. J. (2008). Tropical estuarine fishes: ecology, exploration and conservation. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ "Saltwater Crocodile facts". Aquaticcommunity.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

In Australia, one or two fatal attacks are reported on average per year.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ross, Charles A; Garnett, Stephen, eds. (1989). Crocodiles and Alligators. Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816021741.

- ↑ Thomas, Abbie; Willis, Paul (July–September 2006). "The Dinosaur Musterers – Dawn of a crocodilian dynasty". Australian Geographic (83): 52–53. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Missing link crocodile found down under". Science Buzz. Science Museum of Minnesota. 18 June 2006. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "Ancestor of all modern crocodilians discovered in outback Queensland". The University of Queensland. 14 June 2006. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ Li, Yan; Wu, Xiaobing; Ji, Xuefeng; Yan, Peng & Amato, George (2007). "The complete mitochondrial genome of salt-water crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) and phylogeny of crocodilians". Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 34 (2): 119–128. doi:10.1016/S1673-8527(07)60013-7. PMID 17469784.

- ↑ Johnson, David (4 November 2009). The Geology of Australia. Cambridge University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-521-76741-5. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- 1 2 Oaks, J. R. (2011). "A time-calibrated species tree of Crocodylia reveals a recent radiation of the true crocodiles" (PDF). Evolution. 65 (11): 3285–3297. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01373.x. PMID 22023592.

- ↑ Willis, P. M. A. (1997). "Review of fossil crocodilians from Australasia". Aust. J. Zool. 30 (3): 287–298. doi:10.7882/AZ.1997.004.

- ↑ Molnar R. E. (1979). "Crocodylus porosus from the Pliocene Allingham formation of North Queensland. Results of the Ray E. Lemley expeditions, part 5". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 19: 357–365.

- ↑ Brochu, C. A. (2000). "Congruence between physiology, phylogenetics and the fossil record on crocodylian historical biogeography", pp. 9–28 in Grigg, G. C., Seebacher, F. & Franklin, C. E. (eds.) Crocodilian Biology and Evolution. Surry Beatty & Sons (Chipping Norton, Aus.), .

- ↑ Man, Z.; Yishu, W.; Peng, Y.; Wu, X. (2011). "Crocodilian phylogeny inferred from twelve mitochondrial protein-coding genes, with new complete mitochondrial genomic sequences for Crocodylus acutus and Crocodylus novaeguineae". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 60 (1): 62–67. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.03.029. PMID 21463698.

- 1 2 3 Naish, D. "The Saltwater Crocodile, and all that it implies (crocodiles part III)". Scientific American- Tetrapod Zoology. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- 1 2 Brazaitis, P. (2001). A Guide to the Identification of the Living Species of Crocodilians. Wildlife Conservation Society.

- ↑ Ross, C.A. (1990). "Crocodylus raninus S. Müller and Schlegel, a valid species of crocodile (Reptilia: Crocodylidae) from Borneo". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 103: 955–961.

- ↑ Ross, C.A. (1992). "Designation of a lectotype for Crocodylus raninus S. Müller and Schlegel (Reptilia: Crocodylidae), the Borneo crocodile". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 105: 400–402.

- ↑ Wells, R.W. & Wellington, C.R. (1985). "A classification of the Amphibia and Reptilia of Australia". Australian Journal of Herpetology. Suppl. Ser. 1: 1–61.

- ↑ Das, I.; Charles, J. K. (2000). "A Record of Crocodylus raninus Müller & Schlegel, 1844 from Brunei, North-western Borneo". Sabah Parks Nature Journal. 3: 1–5.

- ↑ Brochu, C. A. (2009). Phylogenetic relationships and divergence timing of Crocodylus based on morphology and the fossil record.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Guggisberg, C.A.W. (1972). Crocodiles: Their Natural History, Folklore, and Conservation. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 195. ISBN 0-7153-5272-5.

