French Indochina in World War II

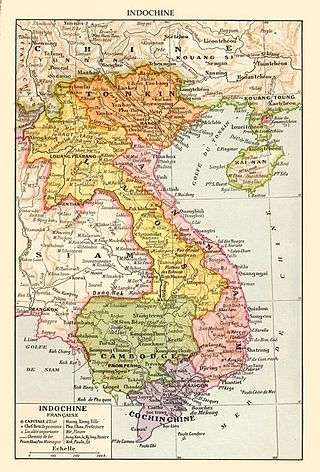

In 1940, France was swiftly defeated by Nazi Germany, and colonial administration of French Indochina, modern-day Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, passed to the Vichy French government, a Puppet state of Nazi Germany. The Vichy government ceded control of Hanoi and Saigon in 1940 to Japan, and in 1941, Japan extended its control over the whole of French Indochina. The United States, concerned by this expansion, put embargoes on exports of steel and oil to Japan. The desire to escape these embargoes and become resource self-sufficient ultimately led to Japan's decision on December 8, 1941 to attack the British Empire in Hong Kong, Malaya and Singapore and simultaneously the USA at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. This led to the USA declaring war against Japan. The US then joined the British Empire, already at war with Germany since 1939, and its existing allies in the fight against the Axis nations. .

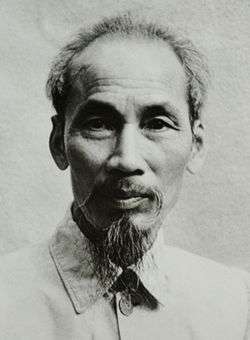

Indochinese Communists had set up hidden headquarters in 1941, but most of the Vietnamese resistance to Japan, France or both, including both communist and non-communist groups, remained based over the border, in China. As part of the Allied fighting against the Japanese, the Chinese formed a nationalist resistance movement, the Dong Minh Hoi (DMH); this included Communists, but was not controlled by them. When this did not provide the desired intelligence data, they released Ho Chi Minh from jail, and he returned to lead an underground centered on the Communist Viet Minh. This mission was assisted by Western intelligence agencies, including the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS).[1] Free French intelligence also tried to affect developments in the Vichy-Japanese collaboration.

In March 1945, the Japanese imprisoned the Vichy French and took direct control of Vietnam until they were defeated by the Allies in August. At that point, there was an attempt to form a Provisional Government, but the French took back control of the country in 1946.

In looking at the broad picture of Southeast Asia at the end of World War II, several conflicting movements appear:

- generic Western anticommunism that saw the French as protector of the area from Communist expansion

- nationalist and anti-colonialist movements that wanted independence from the French

- Communists who indeed would like to expand.

The lines were not always clear, and some alliances were of convenience. Prior to his death, Franklin D. Roosevelt made numerous comments about not wanting the French to regain control of Indochina.[2]

In 1999, former U.S. Secretary of Defense and architect of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam Robert McNamara wrote that both sides had missed opportunities. The U.S. had both ignored its own Office of Strategic Services (OSS) intelligence reports on Ho's nationalism, and failed, when the Truman Administration became suspicious he was merely a Soviet pawn, to probe the situation. He found U.S. claims unconvincing that China was a threat, given a millennium of Sino-Vietnamese enmity, as well as Dean Acheson's claim that the French "blackmailed" the U.S. into supporting them. On Ho's part, McNamara believes they misinterpreted the lack of U.S. response to be equivalent to enmity, and, allowed themselves to be blackmailed by the Soviets and Chinese.[3]

Pre-war events

1936

In France itself, an anti-fascist Popular Front, included the Center, Left, and Communists, stated a new policy for all French colonies, not just Indochina. A corresponding Indochinese Democratic Front formed.

An unpopular Governor General was replaced, encouraging Vietnamese nationalists to meet a French commission of Inquiry with lists of grievances. By the time the commission arrived, however, the Leftists were now not just members of an opposition, but part of a government concerned about Japanese expansion. Socialist Minister for the Colonies Marius Moutet, in September, sent a message to French officials in Saigon, "You will maintain public order...the improvement of the political and economic situation is our preoccupation but...French order must reign in Indochina as elsewhere." Moutet's Popular Front failed in actually liberalizing the situation, and he was to be involved in a greater failure a decade later.[4]

1937

Throughout East and Southeast Asia, tensions had been building between 1937 and 1941, as Japan expanded into China. Franklin D. Roosevelt regarded this as an infringement on U.S. interests in China.[5] The U.S. had already accepted an apology and indemnity for the Japanese bombing of the USS Panay, a gunboat on the Yangtze River in China.

