Mid-Atlantic accent

The mid-Atlantic accent, or Transatlantic accent,[1][2][3] is a consciously acquired accent of English, intended to blend together the "standard" speech of both American English and British Received Pronunciation. Spoken mostly in the early twentieth century, it is not a vernacular American accent native to any location, but an affected set of speech patterns whose "chief quality was that no Americans actually spoke it unless educated to do so".[4] The accent is therefore best associated with the American upper class, theater, and film industry of the 1930s and 1940s,[5] largely taught in private independent preparatory schools especially in the American Northeast and in acting schools.[6] The accent's overall usage sharply declined following World War II.[7]

Generally a North American phenomenon, the terms "Transatlantic" and "mid-Atlantic accent" are sometimes used alternatively, in Britain, to refer (often critically) to the speech of British public figures (often in the entertainment industry) who affect quasi-American pronunciation features.

Historical use

Elite use

According to sociolinguist William Labov, "r-less pronunciation, following Received Pronunciation, was taught as a model of correct, international English by schools of speech, acting and elocution in the United States up to the end of World War II."[7] Mid-Atlantic English was employed by some American elites in the Northeastern United States. Prior to World War II, some American elite institutions cultivated a norm influenced by the Received Pronunciation of Southern England as an international norm of English pronunciation. Recordings of American presidents Grover Cleveland (raised in Central New York) and Ohio-native William McKinley show their oratory employed a Mid-Atlantic accent. Theodore Roosevelt, McKinley's successor and a native of New York, had a more natural non-rhotic, upper-class accent.

Upper-class Americans (outside the film industry) known for speaking with a consistent mid-Atlantic accent include William F. Buckley, Jr.,[8] Gore Vidal, Franklin D. and Eleanor Roosevelt, George Plimpton,[9][10] Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (who began affecting it while at Miss Porter's School and maintained it lifelong),[11] Norman Mailer,[12] Diana Vreeland,[13] and Cornelius Vanderbilt IV,[14] all of whom were raised, partly or primarily, in the Northeastern United States (and some additionally educated in London). The monologuist Ruth Draper's recorded "The Italian Lesson" gives an example of this East Coast American upper class diction of the 1940s.

The mid-Atlantic speaking style among the educated wealthy was associated with white Americans of the urban Northeast. In and around Boston, Massachusetts, for example, the accent was characteristic, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, of the local elite: the Boston Brahmins. Examples of people described as having a "Boston Brahmin accent" include Charles Eliot Norton,[15] John Brooks Wheelwright,[16] George C. Homans,[17] McGeorge Bundy,[18] Elliot Richardson,[19] George Plimpton (though he was actually a lifelong member of the New York City elite),[20] and John Kerry,[21] who has noticeably reduced this accent since his early adulthood. In the New York metropolitan area, particularly including its affluent Westchester County suburbs and the North Shore of Long Island, other terms for the local mid-Atlantic pronunciation and accompanying facial behavior include "Locust Valley lockjaw" or "Larchmont lockjaw", named for the stereotypical clenching of the speaker's jaw muscles to achieve an exaggerated enunciation quality.[22] The related term "boarding-school lockjaw" has also been used to describe the prestigious accent once taught at expensive Northeastern independent schools.[22]

Recordings of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who came from a privileged New York City family and was educated at Groton, a private Massachusetts preparatory school, had a number of characteristic patterns. His speech is non-rhotic; one of Roosevelt's most frequently heard speeches has a falling diphthong in the word fear, which distinguishes it from other forms of surviving non-rhotic speech in the United States.[23] "Linking R" appears in Roosevelt's delivery of the words "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself"; compare also Roosevelt's delivery of the words "naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan".[24]

After the accent's decline following the end of World War II, this American version of a "posh" accent has all but disappeared even among the American upper classes. The clipped, non-rhotic English of George Plimpton and William F. Buckley, Jr. were vestigial examples,[5] though subtle traces can be detected to this day, mostly among older generations hailing from wealthier pockets around East Coast cities such as Boston, New York City and Philadelphia.

Theatrical and cinematic use

Being spoken by the American social elite in the early 1900s, this accent consequently also became a popular affectation in the theater and other forms of high culture in North America. As used by actors, the mid-Atlantic accent is also known by various other names, including American theater standard or American stage speech.[25] The codification of the mid-Atlantic accent in writing, particularly for theatrical training, is often credited to American elocutionist Edith Warman Skinner in the 1930s,[4][25] best known for her 1942 instructional text Speak with Distinction.[3] Skinner, who often referred to this accent (or register) as "Good (American) Speech" or "Eastern Standard", described it as the appropriate American pronunciation for "classics and elevated texts".[26] A linguistic prescriptivist, she vigorously drilled her students in learning the accent at the Carnegie Institute of Technology and, later, the Juilliard School.[4]

American cinema began in the early 1900s in New York City and Philadelphia before becoming largely transplanted to Los Angeles beginning in the mid-1910s. With the evolution of talkies in the late 1920s, voice was first heard in motion pictures. It was then that the majority of audiences first heard Hollywood actors speaking predominantly in the elevated stage pronunciation of the mid-Atlantic accent. Many adopted it starting out in the theatre, and others simply affected it to help their careers on and off in films.

