Ceruloplasmin

| CP | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | CP, CP-2, ceruloplasmin (ferroxidase), Ceruloplasmin | ||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 117700 MGI: 88476 HomoloGene: 75 GeneCards: CP | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

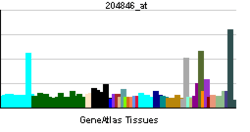

| RNA expression pattern | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| More reference expression data | |||||||||||||||||

| Orthologs | |||||||||||||||||

| Species | Human | Mouse | |||||||||||||||

| Entrez | |||||||||||||||||

| Ensembl | |||||||||||||||||

| UniProt | |||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 3: 149.16 – 149.22 Mb | Chr 3: 19.96 – 20.01 Mb | |||||||||||||||

| PubMed search | [1] | [2] | |||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

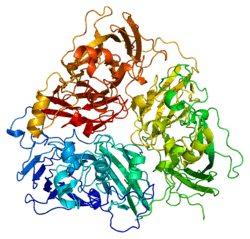

Ceruloplasmin (or caeruloplasmin) is a ferroxidase enzyme that in humans is encoded by the CP gene.[3][4][5]

Ceruloplasmin is the major copper-carrying protein in the blood, and in addition plays a role in iron metabolism. It was first described in 1948.[6] Another protein, hephaestin, is noted for its homology to ceruloplasmin, and also participates in iron and probably copper metabolism.

Function

Ceruloplasmin is an enzyme (EC 1.16.3.1) synthesized in the liver containing 6 atoms of copper in its structure.[7] Ceruloplasmin carries more than 95% of the total copper in healthy human plasma.[8] The rest is accounted for by macroglobulins. Ceruloplasmin exhibits a copper-dependent oxidase activity, which is associated with possible oxidation of Fe2+ (ferrous iron) into Fe3+ (ferric iron), therefore assisting in its transport in the plasma in association with transferrin, which can carry iron only in the ferric state.[9] The molecular weight of human ceruloplasmin is reported to be 151kDa.

Regulation

A cis-regulatory element called the GAIT element is involved in the selective translational silencing of the Ceruloplasmin transcript.[10] The silencing requires binding of a cytosolic inhibitor complex called IFN-gamma-activated inhibitor of translation (GAIT) to the GAIT element.[11]

Clinical significance

Like any other plasma protein, levels drop in patients with hepatic disease due to reduced synthesizing capabilities.

Mechanisms of low ceruloplasmin levels:

- Gene expression genetically low (aceruloplasminemia)

- Copper levels are low in general

- Malnutrition/trace metal deficiency in the food source

- Copper does not cross the intestinal barrier due to ATP7A deficiency (Menkes disease)

- Delivery of copper into the lumen of the ER-Golgi network is absent in hepatocytes due to absent ATP7B (Wilson's disease)

Copper availability doesn't affect the translation of the nascent protein. However, the apoenzyme without copper is unstable. Apoceruloplasmin is largely degraded intracellularly in the hepatocyte and the small amount that is released has a short circulation half life of 5 hours as compared to the 5.5 days for the holo-ceruloplasmin.

Mutations in the ceruloplasmin gene (CP), which are very rare, can lead to the genetic disease aceruloplasminemia, characterized by hyperferritinemia with iron overload. In the brain, this iron overload may lead to characteristic neurologic signs and symptoms, such as cerebellar ataxia, progressive dementia, and extrapyramidal signs. Excess iron may also deposit in the liver, pancreas, and retina, leading to cirrhosis, endocrine abnormalities, and loss of vision, respectively.

Deficiency

Lower-than-normal ceruloplasmin levels may indicate the following:

- Wilson disease (a rare (UK incidence 2/100,000) copper storage disease)[12]

- Menkes disease (Menkes kinky hair syndrome) (rare - UK incidence 1/100,000)

- Overdose of Vitamin C

- Copper deficiency

- Aceruloplasminemia[13]

Excess

Greater-than-normal ceruloplasmin levels may indicate or be noticed in:

- copper toxicity / zinc deficiency

- pregnancy

- oral contraceptive pill use[14]

- lymphoma

- acute and chronic inflammation (it is an acute-phase reactant)

- rheumatoid arthritis

- Angina[15]

- Alzheimer's disease[16]

- Schizophrenia[17]

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder[18]