1938

The French Popular Front fell, and the Indochinese Democratic Front went underground.[6] When a new French government, still under the Third Republic, formed in August 1938, among its principal concerns were security of metropolitan France as well as its empire.

Among its first acts was to name General Georges Catroux governor general of Indochina. He was the first military governor general since French civilian rule had begun in 1879, following the conquest starting in 1858.,[7] reflecting the single greatest concern of the new government: defense of the homeland and the defense of the empire. Catroux's immediate concern was with Japan, who were actively fighting in nearby China.

1939

Both the French and Indochinese Communist parties were outlawed.[6]

World War II

1940

After the defeat of France, with an armistice on June 22, 1940, roughly two-thirds of the country was put under direct German military control. The remaining part of southeast France, and the French colonies, were under a nominally independent government, headed by the First World War hero, Marshal Philippe Pétain, with its capital at Vichy. Japan, not yet allied with Germany until the signing of the Tripartite Pact in September 1940, asked for German help in stopping supplies going through Indochina to China.

Increased Axis pressure

Catroux, who had first asked for British support, had no source of military assistance from outside France, stopped the trade to China to avoid further provoking the Japanese. A Japanese verification group, headed by Issaku Nishimura entered Indochina on June 25.

On the same day that Nishimura arrived, Vichy dismissed Catroux, for independent foreign contact. He was replaced by Vice Admiral Jean Decoux, who commanded the French naval forces in the Far East, and was based in Saigon. Decoux and Catroux were in general agreement about policy, and considered managing Nishimura the first priority.[8] Decoux had additional worries. The senior British admiral in the area, on the way from Hong Kong to Singapore, visited Decoux and told him that he might be ordered to sink Decoux's flagship, with the implicit suggestion that Decoux could save his ships by taking them to Singapore, which appalled Decoux. While the British had not yet attacked French ships that would not go to the side of the Allies, that would happen at Mers-el-Kébir in North Africa within two weeks;[9] it is not known if that was suggested to, or suspected by, Decoux. Deliberately delaying, Decoux did not arrive in Hanoi until July 20, while Catroux stalled Nishimura on basing negotiations, also asking for U.S. help.[10]

Reacting to the initial Japanese presence in Indochina, on July 5, the U.S. Congress passed the Export Control Act, banning the shipment of aircraft parts and key minerals and chemicals to Japan, which was followed three weeks later by restrictions on the shipment of petroleum products and scrap metal as well.[11]

Decoux, on August 30, managed to get an agreement between the French Ambassador in Tokyo and the Japanese Foreign Minister, promising to respect Indochinese integrity in return for cooperation against China. Nishimura, on September 20, gave Decoux an ultimatum: agree to the basing, or the 5th Division, known to be at the border, would enter.

Japan entered Indochina on September 22, 1940. An agreement was signed, and promptly violated, in which Japan promised to station no more than 6,000 troops in Indochina, and never have more than 25,000 transiting the colony. Rights were given for three airfields, with all other Japanese forces forbidden to enter Indochina without Vichy consent. Immediately after the signing, a group of Japanese officers, in a form of insubordination not uncommon in the Japanese military, attacked the border post of Đồng Đăng, laid siege to Lam Son, which, four days later, surrendered. There had been 40 killed, but 1,096 troops had deserted.[12]

With the signing of the Tripartite Pact on September 27, 1940, creating the Axis of Germany, Japan, and Italy, Decoux had new grounds for worry: the Germans could pressure the homeland to support their ally, Japan.

Japan apologized for the Lam Song incident on October 5. Decoux relieved the senior commanders he believed should have anticipated the attack, but also gave orders to hunt down the Lam Song deserters, as well as Viet Minh who had entered Indochina while the French seemed preoccupied with Japan.

