Khan (title)

Khan (Mongolian: хан/khan; Turkish: han or hakan; Azerbaijani: xan; Ottoman: han; Old Turkic: 𐰴𐰍𐰣, kaɣan; Chinese: 可汗, kèhán; Goguryeo : 皆, key; Silla: 干, kan; Baekje: 瑕, ke; Manchu: ᡥᠠᠨ, Pashto: خان Urdu: خان, Balochi: خان Hindi: ख़ान; Nepali: खाँ Bengali: খান; Bulgarian: хан,[1] Chuvash: хун, hun) is originally a title for a sovereign or a military ruler, widely used by medieval nomadic Mongolic and later Turkic tribes living to the north of China. "Khan" also occurs as a title in the Xianbei confederation[2] for their chief between 283 and 289.[3] The Rourans were the first people who used the titles khagan and khan for their emperors.[4] Subsequently the Ashina adopted the title and brought it to the rest of Asia. In the middle of the sixth century the Iranians knew of a "Kagan – King of the Turks".[2]

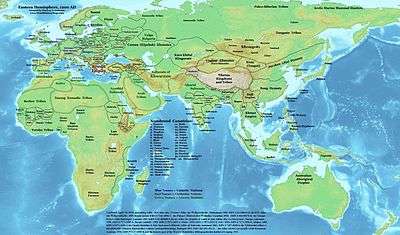

Khan now has many equivalent meanings such as "commander", "leader", or "ruler" "king" "chief". As of 2015 khans exist in South Asia, Middle East, Central Asia, Eastern Europe and Turkey. The female alternatives are Khatun and Khanum. These titles or names are sometimes written as Han, Kan, Hakan, Hanum, or Hatun (in Turkey) and as "xan", "xanım" (in Azerbaijan). Various Mongolic and Turkic peoples from Central Asia gave the title new prominence after period of the Mongol Empire (1206–1368) in the Old World and later brought the title "khan" into Northern Asia, where locals later adopted it. Khagan is rendered as Khan of Khans. It was the title of Chinese Emperor Emperor Taizong of Tang (Heavenly Khagan, reigned 626 to 649), and also the title of Genghis Khan and of the persons selected to rule the Mongol Empire. For instance Möngke Khan (reigned 1251-1259) and Ogedei Khan (reigned 1229-1241) would be "Khagans" but not Chagatai Khan, who was not proclaimed ruler of the Mongol Empire by the kurultai.[5]

Khanate rulers and dynasties

Ruling khans

Originally khans headed only relatively minor tribal entities, generally in or near the vast Mongolian and North Chinese steppe, the scene of an almost endless procession of nomadic people riding out into the history of the neighbouring sedentary regions. Some managed to establish principalities of some importance for a while, as their military might repeatedly proved a serious threat to such empires as China and kingdoms in Central Asia.

One of the earliest notable examples of such principalities in Europe was Danube Bulgaria (presumably also Old Great Bulgaria), ruled by a khan or a kan at least from the 7th to the 9th century. It should be noted that the title "khan" is not attested directly in inscriptions and texts referring to Bulgar rulers – the only similar title found so far, Kanasubigi, has been found solely in the inscriptions of three consecutive Bulgarian rulers, namely Krum, Omurtag and Malamir (a grandfather, son and grandson). Starting from the compound, non-ruler titles that were attested among Bulgarian noble class such as kavkhan (vicekhan), tarkhan, and boritarkhan, scholars derive the title khan or kan for the early Bulgarian leader – if there was a vicekhan (kavkhan) there was probably a "full" khan, too. Compare also the rendition of the name of early Bulgarian ruler Pagan as Καμπαγάνος (Kampaganos), likely resulting from a misinterpretation of "Kan Pagan", in Patriarch Nicephorus's so-called Breviarium[6] In general, however, the inscriptions as well as other sources designate the supreme ruler of Danube Bulgaria with titles that exist in the language in which they are written – archontеs, meaning 'commander or magistrate' in Greek, and knyaze, meaning "duke" or "prince" in Slavic. Among the best known Bulgar khans were: Khan Kubrat, founder of Great Bulgaria; Khan Asparukh, founder of Danubian Bulgaria (today's Bulgaria); Khan Tervel, who defeated the Arab invaders in 718 Siege of Constantinople (718), thus stopped the Arab invasion in Southeast Europe; Khan Krum, "the Terrible". "Khan" was the official title of the ruler until 864 AD, when Kniaz Boris (known also as Tsar Boris I) adopted the Eastern Orthodox faith.

