WikiLeaks

|

| |

|

Screenshot

Screenshot of WikiLeaks' main page | |

Type of site | Document archive and disclosure |

|---|---|

| Available in | English, but the documents are written in various others |

| Owner | Sunshine Press |

| Created by | Julian Assange |

| Slogan(s) | "We open governments"[1] |

| Website |

WikiLeaks |

| Alexa rank |

|

| Commercial | No[4] |

| Registration | None |

| Launched | 4 October 2006[5] |

| Current status | Online |

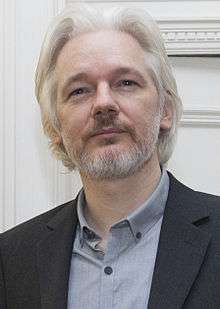

WikiLeaks /ˈwɪkiliːks/ is an international non-profit organisation that publishes secret information, news leaks,[6] and classified media from anonymous sources.[7] Its website, initiated in 2006 in Iceland by the organisation Sunshine Press,[8] claimed a database of more than 1.2 million documents within a year of its launch.[9] Julian Assange, an Australian Internet activist, is generally described as its founder, editor-in-chief, and director.[10] Kristinn Hrafnsson, Joseph Farrell, and Sarah Harrison are the only other publicly known and acknowledged associates of Assange.[11] Harrison is also a member of Sunshine Press Productions along with Assange and Ingi Ragnar Ingason.[12][13]

The group has released a number of significant documents that have become front-page news items. Early releases included documentation of equipment expenditures and holdings in the Afghanistan war and a report informing a corruption investigation in Kenya.[14] In April 2010, WikiLeaks published gunsight footage from the 12 July 2007 Baghdad airstrike in which Iraqi journalists were among those killed by an AH-64 Apache helicopter, known as the Collateral Murder video. In July of the same year, WikiLeaks released Afghan War Diary, a compilation of more than 76,900 documents about the War in Afghanistan not previously available to the public.[15] In October 2010, the group released a set of almost 400,000 documents called the "Iraq War Logs" in coordination with major commercial media organisations. This allowed the mapping of 109,032 deaths in "significant" attacks by insurgents in Iraq that had been reported to Multi-National Force – Iraq, including about 15,000 that had not been previously published.[16][17] In April 2011, WikiLeaks began publishing 779 secret files relating to prisoners detained in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[18]

In November 2010, WikiLeaks collaborated with major global media organisations to release U.S. State Department diplomatic "cables" in redacted format. On 1 September 2011, it became public that an encrypted version of WikiLeaks' huge archive of unredacted U.S. State Department cables had been available via BitTorrent for months and that the decryption key (similar to a password) was available to those who knew where to find it. WikiLeaks blamed the breach on its former publication partner, the UK newspaper The Guardian, and that newspaper's journalist David Leigh, who revealed the key in a book published in February 2011.[19] The Guardian argued that WikiLeaks was to blame since they had given the impression that the encrypted file was temporary, taking it offline seven months before the book was published.[20] The German periodical Der Spiegel reported a more complex story[21] involving errors on both sides. The incident resulted in widely expressed fears that the information released could endanger people, but investigations failed to identify anyone who had been harmed.[22][23]

History

Founding

The wikileaks.org domain name was registered on 4 October 2006.[5] The website was established and published its first document in December 2006.[24][25] WikiLeaks has been predominantly represented in public since January 2007 by Julian Assange, who is now generally recognised as the "founder of WikiLeaks".[26] According to the magazine Wired, a volunteer said that Assange described himself in a private conversation as "the heart and soul of this organisation, its founder, philosopher, spokesperson, original coder, organiser, financier, and all the rest".[27]

WikiLeaks relies to some degree on volunteers and previously described its founders as a mixture of Asian dissidents, journalists, mathematicians, and start-up company technologists from the United States, Taiwan, Europe, Australia, and South Africa,[28] but has progressively adopted a more traditional publication model and no longer accepts either user comments or edits. As of June 2009, the website had more than 1,200 registered volunteers[28] and listed an advisory board comprising Assange, his deputy Jash Vora and seven other people, some of whom denied any association with the organisation.[29][30]

Name

Despite using the name "WikiLeaks", the website has not used the "wiki" publication method since May 2010.[31] Also, despite some popular confusion[32] due to both having "wiki" in their names, WikiLeaks and Wikipedia are not affiliated with each other ("wiki" is not a brand name);[33][34] Wikia, a for-profit corporation affiliated loosely with the Wikimedia Foundation, did purchase several WikiLeaks-related domain names (including wikileaks.com and wikileaks.net) as a "protective brand measure" in 2007.[35]

Purpose

According to the WikiLeaks website, its goal is "to bring important news and information to the public... One of our most important activities is to publish original source material alongside our news stories so readers and historians alike can see evidence of the truth."

Another of the organisation's goals is to ensure that journalists and whistleblowers are not prosecuted for emailing sensitive or classified documents. The online "drop box" is described by the WikiLeaks website as "an innovative, secure and anonymous way for sources to leak information to [WikiLeaks] journalists".[36]

In an interview as part of the American television program The Colbert Report, Assange discussed the limit to the freedom of speech, saying, "[it is] not an ultimate freedom, however free speech is what regulates government and regulates law. That is why in the US Constitution the Bill of Rights says that Congress is to make no such law abridging the freedom of the press. It is to take the rights of the press outside the rights of the law because those rights are superior to the law because in fact they create the law. Every constitution, every bit of legislation is derived from the flow of information. Similarly every government is elected as a result of people understanding things".[37]

The project has been compared to Daniel Ellsberg's revelation of the "Pentagon Papers" (US war-related secrets) in 1971.[38] In the United States, the "leaking" of some documents may be legally protected. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that the Constitution guarantees anonymity, at least in the context of political discourse.[38] Author and journalist Whitley Strieber has spoken about the benefits of the WikiLeaks project, noting that "Leaking a government document can mean jail, but jail sentences for this can be fairly short. However, there are many places where it means long incarceration or even death, such as China and parts of Africa and the Middle East."[39]

Some describe Wikileaks as a media or journalistic organization. For example, in a 2013 resolution, the International Federation of Journalists, a trade union of journalists, called Wikileaks a "new breed of media organisation" that "offers important opportunities for media organisations."[40] Harvard professor Yochai Benkler has praised WikiLeaks as a new form of journalistic enterprise,[41] testifying at the court-martial of Bradley Manning that "WikiLeaks did serve a particular journalistic function" although "It's a hard line to draw."[42] Other do not consider WikiLeaks to be journalistic in nature. Media ethicist Kelly McBride of the Poynter Institute for Media Studies writes that "Wikileaks might grow into a journalist endeavor. But it's not there yet."[43] Bill Keller of the New York Times considers WikiLeaks to be a "complicated source" rather than a journalistic partner.[43] Prominent First Amendment lawyer Floyd Abrams writes that Wikileaks is not a journalistic group, but instead "an organization of political activists; ... a source for journalists; and ... a conduit of leaked information to the press and the public." [44] Noting Assange's statements that he and his colleagues read only a small fraction of information before deciding to publish it, Abrams writes that "No journalistic entity I have ever heard of--none--simply releases to the world an elephantine amount of material it has not read."[44]

Administration

According to a January 2010 interview, the WikiLeaks team then consisted of five people working full-time and about 800 people who worked occasionally, none of whom were compensated.[45] WikiLeaks does not have any official headquarters. In November 2010 the WikiLeaks-endorsed[46] news and activism site WikiLeaks Central was initiated and was administrated by editor Heather Marsh who oversaw 70+ writers and volunteers.[47] She resigned as editor in chief, administrator and domain holder of WikiLeaks Central on 8 March 2012.[48]

Hosting

WikiLeaks describes itself as "an uncensorable system for untraceable mass document leaking".[49] The website is available on multiple servers and different domain names as a result of a number of denial-of-service attacks and its elimination from different Domain Name System (DNS) providers.[50][51]