Through much of the war, the French colonial government had largely stayed in place, as the Vichy government was on reasonably friendly terms with Japan. Japan had not entered Indochina until 1941, so the conflicts from 1939 to the fall of France had little impact on a colony such as Indochina. The Japanese permitted the French to put down nationalist rebellions in 1940.[13]

1941

A contributing factor to the 1941 escalations by Japan, however, resulted when Japan expanded its position in Indochina.

The birth of the Viet Minh

In February, 1941, Ho Chi Minh returned to Vietnam and established his base in a cave at Pac Bo in Cao Bằng Province, near the Sino-Vietnamese border. In May, the Indochinese Communist Party convened its eighth plenum where it placed nationalist goals ahead of communist goals: it prioritized the independence of Vietnam ahead of leading the communist revolution, fomenting class war, or aiding the workers. To that end, the plenum established the "League for the Independence of Vietnam" (Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi, Viet Minh for short). All Vietnamese political groups were welcomed to join the Viet Minh provided they supported ICP-led action against the Japanese and French colonizers. Ho Chi Minh's greatest accomplishment during this period was unifying urban nationalist groups with his own peasant communist rebels and creating a single anti-colonial independence movement.[14]

Vichy agreements with Japan about Indochina

Vichy signed the Protocol Concerning Joint Defense and Joint Military Cooperation on July 29. This agreement defined the Franco-Japanese relationship for Indochina, until the Japanese abrogated it in March 1945. It gave the Japanese a total of eight airfields, allowed them to have more troops present, and to use the Indochinese financial system, in return for a fragile French autonomy.

In late November, the United States told the Japanese that it must give up all occupied territories in Indochina and China, and withdraw from the Axis. Especially with U.S. Magic communications intelligence on the Japanese diplomatic correspondents, war seemed imminent. A "warning of a state of war" went to U.S. forces in the Pacific.

24,000 Japanese troops sailed, in December, from Vietnam to Malaya.[15]

1942

The Chinese organized the Dong Min Hoi (DMH) coalition to gain intelligence from Indochina, a coalition dominated by the VNQDĐ. The only actual assets in Indochina, however, were Viet Minh.

During the Japanese occupation, even during French administration, the Viet Minh exiled to China had an opportunity to quietly rebuild their infrastructure. They had been strongest in Tonkin, the northern region, so moving south from China was straightforward. They had a concept of establishing "base areas" (chien khu) or "safe areas" (an toan khu), often mountainous jungle.[16] Of these areas, the "homeland" of the VM was near Bắc Kạn Province.[14] (see map[17])

Additional chien khu developed in Yên Bái Province, Thái Nguyên Province (the "traditional" stronghold of the PCI), Quảng Ngãi Province (Ho's birthplace), Pac Bo in Cao Bằng Province, Ninh Bình Province and Dong Trieu in Quảng Ninh Province. As did many revolutionary movements, part of building their base was providing "shadow government" services. They attacked landlords and moneylenders, as well as providing various useful services. They offered education, which contained substantial amounts of political indoctrination.

They collected taxes, often in the form of food supplies, intelligence on enemy movement, and service as laborers rather than in money. They formed local militias, which provided trained individuals, but they were certainly willing to use violence against reluctant villagers. Gradually, they moved this system south, although not obtaining as much local support in Annam, and especially Cochinchina. While later organizations would operate from Cambodia into the regions of South Vietnam that corresponded to Cochin China, this was well in the future.

Some of their most important sympathizers included educated civil servants and soldiers, who provided clandestine human-source intelligence from their workplaces, as well as providing counterintelligence on French and Japanese plans.

In August, Ho, while meeting with Chinese Communist Party officials, was held, for two years, by the Kuomintang.[14]

1943

To make the Dong Minh Hoi an effective intelligence operation, the Chinese released Ho and put him in charge, replacing the previously Kuomintang-affiliated Vietnamese nationalists.

