Mexico–United States relations

|

|

Mexico |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| Embassy of Mexico, Washington, D.C. | Embassy of the United States, Mexico City |

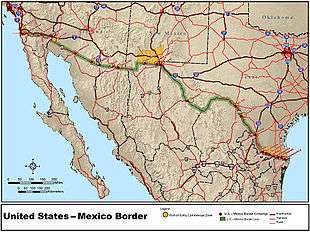

Mexico–United States relations refers to the foreign relations between the United Mexican States (Estados Unidos Mexicanos) and the United States of America. The two countries share a maritime and land border in North America. Several treaties have been concluded between the two nations bilaterally, such as the Gadsden Purchase, and multilaterally, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement. Both are members of various international organizations, including the Organization of American States and the United Nations.

Since the late nineteenth century during the regime of President Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911), the two countries have had close diplomatic and economic ties. During Díaz's long presidency, Mexico was opened to foreign investment and U.S. entrepreneurs invested in ranching and agricultural enterprises and mining. The U.S. played an important role in the course of the Mexican Revolution (1910–20) with direct actions of the U.S. government in supporting or repudiating support of revolutionary factions.

The long border between the two countries means that peace and security in that region is important to the U.S.'s national security and international trade. The U.S. is Mexico's biggest trading partner and Mexico is the U.S.'s third largest trading partners. In 2010, Mexico's exports totaled US$309.6 billion, and almost three quarters of those purchases were made by the United States.[1] They are also closely connected demographically, with over one million U.S. citizens living in Mexico and Mexico being the largest source of immigrants to the United States. Undocumented immigration and illegal trade in drugs and in fire arms have been causes of differences between the two governments but also of cooperation.

While condemning the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and providing considerable relief aid to the U.S. after Hurricane Katrina, the Mexican government, pursuing neutrality in international affairs, opted not to actively join the controversial War on Terror and the even more controversial Iraq War, instead being the first nation in history to formally and voluntarily leave the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance in 2002,[2] though Mexico later joined the U.S. in supporting military intervention in the Libyan Civil War.[3]

According to a 2010 Gallup poll, 4.4% of surveyed Mexicans, roughly 6.2 million people, say that they would move permanently to the United States if given the chance,[4] and according to the 2012 U.S. Global Leadership Report, 37% of Mexicans approve of U.S. leadership, with 27% disapproving and 36% uncertain.[5] As of 2013, Mexican students form the 9th largest group of international students studying in the United States, representing 1.7% of all foreigners pursuing higher education in the U.S.[6]

History

The United States of America shares a unique and often complex relationship with the United Mexican States. With shared history stemming back to the Texas Revolution (1835–1836) and the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), several treaties have been concluded between the two nations, most notably the Gadsden Purchase, and multilaterally with Canada, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Mexico and the United States are members of various international organizations, such as the Organization of American States and the United Nations. Boundary disputes and allocation of boundary waters have been administered since 1889 by the International Boundary and Water Commission, which also maintains international dams and wastewater sanitation facilities. Once viewed as a model of international cooperation, in recent decades the IBWC has been heavily criticized as an institutional anachronism, by-passed by modern social, environmental and political issues.[7] Illegal immigration, arms sales, and drug smuggling continue to be contending issues in 21st-century U.S.-Mexico relations.

Early history

U.S.–Mexico relations grew out of the earlier relations between the fledgling nation of the United States and the Spanish Empire and its viceroyalty of New Spain. Modern Mexico formed the core area of the Viceroyalty of New Spain at the time the United States gained independence from Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). Spain had served as an ally to the American colonists in that war.

The aspect of Spanish-American relations that would bear most prominently on later relations between the U.S. and Mexico was the ownership of Texas. In the early 19th century the United States claimed that Texas was part of the territory of Louisiana, and therefore had been rightfully acquired by the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803. The Spanish, however, claimed it was not, as the western boundaries of Louisiana were not clearly defined.[8] In 1819 the dispute was resolved with the signing of the Adams–Onís Treaty, in which the United States relinquished its claims to Texas and instead purchased Spanish Florida.[9]