Among exemplary speakers of this accent from Hollywood's Golden Era are American actors like Tyrone Power,[27] Bette Davis,[27] Katharine Hepburn,[28] and Vincent Price;[3] Canadian actor Christopher Plummer;[3] and Cary Grant, who arrived in the United States from England aged 16,[29] and whose accent is arguably a more natural and unconscious mixture of British and American features. Roscoe Lee Browne, defying roles typically cast for African American actors, also consistently spoke with a mid-Atlantic accent.[30]

Contemporary use

Although it has largely disappeared as a standard of high society and high culture, the Transatlantic accent has still been heard in some recent media for the sake of stylistic effect. It is occasionally affected by contemporary American actors, especially when playing characters intended to be regarded as authoritative, privileged, timeless, or vaguely non-American.

- Elizabeth Banks uses the mid-Atlantic accent in playing the flamboyant, fussy, upper-class character Effie Trinket in the futuristic Hunger Games film series,[2] and also for her character, Pizzaz Miller, on the Comedy Central show Moonbeam City.

- A comedic example of this accent appears in the television sitcom Frasier used by the snobbish Crane brothers, who are played by Kelsey Grammer and David Hyde Pierce.[3]

- In the Star Wars film franchise, the character Darth Vader (voiced by James Earl Jones) noticeably speaks with a deep bass tone and a mid-Atlantic accent to suggest his position of high authority; Princess Leia (played by Carrie Fisher) and Queen Amidala (played by Natalie Portman) also use this accent when switching to a formal speaking register in political situations.[3]

- A classic Mid-Atlantic accent in film was the "lockjaw" speech pattern affected by Joanna Barnes in her portrayal of anti-Semitic, pretentious, spoiled rich socialite, Gloria Upson in the 1958 film, Auntie Mame. Barnes' entertaining parody earned her a Golden Globe nomination for "New Star of the Year." As a stockbroker's daughter born and raised in a Boston socialite family, as well as educated at Milton Academy and then a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Smith College. Barnes was naturally familiar with the accent which she assumed for many of her film and television roles.

- One of the classic Mid-Atlantic accents on television was the "lockjaw" speech pattern affected by Jim Backus in his portrayal of millionaire Thurston Howell III on the situation comedy Gilligan's Island.

- In 1983's film, Trading Places, Dan Aykroyd's character Louis Winthorpe III affected a Mid-Atlantic accent as he said of Eddie Murphy's Billy Ray Valentine, "He was wearing my Harvard tie--can you believe it? My Harvard Tie! Like, oh sure, HE went to Harvard!"

- David Tench (played by Drew Forsythe), who was a fictional animated Australian TV host from David Tench Tonight, often used a transatlantic accent. Although, most of the time, he had a cultivated Australian accent which vacillated into the transatlantic accent.

- Harry Shearer's vocal portrayal of Mr. Burns, Kelsey Grammer's vocal portrayal of Sideshow Bob, and Dan Castellaneta's vocal portrayal of Sideshow Mel in The Simpsons.

- Jon Lovitz spoke in a highly theatrical Mid-Atlantic accent for his character Master Thespian on Saturday Night Live.

- Tabitha St. Germain uses a Mid-Atlantic accent for the voice of Rarity in My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic.

- For her role as Amelia Earhart, Amy Adams spoke with a Mid-Atlantic accent in Night at the Museum 2 (2009), probably to give the character a confident air but would otherwise seem an odd choice for a portrayal of the famous flier who was a "midwesterner" - born (and spent her first twelve years) in Aitchison, Kansas, next five years in Des Moines, Iowa, and high school in Chicago, Illinois. Film clips of the real "tomboy" Earhart reveal a midwestern accent.

- Dodo Bellacourt in the series Another Period speaks with an exaggerated Mid-Atlantic accent.

- Asian films dubbed into English in Hong Kong often use Mid-Atlantic accents, most notably the English-dubbed versions of many entries of the Godzilla series, numerous films produced by Shaw Brothers and most of Bruce Lee's filmography. The accent was used in a somewhat utilitarian fashion as the dubbing casts featured English-speaking ex-pats living in Hong Kong from many different countries including Britain, the U.S. and Australia, and the dubs themselves were meant for all English-speaking territories so a neutral accent was preferred.

- Evan Peters employs a Mid-Atlantic accent on American Horror Story: Hotel (as James Patrick March, a ghostly serial killer from the 1920s), as does Mare Winningham (as March's accomplice, Miss Evers).

- In the 2015 film The Man From U.N.C.L.E., Henry Cavill speaks with a Mid-Atlantic accent for his character Napoleon Solo.

Phonology

Mid-Atlantic accents were carefully taught at American boarding schools and also for use in the American theater prior to the 1960s (after which it fell out of vogue).[31] It is still taught to actors for use in playing historical characters.[32] A version codified by voice coach Edith Skinner was once widely taught in acting schools of the earlier twentieth century. This traditional standard of the mid-Atlantic accent is noticeably non-rhotic, or "drops" the r sound whenever not before a vowel (a feature imitating the London norm and still typical today of both upper- as well as lower-class London English). The mid-Atlantic accent's vowel sounds attempt to approximate a middle ground between standard broadcasting accents of the United States and England.

Consonants

A table containing the consonant phonemes is given below:

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||||

| Affricate | tʃ | dʒ | ||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | h | |||||

| Approximant | l | ɹ | j | (ʍ) | w | |||||||||

- The Mid-Atlantic accent lacks the Wine–whine merger: The consonants spelled w and wh are pronounced differently; words spelled with wh are pronounced as "hw" (/ʍ/). /ʍ/ is often analyzed as a consonant cluster of /hw/.