1944

In 1944, Ho, then in China, had requested a United States visa to go to San Francisco to make Vietnamese language broadcasts of material from the U.S. Office of War Information, the U.S. official or "white" propaganda. The visa was denied.[18]

By August, Ho convinced the Kuomintang commander to support his return to Vietnam, leading 18 guerrillas against the Japanese. Accordingly, Ho returned to Vietnam in September with eighteen men trained and armed by the Chinese. Discovering that the ICP had planned a general uprising in the Việt Bắc, he disapproved, but encouraged the establishment of "armed propaganda" teams.[14]

The end of Western rule

The Japanese revoked French administrative control on March 9th and took French administrators prisoner. They murdered those who refused to initially surrender and/or comply with their demands. This had the secondary effect of cutting off much Western intelligence about the Japanese in Indochina.[19] They retained Bảo Đại as a nominal leader.

Even before there was a Vietnamese government, the French Provisional Government declared an intention, on March 24, to have a French Union that would include an Indochinese Federation. While France would retain control over foreign relations and major military programs, the Federation would have its own military, and could form relationships outside the Federation, especially with China.[20]

There would, however, continue to be a top French official, called High Commissioner rather than Governor General, but still in control. The five states, Annam, Cambodia, Cochin China, Laos, and Tonkin would continue; there would be no Vietnam. In August, Admiral Georges d'Argenlieu would be named as High Commissioner,[21] with Gen. Jacque Leclerc as his military deputy.

Ho's forces rescued an American pilot in March. Washington ordered Patti to do whatever was necessary to reestablish the intelligence flow, and the OSS mission was authorized to contact Ho. He asked to meet Gen. Claire Chennault, the American air commander, and that was agreed, under the condition he did not ask for supplies or active support.

The visit was polite but without substance. Ho, however, asked for the minor favor of an autographed picture of Chennault. Later, Ho used that innocent item to indicate, to other Northern groups, that he had American support.[22]

Following the Japanese assumption of power in March 1945, they created a government under Bảo Đại. He invited Ngô Đình Diệm to become Prime Minister but, after receiving no response, turned to Trang Trong Kim and formed a cabinet of French-trained but nationalist ministers.[23]

His authority extended only to Tonkin and Annam; the Japanese simply replaced the former French officials in Cochinchina; Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo members also gained power there.

Cambodia in World War II

Following Japan's entry into Indochina on 22 September 1940, the Thai government, under the pro-Japanese leadership of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram, and strengthened by virtue of its treaty of friendship with Japan, invaded French Protectorate of Cambodia's western provinces to which it had historic claims. Following the Franco-Thai War, Tokyo hosted the signature of a treaty on 9 May 1941 that formally compelled the French to relinquish one-third of the surface area of Cambodia with almost half a million citizens.[24]

In August 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army entered the French protectorate of Cambodia and established a garrison that numbered 8,000 troops. Despite their military presence, the Japanese authorities allowed Vichy French colonial officials to remain at their administrative posts but in 1945, in the closing stages of World War II, Japan made a coup de force that temporarily eliminated French control over Indochina. The French colonial administrators were relieved of their positions, and French military forces were ordered to disarm. The aim was to revive the support of local populations for Tokyo's war effort by encouraging indigenous rulers to proclaim independence.

On 9 March 1945, young king Norodom Sihanouk proclaimed an independent Kingdom of Kampuchea, following a formal request by the Japanese. The Japanese occupation of Cambodia ended with the official surrender of Japan in August 1945 and the Cambodian puppet state lasted until October 1945.

Some supporters of the kingdom's prime minister Son Ngoc Thanh escaped to north-western Cambodia, then still under Thai control, where they banded together as one faction in the Khmer Issarak movement. Though their fortunes rose and fell during the immediate postwar period, by 1954 the Khmer Issarak operating with the Viet Minh by some estimates controlled as much as 50 percent of Cambodia's territory.

King Sihanouk reluctantly proclaimed a new constitution on 6 May 1947. While it recognized him as the "spiritual head of the state", it reduced him to the status of a constitutional monarch of a Cambodia within the French Union.

Laos during World War II

Thai Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram had plans to unify all Tai peoples, including the Lao, under one nation. Following the Franco-Thai War, Japan compelled the Vichy French colonial government to cede parts of the French Protectorate of Laos to Thailand.[25]

In order to maintain support and expel both the Japanese and Thai, colonial governor Jean Decoux encouraged the rise of the Lao nationalist Movement for National Renovation but, in the south of the country, the Lao Sēri movement was formed in 1944 and was not supportive of the French.