- ↑ Kondo, H. (1970). Grolier's Amazing World of Reptiles. New York, NY: Grolier Interprises Inc.

- ↑ Ross, F. D. & Mayer, G. C. 1983. On the dorsal armor of the Crocodilia. In Rhodin, A. G. J. & Miyata, K. (eds) Advances in Herpetology and Evolutionary Biology. Museum of Comparative Zoology (Cambridge, Mass.), pp. 306–331.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Britton, Adam. "Crocodylus porosus (Schneider, 1801)". The Crocodilian Species List. Archived from the original on 8 January 2006.

- ↑ Greer, Allen E. (1974). "On the Maximum Total Length of the Salt-Water Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus)". Journal of Herpetology. 8 (4): 381–384. doi:10.2307/1562913. JSTOR 1562913.

- ↑ Naish, Darren (30 October 2008). "The world's largest modern crocodilian skull – Tetrapod Zoology". Scienceblogs.com. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Whitaker R.; Whitaker N. (2008). "Who's got the biggest?". Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter. 27 (4): 26–30.

- ↑ "Australian crocodile Elvis sinks teeth into lawnmower". CNN.com. 28 December 2011.

- ↑ "Australian Saltwater Crocodile (Estuarine Crocodile) – Crocodylus porosus". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ↑ Lanworn, R. (1972). The Book of Reptiles. New York, NY: The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. ISBN 0600312739.

- 1 2 3 "Crocodylus porosus". Kingsnake.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Insights into Crocodile Lifestyles" (PDF). newholland.com.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2009.

- ↑ "World's Biggest Crocodiles". Madras Croc Bank Trust. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- ↑ Olsson, A.; Phalen, D. (2012). "Preliminary studies of chemical immobilization of captive juvenile estuarine (Crocodylus porosus) and Australian freshwater (C. johnstoni) crocodiles with medetomidine and reversal with atipamezole". Veterinary anaesthesia and analgesia. 39 (4): 345–356. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2995.2012.00721.x. PMID 22642399.

- 1 2 Webb, G., & Manolis, S. C. (1989). Crocodiles of Australia. Reed Books.

- ↑ Webb, G. J. W.; Messel, H.; Crawford, J.; Yerbury, M. J. (1978). "Growth Rates of Crocodylus porosus (Reptilia: Crocodilia) From Arnhem Land, Northern Australia". Wildlife Research. 5 (3): 385–399. doi:10.1071/WR9780385.

- ↑ Greer, A. E. (1974). "On the maximum total length of the salt-water crocodile (Crocodylus porosus)". Journal of Herpetology. 8 (4): 381–384. doi:10.2307/1562913. JSTOR 1562913.

- ↑ Whitaker, Romulus; Whitaker, Nikhil (2008). "Who's Got the Biggest?". Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter. 27 (4).

- ↑ Grigg, G.; Gans, C. "Morphology & Physiology of Crocodylia" (PDF). Australian Government- Department of the Environment. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ↑ Kay, W. R. (2005). "Movements and home ranges of radio-tracked Crocodylus porosus in the Cambridge Gulf region of Western Australia". Wildlife Research. 31 (5): 495–508. doi:10.1071/WR04037.

- ↑ Campbell, H. A.; Dwyer, R. G.; Irwin, T. R.; Franklin, C. E. (2013). "Home range utilisation and long-range movement of estuarine crocodiles during the breeding and nesting season". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e62127. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062127. PMC 3641080

. PMID 23650510.

. PMID 23650510. - ↑ Mercado V. P. (2008). "Current status of the crocodile industry in the Republic of the Philippines". National Museum Papers. 14: 26–34.

- ↑ Brazaitis, P. (1987). Identification of crocodilian skins. Pty Lim., Chipping Norton, Australia.

- ↑ Hiremath, K. G. (2003). Recent advances in environmental science. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 81-7141-679-9.