- Rhoticity (or r-fulness): Unlike General American which is firmly rhotic, pronouncing the r sound in all environments, including after vowels, such as in pearl, car, and court,[33][34] in Mid-Atlantic /r/ is only pronounced when it is immediately followed by a vowel sound. Where GA pronounces /r/ before a consonant and at the end of an utterance, Mid-Atlantic either has nothing (if the preceding vowel is /ɔː/ or /ɑː/) or has a schwa instead (the resulting sequences are diphthongs or triphthongs). Similarly, where GA has r-coloured vowels (/ɚ/ or /ɝ/, as in cupboard or bird), Mid-Atlantic has plain vowels /ə/ or /ɜː/. Linking R is used, but intrusive R is not permitted.[35]

- Unlike American English dialects, Mid-Atlantic lacks T-glottalization and flapping. In General American, /t/ is pronounced as a glottal stop [ʔ] before a consonant (such as a syllabic nasal), as in button [ˈbʌ̈ʔn], and sometimes at the end of a word, as in what [wʌ̈ʔ]. /t/ and /d/ become an alveolar flap, written [ɾ], between vowels or liquids (l and r), as in water [ˈwɑɾɚ] (

listen), party [ˈpʰɑɹɾi], model [ˈmɑɾ.ɫ̩], and what is it? [wʌ̈ɾˈɪzɪt]. Mid-Atlantic pronounces all of these as a t ([tʰ]).

listen), party [ˈpʰɑɹɾi], model [ˈmɑɾ.ɫ̩], and what is it? [wʌ̈ɾˈɪzɪt]. Mid-Atlantic pronounces all of these as a t ([tʰ]). - Preservation of yod: After alveolar consonants /tj/, /dj/, /nj/, and optionally /sj/ and /lj/[36] (as in tune, due, new, pursue, evolution), the "y" sound /j/ is preserved in Mid-Atlantic, as in Received Pronunciation. Most American dialects drop it in many words, for example, new ("nyoo") /njuː/ becomes ("noo") [nu̟ː], duke /djuːk/ becomes [du̟ːk], and tube /tjuːb/ becomes [tʰu̟ːb].[37]

- /h/ may be voiced ([ɦ]) between two vowel sounds.

Vowels

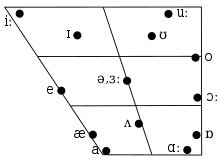

Monophthongs[38]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| long | short | long | short | long | short | |

| Close | iː | ɪ | uː | ʊ | ||

| Mid | e | ɜː | ə* | ɔː | o* | |

| Near-open | æ | ʌ | ||||

| Open | a | ɑː | ɒ | |||

* only occurs in unstressed syllables

| Open to Open-mid Monophthongs | ||||||||

| Example | IPA | Western American | General American | Inland Northern | New York | Boston | Mid-Atlantic[39] | Received Pronunciation |

| bath | /ɑː/ | [æ] | [æ~ɛə~eə] | [æ] | [ɛə~æ~ä(:)] | [a] ( |

[ɑː] | |

| ban, tram | /æ/ | [æ~ɛə~eə] | [ɪə~eə~ɛə] | [eə~ɛə] | [æ] ( |

[æ~a] | ||

| bat | /æ/ | [æ] | [æ] | [ɛə~æ] | ||||

| father, ah, spa | /ɑː/ | [ɑ]( [ɒ] ( |

[ɑ] ( |

[ɑ]( [a] ( |

[ä] | [ä(:)] | [ɑː] ( |

[ɑː] |

| lot, bother, wasp | /ɒ/ | [ɒː~ɑː] | [ɒ] ( |

[ɒ] | ||||

| boss, dog, off | [ɒ] ( |

[ɒ] ( [ɑ] ( |

[ɔə~oə~ʊə] | [ɒ~ɔː] | ||||

| bought, all, water | /ɔː/ | [ɔː] ( |

[ɔː~o:] | |||||

- Father-bother distinction and Cot-caught distinction: Mid-Atlantic English distinguishes the vowels in the words like spa and ah with the short o of words like spot and odd, as in RP and Eastern New England. Eastern New England is the only region in North America where these sets of words are distinguished. Other American dialects merge the two, therefore, con and khan are homophones in most American dialects. Mid-Atlantic uses [ɑ:] in spa and [ɒ] in "spot", whereas conservative General American uses [ɑ] for both of them; Western American uses either one indiscriminately for both sets of words due to the cot-caught merger, and the vowel length is solely based on the consonants around it; and Inland Northern uses [ɑ] for both of them, which due to the Northern cities vowel shift can shift to [a].

- Mid-Atlantic also distinguishes the vowels in "cot" [ˈkʰɒt] (

listen) and "caught" [ˈkʰɔːt] (

listen) and "caught" [ˈkʰɔːt] ( listen), and merges the "cloth" set with "cot", rather than "caught".[39] This is the same as in contemporary RP.[42] Most American dialects that distinguish the vowels in cot and caught, on the other hand use the "caught" vowel for the "cloth" set. However the vowels that they use in "cot" and "caught" are different. In a conservative Midwestern accent, the vowels are [ɑ] in cot, which sounds like the father vowel in Mid-Atlantic, and [ɒ] in caught, which is pronounced like cot in Mid-Atlantic. However, many people in this region have the Northern Cities vowel shift, which shifts the caught vowel to cot, and the cot vowel is shifted towards the cat vowel. Approximately half of all Americans can neither produce nor perceive a distinction (without effort) between the vowels [ɑ] and [ɒ] [43] such as in the far Western United States, and in some other regions. In most of the far Western US, cot, caught, cloth, as well as spa, are not distinguished at all. Thus in that region, the Mid-Atlantic spa vowel is used interchangeably with the Mid-Atlantic cot vowel for all of those sets of words.