Until August 2010, WikiLeaks was hosted by PRQ, a Sweden-based company providing "highly secure, no-questions-asked hosting services". PRQ is said to have "almost no information about its clientele and maintains few if any of its own logs".[52] Currently, WikiLeaks is hosted mainly by the Swedish internet service provider Bahnhof in the Pionen facility, a former nuclear bunker in Sweden.[53][54] Other servers are spread around the world with the main server located in Sweden.[55] Julian Assange has said that the servers are located in Sweden (and the other countries) "specifically because those nations offer legal protection to the disclosures made on the site". He talks about the Swedish constitution, which gives the information providers total legal protection.[55] It is forbidden according to Swedish law for any administrative authority to make inquiries about the sources of any type of newspaper.[56] These laws, and the hosting by PRQ, make it difficult for any authorities to eliminate WikiLeaks; they place an onus of proof upon any complainant whose suit would circumscribe WikiLeaks' liberty, e.g. its rights to exercise free speech online. Furthermore, "WikiLeaks maintains its own servers at undisclosed locations, keeps no logs and uses military-grade encryption to protect sources and other confidential information." Such arrangements have been called "bulletproof hosting".[52][57]

In August 2010, the Swedish Pirate Party announced it would be hosting, managing, and maintaining many of WikiLeaks' new servers without charge.[58][59]

After the site became the target of a denial-of-service attack on its old servers, WikiLeaks moved its website to Amazon.com's servers.[60] Later, however, the website was "ousted" from the Amazon servers.[60] In a public statement, Amazon said that WikiLeaks was not following its terms of service. The company further explained, "There were several parts they were violating. For example, our terms of service state that 'you represent and warrant that you own or otherwise control all of the rights to the content... that use of the content you supply does not violate this policy and will not cause injury to any person or entity.' It's clear that WikiLeaks doesn't own or otherwise control all the rights to this classified content."[61] WikiLeaks was then moved to servers at OVH, a private web-hosting service in France.[62] After criticism from the French government, the company sought two court rulings about the legality of hosting WikiLeaks. While the court in Lille immediately refused to force OVH to deactivate the WikiLeaks website, the court in Paris stated it would need more time to examine the complex technical issue.[63][64]

Do not use PGP to contact us. We have found that people use it in a dangerous manner. Further one of the Wikileaks key on several key servers is FAKE.

WikiLeaks, WikiLeaks:PGP Keys

To preserve anonymity, WikiLeaks staff uses software like Tor[65] and PGP,[66] for communication. PGP may no longer be used though because in November 2007[67] the published PGP key expired. WikiLeaks warned against fake PGP keys on keyservers[68] and proposed as an alternative using a SSL-encrypted chat.[69]

WikiLeaks was implemented on MediaWiki software between 2006 and October 2010.[70] WikiLeaks strongly encouraged postings via Tor because of the strong privacy needs of its users.[71]

On 4 November 2010, Julian Assange told Swiss public television organisation – Télévision Suisse Romande (TSR) that he is seriously considering seeking political asylum in neutral Switzerland and establishing a WikiLeaks foundation to move the operation there.[72][73] According to Assange at the time, Switzerland and Iceland were the only countries where WikiLeaks would be safe to operate.[74][75]

Domain name service

WikiLeaks had been using EveryDNS's domain name system (DNS). Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks against WikiLeaks hurt DNS quality of service for other EveryDNS customers; as a result, the company dropped WikiLeaks. Supporters of WikiLeaks waged verbal and DDoS attacks on EveryDNS. Because of a typographical error in blogs mistaking EveryDNS for competitor EasyDNS, that sizable internet backlash hit EasyDNS. Despite that, EasyDNS (upon request of a customer who was setting up new WikiLeaks hosting) began providing WikiLeaks with DNS service on "two 'battle hardened' servers" to protect quality of service for its other customers.[76]

Tor hidden service

WikiLeaks operates a Tor hidden service to access the website.[77][78]

Verification of submissions

WikiLeaks has contended that it has never released a misattributed document and that documents are assessed before release. In response to concerns about the possibility of misleading or fraudulent leaks, WikiLeaks has stated that misleading leaks "are already well-placed in the mainstream media. WikiLeaks is of no additional assistance."[79] The FAQ states that: "The simplest and most effective countermeasure is a worldwide community of informed users and editors who can scrutinise and discuss leaked documents."[80]

According to statements by Assange in 2010, submitted documents are vetted by a group of five reviewers, with expertise in different topics such as language or programming, who also investigate the background of the leaker if his or her identity is known.[81] In that group, Assange has the final decision about the assessment of a document.[81]

Insurance files

On 29 July 2010 WikiLeaks added an "Insurance file" to the Afghan War Diary page. The file is AES encrypted.[82][83] There has been speculation that it was intended to serve as insurance in case the WikiLeaks website or its spokesman Julian Assange are incapacitated, upon which the passphrase could be published.[84][85] After the first few days' release of the US diplomatic cables starting 28 November 2010, the US television broadcasting company CBS predicted that "If anything happens to Assange or the website, a key will go out to unlock the files. There would then be no way to stop the information from spreading like wildfire because so many people already have copies."[86] CBS correspondent Declan McCullagh stated, "What most folks are speculating is that the insurance file contains unreleased information that would be especially embarrassing to the US government if it were released."[86]

On 22 February 2012, there was another insurance file release.[87][88] The insurance files are not to be confused with another encrypted file containing diplomatic cables, the password of which has been compromised. The insurance files' passwords have not been compromised and their contents are still unknown.

On 17 August 2013, WikiLeaks released another three insurance files.[89] Like previous insurance files, the contents of these three insurance files are still unknown.

On 3 June 2016, WikiLeaks released an 94.09 GiB AES-256 encrypted insurance file.[90][91] Its size is sometimes reported as 87.6 GiB but its actual size is 94.09 GiB.[90]

Operational challenges

Assange has acknowledged that the practice of posting largely unfiltered classified information online could one day cause the website to have "blood on our hands".[25][92] He said that the potential to save people from harm outweighs the danger to them.[93] Furthermore, WikiLeaks has highlighted independent investigations which have failed to find any evidence of civilians harmed as a result of WikiLeaks' activities.[94][95] A surveillance-resistant social network, Friends of WikiLeaks (FoWL), was initiated by sympathisers with the organisation in May 2012 to perform advocacy.[96][97][98]

Legal status

Legal background

The legal status of WikiLeaks is complex. Assange considers WikiLeaks a protection intermediary. Rather than leaking directly to the press, and fearing exposure and retribution, whistleblowers can leak to WikiLeaks, which then leaks to the press for them.[99] Its servers are located throughout Europe and are accessible from any uncensored web connection. The group located its headquarters in Sweden because it has one of the world's strongest laws to protect confidential source-journalist relationships.[100][101] WikiLeaks has stated it does not solicit any information.[100] However, Assange used his speech during the Hack In The Box conference in Malaysia to ask the crowd of hackers and security researchers to help find documents on its "Most Wanted Leaks of 2009" list.[102]

Potential criminal prosecution

The U.S. Justice Department began a criminal investigation of WikiLeaks and Julian Assange soon after the leak of diplomatic cables began.[103][104] Attorney General Eric Holder affirmed the investigation was "not saber-rattling", but was "an active, ongoing criminal investigation".[104] The Washington Post reported that the department was considering charges under the Espionage Act of 1917, an action which former prosecutors characterised as "difficult" because of First Amendment protections for the press.[103][105] Several Supreme Court cases (e.g. Bartnicki v. Vopper) have established previously that the American Constitution protects the re-publication of illegally gained information provided the publishers did not themselves violate any laws in acquiring it.[106] Federal prosecutors have also considered prosecuting Assange for trafficking in stolen government property, but since the diplomatic cables are intellectual rather than physical property, that method is also difficult.[107] Any prosecution of Assange would require extraditing him to the United States, a procedure made more complicated and potentially delayed by any preceding extradition to Sweden.[108] One of Assange's lawyers, however, says they are fighting extradition to Sweden because it might result in his extradition to the United States.[109] Assange's attorney, Mark Stephens, has "heard from Swedish authorities there has been a secretly empanelled grand jury in Alexandria [Virginia]" meeting to consider criminal charges for the WikiLeaks case.[110]