In 1821 New Spain gained its independence from Spain and established the First Mexican Empire under the rule of Agustín de Iturbide, who had initially fought in the royal army against the insurgents in the independence from Spain. Independent Mexico was soon recognized by the United States.[10] The two countries quickly established diplomatic relations, with Joel Poinsett as the first envoy.[11] In 1828 Mexico and the United States confirmed the boundaries established by the Adams–Onís Treaty by concluding the Treaty of Limits, but certain elements in the United States were greatly displeased with the treaty, as it relinquished rights to Texas.[12] Texas remained a focal point of U.S-Mexico relations for decades. The relationship was further affected by internal struggles within the two countries: in Mexico these included concerns over the establishment of a centralized government, while in the United States it centered around the debate over the expansion of slavery, which was expanded to the Mexican territory of Texas.[12]

Beginning in the 1820s, Americans led by Stephan F. Austin and other non-Mexicans began to settle in eastern Texas in large numbers. These white settlers, known as Texians, were frequently at odds with the Mexican government, since they sought autonomy from the central Mexican government and the expansion of black slavery into Mexico, which had abolished the institution in 1829 under Mexican president Vicente Guerrero. Their disagreements led to the Texas Revolution, one of a series of independence movements that came to the fore following the 1835 amendments to the Constitution of Mexico, which substantially altered the governance of the country. Prior to the Texas Revolution the general public of the United States was indifferent to Texas, but afterward, public opinion was increasingly sympathetic to the Texans.[13] Following the war a Republic of Texas was declared, though independence was not recognized by Mexico, and the boundaries between the two were never agreed upon. In 1845 the United States annexed Texas, leading to a major border dispute and eventually to the Mexican–American War.

Mexican–American War (1846–48)

The Mexican–American War was fought from 1846 to 1848. Mexico refused to acknowledge that its runaway province of Texas had achieved independence and warned that annexation to the United States would mean war. The United States annexed Texas in late 1845. The war began the next spring.[14] U.S. President James K. Polk encouraged Congress to declare war following a number of skirmishes on the Mexican-American border. [15][16] The war proved disastrous for Mexico; the Americans seized New Mexico and California and invaded Mexico's northern provinces. In September 1847, U.S. troops under General Winfield Scott captured Mexico City.[17] The war ended in a decisive U.S. victory; the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the conflict. As a result, Mexico was forced to sell all of its northernmost territory, including California and New Mexico, to the United States in the Mexican Cession. Additionally, Mexico relinquished its claims to Texas, and the United States forgave Mexico's debts to U.S. citizens. Mexicans in the annexed areas became full U.S. citizens.[18]

There had been much talk early in the war about annexing all of Mexico, primarily to enlarge the areas open to slavery. However many Southern political leaders were in the invasion armies and they recommended against total annexation because of the differences in political culture between the United States and Mexico.[19]

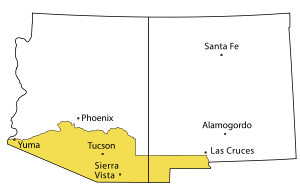

In 1854 the United States purchased an additional 30,000 square miles of desert land from Mexico in the Gadsden Purchase; the price was $10 million. The goal was to build a rail line through southern Arizona to California.[20]

1850s

Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna sold Mexican territory to the United States in which is known as the Gadsden Purchase, allowing the U.S. to build a railway line more easily through that region. That purchase played a significant role in the ouster of Santa Anna by Mexican liberals, in what is known as the Revolution of Ayutla, since it was widely viewed as selling Mexico's patrimony.

As the liberals made significant political changes in Mexico and a civil war broke out between conservative opponents to the liberal reform, the liberal government of Benito Juárez negotiated with the U.S. to enable the building of an interoceanic route in southern Mexico. A treaty was concluded in 1859 between Melchor Ocampo and the U.S. representative Robert Milligan McLane, giving their names to the McLane-Ocampo Treaty. The U.S. Senate failed to ratify the treaty. Had it passed, Mexico would have made significant concessions to the U.S. in exchange for cash desperately needed by the liberal Mexican government.

1860s

In 1861, Mexican conservatives looked to French leader Napoleon III to abolish the Republic led by liberal President Benito Juárez. France favored the secessionist Southern states that formed the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War, but did not accord it diplomatic recognition. The French expected that a Confederate victory would facilitate French economic dominance in Mexico. Realizing the U.S. government could not intervene in Mexico, France invaded Mexico and installed an Austrian prince Maximilian I of Mexico as its puppet ruler in 1864. Owing to the shared convictions of the democratically-elected government of Juárez and U.S. President Lincoln, Matías Romero, Juárez's minister to Washington, mobilized support in the U.S. Congress and the U.S. protested France's violation of the Monroe Doctrine. Once the American Civil War came to a close in April 1865, the U.S. allowed supporters of Juárez to openly purchase weapons and ammunition and issued stronger warnings to Paris. Napoleon III ultimately withdrew his army in disgrace, and Emperor Maximilian, who remained in Mexico even when given the choice of exile, was executed by the Mexican government in 1867.[21] The support that the U.S. had accorded the liberal government of Juárez, by refusing to recognize the government of Maximilian and then by supplying arms to liberal forces, helped improve the U.S.–Mexican relationship.