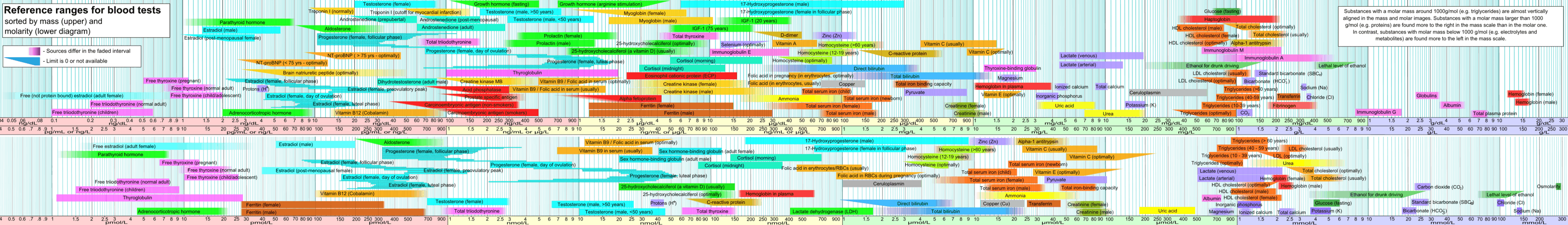

Reference ranges

References

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ Takahashi N, Ortel TL, Putnam FW (Jan 1984). "Single-chain structure of human ceruloplasmin: the complete amino acid sequence of the whole molecule". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (2): 390–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.2.390. PMC 344682

. PMID 6582496.

. PMID 6582496. - ↑ Koschinsky ML, Funk WD, van Oost BA, MacGillivray RT (Jul 1986). "Complete cDNA sequence of human preceruloplasmin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (14): 5086–90. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.14.5086. PMC 323895

. PMID 2873574.

. PMID 2873574. - ↑ Royle NJ, Irwin DM, Koschinsky ML, MacGillivray RT, Hamerton JL (May 1987). "Human genes encoding prothrombin and ceruloplasmin map to 11p11-q12 and 3q21-24, respectively". Somatic Cell and Molecular Genetics. 13 (3): 285–92. doi:10.1007/BF01535211. PMID 3474786.

- ↑ Holmberg CG, Laurell CB (1948). "Investigations in serum copper. II. Isolation of the Copper containing protein, and a description of its properties". Acta Chem Scand. 2: 550–56. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.02-0550.

- ↑ O'Brien PJ, Bruce WR (2009). Endogenous Toxins: Targets for Disease Treatment and Prevention, 2 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 405–6. ISBN 978-3-527-32363-0.

- ↑ Hellman NE, Gitlin JD (2002). "Ceruloplasmin metabolism and function". Annual Review of Nutrition. 22: 439–58. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.012502.114457. PMID 12055353.

- ↑ Song D, Dunaief JL (2013). "Retinal iron homeostasis in health and disease". Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 5: 24. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2013.00024. PMID 23825457.

- ↑ Sampath P, Mazumder B, Seshadri V, Fox PL (Mar 2003). "Transcript-selective translational silencing by gamma interferon is directed by a novel structural element in the ceruloplasmin mRNA 3' untranslated region". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (5): 1509–19. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.5.1509-1519.2003. PMC 151701

. PMID 12588972.

. PMID 12588972. - ↑ Mazumder B, Sampath P, Fox PL (Oct 2005). "Regulation of macrophage ceruloplasmin gene expression: one paradigm of 3'-UTR-mediated translational control". Molecules and Cells. 20 (2): 167–72. PMID 16267389.

- ↑ Scheinberg IH, Gitlin D (Oct 1952). "Deficiency of ceruloplasmin in patients with hepatolenticular degeneration (Wilson's disease)". Science. 116 (3018): 484–5. doi:10.1126/science.116.3018.484. PMID 12994898.

- ↑ Gitlin JD (Sep 1998). "Aceruloplasminemia". Pediatric Research. 44 (3): 271–6. doi:10.1203/00006450-199809000-00001. PMID 9727700.

- ↑ Elkassabany NM, Meny GM, Doria RR, Marcucci C (Apr 2008). "Green plasma-revisited". Anesthesiology. 108 (4): 764–5. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181672668. PMID 18362615.

- ↑ Ziakas A, Gavrilidis S, Souliou E, Giannoglou G, Stiliadis I, Karvounis H, Efthimiadis G, Mochlas S, Vayona MA, Hatzitolios A, Savopoulos C, Pidonia I, Parharidis G (2009). "Ceruloplasmin is a better predictor of the long-term prognosis compared with fibrinogen, CRP, and IL-6 in patients with severe unstable angina". Angiology. 60 (1): 50–9. doi:10.1177/0003319708314249. PMID 18388036.

- ↑ Lutsenko S, Gupta A, Burkhead JL, Zuzel V (Aug 2008). "Cellular multitasking: the dual role of human Cu-ATPases in cofactor delivery and intracellular copper balance". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 476 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2008.05.005. PMC 2556376

. PMID 18534184.

