Transferrin

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

| Transferrin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Transferrin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00405 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001156 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00182 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1lcf | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1lcf | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 161 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1lfc | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Transferrins are iron-binding blood plasma glycoproteins that control the level of free iron (Fe) in biological fluids.[3] Human transferrin is encoded by the TF gene.[4]

Transferrin glycoproteins bind iron tightly, but reversibly. Although iron bound to transferrin is less than 0.1% (4 mg) of total body iron, it forms the most vital iron pool with the highest rate of turnover (25 mg/24 h). Transferrin has a molecular weight of around 80 KDa and contains two specific high-affinity Fe(III) binding sites. The affinity of transferrin for Fe(III) is extremely high (association constant is 1020 M−1 at pH 7.4)[5] but decreases progressively with decreasing pH below neutrality.

When not bound to iron, transferrin is known as "apotransferrin" (see also apoprotein).

Transport mechanism

When a transferrin protein loaded with iron encounters a transferrin receptor on the surface of a cell, e.g., erythroid precursors in the bone marrow, it binds to it and is transported into the cell in a vesicle by receptor-mediated endocytosis. The pH of the vesicle is reduced by hydrogen ion pumps (H+

ATPases) to about 5.5, causing transferrin to release its iron ions. The receptor with its ligand bound transferrin is then transported through the endocytic cycle back to the cell surface, ready for another round of iron uptake.

Each transferrin molecule has the ability to carry two iron ions in the ferric form (Fe3+

).

The gene coding for transferrin in humans is located in chromosome band 3q21.[4]

Medical professionals may check serum transferrin level in iron deficiency and in iron overload disorders such as hemochromatosis.

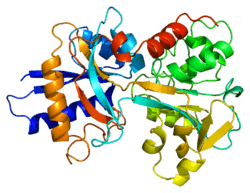

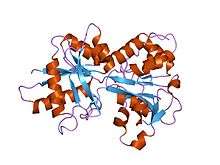

Structure

In humans, transferrin consists of a polypeptide chain containing 679 amino acids and two carbohydrate chains. The protein is composed of alpha helices and beta sheets that form two domains.[6] The N- and C- terminal sequences are represented by globular lobes and between the two lobes is an iron-binding site.

The amino acids which bind the iron ion to the transferrin are identical for both lobes; two tyrosines, one histidine, and one aspartic acid. For the iron ion to bind, an anion is required, preferably carbonate (CO2−

3).[6]

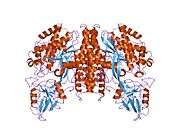

Transferrin also has a transferrin iron-bound receptor; it is a disulfide-linked homodimer.[7] In humans, each monomer consists of 760 amino acids. It enables ligand bonding to the transferrin, as each monomer can bind to one or two molecules of iron. Each monomer consists of three domains: the protease, the helical, and the apical domains. The shape of a transferrin receptor resembles a butterfly based on the intersection of three clearly shaped domains.[6]

Tissue distribution

The liver is the main site of transferrin synthesis but other tissues and organs, including the brain, also produce transferrin. The main role of transferrin is to deliver iron from absorption centers in the duodenum and white blood cell macrophages to all tissues. Transferrin plays a key role in areas where erythropoiesis and active cell division occur.[7] The receptor helps maintain iron homeostasis in the cells by controlling iron concentrations.[7]

Immune system

Transferrin is also associated with the innate immune system. It is found in the mucosa and binds iron, thus creating an environment low in free iron that impedes bacterial survival in a process called iron withholding. The level of transferrin decreases in inflammation.[10]

Role in disease

An increased plasma transferrin level is often seen in patients suffering from iron deficiency anemia, during pregnancy, and with the use of oral contraceptives, reflecting an increase in transferrin protein expression. When plasma transferrin levels rise, there is a reciprocal decrease in percent transferrin iron saturation, and a corresponding increase in total iron binding capacity in iron deficient states[11] A decreased plasma transferrin can occur in iron overload diseases and protein malnutrition. An absence of transferrin results from a rare genetic disorder known as atransferrinemia, a condition characterized by anemia and hemosiderosis in the heart and liver that leads to heart failure and many other complications.