At war's end numerous Confederates fled to exile in Mexico. Many eventually returned to the U.S.[22][23][24]

The Porfiriato (1876–1910)

With general Porfirio Díaz's seizure of the presidency in 1876, relations between Mexico and foreign powers, including the United States changed. It became more welcoming to foreign investment in order to reap economic gain, but it would not relinquish its political sovereignty.[25] Díaz's regime aimed to implement "order and progress," which reassured foreign investors that their enterprises could flourish. Díaz was a nationalist and a military hero who had fought ably against the French Intervention (1862–67). The U.S. had aided the liberal government of Benito Juárez by not recognizing the French invaders and the puppet emperor that Mexican conservatives invited to rule over them, and the U.S. had also provided arms to the liberals once its own civil war was over. But Díaz was wary of the "colossus of the north"[26] and the phrase "Poor Mexico! So far from God, so close to the United States" (Pobre México: tan lejos de Dios y tan cerca de los Estados Unidos) is attributed to him.[27]

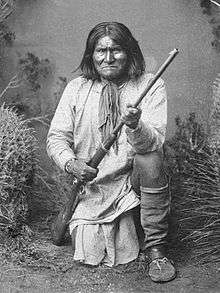

Díaz had ousted president Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada in the Revolution of Tuxtepec (1876). The U.S. did not recognize the Díaz government until 1878, when Rutherford B. Hayes was president. Given that France had invaded Mexico in 1862, Mexico did not initially restore diplomatic relations with it or other European powers, but did pursue a "special relationship" with the United States.[28] One issue causing tension between Mexico and the U.S. were indigenous groups whose traditional territories straddled what was now an international boundary, most notably the Apache tribe. The Apache leader Geronimo became infamous for his raids on both sides of the border. Bandits operating in both countries also frequently crossed the border to raid Mexican and American settlements, taking advantage of mutual distrust and the differing legal codes of both nations.[29] These threats eventually spurred increased cooperation between American and Mexican authorities, especially when concerning mounted cavalry forces.[30] Tensions between the U.S. and Mexico remained high, but a combination of factors in the U.S. brought about recognition of the Díaz regime. These included the need to distract the U.S. electorate from the scandal of the 1876 election by focusing on the international conflict with Mexico as well as the desire of U.S. investors and their supporters in Congress to build a railway line between Mexico City and El Paso, Texas.[31]

With the construction of the railway line linking Mexico and the United States, the border region developed from a sparsely populated frontier region into a vibrant economic zone. The construction of the railway and collaboration of the United States and Mexican armies effectively ended the Apache Wars in the late 1880s. The line between Mexico City and El Paso, Texas was inaugurated in 1884.[32]

An ongoing issue in the border region was the exact boundary between Mexico and the U.S., particularly because the channel of the Rio Grande shifted at intervals. In 1889, the International Boundary and Water Commission was established, and still functions in the twenty-first century.

The Taft–Díaz summit

In 1909, William Howard Taft and Porfirio Díaz planned a summit in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, an historic first meeting between a U.S. and a Mexican president, the first time an American president would cross the border into Mexico, and only the second international trip by a sitting president (Theodore Roosevelt had traveled to Panama while president).[33] Diaz requested the meeting to show U.S. support for his planned eighth run as president, and Taft agreed to support Diaz in order to protect the several billion dollars of American capital then invested in Mexico.[34] Both sides agreed that the disputed Chamizal strip connecting El Paso to Ciudad Juárez would be considered neutral territory with no flags present during the summit, but the meeting focused attention on this territory and resulted in assassination threats and other serious security concerns.[35] The Texas Rangers, 4,000 U.S. and Mexican troops, U.S. Secret Service agents, BOI agents (later FBI) and U.S. marshals were all called in to provide security.[36] An additional 250 private security detail led by Frederick Russell Burnham, the celebrated scout, was hired by John Hays Hammond, a close friend of Taft from Yale and a former candidate for U.S. Vice-President in 1908 who, along with his business partner Burnham, held considerable mining interests in Mexico.[37][38][39] On October 16, the day of the summit, Burnham and Private C.R. Moore, a Texas Ranger, discovered a man holding a concealed palm pistol standing at the El Paso Chamber of Commerce building along the procession route.[40] Burnham and Moore captured and disarmed the assassin within only a few feet of Taft and Díaz.[41]