In March 1945, Japan dissolved French control over its Indochinese colonies and large numbers of French officials in Laos were then imprisoned. King Sisavang Vong was forced into declaring Laotian independence on 8 April and accepting the nation in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. At the same time, remaining French officials and civilians withdrew to the mountains to regroup and join a growing Laotian insurgency led by Crown Prince Savang Vatthana against the Japanese, which occupied Vientiane in March 1945. Japan continued to rule Laos directly despite constant civil unrest until it was forced to withdraw in August 1945.

Following the Japanese surrender, Prince Phetsarath Rattanavongsa made an attempt to convince King Savang to officially unify the country and declare the treaty of protection with the French invalid because the French had been unable to protect the Lao from the Japanese. However, King Savang said that he intended to have Laos resume its former status as a French colony.

In October 1945, supporters of Laotian independence announced the dismissal of the king and formed the new government of Laos, the Lao Issara, to fill up the power vacuum of the country.[26] However, the Lao Issara was bankrupt and ill equipped, and could only await the inevitable French return. At the end of April 1946 the French took Vientiane, by May they had entered Luang Prabang, and the Lao Issara leadership fled into exile in Thailand. On 27 August 1946, the French formally endorsed the unity of Laos as a constitutional monarchy within the French Union.

U.S. postwar policy

Franklin D. Roosevelt had expressed a strong preference for national self-determination, and was not notably pro-French.[27] Cordell Hull's memoirs say that Roosevelt

entertained strong views on independence for French Indo-China. That French dependency stuck in his mind as having been the springboard for the Japanese attack on the Philippines, Malaya, and the Dutch East Indies. He could not but remember the devious conduct of the Vichy Government in granting Japan the right to station troops there, without any consultation with us but with an effort to make the world believe we approved.[28]

After his death, however, the Truman administration, having experienced very real confrontations such as the Berlin Blockade in 1948-1949, where the French were allies in dealing with the Blockade. French forces also had a key the defense of Western Europe from the Soviet expansion that had already taken much of Eastern Europe. Harry S. Truman saw the French as necessary allies. The rise of the Chinese Communists in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 strengthened the hand of those who saw resistance to Communism in East and Southeast Asia as dominating all other issues there. Ousted Chinese Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek, exiled to Taiwan, had strong U.S. political allies such as Claire Chennault. Increasingly, and especially with the rise of Joe McCarthy, there was also, at the public level, a reflexive condemnation of anything with the slightest Communist connection, or even generally leftist.[29]

During this period, France was perceived as more and more strategic to Western interests, and, both to strengthen it vis-a-vis the Soviet Union and Western Union, and against the perceived threat of Ho and the Chinese Communists, the U.S. would support French policy. Vietnamese nationalism or the discouragement of colonialism was really not a matter of consideration.

Laos, also a proto-state in the French Union, became of concern to the U.S. After the Japanese were removed from control of the Laotian parts of Indochina, three Lao princes created a movement to resist the return of French colonial rule. Within a few years, Souvanna Phouma returned and became prime minister of the colony. Souphanouvong, seeing the Viet Minh as his only potential ally against the French, announced, while in the Hanoi area, the formation of the "Land of Laos" organization, or Pathet Lao. Unquestionably, the Pathet Lao were Communist-affiliated. Nevertheless, they soon became a focus of U.S. concern, which, in the Truman and Eisenhower administrations, was more focused on anticommunism than any nationalist or anticolonial movement.[29]

In contrast with other Asian colonies like India, Burma, the Philippines and Korea, Vietnam was not given its independence after the war. As in Indonesia (the Dutch East Indies), an indigenous rebellion demanded independence. While the Netherlands was too weak to resist the Indonesians, the French were strong enough to just barely hold on. As a result, Ho and his Viet Minh launched a guerrilla campaign, using Communist China as a sanctuary when French pursuit became hot.

Viet Minh insurgency

Just after the Japanese surrender, before the Japanese-imprisoned French returned to their desks, Vietnamese guerrillas, under Ho Chi Minh, had seized power in Hanoi and shortly thereafter demanded and received the abdication of the apparent French puppet, Emperor Bảo Đại. This would not be the last of Bảo Đại.