. PMID 18534184. - ↑ Wolf TL, Kotun J, Meador-Woodruff JH (Sep 2006). "Plasma copper, iron, ceruloplasmin and ferroxidase activity in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research. 86 (1-3): 167–71. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.027. PMID 16842975.

- ↑ Virit O, Selek S, Bulut M, Savas HA, Celik H, Erel O, Herken H (2008). "High ceruloplasmin levels are associated with obsessive compulsive disorder: a case control study". Behavioral and Brain Functions. 4: 52. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-4-52. PMC 2596773

. PMID 19017404.

. PMID 19017404.

Further reading

- Hellman NE, Gitlin JD (2002). "Ceruloplasmin metabolism and function". Annual Review of Nutrition. 22: 439–58. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.012502.114457. PMID 12055353.

- Mazumder B, Seshadri V, Fox PL (Feb 2003). "Translational control by the 3'-UTR: the ends specify the means". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 28 (2): 91–8. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00002-1. PMID 12575997.

- Giurgea N, Constantinescu MI, Stanciu R, Suciu S, Muresan A (Feb 2005). "Ceruloplasmin - acute-phase reactant or endogenous antioxidant? The case of cardiovascular disease". Medical Science Monitor. 11 (2): RA48–51. PMID 15668644.

- Kingston IB, Kingston BL, Putnam FW (Dec 1977). "Chemical evidence that proteolytic cleavage causes the heterogeneity present in human ceruloplasmin preparations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (12): 5377–81. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5377. PMC 431726

. PMID 146197.

. PMID 146197. - Polosatov MV, Klimov PK, Masevich CG, Samartsev MA, Wünsch E (Apr 1979). "Interaction of synthetic human big gastrin with blood proteins of man and animals". Acta Hepato-Gastroenterologica. 26 (2): 154–9. PMID 463490.

- Schilsky ML, Stockert RJ, Pollard JW (Dec 1992). "Caeruloplasmin biosynthesis by the human uterus". The Biochemical Journal. 288 (2): 657–61. doi:10.1042/bj2880657. PMC 1132061

. PMID 1463466.

. PMID 1463466. - Walker FJ, Fay PJ (Feb 1990). "Characterization of an interaction between protein C and ceruloplasmin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (4): 1834–6. PMID 2105310.

- Fleming RE, Gitlin JD (May 1990). "Primary structure of rat ceruloplasmin and analysis of tissue-specific gene expression during development". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (13): 7701–7. PMID 2332446.

- Yang FM, Friedrichs WE, Cupples RL, Bonifacio MJ, Sanford JA, Horton WA, Bowman BH (Jun 1990). "Human ceruloplasmin. Tissue-specific expression of transcripts produced by alternative splicing". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (18): 10780–5. PMID 2355023.

- Yang F, Naylor SL, Lum JB, Cutshaw S, McCombs JL, Naberhaus KH, McGill JR, Adrian GS, Moore CM, Barnett DR (May 1986). "Characterization, mapping, and expression of the human ceruloplasmin gene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (10): 3257–61. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.10.3257. PMC 323492

. PMID 3486416.

. PMID 3486416. - Mercer JF, Grimes A (Jul 1986). "Isolation of a human ceruloplasmin cDNA clone that includes the N-terminal leader sequence". FEBS Letters. 203 (2): 185–90. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(86)80739-6. PMID 3755405.

- Rask L, Valtersson C, Anundi H, Kvist S, Eriksson U, Dallner G, Peterson PA (Jan 1983). "Subcellular localization in normal and vitamin A-deficient rat liver of vitamin A serum transport proteins, albumin, ceruloplasmin and class I major histocompatibility antigens". Experimental Cell Research. 143 (1): 91–102. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(83)90112-X. PMID 6337857.

- Kressner MS, Stockert RJ, Morell AG, Sternlieb I (1984). "Origins of biliary copper". Hepatology. 4 (5): 867–70. doi:10.1002/hep.1840040512. PMID 6479854.

- Takahashi N, Bauman RA, Ortel TL, Dwulet FE, Wang CC, Putnam FW (Jan 1983). "Internal triplication in the structure of human ceruloplasmin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (1): 115–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.1.115. PMC 393320

. PMID 6571985.

. PMID 6571985. - Dwulet FE, Putnam FW (Feb 1981). "Complete amino acid sequence of a 50,000-dalton fragment of human ceruloplasmin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 78 (2): 790–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.2.790. PMC 319888

. PMID 6940148.

. PMID 6940148. - Kingston IB, Kingston BL, Putnam FW (Apr 1980). "Primary structure of a histidine-rich proteolytic fragment of human ceruloplasmin. I. Amino acid sequence of the cyanogen bromide peptides". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 255 (7): 2878–85. PMID 6987229.