The Mexican Revolution

The United States had long recognized the government of Porfirio Díaz. The U.S. also supported the transition that brought about the democratic election of Francisco I. Madero. Wilson, who took office shortly after Madero's assassination in 1913, rejected the legitimacy of Huerta's "government of butchers" and demanded in Mexico hold democratic elections.[42] After U.S. navy personnel were arrested in the port of Tampico by Huerta's soldiers, the U.S. seized Veracruz, resulting in the death of 170 Mexican soldiers and an unknown number of Mexican civilians.

Americans. Wilson sent a punitive expedition led by General John J. Pershing deep into Mexico; it deprived the rebels of supplies but failed to capture Villa.

Meanwhile, Germany was trying to divert American attention from Europe by sparking a war. It sent Mexico the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917, offering a military alliance to fight the U.S. The British intercepted the message and Wilson released it to the press, escalating demands for American entry into the European War. The Mexican government rejected the proposal, in no small part due to a contract to provide the Royal Navy with oil. [43][44]

1920–1945

Following the end of the military phase of the Mexican Revolution, there were claims by Americans and Mexicans for damage during the decade-long civil war. The American-Mexican Claims Commission was set up to resolve them during the presidency of revolutionary general Alvaro Obregón and U.S president Calvin Coolidge. Obregón was eager to resolve issues with the U.S., including petroleum, in order to secure diplomatic recognition from the U.S. Negotiations over oil resulted in the Bucareli Treaty in 1923.

When revolutionary general Plutarco Elías Calles succeeded Obregón in 1924, he repudiated the Bucareli Treaty. Relations between the Calles government and the U.S. deteriorated further. In 1926, Calles implemented articles of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 that gave the state the power to suppress the role of the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico. A major civil uprising broke out, known as the Cristero War. The turmoil in Mexico prompted the U.S. government to replace its ambassador, appointing a Wall Street banker, Dwight W. Morrow to the post. Morrow played a key role in brokering an agreement between the Roman Catholic hierarchy and the Mexican government which ended the conflict in 1929. Morrow created a great deal of good will in Mexico by replacing the sign at the embassy to read "Embassy of the United States of America" rather than "American Embassy." He also commissioned Diego Rivera to paint murals at the palace of Hernán Cortés in Cuernavaca, Morelos, that depicted Mexican history.

During the presidency of revolutionary general Lázaro Cárdenas del Río, the controversy over petroleum again flared. Standard Oil had major investments in Mexico and a dispute between the oil workers and the company was to be resolved via the Mexican court system. The dispute, however, escalated, and on March 18, 1938, President Cárdenas used constitutional powers to expropriate foreign oil interests in Mexico and created the government-owned Petroleos Mexicanos or PEMEX. Although the United States had had a long history of interventions in Latin America, the expropriation did not result in that. U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was implementing the Good Neighbor Policy, in which the U.S. eschewed the role of intervention and courted better relations with the region, which would be vital if another major conflict broke out in Europe. However, with the Great Depression, the United States implemented a program of expelling Mexicans from the U.S. in what was known as Mexican Repatriation.

When the U.S. did enter World War II, it negotiated an agreement with Mexican President Manuel Avila Camacho to be allies in the conflict against the Axis powers. The U.S. bought Mexican metals, especially copper and silver, but also importantly implemented a labor agreement with Mexico, known as the Bracero Program. Mexican agricultural workers were brought under contract to the U.S. to do mainly agricultural labor as well as harvesting timber in the northwest. The program continued in effect until 1964 when organized labor in the U.S. pushed for ending it.