Transferrin and its receptor have been shown to diminish tumour cells when the receptor is used to attract antibodies.[7]

Other effects

Carbohydrate deficient transferrin increases in the blood with heavy ethanol consumption and can be monitored through laboratory testing.[12]

Transferrin is an acute phase protein and is therefore seen to decrease in inflammation, cancers, and certain diseases.[13]

Pathology

Atransferrinemia is associated with a deficiency in transferrin.

In nephrotic syndrome, urinary loss of transferrin, along with other serum proteins such as thyroxine-binding globulin, gammaglobulin, and anti-thrombin III, can manifest as iron-resistant microcytic anemia.

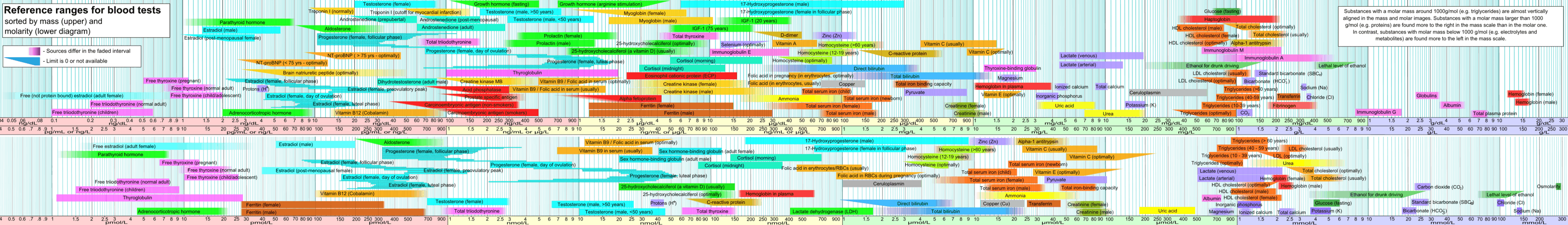

Reference ranges

An example reference range for transferrin is 204–360 mg/dL.[14] Laboratory test results should always be interpreted using the reference range provided by the laboratory that performed the test.

A high transferrin level may indicate an iron deficiency anemia. Levels of serum iron and total iron binding capacity (TIBC) are used in conjunction with transferrin to specify any abnormality. See interpretation of TIBC. Low transferrin likely indicates malnutrition.

Interactions

Transferrin has been shown to interact with insulin-like growth factor 2[15] and IGFBP3.[16] Transcriptional regulation of transferrin is upregulated by retinoic acid.[17]

Related proteins

Members of the family include blood serotransferrin (or siderophilin, usually simply called transferrin); lactotransferrin (lactoferrin); milk transferrin; egg white ovotransferrin (conalbumin); and membrane-associated melanotransferrin.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ Crichton RR, Charloteaux-Wauters M (May 1987). "Iron transport and storage". European Journal of Biochemistry / FEBS. 164 (3): 485–506. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11155.x. PMID 3032619.

- 1 2 Yang F, Lum JB, McGill JR, Moore CM, Naylor SL, van Bragt PH, Baldwin WD, Bowman BH (May 1984). "Human transferrin: cDNA characterization and chromosomal localization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (9): 2752–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.9.2752. PMC 345148

. PMID 6585826.

. PMID 6585826. - ↑ Aisen P, Leibman A, Zweier J (Mar 1978). "Stoichiometric and site characteristics of the binding of iron to human transferrin" (PDF). The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 253 (6): 1930–7. PMID 204636.

- 1 2 3 "Transferrin Structure". St. Edward's University. 2005-07-18. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Macedo MF, de Sousa M (Mar 2008). "Transferrin and the transferrin receptor: of magic bullets and other concerns". Inflammation & Allergy Drug Targets. 7 (1): 41–52. doi:10.2174/187152808784165162. PMID 18473900.