In Australia, the government and the Australian Federal Police have not stated what Australian laws may have been violated by WikiLeaks, but then Prime Minister Julia Gillard has stated that the foundation of WikiLeaks and the stealing of classified documents from the US administration is illegal in foreign countries.[111] Gillard later clarified her statement as referring to "the original theft of the material by a junior US serviceman rather than any action by Mr Assange."[112] Spencer Zifcak, president of Liberty Victoria, an Australian civil liberties group, notes that without a charge or a trial completed, it is inappropriate to state that WikiLeaks is guilty of illegal activities.[113]

On threats by various governments towards Julian Assange, legal expert Ben Saul argues that Assange is the target of a global smear campaign to demonise him as a criminal or as a terrorist, without any legal basis.[114] The U.S. Center for Constitutional Rights has issued a statement emphasising its alarm at the "multiple examples of legal overreach and irregularities" in his arrest.[115]

Wikileaks defence team

The WikiLeaks defence team is led by former Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón and composed of more than sixty lawyers, including Amal Clooney, Gareth Pierce, Jennifer Robinson (United Kingdom), and Michael Ratner (United States).

Financing

WikiLeaks is a not-for-profit organisation, funded largely by volunteers, and it is dependent on public donations. Its main financing methods include conventional bank transfers and online payment systems. Annual expenses have been estimated at about €200,000, mainly for servers and dealing with bureaucracy, but might reportedly become €600,000 if work currently done by volunteers were to become paid.[45]

WikiLeaks' lawyers often work pro bono, and in some cases legal aid has been donated by media organisations such as the Associated Press, the Los Angeles Times, and the National Newspaper Publishers Association.[45] WikiLeaks' only revenue consists of donations, but it has considered other options including auctioning early access to documents.[45] During September 2011, WikiLeaks began auctioning items on eBay to raise funds, and Assange told an audience at Sydney's Festival of Dangerous Ideas that the organisation might not be able to survive.

Funding model

The Wau Holland Foundation helps to process donations to WikiLeaks. In July 2010, the Foundation stated that WikiLeaks was not receiving any money for personnel costs, only for hardware, travelling and bandwidth.[116] An article in TechEye stated:

As a charity accountable under German law, donations for WikiLeaks can be made to the foundation. Funds are held in escrow and are given to WikiLeaks after the whistleblower website files an application containing a statement with proof of payment. The foundation does not pay any sort of salary nor give any renumeration [sic] to WikiLeaks' personnel, corroborating the statement of the site's former German representative Daniel Schmitt [real name Daniel Domscheit-Berg][117] on national television that all personnel works voluntarily, even its speakers.[116]

However, in December 2010 the Wau Holland Foundation stated that 4 permanent employees, including Julian Assange, had begun to receive salaries.[118]

In 2010, Assange said the organisation was registered as a library in Australia, a foundation in France, and a newspaper in Sweden, and that it also used two United States-based non-profit 501c3 organisations for funding purposes.[119]

On 24 December 2009, WikiLeaks announced that it was experiencing a shortage of funds[120] and suspended all access to its website except for a form to submit new material.[121] Material that was previously published was no longer available, although some could still be accessed on unofficial mirror websites.[122] WikiLeaks stated on its website that it would resume full operation once the operational costs were paid.[121] WikiLeaks saw this as a kind of work stoppage "to ensure that everyone who is involved stops normal work and actually spends time raising revenue".[45] While the organisation initially planned for funds to be secured by 6 January 2010,[123] it was not until 3 February 2010 that WikiLeaks announced that its minimum fundraising goal had been achieved.[124]

On 22 January 2010, the internet payment intermediary PayPal suspended WikiLeaks' donation account and froze its assets. WikiLeaks said that this had happened before, and was done for "no obvious reason".[125] The account was restored on 25 January 2010.[126] On 18 May 2010, WikiLeaks announced that its website and archive were operational again.[127]

In June 2010, WikiLeaks was a finalist for a grant of more than half a million dollars from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation,[25] but did not make the final approval.[128] WikiLeaks commented via Twitter, "WikiLeaks was highest rated project in the Knight challenge, strongly recommended to the board but gets no funding. Go figure."[129] WikiLeaks said that the Knight foundation announced the award to "'12 Grantees who will impact future of news' – but not WikiLeaks" and questioned whether Knight foundation was "really looking for impact".[128] A spokesman of the Knight Foundation disputed parts of WikiLeaks' statement, saying "WikiLeaks was not recommended by Knight staff to the board."[129] However, he declined to say whether WikiLeaks was the project rated highest by the Knight advisory panel, which consists of non-staffers, among them journalist Jennifer 8. Lee, who has done PR work for WikiLeaks with the press and on social networking websites.[129]

During 2010, WikiLeaks received €635,772.73 in PayPal donations, less €30,000 in PayPal fees, and €695,925.46 in bank transfers. €500,988.89 of the sum was received in the month of December, primarily as bank transfers as PayPal suspended payments 4 December. €298,057.38 of the remainder was received in April.[130]

The Wau Holland Foundation, one of the WikiLeaks' main funding channels, stated that they received more than €900,000 in public donations between October 2009 and December 2010, of which €370,000 has been passed on to WikiLeaks. Hendrik Fulda, vice president of the Wau Holland Foundation, mentioned that the Foundation had been receiving twice as many donations through PayPal as through normal banks, before PayPal's decision to suspend WikiLeaks' account. He also noted that every new WikiLeaks publication brought "a wave of support", and that donations were strongest in the weeks after WikiLeaks started publishing leaked diplomatic cables.[131][132]

The Icelandic judiciary decided that Valitor (a company related to Visa and MasterCard) was violating the law when it prevented donation to the site by credit card. A justice ruled that the donations will be allowed to return to the site after 14 days or they would be fined in the amount of US$6,000 a day.[133]

Bitcoin adoption

On 15 June 2011, WikiLeaks began accepting donations in bitcoin.[134][135]

Leaks

2006–08

WikiLeaks posted its first document in December 2006, a decision to assassinate government officials signed by Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys.[25] In August 2007, the UK newspaper The Guardian published a story about corruption by the family of the former Kenyan leader Daniel arap Moi based on information provided via WikiLeaks.[136] In November 2007, a March 2003 copy of Standard Operating Procedures for Camp Delta detailing the protocol of the U.S. Army at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp was released.[137][138] The document revealed that some prisoners were off-limits to the International Committee of the Red Cross, something that the U.S. military had in the past denied repeatedly.[139] In February 2008, WikiLeaks released allegations of illegal activities at the Cayman Islands branch of the Swiss Bank Julius Baer, which resulted in the bank suing WikiLeaks and obtaining an injunction which temporarily suspended the operation of wikileaks.org.[140] The California judge had the service provider of WikiLeaks block the site's domain (wikileaks.org) on 18 February 2008, although the bank only wanted the documents to be removed but WikiLeaks had failed to name a contact. The website was instantly mirrored by supporters, and later that month the judge overturned his previous decision citing First Amendment concerns and questions about legal jurisdiction.[141][142] In March 2008, WikiLeaks published what they referred to as "the collected secret 'bibles' of Scientology", and three days later received letters threatening to sue them for breach of copyright.[143] In September 2008, during the 2008 United States presidential election campaigns, the contents of a Yahoo account belonging to Sarah Palin (the running mate of Republican presidential nominee John McCain) were posted on WikiLeaks after being hacked into by members of a group known as Anonymous.[144][145] In November 2008, the membership list of the far-right British National Party was posted to WikiLeaks, after appearing briefly on a weblog.[146] A year later, in October 2009, another list of BNP members was leaked.[147]