Since 1945

The alliance between Mexico and the U.S. during World War II brought the two countries into a far more harmonious relationship with one another. Mexican President Manuel Avila Camacho met in person with both Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, helping to cement ties with the U.S. Avila Camacho was not a leader in the Mexican Revolution himself, and held opinions that were pro-business and pro-religious that were more congenial to the U.S. while he maintained revolutionary rhetoric. During Avila Camacho's visit with Truman near the centenary of the Mexican–American War, Truman returned some of the Mexican banners captured by the United States in the conflict and praised the military cadets who died defending Mexico City during the invasion.[45]

For bilateral relations between the U.S. and Mexico, the end of World War II meant decreased U.S. demand for Mexican labor via the guest-worker Bracero Program and for Mexican raw materials to fuel a major war. For Mexican laborers and Mexican exporters, there were fewer economic opportunities. However, while at the same time the government's coffers were full and aided post-war industrialization.[46] In 1946, the dominant political party changed its name to the Institutional Revolutionary Party, and while maintaining revolutionary rhetoric, in fact embarked on industrialization that straddled the line between nationalist and pro-business policies. Mexico supported U.S. policies in the Cold War and did not challenge U.S. intervention in Guatemala that ousted leftist president Jacobo Arbenz.[47]

Boundary issues and the border region

Under Mexican president Adolfo López Mateos, the U.S. and Mexico concluded a treaty to resolve the Chamizal dispute over the boundary between the two countries, with the U.S. ceding the disputed territory.[48] The Boundary Treaty of 1970 resolved further issues between the two countries.

North American Free Trade Agreement 1994-

The United States and Mexico have close economic ties. The US is Mexico's largest trading partner, accounting for close to half of all exports in 2008 and more than half of all imports in 2009. For the US, Mexico is the third largest trading partner after Canada and China as of June 2010.[49] The two countries and Canada have signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 with the goal of eliminating barriers to trade and investment. Foreign direct investment (FDI) into Mexico has risen dramatically since NAFTA went into effect and in 2008, 41% of all FDI came from U.S. sources. Roughly half of this investment goes to manufacturing. One U.S. company, Wal-Mart, is the largest private sector employer in Mexico.[50]

Undocumented immigrants

As of 2009, 62% of undocumented immigrants in the United States originate from Mexico.[51] Commonly those who enter the United States illegally are smuggled in by individuals referred to as "coyotes".[52] In 2005, according to the World Bank, Mexico received $18.1 billion USD in remittances from individuals in the United States.[53] In response to this and the trafficking of illegal drugs the United States has built a barrier on its border with Mexico.[54]

Trade of illegal drugs

Mexico is a major source of drugs entering the United States. By the 1990s, 80%-90% of the cocaine smuggled into the United States arrived through Mexico. In February 1985, US Drug Enforcement Administration agent Enrique Camarena, nicknamed "Kiki", was kidnapped in Mexico, tortured and then murdered, in what was seen as an attempt by the Mexican drug cartels to intimidate the United States. After one-party rule ended in Mexico in 2000, the Mexican government increased its efforts to combat the all-powerful drug cartels. The United States sent aid to Mexico for this purpose through the Merida Initiative. As of November 2009, the U.S. has delivered about $214 million of the pledged $1.6 billion.[55]

Diplomatic vehicle shooting

On the 24th of August 2012, a United States embassy vehicle was fired upon by Mexican Federal Police agents, causing two individuals to be wounded.[56] The incident occurred south of Mexico City, while the vehicle had two Americans and a Mexican Navy captain who were traveling to a Mexican naval installation; the area where the shooting occurred is close to Cuernavaca, which is inflicted by several criminal organizations.[57] Twelve Mexican Federal Police agents were arrested for the shooting.[58] The two Americans were later reported to be CIA agents, who were investigating a kidnapping.[59] In early October 2012, there was strong evidence that the two CIA agents were victims of a targeted assassination attempt, as the Mexican Federal Police agents may have been working for the Beltran Leyva Cartel; however, it is one of several lines of investigation being conducted by Mexican officials.[60]

Gallery

-

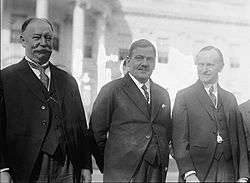

Former U.S. President William Taft, Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles, and U.S. President Calvin Coolidge at the White House.

-

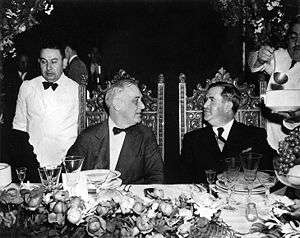

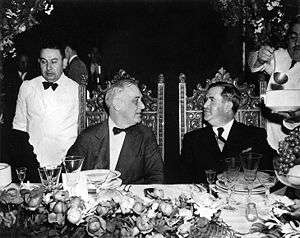

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt having dinner with Mexican President Manuel Ávila Camacho in Monterrey.

-

U.S. Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Baines Johnson and former U.S. President Harry S. Truman having dinner with Mexican President Adolfo López Mateos in 1959.