In August 1945, two three-man French teams, under COL Henri Cedile, the Commissioner for Cochin China, and MAJ Pierre Messmer, Commissioner for northern Indochina, parachuted, from U.S. aircraft, into Indochina.

Reporting to High Commissioner d'Argenlieu, they were the first new French representatives. Cedile was almost immediately given to the Japanese. He was driven to Saigon, seminude, as a prisoner. Messmer was held by Vietnamese, and his team was given poison; one died before they escaped to China.[30] Jean Sainteny later became the Commissioner for the north.

These were the first of the officers who would replace the French officials that had worked under Vichy rule. High officers, such as Admiral Decoux, would be sent back to France and sometimes tried for collaboration, but Cedile and Sainteny generally kept the French lower-level staff.

Earlier in 1945, Pham Ngoc Thach, deputy minister in Ho's personal Office of the President, had met,in Saigon, with U.S. OSS LTC A. Peter Dewey, along with Pham Van Bach, to try to negotiate with the French. Both the Vietnamese and French sides were factionalized. Adding to the confusion was the British Gurkha force under MG Douglas Gracey, who refused to let Dewey fly a U.S. flag on his car. Dewey was killed at a Viet Minh roadblock in September.[31]

Brief revolution

Ho Chi Minh declared independence in September. In a dramatic speech, he began with

All men are created equal. The Creator has given us certain inalienable rights: the right to Life, the right to be Free, and the right to achieve Happiness...These immortal words are taken from the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America in 1776. In a larger sense, this means that: all the peoples of the world are equal; all the people have the right to live, to be happy, to be free. turning to the Declaration of the French Revolution in 1791, "It also states Men are born, must be free, and have equal rights. These are undeniable truths.[32]

Ho's declaration had none but emotional impact; the French soon reestablished their authority after the Japanese surrendered. We have no way to know how much of this Ho believed, but it should be remembered as an example of how he understood the thinking of those who would become his enemy, while Lyndon Baines Johnson and Robert S. McNamara never seemed to grasp his beliefs in the willingness to accept protracted war and great losses, in the interest of eventual control.

Cochin China, at this time, was far less organized than Tonkin. Cao Đài set up a state around Tây Ninh, while Hòa Hảo declared one in the Cần Thơ area. These sects, along with a non-Viet Minh Trotskyite faction, formed the United National Front (UNF), which demonstrated on August 21. The Viet Minh, however, called for the UNF to accept its authority, else let the French to declare all Vietnamese nationalism a Japanese proxy, and the UNF tentatively accepted this on the 25th.

The non-Communist nationalists became increasingly suspicious believing the Viet Minh Committee of the South was cooperating with COL Cedile. Mass demonstrations took place in Saigon on the 2nd, and shots were fired at it; the perpetrators were not identified.

Through the OSS Patti mission, often through emissaries,[33] from the fall of 1945 to the fall of 1946, the United States received a series of communications from Ho Chi Minh depicting calamitous conditions in Vietnam, invoking the principles proclaimed in the Atlantic Charter and in the Charter of the United Nations, and pleading for U.S. recognition of the independence of the DRV, or — as a last resort — trusteeship for Vietnam under the United Nations.

British and French troops landed in Saigon on September 12, with their commander, MG Douglas Gracey, arriving the next day. Gracey's headquarters instructed him, on the 13th, to exercise control only in limited areas, at French request, and after approval by the Southeast Asia [theater] Command under Field Marshal Sir William Slim. He was responsible for taking the Japanese surrender, and acting in temporary command of both British and French troops.

Cedile, on 18 September, asked Dewey, in Saigon, to try to head off the threatened Viet Minh general strike. Dewey met with Thach and other Vietnamese, and took back the message "it would be extremely difficult, at [this] point in time to control the divergent political factions — not all pro-Viet Minh, but all anti-French." [34]

On 21–22 September 1945, British Gurkhas, under Gracey, took the central prison back from the Japanese, releasing French paratroopers. Cedile, with those paratroopers, captured several Japanese-held police stations on the 22nd, and then took control of the administrative areas on the 23rd. Some Viet Minh guards were shot. French control was reasserted.[35]