- ↑ de Vos, A. (1984). "Crocodile conservation in India" (PDF). Biological conservation. 29 (2): 183–189. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(84)90076-4.

- ↑ Choudhury, B.C. & de Silva, A. (2013). Crocodylus palustris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T5667A3046723.en

- ↑ Choudhury, B.C., Singh, L.A.K., Rao, R.J., Basu, D., Sharma, R.K., Hussain, S.A., Andrews, H.V., Whitaker, N., Whitaker, R., Lenin, J., Maskey, T., Cadi, A., Rashid, S.M.A., Choudhury, A.A., Dahal, B., Win Ko Ko, U., Thorbjarnarson, J & Ross, J.P. (2007). Gavialis gangeticus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

- ↑ Messel, H.; Vorlicek, G. C. (1986). "Population-Dynamics and Status of Crocodylus-Porosus in the Tidal Waterways of Northern Australia". Wildlife Research. 13 (1): 71–111. doi:10.1071/WR9860071.

- ↑ Crocodile Specialist Group. (1996). Crocodylus johnsoni. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T46589A11063442.en

- ↑ "West Alligator River". Northern Territory Land Information System. Northern Territory Government. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Jelden, D. C. (1980). "Preliminary Studies on the Breeding Biology of Crocodylus porosus and Crocodylus n. novaguineae on the Middle Sepik (Papua New Guinea)". Amphibia-Reptilia. 1 (3): 353–358. doi:10.1163/156853881X00456.

- ↑ Humphrey, S. R., & Bain, J. R. (1990). Endangered animals of Thailand (No. 6). Sandhill Crane Press.

- 1 2 Whitaker, R. (1982). "Status of Asian crocodilians", p. 237 in Crocodiles: Proceedings of the 5th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Convened at the Florida State Museum, Gainesville, Florida, USA, 12 to 16 August 1980. IUCN.

- ↑ Stuart, B. L.; Hayes, B.; Manh, B. H.; Platt, S. G. (2002). "Status of crocodiles in the U Minh Thuong Nature Reserve, southern Vietnam". Pacific Conservation Biology. 8 (1): 62. doi:10.1071/PC020062.

- ↑ Platt, S. G.; Holloway, R. H. P.; Evans, P. T.; Paudyal, K.; Piron, H.; Rainwater, T. R. (2006). "Evidence for the historic occurrence of Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801 in Tonle Sap, Cambodia". Hamadryad-Madras. 30 (1/2): 206.

- ↑ "Crocodile kills man in wildlife sanctuary – World news – World environment – msnbc.com". MSNBC. 20 April 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ↑ Thorbjarnarson, J.; Platt, S. G.; Khaing, U. (2000). "A population survey of the estuarine crocodile in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar". Oryx. 34 (4): 317–324. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3008.2000.00135.x.

- ↑ Webb, G. J. (2000). "Risk of extinction and categories of endangerment: perspectives from long-lived reptiles". Population ecology. 42 (1): 11–17. doi:10.1007/s101440050004.

- ↑ "Current Distribution of Crocodylus porosus". Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- 1 2 Stuebing, R. B.; Ismail, G.; Ching, L. H. (1994). "The distribution and abundance of the Indo-Pacific crocodile Crocodylus porosus Schneider in the Klias River, Sabah, east Malaysia". Biological conservation. 69 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(94)90322-0.

- ↑ Klock, J. (2008). Historic Hydrologic Landscape Modification and Human Adaptation in Central Lombok, Indonesia from 1894 to the Present.

- ↑ Bezuijen, M.R., Shwedick, B., Simpson, B.K., Staniewicz, A. & Stuebing, R. (2014). Tomistoma schlegelii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T21981A2780499.en

- ↑ Bezuijen, M., Simpson, B., Behler, N., Daltry, J. & Tempsiripong, Y. (2012). Crocodylus siamensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012.RLTS.T5671A3048087.en

- 1 2 https://ecolumn.net/iriewani.htm

- ↑ 西表島浦内川河口域の生物多様性と伝統的自然資源利用の綜合調査報告書1

- 1 2 Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Zaidi, Y. F.; Kanaujia, A. (2012). A review on status and conservation of salt water crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) in India (PDF). pp. 141–148.