-

U.S. President Richard Nixon riding a presidential motorcade in San Diego with Mexican President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz.

-

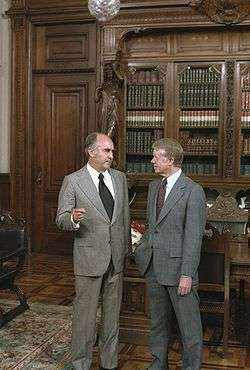

Mexican President José López Portillo and U.S. President Jimmy Carter during a welcoming ceremony in Mexico City, 1979.

-

Mexican President Miguel de la Madrid and U.S. President Ronald Reagan in Mazatlán, 1988.

-

From left to right: U.S. President Ronald Reagan, his wife Nancy, Mexican President Miguel de la Madrid and his wife Paloma Cordero in Cross Hall, White House, during a state dinner.

-

U.S. First Lady Laura Bush, U.S. President George W. Bush, Mexican First Lady Marta Sahagún, and Mexican president Vicente Fox in Crawford, Texas, 2004.

-

U.S. President Barack Obama and Mexican President Felipe Calderón in Mexico City, 2009.

-

President Barack Obama and President-Elect Enrique Peña Nieto meet at the White House following Peña Nieto's election victory.

Diplomatic missions

|

|

Common memberships

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

- Bank for International Settlements

- Food and Agriculture Organization

- G-20

- International Atomic Energy Agency

- International Chamber of Commerce

- International Court of Justice

- International Olympic Committee

- International Monetary Fund

- International Telecommunication Union

- Interpol

- North American Free Trade Agreement

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- Organization of American States

- Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America

- UNESCO

- United Nations

- World Bank

- World Health Organization

- World Trade Organization

See also

- American Mexican

- Embassy of Mexico in Washington DC

- International child abduction in Mexico

- Mexican American

- Mexico–United States border

- Mexico–United States barrier

- United States Border Patrol interior checkpoints

- United States presidential visits to Mexico

References

- ↑ "Mexico, the U.S. and Indiana: Economy and Trade -". InContext.indiana.edu. 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- ↑ OEA: México abandona el TIAR BBC

- ↑ Mexico condemns repression in Libya Two Circles

- ↑ Roughly 6.2 Million Mexicans Express Desire to Move to U.S. Gallup

- ↑ U.S. Global Leadership Project Report - 2012 Gallup

- ↑ Top 25 Places of Origin of International Students Institute of International Education

- ↑ Robert J. McCarthy, Executive Authority, Adaptive Treaty Interpretation, and the International Boundary and Water Commission, U.S.-Mexico, 14-2 U. Denv. Water L. Rev. 197(Spring 2011) (also available for free download at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1839903).

- ↑ Rives, pp. 1–2; 11–13.

- ↑ Rives, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Rives, p. 45.

- ↑ Rives, p. 38, 45–46.

- 1 2 Rives, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Rives, pp. 262–264.

- ↑ David M. Pletcher, The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War (1973).

- ↑ "Mexican-American War - Facts & Summary - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ↑ Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848, at 741 (2007).

- ↑ Timothy J. Henderson, A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and Its War with the United States (2007).

- ↑ Jesse S. Reeves, "The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo," American Historical Review, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Jan., 1905), pp. 309–324 in JSTOR.

- ↑ Mike Dunning, "Manifest Destiny and the Trans-Mississippi South: Natural Laws and the Extension of Slavery into Mexico," Journal of Popular Culture (2001) 35#2 111–127.

- ↑ Ray Allen Billington; Martin Ridge (2001). Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier. U, of New Mexico Press. p. 230.

- ↑ Robert Ryal Miller, "Matias Romero: Mexican Minister to the United States during the Juarez-Maximilian Era," Hispanic American Historical Review (1965) 45#2 pp. 228–245 in JSTOR

- ↑ Todd W. Wahlstrom, The Southern Exodus to Mexico: Migration Across the Borderlands After the American Civil War (U of Nebraska Press, 2015).

- ↑ Rachel St. John, "The Unpredictable America of William Gwin: Expansion, Secession, and the Unstable Borders of Nineteenth-Century North America." The Journal of the Civil War Era 6.1 (2016): 56-84. online

- ↑ George D. Harmon, "Confederate Migration to Mexico." The Hispanic American Historical Review 17#4 (1937): 458-487. in JSTOR

- ↑ Jürgen Buchenau, "Foreign Policy, 1821–76," in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1, p. 500, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- ↑ Buchenau, "Foreign Policy, 1821–76," p. 500

- ↑ Paul Garner, Porfirio Díaz, London: Longman/Pearson Education 2001, p. 137.