Patti's guidance was that the U.S. had essentially given up the idea of a trusteeship, but still, at the U.N. foundation conferences, the U.S. was in favor of gradual independence.[36] But while the U.S. took no action on Ho's requests, it was also unwilling to aid the French.[37]

It has been suggested that the Viet Minh accepted a significant number of Japanese troops, estimated by Goscha as at least 5,000, who had no immediate way to get back to Japan, and often had ties to the local culture. Their experience in a conventional military would have been welcome.[38]

See also

References

- ↑ Patti, Archimedes L. A. (1980). Why Viet Nam? Prelude to America's Albatross. University of California Press. ISBN 0520041569., p. 477

- ↑ Patti, p. 17

- ↑ McNamara, Robert S.; Blight, James G.; Brigham, Robert Kendall (1999), Argument Without End: In Search of Answers to the Vietnam Tragedy, PublicAffairs, ISBN 1586486217, pp.95-99

- ↑ Hammer, Ellen J. (1955), The Struggle for Indochina 1940-1955: Vietnam and the French Experience, Stanford University Press, pp. 91-92

- ↑ Arima, Yuichi (December 2003), "The Way to Pearl Harbor: US vs Japan", ICE Case Studies, the American University (118)

- 1 2 Hammer, p. 92

- ↑ Vets with a Mission, World War II - Occupation and Liberation

- ↑ Dommen, Arthur J. (2001), The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans, Indiana University Press, ISBN 0253109256 pp. 47

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (1989), The Second World War, Stoddart, p. 107

- ↑ Dommen, p. 48

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 108

- ↑ Dommen, p. 50-51

- ↑ Hammer, p. 94

- 1 2 3 4 Cima, Ronald J., ed. (1987), "Establishment of the Viet Minh", Vietnam: A Country Study, Library of Congress

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 273

- ↑ Leulliot, Nowfel; O'Hara, Danny, The Tiger and the Elephant: Viet Minh Strategy and Tactics

- ↑ U.S. Department of State (1981), "Viet Bac, Viet Minh base area, 1941-1945", Vietnam: A Country Study

- ↑ Patti, Archimedes L.A. (1980), Why Viet Nam? Prelude to America's Albatross, University of California Press, p. 46

- ↑ Patti, p. 41

- ↑ Hammer, pp. 111-112

- ↑ Patti, pp. 475-477

- ↑ Patti, pp. 57-58

- ↑ Hammer, p. 481

- ↑ Cambodia, The Japanese Occupation, 1941-45

- ↑ Levy, p.89-90

- ↑ Laos and Laotians by Meg Regina Rakow

- ↑ Patti 1980, p. 17

- ↑ The Memoirs of Cordell Hull, p. 1595

- 1 2 Castle, Timothy N. (May 1991), At War in the Shadow of Vietnam: United States Military Aid to the Royal Lao Government 1955-75 (doctoral thesis), Air Force Institute of Technology, Castle 1991, ADA243492

- ↑ Hammer, pp. 8-9

- ↑ Patti, pp. 310-311

- ↑ Patti, pp. 250-253

- ↑ Patti, p. 68

- ↑ Patti, p. 318

- ↑ Patti, pp. 315-316

- ↑ Patti, pp. 266-267

- ↑ "Chapter I, "Background to the Crisis, 1940-50" Section 2, pp. 12-29", The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Volume 1

- ↑ Ford, Dan, Japanese soldiers with the Viet Minh

Bibliography

- Verney, Sébastien. L'Indochine sous Vichy: entre Révolution nationale, collaboration et identités nationales, 1940-1945. Paris: Riveneuve. ISBN 2360130749.

- Jennings, Eric T. (2001). Vichy in the Tropics: Petain's National Revolution in Madagascar, Guadeloupe, and Indochina, 1940-44. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804750475.

- Jennings, Eric T. (Summer 2004). "Conservative Confluences, "Nativist" Synergy: Reinscribing Vichy's National Revolution in Indochina, 1940-1945". French Historical Studies. Writing French Colonial Histories. 27 (3): 601–35. doi:10.1215/00161071-27-3-601. JSTOR 40324405.

- Namba, Chizuru (2012). Français et Japonais en Indochine, 1940-1945: Colonisation, Propagande et Rivalité culturelle. Paris: Karthala. ISBN 9782811106744.