- ↑ Schmidt-Nielsen, K. (1997). Animal physiology: adaptation and environment. Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Moskvitch, Katia (7 June 2010). "BBC News – Crocodiles 'surf' long distance on ocean currents". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Grigg, G. C.; Seebacherd, F.; Beard, L. A.; Morris, D. (1998). "Thermal relations of large crocodiles, Crocodylus porosus, free-ranging in a naturalistic situation". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 265 (1407): 1793–1799. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0504. PMC 1689355

.

. - ↑ "Lepas anatifera Linnaeus, 1758". WallaWalla. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ "Big Gecko – Crocodile Management, Research and Filming". Crocodilian.com. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "Crocodile Communication: Crocodiles, Caimans, Alligators, Gharials". Flmnh.ufl.edu. 5 March 1996. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Cott, H.B. (1961). "Scientific results of an inquiry into the ecology and economic status of the Nile crocodile (Crocodilus niloticus) in Uganda and Northern Rhodesia". The transactions of the Zoological Society of London. 29 (4): 211–356. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1961.tb00220.x.

- ↑ Graham, A., & Beard, P. (1973). Eyelids of Mornings. A. & W. Visual Library, Greenwich, CT, 113.

- ↑ Webb, G. J.; Hollis, G. J.; Manolis, S. C. (1991). "Feeding, growth, and food conversion rates of wild juvenile saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus)". Journal of Herpetology. 25 (4): 462–473. doi:10.2307/1564770. JSTOR 1564770.

- 1 2 3 Davenport, J.; Grove, D. J.; Cannon, J.; Ellis, T. R.; Stables, R. (1990). "Food capture, appetite, digestion rate and efficiency in hatchling and juvenile Crocodylus porosus". Journal of Zoology. 220 (4): 569–592. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1990.tb04736.x.

- ↑ Webb, G. J.; Messel, H. (1977). "Crocodile capture techniques". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 41 (3): 572–575. doi:10.2307/3800531. JSTOR 3800531.

- ↑ Taylor, J. A. (1979). "The foods and feeding habits of subadult Crocodylus porosus Schneider in northern Australia". Wildlife Research. 6 (3): 347–359. doi:10.1071/WR9790347.

- ↑ "Emu (Dromaius Novaehollandiae) – Animals – A–Z Animals – Animal Facts, Information, Pictures, Videos, Resources and Links". A–Z Animals. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Messel, H., & Vorlicek, G. C. (1989). "Ecology of Crocodylus porosus in northern Australia", pp. 164–183 in Crocodiles: Their Ecology, Management and Conservation. IUCN. ISBN 2880329876

- ↑ Yalden, D.; T. Dougall (2004). "Production, Survival, and Catchability of Chicks of Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos". Wader Study Group Bulletin. 104: 82–84.

- ↑ Cramb, R. A.; Sujang, P. S. (2013). "The mouse deer and the crocodile: oil palm smallholders and livelihood strategies in Sarawak, Malaysia". The Journal of Peasant Studies. 40 (1): 129–154. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.750241.

- ↑ Galdikas, B. M.; Yeager, C. P. (1984). "Brief report: Crocodile predation on a crab-eating macaque in Borneo". American Journal of Primatology. 6 (1): 49–51. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350060106.

- ↑ Otani, Y., ustine Tuugaz, A., Bernard, H., Matsuda, I., & Kinabalu, K. Opportunistic predation and predation-related events on long-tailed macaque and proboscis monkey in Kinabatangan, Sabah, Malaysia.