listen), and merges the "cloth" set with "cot", rather than "caught".[39] This is the same as in contemporary RP.[42] Most American dialects that distinguish the vowels in cot and caught, on the other hand use the "caught" vowel for the "cloth" set. However the vowels that they use in "cot" and "caught" are different. In a conservative Midwestern accent, the vowels are [ɑ] in cot, which sounds like the father vowel in Mid-Atlantic, and [ɒ] in caught, which is pronounced like cot in Mid-Atlantic. However, many people in this region have the Northern Cities vowel shift, which shifts the caught vowel to cot, and the cot vowel is shifted towards the cat vowel. Approximately half of all Americans can neither produce nor perceive a distinction (without effort) between the vowels [ɑ] and [ɒ] [43] such as in the far Western United States, and in some other regions. In most of the far Western US, cot, caught, cloth, as well as spa, are not distinguished at all. Thus in that region, the Mid-Atlantic spa vowel is used interchangeably with the Mid-Atlantic cot vowel for all of those sets of words.

- Spa set: Spelled "a" when not pronounced with the cat vowel.

- Examples: spa, father, ah, khan

- Mid-Atlantic [ɑ:]

- Conservative General American: [ɑ(:)]

- Inland Northern: varies between [ɑ(:)] and [a(:)]

- far Western: varies between [ɑ(:)] and [ɒ(:)]

- Examples: spa, father, ah, khan

- Cot set: spelled "o"

- Examples: cot, con, don

- Mid-Atlantic [ɒ]

- Conservative General American: [ɑ(:)]

- Inland Northern: varies between [ɑ(:)] and [a(:)]

- Far Western: varies between [ɑ(:)] and [ɒ(:)]

- Examples: cot, con, don

- Cloth set: Spelled "o" followed by: f; voiceless th (as in thin, not "the"); s; ng; g; and some words ending in k or c. In some dialects, some of these words are in the cot set.

- Examples: cloth, off, often, cross, soft, chocolate

- Mid-Atlantic [ɒ]

- Conservative General American: [ɒ(:)]

- Inland Northern: varies between [ɒ(:)] and [ɑ(:)]

- Far Western: varies between [ɑ(:)] and [ɒ(:)]

- Examples: cloth, off, often, cross, soft, chocolate

- Caught set: The "aw" vowel, often spelled "au", or "ou" (but not in words such as aunt, or foul, etc.)

- Examples: caught, taught, bought

- Mid-Atlantic [ɔː]

- Conservative General American: [ɒ(:)]

- Inland Northern: varies between [ɒ(:)] and [ɑ(:)]

- Far Western: varies between [ɑ(:)] and [ɒ(:)]

- Examples: caught, taught, bought

- Spa set: Spelled "a" when not pronounced with the cat vowel.

| Other Monophthongs | ||||

| Example | General American | Mid-Atlantic[39] | Received Pronunciation | |

| obey (unstressed) | /ə/ | [ə], [oʊ] | [o][44] ( |

[ə] or [əʊ] |

| met, dress, bread | /ɛ/ | [ɛ] ( |

[ɛ] ( |

[ɛ] |

| about, syrup | /ə/ | [ə][40] | [ə] | [ə] |

| kit, pink, tip | /ɪ/ | [ɪ][40] ( |

[ɪ] ( |

[ɪ] |

| beam, chic | /iː/ | [i(ː)][40] ( |

[iː] ( |

[iː] |

| happy, parties | /i/ | [i][40] ( |

[ɪ] ( |

[ɪ~i] |

| muffin, wasted | /ɨ/ | [ɪ̈~ɪ~ə][40] | [ɪ] | [ɪ~ə] |

| bus, flood | /ʌ/ | [ʌ~ɐ] | [ʌ] | [ʌ] |

| put, could | /ʊ/ | [ʊ][40] | [ʊ] | [ʊ] |

| goose, moon | /uː/ | [u̟ː~ʊu~ʉu~ɵu] | [u] | [u~ʉ] |

| tune, dune, news | /juː/ | [(j)u̟ː~(j)ʊu~(j)ʉu~(j)ɵu] | [juː] | [juː~jʉ] |

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close-mid | eɪ̯ | oʊ̯ |

| Open-mid | ɔɪ̯ | |

| Open | aɪ̯ | ɑʊ̯ |

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | ɪə̯ | ʊə̯ |

| Open-mid | ɛə̯ | ɔə̯ |

| Closing Diphthongs | ||||

| Example | General American | Mid-Atlantic[39] | Received Pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bay | /eɪ/ | [eɪ~ɛ̝ɪ] |