2009

In January 2009, WikiLeaks released 86 telephone intercept recordings of Peruvian politicians and businessmen involved in the 2008 Peru oil scandal.[148] During February, WikiLeaks released 6,780 Congressional Research Service reports[149] followed in March by a list of contributors to the Norm Coleman senatorial campaign[150][151] and a set of documents belonging to Barclays Bank that had been ordered removed from the website of The Guardian.[152] In July, it released a report relating to a serious nuclear accident that had occurred at the Iranian Natanz nuclear facility in 2009.[153] Later media reports have suggested that the accident was related to the Stuxnet computer worm.[154][155] In September, internal documents from Kaupthing Bank were leaked, from shortly before the collapse of Iceland's banking sector, which caused the 2008–2012 Icelandic financial crisis. The document shows that suspiciously large sums of money were loaned to various owners of the bank, and large debts written off.[156] In October, Joint Services Protocol 440, a British document advising the security services on how to avoid documents being leaked, was published by WikiLeaks.[157] Later that month, it announced that a super-injunction was being used by the commodities company Trafigura to stop The Guardian (London) from reporting on a leaked internal document regarding a toxic dumping incident in Côte d'Ivoire.[158][159] In November, it hosted copies of e-mail correspondence between climate scientists, although they were not leaked originally to WikiLeaks.[160][161] It also released 570,000 intercepts of pager messages sent on the day of the 11 September attacks.[162][163][164] During 2008 and 2009, WikiLeaks published the alleged lists of forbidden or illegal web addresses for Australia, Denmark and Thailand. These were originally created to prevent access to child pornography and terrorism, but the leaks revealed that other sites featuring unrelated subjects were also listed.[165][166][167]

2010

In mid-February 2010, WikiLeaks received a leaked diplomatic cable from the US Embassy in Reykjavik relating to the Icesave scandal, which they published on 18 February.[168] The cable, known as Reykjavik 13, was the first of the classified documents WikiLeaks published among those allegedly provided to them by US Army Private Chelsea Manning (then known as Bradley). In March 2010, WikiLeaks released a secret 32-page U.S. Department of Defense Counterintelligence Analysis Report written in March 2008 discussing the leaking of material by WikiLeaks and how it could be deterred.[169][170][171] In April, a classified video of the 12 July 2007 Baghdad airstrike was released, showing two Reuters employees being fired at, after the pilots mistakenly thought the men were carrying weapons, which were in fact cameras.[172] After the mistaken killing, the video shows U.S. forces firing on a family van that stopped to pick up the bodies, constituting a war crime.[173] In the week after the release, "wikileaks" was the search term with the most significant growth worldwide during the last seven days as measured by Google Insights.[174] In June 2010, Manning was arrested after alleged chat logs were given to US authorities by former hacker Adrian Lamo, in whom she had confided. Manning reportedly told Lamo she had leaked the "Collateral Murder" video, in addition to a video of the Granai airstrike and about 260,000 diplomatic cables, to WikiLeaks.[175]

In July, WikiLeaks released 92,000 documents related to the war in Afghanistan between 2004 and the end of 2009 to the publications The Guardian, The New York Times and Der Spiegel. The documents detail individual incidents including "friendly fire" and civilian casualties.[176] At the end of July, a 1.4 GB "insurance file" was added to the Afghan War Diary page, whose decryption details would be released if WikiLeaks or Assange were harmed.[84] About 15,000 of the 92,000 documents have not yet been released by WikiLeaks, as the group is currently reviewing the documents to remove some of the sources of the information. WikiLeaks asked the Pentagon and human-rights groups to help remove names from the documents to reduce the potential harm caused by their release, but did not receive assistance.[177] After the Love Parade stampede in Duisburg, Germany, on 24 July 2010, a local resident published internal documents of the city administration regarding the planning of Love Parade. The city government reacted by securing a court order on 16 August forcing the removal of the documents from the website on which it was hosted.[178] On 20 August 2010, WikiLeaks released a publication entitled Loveparade 2010 Duisburg planning documents, 2007–2010, which comprised 43 internal documents regarding the Love Parade 2010.[179][180] After the leak of information concerning the Afghan War, in October 2010, around 400,000 documents relating to the Iraq War were released. The BBC quoted the US Dept. of Defense referring to the Iraq War Logs as "the largest leak of classified documents in its history". Media coverage of the leaked documents emphasised claims that the U.S. government had ignored reports of torture by the Iraqi authorities during the period after the 2003 war.[181]

Diplomatic cables release

On 28 November 2010, WikiLeaks and five major newspapers from Spain (El País), France (Le Monde), Germany (Der Spiegel), the United Kingdom (The Guardian), and the United States (The New York Times) started simultaneously to publish the first 220 of 251,287 leaked documents labelled confidential – but not top-secret – and dated from 28 December 1966 to 28 February 2010.[182][183] WikiLeaks plans to release the entirety of the cables in phases over several months.[183]

The contents of the diplomatic cables include numerous unguarded comments and revelations regarding: critiques and praises about the host countries of various US embassies; political manoeuvring regarding climate change; discussion and resolutions towards ending ongoing tension in the Middle East; efforts and resistance towards nuclear disarmament; actions in the War on Terror; assessments of other threats around the world; dealings between various countries; US intelligence and counterintelligence efforts; and other diplomatic actions. Reactions to the United States diplomatic cables leak varied. On 14 December 2010 the United States Department of Justice issued a subpoena directing Twitter to provide information for accounts registered to or associated with WikiLeaks.[184] Twitter decided to notify its users.[185] The overthrow of the presidency in Tunisia of 2011 has been attributed partly to reaction against the corruption revealed by leaked cables.[186][187][188]

2011–2015

In late April 2011, files related to the Guantanamo prison were released.[189] In December 2011, WikiLeaks started to release the Spy Files.[190] On 27 February 2012, WikiLeaks began publishing more than five million emails from the Texas-headquartered "global intelligence" company Stratfor.[191]

On 5 July 2012, WikiLeaks began publishing the Syria Files, more than two million emails from Syrian political figures, ministries and associated companies, dating from August 2006 to March 2012.[192]

On Thursday, 25 October 2012, WikiLeaks began publishing The Detainee Policies, more than 100 classified or otherwise restricted files from the United States Department of Defense covering the rules and procedures for detainees in U.S. military custody.[193]

In April 2013 WikiLeaks published more than 1.7 million U.S. diplomatic and intelligence documents from the 1970s. These documents included the Kissinger cables.[194]

In September 2013 Dagens Næringsliv said that WikiLeaks, on the previous evening, had published on its website "the whereabouts of 20 chiefs of European surveillance technology companies, during the last year".[195] This was part of WikiLeaks Spy Files 3 project, which was a release of close to[195] 250 documents from more than 90 surveillance companies.

On 13 November 2013 a complete draft of the Trans-Pacific Partnership's Intellectual Property Rights chapter was published by WikiLeaks.[196][197]

On 10 June 2015, WikiLeaks published the complete draft on the Trans-Pacific Partnership's Transparency for Healthcare Annex, along with each country's negotiating position. According to the Sydney Morning Herald, the text of the agreement regulates state schemes for medicines and medical devices and gives big multinational pharmaceutical companies more information and control over national decisions about the health sector.[198]

On 19 June 2015 WikiLeaks began publishing The Saudi Cables: more than half a million cables and other documents from the Saudi Foreign Ministry that contain secret communications from various Saudi Embassies around the world.[199]

On 23 June 2015, WikiLeaks published documents under the name of "Espionnage Élysée", which showed that NSA spied on French government, including but not limited to the current President Francois Hollande and his predecessors Nicolas Sarkozy and Jacques Chirac.[200] Oh 29 June 2015, WikiLeaks published more NSA top secrets intercepts regarding France, detailing an economic espionage against French companies and associations.[201]

In July 2015, WikiLeaks published documents which showed that the NSA had tapped the telephones of many German federal ministries, including that of the Chancellor Angela Merkel, for years since the 1990s.[202]

