Trisomy 16

Trisomy 16 is a chromosomal abnormality in which there are 3 copies of chromosome 16 rather than two.[1] It is the most common trisomy leading to miscarriage and the second most common chromosomal cause of it, closely following X-chromosome monosomy.[2] If so like most chromosomal abnormalities, trisomy 16 usually causes miscarriage in the first trimester of pregnancy.

It is not possible for a child to be born alive with an extra copy of this chromosome present in all cells (full trisomy 16).[3] It is possible, however, for a child to be born alive with the mosaic form.[4][5]

Chromosome 16

Normally humans have 2 copies of chromosome 16, one inherited by each parent. This chromosome represents almost 3% of all DNA in cells.[6]

Screening

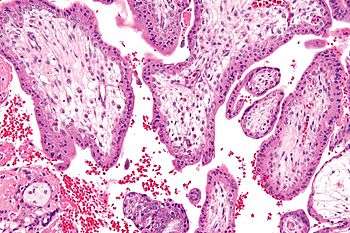

During pregnancy, women can be screened by chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis to detect trisomy 16. This can cause fetal growth retardation.[7]

Full trisomy 16

Full trisomy 16 is incompatible with life and most of the time it results in miscarriage during the first trimester. This occurs when all of the cells in the body contain an extra copy of chromosome 16.[7]

Mosaic trisomy 16

Mosaic trisomy 16, a rare chromosomal disorder, is compatible with life, therefore a baby can be born alive. This happens when only some of the cells in the body contain the extra copy of chromosome 16. Some of the consequences include slow growth before birth.[8]

Prenatal diagnosis

During prenatal diagnosis the levels of trisomy in fetal-placental tissues can be analyzed. These levels can be predictors of outcomes in mosaic trisomy 16 pregnancies. In a study of prenatal diagnosis cases, there were 66% live births with an average 35.7 weeks gestational age. About 45% of them had malformations. The most common malformations were CSD, ASD, and hypospadias.[6] However, trisomy 16 does not always result in anatomical abnormalities.[8]

References

- ↑ Mary Kugler, R.N. (2005-08-20). "Chromosome 16 Disorders". About.com:Rare Diseases. About, Inc. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ↑ DeCherney, Alan H.; Nathan, Lauren; Goodwin, T. Murphy; Laufer, Neri, eds. (2007). Current diagnosis & treatment: Obstetrics & gynecology (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-143900-8.

- ↑ Seller, MJ; Fear, C; Kumar, A; Mohammed, S (2004). "Trisomy 16 in a mid-trimester IVF foetus with multiple abnormalities". Clinical Dysmorphology. London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 13 (3): 187–190. doi:10.1097/01.mcd.0000133498.91871.1b. ISSN 0962-8827. OCLC 196772467. PMID 15194958. BL Shelfmark 3286.273700.

- ↑ Simensen, RJ; Colby, RS; Corning, KJ (2003). "A prenatal counseling conundrum: mosaic trisomy 16. A case study presenting cognitive functioning and adaptive behavior". Genetic Counselling. Geneva: Édition médicine et hygiène. 14 (3): 331–6. ISSN 1015-8146. OCLC 210520912. PMID 14577678. BL Shelfmark 4111.845000.

- ↑ Langlois S, Yong PJ, Yong SL; Yong, P J; Yong, S L; Barrett, I; Kalousek, D K; Miny, P; Exeler, R; Morris, K; Robinson, W P; et al. (2006). "Postnatal follow-up of prenatally diagnosed trisomy 16 mosaicism". Prenatal Diagnosis. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 26 (6): 548–558. doi:10.1002/pd.1457. OCLC 108807898. PMID 16683298. BL Shelfmark 6607.646000.

- 1 2 Yong, PJ; Barrett, IJ; Kalousek, DK; Robinson, WP (2003). "Clinical aspects, prenatal diagnosis, and pathogenesis of trisomy 16 mosaicism". Journal of Medical Genetics. 40 (3): 175–82. doi:10.1136/jmg.40.3.175. PMC 1735382

. PMID 12624135.

. PMID 12624135. - 1 2 Groli, C; Cerri, V; Tarantini, M; Bellotti, D; Jacobello, C; Gianello, R; Zanini, R; Lancetti, S; Zaglio, S (1996). "Maternal serum screening and trisomy 16 confined to the placenta". Prenatal diagnosis. 16 (8): 685–9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199608)16:8<685::AID-PD907>3.0.CO;2-2. PMID 8878276.

- 1 2 Kontomanolis, EN; Lambropoulou, M; Georgiadis, A; Gramatikopoulou, I; Deftereou, TH; Galazios, G (2012). "The challenging trisomy 16: A case report". Clinical and experimental obstetrics & gynecology. 39 (3): 412–3. PMID 23157062.