Translation (biology)

In molecular biology and genetics, translation is the process in which ribosomes in a cell's cytoplasm create proteins, following transcription of DNA to RNA in the cell's nucleus. The entire process is a part of gene expression.

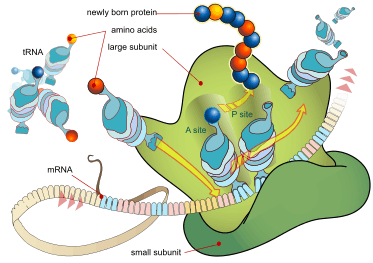

In translation, messenger RNA (mRNA) is decoded by a ribosome, outside the nucleus, to produce a specific amino acid chain, or polypeptide. The polypeptide later folds into an active protein and performs its functions in the cell. The ribosome facilitates decoding by inducing the binding of complementary tRNA anticodon sequences to mRNA codons. The tRNAs carry specific amino acids that are chained together into a polypeptide as the mRNA passes through and is "read" by the ribosome.

Translation proceeds in three phases:

- Initiation: The ribosome assembles around the target mRNA. The first tRNA is attached at the start codon.

- Elongation: The tRNA transfers an amino acid to the tRNA corresponding to the next codon. The ribosome then moves (translocates) to the next mRNA codon to continue the process, creating an amino acid chain.

- Termination: When a stop codon is reached, the ribosome releases the polypeptide.

In bacteria, translation occurs in the cytoplasm, where the large and small subunits of the ribosome bind to the mRNA. In eukaryotes, translation occurs in the cytosol or across the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum in a process called vectorial synthesis. In many instances, the entire ribosome/mRNA complex binds to the outer membrane of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER); the newly created polypeptide is stored inside the ER for later vesicle transport and secretion outside of the cell.

Many types of transcribed RNA, such as transfer RNA, ribosomal RNA, and small nuclear RNA, do not undergo translation into proteins.

A number of antibiotics act by inhibiting translation. These include anisomycin, cycloheximide, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, streptomycin, erythromycin, and puromycin. Prokaryotic ribosomes have a different structure from that of eukaryotic ribosomes, and thus antibiotics can specifically target bacterial infections without any harm to a eukaryotic host's cells.

Basic mechanisms

The basic process of protein production is addition of one amino acid at a time to the end of a protein. This operation is performed by a ribosome.A ribosome is made up of two subunits, a small subunit and a large subunit. these subunits come together before translation of mRNA into a protein for provide a location for translation to be carried out and a polypeptide to be produced. [1] The choice of amino acid type to add is determined by an mRNA molecule. Each amino acid added is matched to a three nucleotide subsequence of the mRNA. For each such triplet possible, the corresponding amino acid is accepted. The successive amino acids added to the chain are matched to successive nucleotide triplets in the mRNA. In this way the sequence of nucleotides in the template mRNA chain determines the sequence of amino acids in the generated amino acid chain.[2] Addition of an amino acid occurs at the C-terminus of the peptide and thus translation is said to be amino-to-carboxyl directed.[3]

The mRNA carries genetic information encoded as a ribonucleotide sequence from the chromosomes to the ribosomes. The ribonucleotides are "read" by translational machinery in a sequence of nucleotide triplets called codons. Each of those triplets codes for a specific amino acid.

The ribosome molecules translate this code to a specific sequence of amino acids. The ribosome is a multisubunit structure containing rRNA and proteins. It is the "factory" where amino acids are assembled into proteins. tRNAs are small noncoding RNA chains (74-93 nucleotides) that transport amino acids to the ribosome. tRNAs have a site for amino acid attachment, and a site called an anticodon. The anticodon is an RNA triplet complementary to the mRNA triplet that codes for their cargo amino acid.

Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases (enzymes) catalyze the bonding between specific tRNAs and the amino acids that their anticodon sequences call for. The product of this reaction is an aminoacyl-tRNA. This aminoacyl-tRNA is carried to the ribosome by EF-Tu, where mRNA codons are matched through complementary base pairing to specific tRNA anticodons. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases that mispair tRNAs with the wrong amino acids can produce mischarged aminoacyl-tRNAs, which can result in inappropriate amino acids at the respective position in protein. This "mistranslation"[4] of the genetic code naturally occurs at low levels in most organisms, but certain cellular environments cause an increase in permissive mRNA decoding, sometimes to the benefit of the cell.

The ribosome has three sites for tRNA to bind. They are the aminoacyl site (abbreviated A), the peptidyl site (abbreviated P) and the exit site (abbreviated E). With respect to the mRNA, the three sites are oriented 5’ to 3’ E-P-A, because ribosomes move toward the 3' end of mRNA. The A site binds the incoming tRNA with the complementary codon on the mRNA. The P site holds the tRNA with the growing polypeptide chain. The E site holds the tRNA without its amino acid. When an aminoacyl-tRNA initially binds to its corresponding codon on the mRNA, it is in the A site. Then, a peptide bond forms between the amino acid of the tRNA in the A site and the amino acid of the charged tRNA in the P site. The growing polypeptide chain is transferred to the tRNA in the A site. Translocation occurs, moving the tRNA in the P site, now without an amino acid, to the E site; the tRNA that was in the A site, now charged with the polypeptide chain, is moved to the P site. The tRNA in the E site leaves and another aminoacyl-tRNA enters the A site to repeat the process.[5]