[eɪ] ( |

[eɪ~ɛɪ] ( |

| buy | /aɪ/ | [äɪ] |

[aɪ] ( |

[aɪ] ( |

| bite | [äɪ~ɐɪ~ʌɪ][48] | |||

| boy | /ɔɪ/ | [ɔɪ~oɪ] |

[ɔɪ] ( |

[ɔɪ] ( |

| beau | /oʊ/ | [oʊ~ɔʊ~ʌʊ] |

[oʊ] ( |

[əʊ~ɛʊ~ɒʊ~ɔʊ] ( |

| bough | /aʊ/ | [aʊ~æʊ] |

[ɑʊ] ( |

[aʊ] |

- Like early 20th century Received Pronunciation, in the Mid-Atlantic accent /u/ is a very back and rounded vowel. In most present day dialects in Britain, /u/ is pronounced with the back of the tongue further to the front of the mouth, and the lips unrounded. Some American dialects such as the North Central dialect, the Boston accent have the original pronunciation, whereas in Southern American English, Pennsylvania English, and California English the vowel is quite front and unrounded. In the far Western dialects /u/ is fronted after coronals. In addition, in Britain, over the course of the 20th century, the pronunciation of /oʊ/ changed considerably. To reflect the changes, present day RP dictionaries have started to use /əʊ/ rather than /oʊ/.[42] Many speakers of California English as well as other dialects have also changed the pronunciation of that vowel. Mid-Atlantic still uses the older /oʊ/.[39]

| Centering diphthongs - stressed | ||||

| Example | General American | Mid-Atlantic[39] | RP | |

| bar | /ɑːr/ | [ɑɚ~ɑɹ] |

[ɑːə] ( |

[ɑː][42] |

| beer | /ɪər/ | [iɚ~ɪɚ] |

[ɪə] ( |

[ɪə~ɪː] |

| bear | /eər/ | [ɛɚ] |

[ɛə] ( |

[ɛə~ɛː] |

| boor | /ʊər/ | [ʊɚ~oɹ~ɔɚ] |

[ʊə] ( |

[ʊə~ɔː] |

| boar | /ɔər/ | [ɔə] ( |

[ɔə~ɔː] | |

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Open | aɪ̯ə | ɑʊ̯ə |

| Example | Diagraphene | Mid-Atlantic[39] | Received Pronunciation[51] |

|---|---|---|---|

| tire | [aɪə] | [aɪə] | [aɪə~aːə~aː] |

| tower | [ɑʊə] | [ɑʊə] | [ɑʊə~ɑːə~ɑː] |

| lower | [oʊə] | [oʊə] | [əʊə~əːə~ɜː] |

| layer | [eɪə] | [eɪə] | [eɪə~ɛːə~ɛː] |

| loyal | [ɔɪə] | [ɔɪə] | [ɔɪə~ɔːə] |

Happy tensing

Like conservative dialects of American and British English, but unlike modern General American and many present-day RP speakers, Mid-Atlantic English lacks "happy tensing". That means that the vowel /i/ at the end of words such as "happy" ['hæpɪ] (![]() listen) is pronounced with the SIT vowel [ɪ], rather than the SEAT vowel [i:].[39]

listen) is pronounced with the SIT vowel [ɪ], rather than the SEAT vowel [i:].[39]

Use of [a], [ɑ], [ɒ], and [ɔː]

| General American | Mid-Atlantic | Received Pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| cot | [ɑ] ( |

[ɒ] ( | |

| cloth | [ɒ] ( |

[ɒ] | [ɒ] ( |

| caught | [ɔː] ( | ||

| what | [ʌ] | [ɒ] | |

| bother | [ɑ] | ||

| father | [ɑ:] | ||

| dance | [æ] | [a] | [ɑ:] |

Broad A

Like Received Pronunciation and the Boston accent, the Mid-Atlantic accent contains the bath-trap split, which means that "bath" and "trap" have distinct vowels. However, unlike Received Pronunciation, instead of the father vowel [ɑː], or the General American [æ], the compromise vowel [a] is used for the "broad A" (the "pass" vowel) because it sounds midway between [ɑː] and [æ] which is contrasted with the father vowel [ɑː]. Thus the Mid-Atlantic has an additional phoneme compared to Received Pronunciation. The [a] vowel is used sporadically for /æ/ in Canada, California,[52] and to a lesser extent, the rest of the Western US.[53] However, like the rest of North America, except for Boston, there is no distinction between the "trap" vowel and the "pass" vowel.

| North | West | GA | Boston | Older Boston | Mid-Atlantic | RP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| trap | [æ~ɛə] | [æ~a] | [æ] | [æ~ɛə] | [æ] | [æ] | [æ~a] |

| half, pass | [aː~ɑː] | [aː~ɑː] | [a] | [ɑː] | |||

| ask, can't | [æ~ɛə] | ||||||

| calf, graph,etc. | [æ] | ||||||

| grant | [æ~ɛə] | ||||||

| father | [ɑː~a] | [ɑ~ɒ] | [ɑː] | [aː~ɑː] | [aː~ɑː] | [ɑː] | |

Trap vowel

| General American | Mid-Atlantic | Received Pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ban | /æn/ | [æ~ɛə~eə][40][41]( |

[æn] | |

| bang | /æŋ/ | [æ̝ŋ-eŋ] | [æŋ] | |

| bag | /æg/ | [æg~æ̝g] | [æg] | |

Unlike modern-day RP, the Mid-Atlantic does not shift the "trap" vowel /æ/ to [a]. Unlike most varieties of American English, in the Mid-Atlantic accent, the trap vowel /æ/ is always pronounced as [æ].[39] and is not raised, and lengthened and/or diphthongized before nasals or other consonants. This means that words like "thanks", or "bank" are pronounced with the same vowel [æ], as in "back". In most dialects of American English, /æ/ is raised, lengthened and/or diphthongized in various environments. The realization of it varies from [æ̝ˑ] to [ɛə] to [eə] to [ɪə], depending on the speaker's regional accent. The most commonly tensed variant of /æ/ throughout North American English is when it appears before nasal consonants (thus, for example, in fan as opposed to fat).