- ↑ Blumstein, D. T.; Daniel, J. C.; Sims, R. A. (2003). "Group size but not distance to cover influences agile wallaby (Macropus agilis) time allocation". Journal of Mammalogy. 84 (1): 197–204. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2003)084<0197:GSBNDT>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Kruuk, H. 1995. Wild Otters. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Corlett, R. T. (2011). "Vertebrate carnivores and predation in the Oriental (Indomalayan) region". Raffles Bull. Zool. 59: 325–360.

- ↑ Letnic, M.; Webb, J. K.; Shine, R. (2008). "Invasive cane toads (Bufo marinus) cause mass mortality of freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnstoni) in tropical Australia". Biological Conservation. 141 (7): 1773–1782. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.04.031.

- ↑ Kar, S. K.; Bustard, H. R. (1983). "Saltwater crocodile attacks on man". Biological Conservation. 25 (4): 377–382. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(83)90071-X.

- ↑ Kar, S. K.; Bustard, H. R. (1983). "Attacks on domestic livestock by juvenile saltwater crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, in Bhitarkanika Wildlife Sanctuary, Orissa India". Amphibia-Reptilia. 4 (1): 81–83. doi:10.1163/156853883X00283.

- ↑ Hanson, J. O.; Salisbury, S. W.; Campbell, H. A.; Dwyer, R. G.; Jardine T. D.; Franklin, C. E. (2015). "Feeding across the food web: The interaction between diet, movement and body size in estuarine crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus)". Austral Ecology. 40 (3): 275–286. doi:10.1111/aec.12212.

- ↑ Dean Nelson. "Fifteen-foot Bengali crocodile claims king of jungle title from tiger". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Leach, G., Delaney, R., & Fukuda, Y. (2009). Management program for the saltwater crocodile in the Northern Territory of Australia, 2009–2014. Department of Natural Resources, Environment, the Arts and Sport.

- ↑ Collins, B. (2005). "Crocodiles Inside Out: A Guide to the Crocodilians and Their Functional Morphology". Australian Ecology. 30 (4): 487–508. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2005.01448.x.

- ↑ Russon, A. E.; Kuncoro, P.; Ferisa, A.; Handayani, D. P. (2010). "How orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) innovate for water". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 124 (1): 14–28. doi:10.1037/a0017929. PMID 20175593.

- ↑ NG, M. & Mendyk, R. W. (2012). "Predation of an Adult Malaysian Water monitor Varanus salvator macromaculatus by an Estuarine Crocodile Crocodylus porosus". Biawak. 6 (1): 34–38.

- ↑ Butler, J. R.; Linnell, J. D.; Morrant, D.; Athreya, V.; Lescureux, N.; McKeown, A. (2013). "Dog eat dog, cat eat dog: social-ecological dimensions of dog predation by wild carnivores". Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation. Oxford University Press. p. 117.

- ↑ De Silva, M.; Dissanayake, S.; Santiapillai, C. (1994). "Aspects of the population dynamics of the wild Asiatic water buffalo(Bubalus bubalis) in Ruhuna National Park, Sri Lanka" (PDF). Journal of South Asian Natural History. 1 (1): 65–76.

- ↑ "FLMNH Ichthyology Department: Green Sawfish". www.flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- ↑ Walker, Pam; Wood, Elaine (2009-01-01). The Saltwater Wetland. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438122359.

- ↑ "Significant Trade in Wildlife: a review of selected species in CITES Appendix II. Volume 2: reptiles and invertebrates : Luxmoore, R., Groombridge, B., Broad, S., IUCN Conservation Monitoring Centre : Free Download & Streaming". Internet Archive. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- ↑ Reid, Robert (2011-03-01). Shark!: Killer Tales from the Dangerous Depths: Killer Tales from the Dangerous Depths (Large Print 16pt). ReadHowYouWant.com. ISBN 9781459613287.

- ↑ "World Building June: Day 4". the-tabularium.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- ↑ "Crocodile vs. shark photos". photos1.blogger.com.