After the new amino acid is added to the chain, and after the mRNA is released out of the nucleus and into the ribosome's core, the energy provided by the hydrolysis of a GTP bound to the translocase EF-G (in prokaryotes) and eEF-2 (in eukaryotes) moves the ribosome down one codon towards the 3' end. The energy required for translation of proteins is significant. For a protein containing n amino acids, the number of high-energy phosphate bonds required to translate it is 4n-1 . The rate of translation varies; it is significantly higher in prokaryotic cells (up to 17-21 amino acid residues per second) than in eukaryotic cells (up to 6-9 amino acid residues per second).[6]

In activation, the correct amino acid is covalently bonded to the correct transfer RNA (tRNA). The amino acid is joined by its carboxyl group to the 3' OH of the tRNA by an ester bond. When the tRNA has an amino acid linked to it, it is termed "charged". Initiation involves the small subunit of the ribosome binding to the 5' end of mRNA with the help of initiation factors (IF). Termination of the polypeptide happens when the A site of the ribosome faces a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA). No tRNA can recognize or bind to this codon. Instead, the stop codon induces the binding of a release factor protein that prompts the disassembly of the entire ribosome/mRNA complex.

The process of translation is highly regulated in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms. Regulation of translation can impact the global rate of protein synthesis which is closely coupled to the metabolic and proliferative state of a cell. In addition, recent work has revealed that genetic differences and their subsequent expression as mRNAs can also impact translation rate in an RNA-specific manner.[7]

Genetic code

Whereas other aspects such as the 3D structure, called tertiary structure, of protein can only be predicted using sophisticated algorithms, the amino acid sequence, called primary structure, can be determined solely from the nucleic acid sequence with the aid of a translation table.

This approach may not give the correct amino acid composition of the protein, in particular if unconventional amino acids such as selenocysteine are incorporated into the protein, which is coded for by a conventional stop codon in combination with a downstream hairpin (SElenoCysteine Insertion Sequence, or SECIS).

There are many computer programs capable of translating a DNA/RNA sequence into a protein sequence. Normally this is performed using the Standard Genetic Code, however, few programs can handle all the "special" cases, such as the use of the alternative initiation codons. For instance, the rare alternative start codon CTG codes for Methionine when used as a start codon, and for Leucine in all other positions.

Example: Condensed translation table for the Standard Genetic Code (from the NCBI Taxonomy webpage).

AAs = FFLLSSSSYY**CC*WLLLLPPPPHHQQRRRRIIIMTTTTNNKKSSRRVVVVAAAADDEEGGGG Starts = ---M---------------M---------------M---------------------------- Base1 = TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG Base2 = TTTTCCCCAAAAGGGGTTTTCCCCAAAAGGGGTTTTCCCCAAAAGGGGTTTTCCCCAAAAGGGG Base3 = TCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAG

Translation tables

Even when working with ordinary eukaryotic sequences such as the Yeast genome, it is often desired to be able to use alternative translation tables—namely for translation of the mitochondrial genes. Currently the following translation tables are defined by the NCBI Taxonomy Group for the translation of the sequences in GenBank:

- The Standard

- The Vertebrate Mitochondrial Code

- The Yeast Mitochondrial Code

- The Mold, Protozoan, and Coelenterate Mitochondrial Code and the Mycoplasma/Spiroplasma Code

- The Invertebrate Mitochondrial Code

- The Ciliate, Dasycladacean and Hexamita Nuclear Code

- The Echinoderm and Flatworm Mitochondrial Code

- The Euplotid Nuclear Code

- The Bacterial and Plant Plastid Code

- The Alternative Yeast Nuclear Code

- The Ascidian Mitochondrial Code

- The Alternative Flatworm Mitochondrial Code

- Blepharisma Nuclear Code

- Chlorophycean Mitochondrial Code

- Trematode Mitochondrial Code

- Scenedesmus obliquus mitochondrial Code

- Thraustochytrium Mitochondrial Code

See also

References

- ↑ Biology. McGraw hill education. p. 249. ISBN 978-981-4581-85-1.

- ↑ Neill C (1996). Biology (Fourth ed.). The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company. p. 309–310. ISBN 0-8053-1940-9.

- ↑ Stryer L (2002). Biochemistry (Fifth ed.). W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 826. ISBN 0-7167-4684-0.

- ↑ Moghal A, Mohler K, Ibba M (November 2014). "Mistranslation of the genetic code". FEBS Letters. 588 (23): 4305–10. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.08.035. PMID 25220850.

- ↑ Griffiths A (2008). "9". Introduction to Genetic Analysis (9th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 335–339. ISBN 978-0-7167-6887-6.

- ↑ Ross JF, Orlowski M (February 1982). "Growth-rate-dependent adjustment of ribosome function in chemostat-grown cells of the fungus Mucor racemosus". Journal of Bacteriology. 149 (2): 650–3. PMC 216554

. PMID 6799491.

. PMID 6799491. - ↑ Cenik C, Cenik ES, Byeon GW, Grubert F, Candille SI, Spacek D, Alsallakh B, Tilgner H, Araya CL, Tang H, Ricci E, Snyder MP (November 2015). "Integrative analysis of RNA, translation, and protein levels reveals distinct regulatory variation across humans". Genome Research. 25 (11): 1610–21. doi:10.1101/gr.193342.115. PMID 26297486.

Further reading

- Champe PC, Harvey RA, Ferrier DR (2004). Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews: Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-2265-9.

- Cox M, Nelson DR, Lehninger AL (2005). Lehninger principles of biochemistry (4th ed.). San Francisco...: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- Malys N, McCarthy JE (March 2011). "Translation initiation: variations in the mechanism can be anticipated". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 68 (6): 991–1003. doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0588-z. PMID 21076851.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Translation (biology). |

- Virtual Cell Animation Collection: Introducing Translation

- Translate tool (from DNA or RNA sequence)