On 4 July 2015, WikiLeaks published documents which showed that 29 Brazilian government numbers were selected for secret espionage by the NSA. Among the targets there were also the President Dilma Rousseff, many assistants and advisors, her presidential jet and other key figures in the Brazilian government.[203]

On 29 July 2015, WikiLeaks published a top secret letter from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) Ministerial Meeting in December 2013 which illustrated the position of negotiating countries on "state-owned enterprises" (SOEs), and the set of restrictions and regulations against them, aiming to favour the transnational corporations.[204]

On 31 July 2015, WikiLeaks published secret intercepts and the related target list showing that the NSA spied on Japanese government, including the Cabinet and Japanese companies such as Mitsubishi and Mitsui. The documents revealed that US espionage against Japan concerned broad sections of communications about the US-Japan diplomatic relationship and Japan's position on climate change issues, other than an extensive monitoring of the Japanese economy.[205]

On 21 October 2015 WikiLeaks published some of John O. Brennan's emails, including a draft security clearance application which contained personal information.[206]

2016

On 4 July 2016, WikiLeaks tweeted a link to a trove of emails sent or received by then-US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and released under the Freedom of Information Act.[207] The link contained 1258 emails sent from Clinton's personal mail server which were selected in terms of their relevance to the Iraq War and were apparently timed to precede the release of the UK government's Iraq Inquiry report.[208]

On 19 July 2016, WikiLeaks released 294,548 emails from Turkey's ruling Justice and Development party (AKP).[209] According to WikiLeaks, the material, which they claim to be the first batch from the "AKP Emails", was obtained a week before the attempted coup in the country and "is not connected, in any way, to the elements behind the attempted coup, or to a rival political party or state".[210] After WikiLeaks announced that they would release the emails, the organisation stayed for over 24 hours under a "sustained attack".[211][212] Following the leak, the Turkish government ordered the site to be blocked nationwide.[213][214][215][216] The leak included no emails from Erdogan or his inner circle, but did contain, among other sensitive data, spreadsheets with private information of nearly every female voter in Turkey, including for many their Turkish Identification Number.[217] This information was not in the files uploaded directly by WikiLeaks, but was in a link that they sent out to their followers on social media.[218][219]

On 22 July 2016, WikiLeaks released approximately 20,000 emails and 8,000 files sent from or received by Democratic National Committee (DNC) personnel.[220] Some of the emails contained personal information of donors, including home addresses and Social Security numbers.[221] Other emails appeared to criticize Bernie Sanders and showed apparent favouritism towards Clinton.[222][223]

On 7 October 2016, WikiLeaks started releasing series of emails and documents sent from or received by Hillary Clinton campaign manager John Podesta, including Hillary Clinton's paid speeches to banks.[224][225][226][227] According to a spokesman for the Clinton campaign, "By dribbling these out every day WikiLeaks is proving they are nothing but a propaganda arm of the Kremlin with a political agenda doing Putin's dirty work to help elect Donald Trump."[228] The New York Times reported that when asked, president Vladimir Putin replied that Russia was being falsely accused. "The hysteria is merely caused by the fact that somebody needs to divert the attention of the American people from the essence of what was exposed by the hackers."[229][230]

On 17 October 2016 WikiLeaks announced that a "state party" had severed the internet connection of Julian Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy. WikiLeaks blamed United States Secretary of State John Kerry of pressuring the Ecuadorian government in severing Assange's internet, an accusation which the United States State Department denied.[231] The Ecuadorian government stated that it had "temporarily" severed Assange's internet connection because of WikiLeaks' release of documents "impacting on the U.S. election campaign," although it also stated that this was not meant to prevent WikiLeaks from operating.[232]

Announcements of upcoming leaks

In May 2010, WikiLeaks said it had video footage of a massacre of civilians in Afghanistan by the US military which they were preparing to release.[233][234]

In an interview with Chris Anderson on 19 July 2010, Assange showed a document WikiLeaks had on an Albanian oil-well blowout, and said they also had material from inside British Petroleum,[235] and that they were "getting enormous quantity of whistle-blower disclosures of a very high calibre" but added that they had not been able to verify and release the material because they did not have enough volunteer journalists.[236]

In October 2010, Assange told a major Moscow newspaper that "The Kremlin had better brace itself for a coming wave of WikiLeaks disclosures about Russia".[237][238] Assange later clarified: "we have material on many businesses and governments, including in Russia. It's not right to say there's going to be a particular focus on Russia".[239]

In a 2009 interview by the magazine Computerworld, Assange claimed to be in possession of "5GB from Bank of America". In 2010, he told Forbes magazine that WikiLeaks was planning another "megaleak" early in 2011, from the private sector, involving "a big U.S. bank" and revealing an "ecosystem of corruption". Bank of America's stock price decreased by 3%, apparently as a result of this announcement.[240][241] Assange commented on the possible effect of the release that "it could take down a bank or two".[242][243] In August 2011, Reuters announced that Daniel Domscheit-Berg had destroyed approximately 5GB of data cache from Bank of America, that Assange had under his control.[244]

In December 2010, Assange's lawyer, Mark Stephens, told The Andrew Marr Show on BBC Television that WikiLeaks had information it considered to be a "thermo-nuclear device" which it would release if the organisation needs to defend itself against the authorities.[245]

In January 2011, Rudolf Elmer, a former Swiss banker, passed data containing account details of 2,000 prominent people to Assange, who stated that the information will be vetted before being made publicly available at a later date.[246]

Authenticity

Columnist Eric Zorn wrote in 2016 that "it's possible, even likely, that every stolen email WikiLeaks has posted has been authentic."[247] (Writer Glenn Greenwald goes further, asserting that WikiLeaks has a "perfect, long-standing record of only publishing authentic documents."[248]) However, cybersecurity experts agree that it is trivially easy for a person to fabricate an email or alter it, as by changing headers and metadata.[247] Some of the more recent releases, such as many of the emails contained in the Podesta emails, contain DKIM headers. This allows them to be verified as genuine to some degree of certainty.[249]

In July 2016, the Aspen Institute's Homeland Security Group, a bipartisan counterterrorism organization, warned that hackers who stole authentic data might "salt the files they release with plausible forgeries."[247] Russian intelligence agencies have frequently used disinformation tactics, "which means carefully faked emails might be included in the WikiLeaks dumps. After all, the best way to make false information believable is to mix it in with true information."[250]

Other activities

In 2013, the organisation assisted Edward Snowden (who is responsible for the 2013 mass surveillance disclosures) in leaving Hong Kong. Sarah Harrison, a WikiLeaks activist, accompanied Snowden on the flight. Scott Shane of The New York Times stated that the WikiLeaks involvement "shows that despite its shoestring staff, limited fund-raising from a boycott by major financial firms, and defections prompted by Mr. Assange's personal troubles and abrasive style, it remains a force to be reckoned with on the global stage."[251]

Controversially, WikiLeaks announced a reward of an additional $20,000 for information leading to a conviction regarding the death of Seth Rich.[252] This lead some observers to speculate that Seth Rich may have been a WikiLeaks source.[252][253][254]

Internal conflicts

Restructuring

WikiLeaks restructured its process for contributions after its first document leaks did not gain much attention. Assange stated this was part of an attempt to take the voluntary efforts typically seen in "Wiki" projects, and "redirect it to...material that has real potential for change."[255] Some sympathisers were unhappy when WikiLeaks ended a community-based wiki format in favour of a more centralised organisation. The "about" page originally read:[256]

To the user, WikiLeaks will look very much like Wikipedia. Anybody can post to it, anybody can edit it. No technical knowledge is required. Leakers can post documents anonymously and untraceably. Users can publicly discuss documents and analyze their credibility and veracity. Users can discuss interpretations and context and collaboratively formulate collective publications. Users can read and write explanatory articles on leaks along with background material and context. The political relevance of documents and their verisimilitude will be revealed by a cast of thousands.