- ↑ "No Bull: Saltwater Crocodile Eats Shark". UnderwaterTimes.com. 13 August 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ Whiting, S. D.; Whiting, A. U. (2011). "Predation by the Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) on sea turtle adults, eggs, and hatchlings". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 10 (2): 198–205. doi:10.2744/CCB-0881.1.

- ↑ "Crocodiles Have Strongest Bite Ever Measured, Hands-on Tests Show". News.nationalgeographic.com. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Saltwater Crocodiles, Crocodylus porosus ~". Marinebio.org. 14 January 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Doody, J. S. (2009). "Eyes bigger than stomach: prey caching and retrieval in the saltwater crocodile, Crocodylus porosus". Herpetological Review. 40 (1): 26.

- ↑ Erickson, GM; Gignac PM; Steppan SJ; Lappin AK; Vliet KA; et al. (2012). "Insights into the Ecology and Evolutionary Success of Crocodilians Revealed through Bite-Force and Tooth-Pressure Experimentation". PLoS ONE. 7 (3): e31781. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031781. PMC 3303775

. PMID 22431965.

. PMID 22431965. - ↑ Cogger, H.G. (1996). Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia. Chatswood, NSW: Reed Books.

- ↑ Somaweera, R.; Shine, R. (2013). "Nest-site selection by crocodiles at a rocky site in the Australian tropics: Making the best of a bad lot". Austral Ecology. 38 (3): 313–325. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2012.02406.x.

- ↑ Magnusson, W. E. (1980). "Habitat required for nesting by Crocodylus porosus (Reptilia: Crocodilidae) in northern Australia". Aust. Wildl. Res. 7 (1): 149–156. doi:10.1071/WR9800149.

- ↑ Seymour, R. S.; Ackerman, R. A. (1980). "Adaptations to underground nesting in birds and reptiles". American Zoologist. 20 (2): 437–447. doi:10.1093/icb/20.2.437.

- 1 2 Gopi, G.V.; ANGOM, S. (2007). "Aspects of nesting biology of Crocodylus porosus at Bhitarkanika, Orissa, Eastern India". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 104 (3): 328–333.

- ↑ Lang, J. W.; Andrews, H. V. (1994). "Temperature-dependent sex determination in crocodilians". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 270 (1): 28–44. doi:10.1002/jez.1402700105.

- 1 2 Magnusson, W. E. (1982). "Mortality of eggs of the crocodile Crocodylus porosus in northern Australia". Journal of Herpetology. 16 (2): 121–130. doi:10.2307/1563804. JSTOR 1563804.

- 1 2 "Crocodilian Species – Australian Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus)". Flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ↑ Brien, M. L.; Webb, G. J.; Lang, J. W.; McGuinness, K. A.; Christian, K. A. (2013). "Born to be bad: agonistic behaviour in hatchling saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus)". Behaviour. 150 (7): 737–762. doi:10.1163/1568539x-00003078.

- ↑ Lang, J. W. (1987). "Crocodilian behaviour: implications for management", pp. 273–294 in Wildlife management: crocodiles and alligators.

- ↑ "UNEP-WCMC – Estuarine Crocodile". Web.archive.org. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Webb, G. J. W.; Manolis, S. C.; Buckworth, R.; Sack, G. C. (1983). "An examination of Crocodylus porosus nests in two northern Australian freshwater swamps, with an analysis of embryo mortality". Wildlife Research. 10 (3): 571–605. doi:10.1071/WR9830571.

- ↑ Somaweera, R.; Brien, M.; Shine, R. (2013). "The role of predation in shaping crocodilian natural history". Herpetological Monographs. 27 (1): 23–51. doi:10.1655/HERPMONOGRAPHS-D-11-00001.

- ↑ "Crocodylus porosus – Salt-water Crocodile, Estuarine Crocodile". Environment.gov.au. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ↑ Gramantez, D. (2008) A case study of the Saltwater Crocodile Crocodylus porosus in Muthurajawela Marsh, Sri Lanka – Considerations for conservation. IUCN- Crocodile Specialist Group.