- ↑ PDB: 1suv; Cheng Y, Zak O, Aisen P, Harrison SC, Walz T (Feb 2004). "Structure of the human transferrin receptor-transferrin complex". Cell. 116 (4): 565–76. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00130-8. PMID 14980223.

- ↑ PDB: 2nsu; Hafenstein S, Palermo LM, Kostyuchenko VA, Xiao C, Morais MC, Nelson CD, Bowman VD, Battisti AJ, Chipman PR, Parrish CR, Rossmann MG (Apr 2007). "Asymmetric binding of transferrin receptor to parvovirus capsids". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (16): 6585–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701574104. PMC 1871829

. PMID 17420467.

. PMID 17420467. - ↑ Ritchie RF, Palomaki GE, Neveux LM, Navolotskaia O, Ledue TB, Craig WY (1999). "Reference distributions for the negative acute-phase serum proteins, albumin, transferrin and transthyretin: a practical, simple and clinically relevant approach in a large cohort". Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 13 (6): 273–9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1999)13:6<273::AID-JCLA4>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID 10633294.

- ↑ Miller JL. Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Common and Curable Disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2013;3(7):10.1101/cshperspect.a011866 a011866. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a011866.

- ↑ Sharpe PC (Nov 2001). "Biochemical detection and monitoring of alcohol abuse and abstinence". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 38 (Pt 6): 652–64. doi:10.1258/0004563011901064. PMID 11732647.

- ↑ Jain S, Gautam V, Naseem S (Jan 2011). "Acute-phase proteins: As diagnostic tool". Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences. 3 (1): 118–27. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.76489. PMC 3053509

. PMID 21430962.

. PMID 21430962. - ↑ "Normal Reference Range Table". Interactive Case Study Companion to Pathlogical Basis of Disease. The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Archived from the original on 2011-12-25. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

Kumar V, Hagler HK (1999). Interactive Case Study Companion to Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease (6th Edition (CD-ROM for Windows & Macintosh, Individual) ed.). W B Saunders Co. ISBN 0-7216-8462-9. - ↑ Storch S, Kübler B, Höning S, Ackmann M, Zapf J, Blum W, Braulke T (Dec 2001). "Transferrin binds insulin-like growth factors and affects binding properties of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3". FEBS Letters. 509 (3): 395–8. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03204-5. PMID 11749962.

- ↑ Weinzimer SA, Gibson TB, Collett-Solberg PF, Khare A, Liu B, Cohen P (Apr 2001). "Transferrin is an insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 binding protein". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 86 (4): 1806–13. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.4.7380. PMID 11297622.

- ↑ Hsu SL, Lin YF, Chou CK (Apr 1992). "Transcriptional regulation of transferrin and albumin genes by retinoic acid in human hepatoma cell line Hep3B". The Biochemical Journal. 283 (2): 611–5. doi:10.1042/bj2830611. PMC 1131079

. PMID 1315521.

. PMID 1315521. - ↑ M Ching-Ming Chung (October 1984). "Structure and function of transferrin". Biochemical Education. 12 (4): 146–154. doi:10.1016/0307-4412(84)90118-3.

Further reading

- Hershberger CL, Larson JL, Arnold B, Rosteck PR, Williams P, DeHoff B, Dunn P, O'Neal KL, Riemen MW, Tice PA (Dec 1991). "A cloned gene for human transferrin". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 646: 140–54. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb18573.x. PMID 1809186.

- Bowman BH, Yang FM, Adrian GS (1989). "Transferrin: evolution and genetic regulation of expression". Advances in Genetics. Advances in Genetics. 25: 1–38. doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60457-5. ISBN 9780120176250. PMID 3057819.

- Parkkinen J, von Bonsdorff L, Ebeling F, Sahlstedt L (Aug 2002). "Function and therapeutic development of apotransferrin". Vox Sanguinis. 83 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): 321–6. doi:10.1111/j.1423-0410.2002.tb05327.x. PMID 12617162.

External links

- Transferrin at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)