However, WikiLeaks established an editorial policy that accepted only documents that were "of political, diplomatic, historical or ethical interest" (and excluded "material that is already publicly available").[257] This coincided with early criticism that having no editorial policy would drive out good material with spam and promote "automated or indiscriminate publication of confidential records".[258] The original FAQ is no longer in effect, and no one can post or edit documents on WikiLeaks. Now, submissions to WikiLeaks are reviewed by anonymous WikiLeaks reviewers, and documents that do not meet the editorial criteria are rejected. By 2008, the revised FAQ stated that "Anybody can post comments to it. [...] Users can publicly discuss documents and analyse their credibility and veracity."[259] After the 2010 reorganisation, posting new comments on leaks was no longer possible.[31]

Defections

Within WikiLeaks, there has been public disagreement between founder and spokesperson Julian Assange and Daniel Domscheit-Berg, the website's former German representative who was suspended by Assange. Domscheit-Berg announced on 28 September 2010 that he was leaving the organisation due to internal conflicts over management of the website.[117][260][261]

On 25 September 2010, after being suspended by Assange for "disloyalty, insubordination and destabilization", Daniel Domscheit-Berg, the German spokesman for WikiLeaks, told Der Spiegel that he was resigning, saying "WikiLeaks has a structural problem. I no longer want to take responsibility for it, and that's why I am leaving the project."[262][263][264] Assange accused Domscheit-Berg of leaking information to Newsweek, claiming the WikiLeaks team was unhappy with Assange's management and handling of the Afghan war document releases.[264] Daniel Domscheit-Berg wanted greater transparency in the articles released to the public. Another vision of his was to focus on providing technology that allowed whistle-blowers to protect their identity as well as a more transparent way of communicating with the media, forming new partnerships and involving new people.[265] Domscheit-Berg left with a small group to start OpenLeaks, a new leak organisation and website with a different management and distribution philosophy.[262][266]

While leaving, Daniel Domscheit-Berg copied and then deleted roughly 3,500 unpublished documents from the WikiLeaks servers,[267] including information on the US government's 'no-fly list' and inside information from 20 right-wing organisations, and according to a WikiLeaks statement, 5 gigabytes of data relating to Bank of America, the internal communications of 20 neo-Nazi organisations and US intercept information for "over a hundred internet companies".[268] In Domscheit-Berg's book he wrote: "To this day, we are waiting for Julian to restore security, so that we can return the material to him, which was on the submission platform."[269] In August 2011, Domscheit-Berg claims he permanently deleted the files "in order to ensure that the sources are not compromised."[270]

Herbert Snorrason, a 25-year-old Icelandic university student, resigned after he challenged Assange on his decision to suspend Domscheit-Berg and was bluntly rebuked.[264] Iceland MP Birgitta Jónsdóttir also left WikiLeaks, citing lack of transparency, lack of structure, and poor communication flow in the organisation.[271] According to the periodical The Independent (London), at least a dozen key supporters of WikiLeaks left the website during 2010.[272]

Non-disclosure agreements

Those working for Wikileaks are reportedly required to sign sweeping non-disclosure agreements covering all conversations, conduct, and material, with Assange having sole power over disclosure.[273] The penalty for non-compliance in one such agreement was reportedly £12 million.[273] Wikileaks has been challenged for this practice, as it seen to be hypocritical for an organization dedicated to transparency to limit the transparency of its inner workings and limit the accountability of powerful individuals in the organization.[273][274][275]

Reception

WikiLeaks has received praise as well as criticism. The organisation has won a number of awards, including The Economist's New Media Award in 2008 at the Index on Censorship Awards[276] and Amnesty International's UK Media Award in 2009.[277][278] In 2010, the New York Daily News listed WikiLeaks first among websites "that could totally change the news,"[279] and Julian Assange received the Sam Adams Award[280] and was named the Readers' Choice for TIME's Person of the Year in 2010.[281] The UK Information Commissioner has stated that "WikiLeaks is part of the phenomenon of the online, empowered citizen."[282] During its first days, an Internet petition in support of WikiLeaks attracted more than six hundred thousand signatures.[283] Sympathisers of WikiLeaks in the media and academia have commended it for exposing state and corporate secrets, increasing transparency, assisting freedom of the press, and enhancing democratic discourse while challenging powerful institutions.[284][285][286][287][288][289][290]

At the same time, several U.S. government officials have criticised WikiLeaks for exposing classified information and claimed that the leaks harm national security and compromise international diplomacy.[291][292][293][294][295] Several human rights organisations requested with respect to earlier document releases that WikiLeaks adequately redact the names of civilians working with international forces, in order to prevent repercussions.[296] Some journalists have likewise criticised a perceived lack of editorial discretion when releasing thousands of documents at once and without sufficient analysis.[297] In 2016, Harvard law professor and Electronic Frontier Foundation board member Jonathan Zittrain argued that a culture in which one constantly risks being "outed" as a result of virtual Watergate-like break-ins (or 4th amendment violations) could lead people to hesitate to speak their minds.[298]

In 2010, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights expressed concern over the "cyber war" being led at the time against WikiLeaks,[299] and in a joint statement with the Organization of American States the UN Special Rapporteur called on states and other people to keep international legal principles in mind.[300] According to the US state-run Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, WikiLeaks is motivated by "a theory of anarchy", not a theory of journalism or social activism.[301]

Allegations of anti-Americanism and partisanship

Short of simply disclosing information in the public interest, Wikileaks has been accused of purposely targeting certain states and people, and presenting its disclosures in misleading and conspiratorial ways to harm those people.[302] Writing in 2012, Foreign Policy's Joshua Keating noted that "nearly all its major operations have targeted the U.S. government or American corporations."[303] In the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Assange only exposed material damaging to the Democratic National Committee and Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.

Criticism of Wikileaks' promotion of conspiracy theories

Wikileaks also repeatedly promoted false and unsubstantiated conspiracies about the Democratic Party and Hillary Clinton, such as suggesting that Clinton campaign chairperson John Podesta engaged in satanic rituals,[302][304][305] implying that the Democratic Party had Seth Rich killed,[306] suggesting that Clinton wore earpieces to debates and interviews,[307] claiming that Hillary Clinton wanted to drone strike Assange,[308] and promoting a conspiracy theory from a Donald Trump-related internet community tying the Clinton campaign to child kidnapper Laura Silsby.[309] According to Harvard political scientist Matthew Baum and College of the Canyons political scientist Phil Gussin, Wikileaks strategically released e-mails related to the Clinton campaign whenever Clinton's lead expanded in the polls.[310]

Allegations of a potential smear campaign against WikiLeaks

In 2011, hacktivist group Anonymous published secret plans presented by Palantir Technologies to US intelligence to attempt to discredit WikiLeaks with smear campaigns and systematic attacks against WikiLeaks.[311] Bank of America, Berico Technologies, HBGary, Hunton & Williams, were also allegedly involved in those proposed plans.[312][313][314][315] The New York Times reported that the plan presented by Palantir Technologies had been pitched to a Washington law firm by a Palantir employee, that the employee was temporarily suspended, and that a Palantir spokesperson claimed it would have collapsed if it had tried to carry out the plan.[311]

Allegations of Russian influence

In August 2016, after Wikileaks published thousands of DNC emails, it was claimed that Russian intelligence had hacked the e-mails and leaked them to Wikileaks. At the time, DNC officials made such claims, along with a number of cybersecurity experts and cybersecurity firms.[316][317] In October 2016, the U.S. intelligence community announced that it was "confident that the Russian Government directed the recent compromises of e-mails from US persons and institutions, including from US political organizations".[318] The U.S. intelligence agencies said that the hacks were consistent with the methods of Russian-directed efforts, and that people high up within the Kremlin were likely involved.[318] On 14 October 2016, CNN reported that "there is mounting evidence that the Russian government is supplying WikiLeaks with hacked emails pertaining to the US presidential election."[319] WikiLeaks has denied any connection to or cooperation with Russia.[319] President Putin has strongly denied any Russian involvement.[229][230]