- ↑ Brazaitis, P.; Eberdong, J.; Brazaitis, P. J.; Watkins-Colwell, G. J. (2009). "Notes on the saltwater crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, in the Republic of Palau". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 50 (1): 27–48. doi:10.3374/014.050.0103.

- ↑ Kar, S. K. (1992). "Conservation, research, and management of estuarine crocodiles Crocodylus porosus, respectively, of the crocodiles detected were Schneider in Bhitarkania Wildlife Sanctuary, Orissa: India during the last 17 years", pp. 222–242 in Crocodiles. Proceedings of the 11th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group .

- ↑ Tisdell, C.; Nantha, H. S.; Wilson, C. (2007). "Endangerment and likeability of wildlife species: How important are they for payments proposed for conservation?". Ecological Economics. 60 (3): 627–633. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.01.007.

- ↑ "Crocodile Management" (PDF). Northern Territory Government. Retrieved 2016-05-06.

- ↑ Caldicott, David G.E. (September 2005). "Crocodile Attack in Australia: An Analysis of Its Incidence and Review of the Pathology and Management of Crocodilian Attacks in General". Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 16 (3): 143–159. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(2005)16[143:CAIAAA]2.0.CO;2. PMID 16209470.

- ↑ Manolis, S. C., & Webb, G. J. (2013, September). "Assessment of saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) attacks in Australia (1971–2013): implications for management", pp. 97–104 in Crocodiles Proceedings of the 22nd Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- ↑ Caldicott, D. G.; Croser, D.; Manolis, C.; Webb, G.; Britton, A. (2005). "Crocodile attack in Australia: an analysis of its incidence and review of the pathology and management of crocodilian attacks in general". Wilderness & environmental medicine. 16 (3): 143–159. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(2005)16[143:CAIAAA]2.0.CO;2. PMID 16209470.

- ↑ Nichols, T.; Letnic, M. (2008). "Problem crocodiles: reducing the risk of attacks by Crocodylus porosus in Darwin Harbour, Northern Territory, Australia". Urban herpetology. 3. pp. 503–511.

- ↑ "Rise in Borneo crocodile attacks may be linked to Malaysia's logging, palm oil, expert says". Associated Press via International Herald Tribune. 25 April 2007. Archived from the original on 11 August 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ↑ "Woman saves daughter from crocodile". Telegraph. 14 March 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "KalingaTimes.com: Two injured in crocodile attack in Orissa". Web.archive.org. 7 June 2008. Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "Croc kills woman 4 years after her sister's death – TODAY.com". Today.msnbc.msn.com. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "Crocodile kills man accused of illegal logging in Myanmar wildlife sanctuary". Associated Press via International Herald Tribune. 20 April 2008. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Crocodile Specialist Group – Crocodilian Attacks". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Walsh, B.; Whitehead, P. J. (1993). "Problem crocodiles, Crocodylus porosus, at Nhulunbuy, Northern Territory: an assessment of relocation as a management strategy". Wildlife Research. 20 (1): 127–135. doi:10.1071/WR9930127.

- ↑ Delaney, R., Fukuda, Y., & Saalfeld, K. (2009). SALTWATER CROCODILE (Crocodylus porosus) MANAGEMENT PROGRAM. Northern Territory Government, Department of Natural Resources, Environment, the Arts and Sport.

- ↑ Sideleau, B., & Britton, A. R. C. (2012). "A preliminary analysis of worldwide crocodilian attacks", pp. 111–114 in Crocodiles Proceedings of the 21st Working Meeting of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- ↑ Webb, G. J. W.; Messel, H. (1979). "Wariness in Crocodylus porosus (Reptilia: Crocodilidae)". Wildlife Research. 6 (2): 227–234. doi:10.1071/WR9790227.