| /æ/ tensing in North American English[54] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | Example words | Dialect | |||||||||||

| Consonant after /æ/ | Syllable type | Canadian, Northwestern, Upper Midwestern USA | Cincinnati (traditional)[55] | Delaware Valley | Eastern New England | General USA & Midland USA | Great Lakes | New York City & New Orleans | Southern USA & African American Vernacular | Western USA | |||

| /r/ | open | arable, arid, baron, barrel, barren, carry, carrot, chariot, charity, clarity, Gary, Harry, Larry, marionette, maritime, marry, marriage, paragon, parent, parish, parody, parrot, etc.; this feature is determined by the presence or absence of the Mary-marry-merry merger |

[ɛ(ə)] | [ɛ(ə)] | [æ] | [ɛ(ə)~æ] | [ɛ(ə)] | [ɛ(ə)] | [æ] | [ɛ(ə)] | [ɛ(ə)] | ||

| /m/, /n/ | closed | Alexander, answer, ant, band, can (the noun), can't, clam, dance, ham, hamburger, hand, handy, man, manly, pants, plan, planning, ranch, sand, slant, tan, understand, etc.; in Philadelphia, began, ran, and swam alone remain lax |

[ɛə~æ] | [eə] | [eə] | [eə~æ] | [eə~æ] | [eə] | [eə] | [ɛ(j)ə~eə] | [eə~æ] | ||

| open | amity, animal, can (the verb), Canada, ceramic, family (varies by speaker),[56], gamut, hammer, janitor, manager, manner, Montana, panel, planet, profanity, salmon, Spanish, etc. |

[æ] | [æ] | ||||||||||

| /g/ | closed | agriculture, bag, crag, drag, flag, magnet, rag, sag, tag, tagging, etc. |

[e~æ] | [æ] | [æ] | [æ] | [eə] | [ɛ(j)ə~æ] | [æ] | ||||

| open | agate, agony, dragon, magazine, ragamuffin, etc. |

[æ] | |||||||||||

| /b/, /d/, /dʒ/, /ʃ/, /v/, /z/, /ʒ/ | closed | absolve, abstain, add, ash, bad, badge, bash, cab, cash, clad, crag, dad, drab, fad, flash, glad, grab, halve (varies by speaker), jazz (varies by speaker), kashmir, mad, magnet, pad, plaid, rag, raspberry, rash, sad, sag, smash, splash, tab, tadpole, trash, etc. In NYC, this environment, particularly, /v/ and /z/, has a lot of variance and many exceptions to the rules. In Philadelphia, bad, mad, and glad alone in this set become tense. Similarly, in New York City, the /dʒ/ set is often tense even in open syllables (magic, imagine, etc.) |

[æ] | [eə] | [ɛə~æ] | [eə] | [ɛə~æ] | ||||||

| /f/, /s/, /θ/ | closed | ask, bask, basket, bath, brass, casket, cast, class, craft, crass, daft, drastic, glass, grass, flask, half, last, laugh, laughter, mask, mast, math, pass, past, path, plastic, task, wrath, etc. |

[eə] | ||||||||||

| all other consonants | act, agony, allergy, apple, aspirin, athlete, avid, back, bat, brat, café, cafeteria, cap, cashew, cat, Catholic, chap, clap, classy, diagonal, fashion, fat, flap, flat, gap, gnat, latch, magazine, mallet, map, mastiff, match, maverick, Max, pack, pal, passive, passion, pat, patch, pattern, rabid, racket, rally, rap, rat, sack, sat, Saturn, savvy, scratch, shack, slack, slap, tackle, talent, trap, travel, wrap, etc. |

[æ] | [æ] | [æ] | |||||||||

Footnotes 1) Nearly all American English speakers pronounce /æŋ/ somewhere between [æŋ] and [eɪŋ], though Western speakers specifically favor [eɪŋ]. 2) The NYC, Philadelphia, and Baltimore dialects' rule of tensing /æ/ in certain closed-syllable environments also applies to words inflectionally derived from those closed-syllable /æ/ environments that now have an open-syllable /æ/. For example, in addition to pass being tense (according to the general rule), so are its open-syllable derivatives passing and passer-by, but not passive. | |||||||||||||

Unlike most dialects of English, the Mid-Atlantic accent does not nasalize vowels before nasal consonants.[39]

/ɛ/ and /ɪ/

Like most American dialects and Received pronunciation, the Mid-Atlantic accent distinguishes the vowels in "pin" and "pen" and thus pronounces /ɛ/ before nasals as [ɛ], and /ɪ/ as [ɪ].

Mary-marry-merry distinction

In the Mid-Atlantic accent, the vowels in "Mary", "marry", and "merry" are all distinct.[39] These three vowel sounds before /ɹ/ are distinguished in British Received Pronunciation and 17% of present-day Americans also distinguish them.[57] On the other hand, General American uses the same vowel [ɛ], in all three words. 57% of all Americans merge all three vowels, and the majority of the rest merge two of them.[57]

| Examples | GA | New York[58] | Mid-Atlantic[39] | RP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mary, compare[42] |

[ɛɹ] | [eɹ~ɛəɹ] | [ɛəɹ] | [ɛ:ɹ~ɛəɹ] |

| marry, comparative, comparison[42] arable, arid, baron, barrel, barren, carry, carrot, chariot, charity, clarity, Gary, Harry, Larry, marionette, maritime, marry, marriage, paragon, parent, parish, parody, parrot, etc.; |

[æɹ] | |||

| merry[42] | [ɛɹ] | |||

| comparable[42] | [ɛɹ], [ə] | [ə] | ||

Vowels before /l/

| General American | Mid-Atlantic | RP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hull | /ʌl/ | [ʌɫ~oʊɫ] | [ʌɫ][59] | [ʌɫ~ɐɫ] |

| holy | /oʊɫ/ | [oʊɫ] | [oʊɫ] | [əʊɫ] |

| wholly | [ɒʊɫ~ɔʊɫ] |

Cure-force distinction

Words in the cure lexical set are pronounced as /ʊr/,[60] as in conservative American and British dialects.