In September 2016, the German weekly magazine Focus reported that according to a confidential German government dossier, WikiLeaks had long since been infiltrated by Russian agents aiming to discredit NATO governments. The magazine added that French and British intelligence services had come to the same conclusion and said Russian President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev receive details about what WikiLeaks publishes before publication.[320][321] The Focus report followed a New York Times story that suggested that WikiLeaks may be a laundering machine for compromising material about Western countries gathered by Russian spies.[322]

Allegations of anti-semitism

Wikileaks has been accused of anti-semitism.[323][324][325][326] The Wikileaks Twitter account tweeted anti-semitic jibes.[325][326] The organization has called out Jewish "lobbies" and claimed that a "Jewish conspiracy" is attempting to discredit the organization.[323][327] In July 2016, Wikileaks suggested that the parentheses bracketing, or (((echoes))) — a tool used by neo-Nazis to identify Jews on Twitter, appropriated by Jews across the Twittersphere — had been used as a way for "establishment climbers" to identify one another.[324][326] Assange denied making claims of a Jewish conspiracy, stating, "'Jewish conspiracy' is completely false, in spirit and in word. It is serious and upsetting.”[323]

Inadequate curation and violations of personal privacy

In July 2016, Edward Snowden criticized Wikileaks for insufficiently curating its content.[328] When Snowden made data public, he did so by working with the Washington Post, the Guardian and other news organizations, chosing only to make documents public which exposed National Security Agency surveillance programs.[328] Content that compromised national security or exposed sensitive personal information was withheld.[328] Wikileaks, on the other hand, makes little effort to remove sensitive personal information or withhold content with adverse national security implications. Wikileaks responded by accusing Snowden of pandering to Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton.[328]

University of North Carolina Professor Zeynep Tufekci has criticized Wikileaks for exposing sensitive personal information: "WikiLeaks, for example, gleefully tweeted to its millions of followers that a Clinton Foundation employee had attempted suicide... Data dumps by WikiLeaks have outed rape victims and gay people in Saudi Arabia, private citizens’ emails and personal information in Turkey, and the voice mail messages of Democratic National Committee staff members."[329] She argues these data dumps which violate personal privacy without being in the public interest "threaten our ability to dissent by destroying privacy and unleashing a glut of questionable information that functions, somewhat unexpectedly, as its own form of censorship, rather than as a way to illuminate the maneuverings of the powerful."[329]

Spin-offs

Release of US diplomatic cables was followed by the creation of a number of other organisations based on the WikiLeaks model.[330]

- OpenLeaks was created by a former WikiLeaks spokesperson. Daniel Domscheit-Berg said the intention was to be more transparent than WikiLeaks. OpenLeaks was supposed to start public operations in early 2011 but despite much media coverage, as of April 2013 it is not operating.

- In December 2011, WikiLeaks launched Friends of WikiLeaks, a social network for supporters and founders of the website.[331]

- On 9 September 2013 [332] a number of major Dutch media outlets supported the launch of Publeaks, which provides a secure website for people to leak documents to the media using the GlobaLeaks whistleblowing software.[333]

- RuLeaks is aimed at being a Russian equivalent to WikiLeaks. It was initiated originally to provide translated versions of the WikiLeaks cables but the Moscow Times reports it has started to publish its own content as well.[334]

- Leakymails is a project designed to obtain and publish relevant documents exposing corruption of the political class and the powerful in Argentina.[335][336][337]

- Honest Appalachia,[338] initiated in January 2012, is a website based in the United States intended to appeal to potential "whistleblowers" in West Virginia, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee and North Carolina, and serve as a replicable model for similar projects elsewhere.[339][340]

In popular culture

A thriller about WikiLeaks was released in the United States on 18 October 2013. The documentary We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks by director Alex Gibney premiered at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival.[341]

War, lies and videotape is a documentary by French directors Paul Moreira and Luc Hermann from press agency Premieres Lignes. The film was first released in France, in 2011 and then broadcast worldwide.[342]

See also

- 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak

- Accountability

- Anonymous (group)

- Chilling Effects

- Classified information in the United States

- Digital rights

- Freedom of information

- Freedom of the press

- Freedom of the Press Foundation

- GlobaLeaks

- Information security

- New York Times Co. v. United States

- Open society

- 1993 PGP Criminal investigation

- Transparency (social)

References

- ↑ "WikiLeaks' official Twitter account". Archived from the original on 26 July 2010.

- ↑ "Wikileaks Mirrors". WikiLeaks. 24 August 2012. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ "Wikileaks.org Site Info". Alexa Internet. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ "About". WikiLeaks. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- 1 2 "Whois Search Results: wikileaks.org". GoDaddy. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Karhula, Päivikki (5 October 2012). "What is the effect of WikiLeaks for Freedom of Information?". International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Editors, The (16 August 2012). "WikiLeaks – The New York Times". Topics.nytimes.com. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ Chatriwala, Omar (5 April 2010). "WikiLeaks vs the Pentagon". Al Jazeera blog. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ↑ "Wikileaks has 1.2 million documents?". WikiLeaks. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ↑ McGreal, Chris (5 April 2010). "Wikileaks reveals video showing US air crew shooting down Iraqi civilians". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Mostrous, Alexi (4 August 2011). "He came for a week and stayed a year". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012.(subscription required)

- ↑ "Wikileaks sets up shop in Iceland – Heated pavements far nicer than Gitmo TechEye". Archived from the original on 10 February 2014.. News.techeye.net (15 November 2010). Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ "Wikileaks starts company in Icelandic apartment IceNews – Daily News". Archived from the original on 22 November 2010.. Icenews.is (13 November 2010). Retrieved 22 November 2011. WikiLeaks is not and never has been affiliated with the well-known website Wikipedia or Wikipedia's parent organization, the Wikimedia Foundation.

- ↑ Channing, Joseph (9 September 2007). "Wikileaks Releases Secret Report on Military Equipment". The New York Sun. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks to publish new documents". MSNBC. Associated Press. 7 August 2010. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ↑ Rogers, Simon (23 October 2010). "Wikileaks Iraq: data journalism maps every death". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Rogers, Simon (25 October 2010). "Wikileaks Iraq: what's wrong with the data?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Leigh, David; Ball, James; Burke, Jason (25 April 2011). "Guantánamo files lift lid on world's most controversial prison". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ↑ "Guardian journalist negligently disclosed Cablegate passwords". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.. Wikileaks.org. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ↑ Ball, James (1 September 2011). "WikiLeaks prepares to release unredacted US cables Media guardian.co.uk". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013.. Guardian. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ↑ "Leak at WikiLeaks: A Dispatch Disaster in Six Acts – SPIEGEL ONLINE – News – International". Archived from the original on 7 November 2011.. Spiegel.de. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ↑ "Exposed: Uncensored WikiLeaks cables posted to Web". Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Raphael G. Satter, Associated Press, 1 September 2011, At Physorg.com

- ↑ "WikiLeaks Blames Newspaper for Uncensored Cable Leak". Archived from the original on 21 April 2012. Voice of America, 1 September 2011

- ↑ Calabresi, Massimo (2 December 2010). "WikiLeaks' War on Secrecy: Truth's Consequences". Time. New York. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

Reportedly spurred by the leak of the Pentagon papers, Assange unveiled WikiLeaks in December 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 Khatchadourian, Raffi (7 June 2010). "No Secrets: Julian Assange's Mission for total transparency". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ↑ Guilliatt, Richard (30 May 2009). "Rudd Government blacklist hacker monitors police". The Australian. Sydney. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ Burns, John F.; Somaiya, Ravi (23 October 2010). "WikiLeaks Founder on the Run, Trailed by Notoriety". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- 1 2 "About WikiLeaks". WikiLeaks. 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ Rintoul, Stuart (9 December 2010). "WikiLeaks advisory board 'pretty clearly window-dressing'". The Australian. Sydney. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ↑ "Inside WikiLeaks' Leak Factory". Archived from the original on 29 April 2014.. Mother Jones (6 April 2010). Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- 1 2 Gilson, Dave (19 May 2010). "WikiLeaks Gets A Facelift". Mother Jones. San Francisco. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ Wackywace, HaeB, and Tony1 (6 September 2010). "Difficult relationship between WikiLeaks and Wikipedia". The Signpost. Wikipedia. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Wikipedia:WikiLeaks is not part of Wikipedia". Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Rawlinson, Kevin; Peck, Tom (30 August 2010). "Wiki giants on a collision course over shared name". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Press:Wikia Does Not Own Wikileaks Domain Names". Wikia. Wikia. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ↑ "EPIC v. DOJ, FBI: Wikileaks". Electronic Privacy Information Center. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014.