- ↑ Garner, Porfirio Díaz, p. 139.

- ↑ Garner, Porfirio Díaz, p. 146.

- ↑ "Border Patrol History | U.S. Customs and Border Protection". www.cbp.gov. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ↑ C. Hackett, "The Recognition of the Díaz Government by the United States," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, XXVIII, 1925, 34–55.

- ↑ M. Tinker Salas, In the Shadow of the Eagles: Sonora and the Transformation of the Border During the Porfiriato. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1997.

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 1.

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 2.

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 14.

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 15.

- ↑ Hampton 1910

- ↑ van Wyk 2003, pp. 440–446.

- ↑ "Mr. Taft's Peril; Reported Plot to Kill Two Presidents". Daily Mail. London. October 16, 1909. ISSN 0307-7578.

- ↑ Hammond 1935, pp. 565-66.

- ↑ Harris 2009, p. 213.

- ↑ Peter V. N. Henderson, "Woodrow Wilson, Victoriano Huerta, and the Recognition Issue in Mexico," The Americas (1984) 41#2 pp. 151-176 in JSTOR

- ↑ Friedrich Katz, The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution (1981).

- ↑ "Politics of Mexican Oil" (PDF).

- ↑ Jürgen Buchanau, "Foreign Policy, 1946–1996," in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1, p. 511. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- ↑ Buchanau, "Foreign Policy, 1946–1996," pp. 510–11. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- ↑ Buchenau, "Foreign Policy, 1946–1996," pp. 511–12.

- ↑ Buchenau, "Foreign Policy, 1946–1996," p. 512.

- ↑ Jun 2010 - Top Ten U.S. Trading Partners

- ↑ Jun 2009 - U.S. - Mexico At a Glance

- ↑ Michael Hoefer, Nancy Rytina and Bryan C. Baker. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2009. Office of Homeland Security, January 2009.

- ↑ "Border-Crossing Deaths Have Doubled Since 1995; Border Patrol's Efforts to Prevent Deaths Have Not Been Fully Evaluated" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. August 2006. p. 42.

- ↑ "Migration Can Deliver Welfare Gains, Reduce Poverty, Says Global Economic Prospects 2006". Web.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ↑ Michael P. Dino, Evaluator-in-Charge & James R. Russell, Evaluator. December 1994 Border Control: Revised Strategy Is Showing Some Positive; Results: Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Information, Justice, Transportation and Agriculture, Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/govpubs/gao/gao13.htm

- ↑ Foreign Affairs, July/August 2010, page 45

- ↑ Zoe Conway (24 August 2012). "Mexico police fire on US embassy staff". BBC News. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ↑ Jo Tuckman (24 August 2012). "US embassy staff shot at by Mexican police". The Guardian. Mexico City. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ↑ "Mexico Shooting: Agents Who Shot U.S. Embassy Vehicle Were Reportedly Probing A Kidnapping". Huffington Post. Associated Press. 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ↑ Michael Weissensteinolga R. Rodriguez (4 September 2012). "Mexico: Attack on US embassy car was an accident". Bloomberg Business Week. Associated Press. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ↑ E. Eduardo Castillo; Mark Stevenson; Elliot Spagat (2 October 2012). "AP EXCLUSIVE: US CAR WAS TARGETED IN MEXICO AMBUSH". Associated Press. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

Further reading

- Adams, John A. Bordering the Future: The Impact of Mexico on the United States (2006), 184pp

- Arbelaez, Harvey; Milman, Claudio (2007), "The New Business Environment of Latin America and the Caribbean", International Journal of Public Administration, p. 553.

- Berger, Dina. The development of Mexico's tourism industry: Pyramids by day, martinis by night (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006)

- Britton, John A. (1995). Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. University Press of Kentucky.

- Bustamante, Ana Marleny. "The Impact of Post-9/11 US Policy on the California–Baja California Border Region." Journal of Borderlands Studies (2013) 28#3 pp: 307–319.

- Castañeda, Jorge G. "NAFTA's Mixed Record: The View from Mexico." Foreign Affairs 93 (2014): 134. online

- Castro-Rea, Julián, ed. Our North America: Social and Political Issues Beyond NAFTA (Ashgate, 2013)

- Cline, Howard F. The United States and Mexico (Harvard University Press, rev. ed. 1961)

- Díaz, George T. Border Contraband: A History of Smuggling across the Rio Grande (University of Texas Press, 2015) xiv, 241 pp. excerpt

- Domínguez, Jorge I.; Rafael Fernández de Castro (2009). The United States and Mexico: Between Partnership and Conflict. Taylor & Francis.