Syllabic consonants

The final syllable in words such as "button" use syllabics [n̩] and [m̩], rather than a schwa or a schwi. Thus button is pronounced as [bʌtʰn̩] rather than [bʌtʰən].[61]

/ɑɹ/ and /ɔɹ/ before a vowel

The Mid-Atlantic accent pronounces /ɑɹV/ and /ɔɹV/ the same as in England and the eastern coastal USA. Most American dialects use [ɑɹ] only in a few words.

| Examples | Canada/some Northern US | California | New York | Boston | Mid-Atlantic | RP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sorry borrow, morrow,

sorry, sorrow, tomorrow |

/ɒr/ | [ɔɹ] | [ɑɹ] | [ɑɹ] | [ɒɹ] | ||

| corridor corridor, euphoric,

foreign, forest, Florida, historic, horrible, majority, minority, moral, orange, Oregon, origin, porridge, priority, quarantine, quarrel, sorority, warranty, warren, warrior (etc.) |

[ɔɹ] | ||||||

| story aura, boring,

choral, coronation, deplorable, flooring, flora, glory, hoary, memorial, menorah, orientation, Moorish, oral, pouring, scorer, storage, story, Tory, warring (etc.) |

/ɔːr/ or /ɔər/ | [ɔɹ] | [ɔɹ] | [ɔːɹ] | |||

Polysyllabic words ending in -ary,-ery,-ory,-mony,-ative,-bury,-berry

| Example | General American | Mid-Atlantic[39] | Received Pronunciation[42] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| secretary | -ary | [ˌɛɹi] | [əɹɪ] | [əɹɪ~əɹi~ɹɪ~ɹi] or [ˌɛɹi] |

| -ery | ||||

| history | -ory | [ˌɔːri] | ||

| Canterbury | -bury | [ˌbɛɹi] | [bəɹɪ] | [bəɹɪ~ˌbɛɹi] |

| testimony | -mony | [ˌmoʊni] | [mənɪ] | [mənɪ~məni] |

| qualitative | -ative | [ˌeɪtɪv] | [ətɪv~ˌeɪtɪv] | [ətɪv~ˌeɪtɪv] |

Lack of /t/ flapping

Unlike North American English dialects, Mid-Atlantic does not pronounce /t/ when it is between vowels as a flap.

T-glottalization and flapping

mountain (glottalized t)

[ˈmæʊnʔn̩] partner (glottalized t)

[ˈpʰɑɹʔnɚ] grateful (glottalized t)

[ˈgɹeɪʔfɫ̩] leader (t-flapping)

[ˈɫiɾɚ] community (t-flapping)

[k(ə)ˈmjunəɾi] party (t-flapping)

[ˈpʰɑɹɾi] |

Cure–force distinction

Mid-Atlantic, like conservative dialects of American English and Received pronunciation, distinguishes the vowels in Cure and Force.[62]

See also

References

- ↑ Drum, Kevin. "Oh, That Old-Timey Movie Accent!" Mother Jones. 2011.

- 1 2 Queen, Robin (2015). Vox Popular: The Surprising Life of Language in the Media. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 241-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 LaBouff, Kathryn (2007). Singing and communicating in English: a singer's guide to English diction. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 0-19-531138-8.

- 1 2 3 Hampton, Marian E. & Barbara Acker (eds.) (1997). The Vocal Vision: Views on Voice. Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 174-77.

- 1 2 Tsai, Michelle (February 28, 2008). "Why Did William F. Buckley Jr. talk like that?". Slate. Retrieved February 28, 2008.

- ↑ Fallows, James (June 7, 2015). "That Weirdo Announcer-Voice Accent: Where It Came From and Why It Went Away. Is your language rhotic? How to find out, and whether you should care". The Atlantic. Washington DC.

- 1 2 "Chapter 7. The Restoration of Post-Vocalic /r/". Web.archive.org. November 18, 2005. Archived from the original on November 18, 2005. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ Konigsberg, Eric (February 29, 2008). "On TV, Buckley Led Urbane Debating Club". The New York Times. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ↑ New York City Accents Changing with the Times. Gothamist (February 25, 2008). Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Jacqueline Kennedy: First Lady of the New Frontier, Barbara A. Perry