- ↑ "Exclusive – Julian Assange Extended Interview". Colbert Nation. 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011.

- 1 2 Bradner, Scott (17 January 2007). "Wikileaks: a site for exposure". Network World. Framingham, MA. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ↑ "How to be a Whistle Blower". Unknowncountry.com. 17 January 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ↑ "Global journalists' union supports Wikileaks". Alliance.org.au. 16 July 2013. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ↑ David Dishneau, Harvard prof is star witness at WikiLeaks trial, Associated Press (13 July 2016).

- ↑ Rainey Reitman, Transcript: Yochai Benkler Testifies at Bradley Manning Trial, Freedom of the Press Foundation (10 July 2013).

- 1 2 Kelly McBridge, "What Is WikiLeaks? That's the Wrong Question" in Page One: Inside the New York Times and the Future of Journalism (ed. David Folkenflik: PublicAffairs, 2011).

- 1 2 Floyd Abrams, Friend of the Court: On the Front Lines with the First Amendment (Yale University Press, 2013), p. 390.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mey, Stefan (4 January 2010). "Leak-o-nomy: The Economy of Wikileaks (Interview with Julian Assange)". Medien-Ökonomie-Blog. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ↑ "Supporters". Wikileaks. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014.

- ↑ Dorling, Philip. "Building on WikiLeaks". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ↑ Marsh, Heather. "To Whom It May Concern". WL Central. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ Moss, Stephen (14 July 2010). "Julian Assange: the whistleblower". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ↑ Satter, Raphael G.; Peter Svensson (3 December 2010). "WikiLeaks fights to stay online amid attacks". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ↑ Randall, David; Cooper, Charlie (5 December 2010). "WikiLeaks hit by new online onslaught". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- 1 2 Goodwin, Dan (21 February 2008). "Wikileaks judge gets Pirate Bay treatment". The Register. London. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ↑ "Pentagon-papirer sikret i atom-bunker". VG Nett (in Norwegian). Oslo. 27 August 2010. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ↑ Greenberg, Andy (30 August 2010). "Wikileaks Servers Move To Underground Nuclear Bunker". Forbes (blog). Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- 1 2 Fredén, Jonas (14 August 2010). "Jagad och hatad – men han vägrar vika sig" [Chased and hated – but he refuses to give way]. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Stockholm. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010.

- ↑ Helin, Jan (14 August 2010). "Därför blir Julian Assange kolumnist i Aftonbladet". Aftonbladet (blog) (in Swedish). Stockholm. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ "What is WikiLeaks?". This Just In (CNN blog). 25 July 2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ↑ TT (17 August 2010). "Piratpartiet sköter Wikileak-servrar" [Pirate Party manages Wikileaks Servers]. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Stockholm. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ↑ "Swedish Pirate Party to host WikiLeaks servers". CNN. 18 August 2010. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- 1 2 Gross, Doug (2 December 2010). "WikiLeaks cut off from Amazon servers". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Hennigan, W.J. (2 December 2010). "Amazon says it dumped WikiLeaks because it put innocent people in jeopardy". Technology blog, Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ↑ Poncet, Guerric (3 December 2010). "Expulsé d'Amazon, WikiLeaks trouve refuge en France". Le Point (in French). Paris.

- ↑ "French company allowed to keep hosting WikiLeaks". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Bloomberg L.P. 8 December 2010. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ↑ "French web host need not shut down WikiLeaks site: judge". France 24. AFP. 6 December 2010. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ↑ "Submissions". WikiLeaks. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

You can also use secure TOR network (secure, anonymous, distributed network for maximum security)

- ↑ Archived 22 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "PGP key 0x11015F80 has expired on 2nd November 2007". Archived from the original on 10 July 2011.

- ↑ "Why have WikiLeakS.org abandoned the use of PGP Encryption ?". WikiLeak. Archived from the original on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ↑ "Wikileaks no longer using PGP ? How can the wikileaks editorial team be contacted privately without PGP ?". Wikileaks.org. 22 September 2008. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ↑ "Wikileaks / WL Central". WL Central. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

Between 2006 and October 2010, Wikileaks site was based on an implementation of the Mediawiki software (hence the name, Wikileaks). In October the site was taken down, and when Wikileaks returned, the new site (above) replaced the Mediawiki site.

- ↑ McLachlan, John; Hopper, Nicholas (2009). "On the risks of serving whenever you surf" (PDF). freehaven.net. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ "Julian Assange compte demander l'asile en Suisse". TSR (in French). Geneva. 4 November 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011.

- ↑ Nebehay, Stephanie (4 November 2010). "WikiLeaks founder says may seek Swiss asylum". Reuters. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks-Gründer erwägt Umzug in die Schweiz". ORF (in German). Vienna. 5 November 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks Founder to Release Thousands of Documents on Lebanon". Al-Manar TV. Al-Manar. 5 November 2010. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ↑ Ladurantaye, Steve (8 December 2010). "Canadian firm caught up in Wiki wars". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ↑ "WikiLeaks:Tor". WikiLeaks.

- ↑ WikiLeak (17 July 2010). "WikiLeakS.org again has a Tor Hidden Service for encrypted anonymised uploads - suw74isz7wqzpmgu.onion/".

- ↑ Trapido, Michael (1 December 2010). "Wikileaks: Is Julian Assange a hero, villain or simply dangerously naïve?". NewsTime. Johannesburg. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". WikiLeaks. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- 1 2 Kushner, David (6 April 2010). "Inside WikiLeaks' Leak Factory". Mother Jones. San Francisco. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Afghan War Diary, 2004–2010". WikiLeaks. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ↑ WikiLeaks (19 October 2010). "Now is a good time to mirror this WikiLeaks 'insurance' backup". Twitter. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- 1 2 Zetter, Kim (30 July 2010). "WikiLeaks Posts Mysterious 'Insurance' File". Wired. New York. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Ward, Victoria (3 December 2010). "WikiLeaks website disconnected as US company withdraws support". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- 1 2 Palmer, Elizabeth (2 December 2010). "WikiLeaks Backup Plan Could Drop Diplomatic Bomb". CBS News. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ↑ WikiLeaks (22 February 2012). "Please bittorrent WikiLeaks Insurance release 2012-02-22 (65GB)". Twitter. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ "wikileaks-insurance-20120222.tar.bz2.aes.torrent". wlstorage.net. 22 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ "Official WikiLeaks Facebook Page". facebook.com. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- 1 2 Berkeley, Reno (2016-06-19). "WikiLeaks Issues 'Torrent Insurance' Encrypted File With Dead-Man's Switch". Inquisitr. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- ↑ Dwilson, Stephanie Dube (2016-06-19). "Is the WikiLeaks Insurance File About Hillary Clinton?". Heavy.com. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- ↑ "The Justice Department weighs a criminal case against WikiLeaks". The Washington Post. 18 August 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ↑ WikiRebels the Documentary (Television production). Stockholm: Sveriges Television. December 2010. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. (35:45 to 36:03)

- ↑ "Read closely: NATO tells CNN not a single case of Afghans needing protection or moving due to leak bit.ly/dk5NZi". Twitter. 17 October 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ↑ "Outcomes of WikiLeaks investigation" (Press release). Australian Department of Defence. 26 October 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.