- Dunn, Christopher; Brewer, Benjamin; Yukio, Kawano (2000), "Trade Globalization since 1795: Waves of Integration in the World-System", American Sociological Review, 65, pp. 77–95, doi:10.2307/2657290.

- Fox, Claire F. The Fence and the River: Culture and Politics at the US–Mexico Border (U of Minnesota Press, 1999)

- Gereffi, Gary; Hempel, Lynn (1996), "Latin America in the Global Economy: Running Faster to Stay in Place", Report on the Americas, retrieved 2008-04-29.

- Haley, P. Edward. Revolution and Intervention: The Diplomacy of Taft and Wilson with Mexico, 1910–1917 (MIT Press, 1970)

- Harris, Charles H. III; Sadler, Louis R. (2009). The Secret War in El Paso: Mexican Revolutionary Intrigue, 1906-1920. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4652-0.

- Hill, John; D'souza, Giles (1998), "Tapping the Emerging Americas Market", Journal of Business Strategy.

- Henderson, Timothy J. A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and Its War with the United States (2007). focus on causation from Mexican perspective

- Hinojosa, Victor J. Domestic Politics and International Narcotics Control: U.S. Relations with Mexico and Colombia, 1989–2000 (2007)

- Kelly, Patricia; Massey, Douglas (2007), "Borders for Whom? The Role of NAFTA in Mexico-U.S. Migration", The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political Science, 610, pp. 98–118, doi:10.1177/0002716206297449.

- Meyer, Lorenzo. Mexico and the United States in the oil controversy, 1917–1942 (University of Texas Press, 2014)

- Moreno, Julio. Yankee don't go home!: Mexican nationalism, American business culture, and the shaping of modern Mexico, 1920–1950 (University of North Carolina Press, 2003)

- Mumme, Stephen (2007), "Trade Integration, Neoliberal Reform and Environmental Protection in Mexico: Lessons for the Americas", Latin American Perspectives, 34, pp. 91–107, doi:10.1177/0094582x07300590.

- Pastor, Robert A. Limits to Friendship: The United States and Mexico (Vintage, 2011)

- Pletcher, David M. The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War (University of Missouri Press, 1973)

- Rives, George Lockhart (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848 (Volume 1). C. Scribner's Sons.

- Santa Cruz, Arturo. Mexico–United States Relations: The Semantics of Sovereignty (Routledge, 2012)

- Simon, Suzanne. Sustaining the Borderlands in the Age of NAFTA: Development, Politics, and Participation on the US-Mexico Border. Vanderbilt University Press, 2014.

- Plana, Manuel. "The Mexican Revolution and the U.S. Border: Research Perspectives," Journal of the Southwest Winter 2007, Vol. 49 Issue 4, pp 603–613, historiography

- Weintraub, Sidney. Unequal Partners: The United States and Mexico (University of Pittsburgh Press; 2010) 172 pages; Focuses on trade, investment and finance, narcotics, energy, migration, and the border.

- White, Christopher. Creating a Third World: Mexico, Cuba, and the United States during the Castro Era (2007)

In Spanish

- Bosch García, Carlos. Documentos de la relación de México con los Estados Unidos. (Spanish) Volumes 1–2. National Autonomous University of Mexico, 1983. ISBN 968-5805-52-0, ISBN 978-968-5805-52-0.

- Terrazas y Basante, Marcela, and Gerardo Gurza Lavalle. Las relaciones México–Estados Unidos, 1756–2010: Tomo I: Imperios, repúblicas, y pueblos en pugna por el territorio, 1756–1867 (The Mexican-American Relationship, 1756–2010: Part 1; Empires, Republics, and People Fighting for the Territory, 1756–1867). Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2012.

- Terrazas y Basante, Marcela, and Gerardo Gurza Lavalle. Las relaciones México–Estados Unidos, 1756–2010: Tomo II: ¿Destino no manifesto?, 1867–2010. (The Mexican–American Relationship, 1756–2010: Part 2: A Non-Manifest Destiny?, 1867-2010). Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2012.

External links

- History of Mexico - U.S. relations

- Economic and Political Relationship from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- A Continent Divided: The U.S. - Mexico War, Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, the University of Texas at Arlington

.svg.png)