- ↑ With Mailer's death, U.S. loses a colorful writer and character – SFGate. Articles.sfgate.com (November 11, 2007). Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ Empress of fashion : a life of Diana Vreeland Los Angeles Public Library Online (December 28, 2012). Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Emily (May 2013). "The First American Anti-Nazi Film, Rediscovered". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ Barbara W. Tuchman (August 31, 2011). Proud Tower. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-307-79811-4. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ Alan M. Wald (1983). The revolutionary imagination: the poetry and politics of John Wheelwright and Sherry Mangan. UNC Press Books. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8078-1535-9. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ A. Javier Treviño (April 2006). George C. Homans: history, theory, and method. Paradigm Publishers. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-59451-191-2. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ↑ Jacob Heilbrunn (January 6, 2009). They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4000-7620-8. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ William Thaddeus Coleman; Donald T. Bliss (October 26, 2010). Counsel for the situation: shaping the law to realize America's promise. Brookings Institution Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8157-0488-1. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ Larry Gelbart; Museum of Television and Radio (New York, N.Y.) (1996). Stand-up comedians on television. Harry N. Abrams Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8109-4467-1. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ Bill Sammon (February 1, 2006). Strategery: How George W. Bush Is Defeating Terrorists, Outwitting Democrats, and Confounding the Mainstream Media. Regnery Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-59698-002-0. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- 1 2 "On Language", by William Safire, The New York Times, January 18, 1987

- ↑ Robert MacNeil; William Cran; Robert McCrum (2005). Do you speak American?: a companion to the PBS television series. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-0-385-51198-8. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ↑ Pearl Harbor speech by Franklin Delano Roosevelt (sound file)

- 1 2 Mufson, Daniel (1994). "The Falling Standard". Theater. 25 (1): 78. doi:10.1215/01610775-25-1-78.

- ↑ Skinner, Monich & Mansell (1990:334)

- 1 2 Kozloff, Sarah (2000). Overhearing Film Dialogue. University of California Press. p. 25.

- ↑ Robert Blumenfeld (December 1, 2002). Accents: A Manual for Actors. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-87910-967-7. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Philip French's screen legends: Cary Grant". The Guardian. London. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ↑ Rawson, Christopher (January 28, 2009). "Lane, Hamlisch among Theater Hall of Fame inductees". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ Fallows, James (August 8, 2011). "Language Mystery: When Did Americans Stop Sounding This Way?". The Atlantic. Washington DC. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ Fletcher, Patricia (February 1, 2013). Classically Speaking. Lulu.com. p. 4. ISBN 9781300594239.

- ↑ Plag, Ingo; Braun, Maria; Lappe, Sabine; Schramm, Mareile (2009). Introduction to English Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-11-021550-2. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- ↑ Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2002). The Phonetics of Dutch and English (PDF) (5 ed.). Leiden/Boston: Brill Publishers. p. 178.

- ↑ Skinner, Monich & Mansell (1990:102)

- ↑ Skinner, Monich & Mansell (1990:336)

- ↑ Wells (1982a:247)

- ↑ Fletcher, Patricia (February 1, 2013). Classically Speaking. Lulu.com. p. 25. ISBN 9781300594239.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Skinner, Edith (January 1, 1990). Speak with Distinction. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 9781557830470.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W.,eds. (January 1, 2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: CD-ROM. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110175325.

- 1 2 Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (January 1, 2006). The Atlas of North American English: Phonetics, Phonology, and Sound Change : a Multimedia Reference Tool. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 187–208. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter; Hartman, James (1991). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521680868.

- ↑ "American Accent Undergoing Great Vowel Shift". NPR.org. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ↑ Fletcher, Patricia (February 1, 2013). Classically Speaking. Lulu.com. p. 145. ISBN 9781300594239.

- 1 2 3 Skinner, Monich & Mansell (1990)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kortmann (2004:263, 264)

- 1 2 Heggarty, Paul et al., eds. (2015). "Accents of English from Around the World". Retrieved September 24, 2016. See under "Std US + ‘up-speak’"

- ↑ Boberg, Charles (2010). The English Language in Canada: Status, History and Comparative Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-139-49144-0.

- ↑ Kortmann (2004:343)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:104)

- ↑ Gimson, A. C. (January 1, 1970). An Introduction to the Pronunciation of English, By A.C. Gimson.

- ↑ "Penny Eckert's Web Page". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ↑ Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (January 1, 2006). The Atlas of North American English: Phonetics, Phonology, and Sound Change : a Multimedia Reference Tool. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110167467.

- ↑ Labov et al. (2006), p. 182.

- ↑ Boberg, Charles; Strassel, Stephanie M. (2000). "in Cincinnati: A change in progress". Journal of English Linguistics. 28: 108–126. doi:10.1177/00754240022004929.

- ↑ Trager, George L. (1940) One Phonemic Entity Becomes Two: The Case of 'Short A' in American Speech: 3rd ed. Vol. 15: Duke UP. 256. Print.

- 1 2 "Dialect Survey Results". www4.uwm.edu. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ↑ Wells, J. C. (April 8, 1982). Accents of English: Volume 3: Beyond the British Isles. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521285414.

- ↑ Fletcher 2013, p. 133.

- ↑ Fletcher, Patricia (February 1, 2013). Classically Speaking. Lulu.com. p. 191. ISBN 9781300594239.

- ↑ Fletcher, Patricia (February 1, 2013). Classically Speaking. Lulu.com. p. 237. ISBN 9781300594239.

- ↑ Fletcher, Patricia (February 1, 2013). Classically Speaking. Lulu.com. p. 192. ISBN 9781300594239.

Further reading

- Robert MacNeil and William Cran, Do You Speak American? (Talese, 2004). ISBN 0-385-51198-1.

- Nosowitz, Dan (October 27, 2016). "How a Fake British Accent Took Old Hollywood by Storm". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- Skinner, Edith; Monich, Timothy; Mansell (ed.), Lilene (1990). Speak with Distinction (Second ed.). New York: Applause Theatre Book Publishers. ISBN 1-55783-047-9.

External links

- Early radio episodes of The Guiding Light featuring Mid-Atlantic English

- The Brian Lehrer Show: Puhfect Together