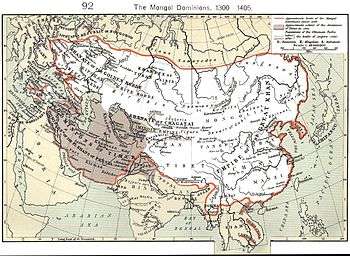

The title Khan became unprecedently prominent when the Mongol Temüjin created the Mongol empire, the greatest land empire the world has ever seen, which he ruled as Genghis Khan. His title was khagan, or "Khan of Khans", but has often been abbreviated to Khan (rather like the Persian Shahanshah -also meaning "King of Kings"- is usually called Shah, equally incorrect, in most Western languages) or described as "Great Khan" (like the Ottoman Padishah being called "Great Sultan"). The great leader was regarded as a khan in the middle east and Asia. Ming Dynasty Chinese Emperors also used the term Xan to denote brave warriors and rulers. The title Khan was used to designate the greatest rulers of the Jurchens, who, later when known as the Manchus, founded the Manchu Qing dynasty.

Once more, there would be numerous khanates in the steppe in and around Central Asia, often more of a people than a territorial state, e.g.:

- of the Kazakhs (founded 1465; since 1601 divided into three geographical Jüz or Hordes, each under a bey; in 1718 split into three different khanates; eliminated by the Russian Empire by 1847)

- in present Uzbekistan, the main khanate, named after its capital Bukhara, was founded in 1500 and restyled emirate in 1753 (after three Persian governors since 1747); the Ferghana (valley's) khanate broke way from it by 1694 and became known as the Khanate of Kokand after its capital Kokand from its establishment in 1732; the khanate of Khwarezm, dating from c.1500, became the Khanate of Khiva in 1804 but fell soon under Russian protectorate; Karakalpakstan had its own rulers (khans?) since c. 1600.

While most Afghan principalities were styled emirate, there was a khanate of ethnic Uzbeks in Badakhshan since 1697.

Khan was also the title of the rulers of various break-away states and principalities later in Persia, e.g. 1747–1808 Khanate of Ardabil (in northwestern Iran east of Sarab and west of the southwest corner of the Caspian Sea), 1747–1813 Khanate of Khoy (northwestern Iran, north of Lake Urmia, between Tabriz and Lake Van), 1747–1829 Khanate of Maku (in extreme northwestern Iran, northwest of Khoy, and 60 miles south of Yerevan, Armenia), 1747–1790s Khanate of Sarab (northwestern Iran east of Tabriz), 1747 – c.1800 Khanate of Tabriz (capital of Iranian Azerbeidjan).

There were various small khanates in and near Transcaucasia and Ciscaucasia established by the Iranian Safavids, or their successive Iranian Afsharid and Qajar dynasties outside their territories of Persia proper. For example, in present Armenia and nearby territories to the left and right, there was the khanate of Erivan (sole incumbent 1807–1827 Hosein Quli Khan Qajar). Diverse khanates existed in Dagestan (now part of Russia), Azerbaijan, including Baku (present capital), Ganja, Jawad, Quba (Kuba), Salyan, Shakki (Sheki, ruler style Bashchi since 1743) and Shirvan=Shamakha (1748–1786 temporarily split into Khoja Shamakha and Yeni Shamakha), Talysh (1747–1814); Nakhichevan and (Nagorno) Karabakh.

As hinted above, the title Khan was also common in some of the polities of the various – generally Islamic – peoples in the territories of the Mongol Golden Horde and its successor states, which, like the Mongols in general, were commonly called Ta(r)tars[7] by Europeans and Russians, and were all eventually subdued by Muscovia which became the Russian Empire. The most important of these states were:

- Khanate of Kazan (the Mongol term khan became active since Genghizide dynasty was settled in Kazan Duchy in 1430s).

- Sibir Khanate (giving its name to Siberia as the first significant conquest during Russia's great eastern expansion across the Ural range)

- Astrakhan Khanate

- Crimean Khanate.

Further east, in Xinjiang flank:

- Khanate of Kashgaria founded in 1514; 17th century divided into several minor khanates without importance, real power going to the so-called Khwaja, Arabic Islamic religious leaders; title changed to Amir Khan in 1873, annexed by China in 1877.

Compound and derived princely titles

The higher, rather imperial title Khaqan ("Khan of Khans") applies to probably the most famous rulers known as Khan: the Mongol imperial dynasty of Genghis Khan (his name was Temüjin, Genghis Khan a never fully understood unique title), and his successors, especially grandson Kublai Khan: the former founded the Mongol Empire and the latter founded the Yuan Dynasty in China. The ruling descendants of the main branch of Genghis Khan's dynasty are referred to as the Great Khans.

The title Khan of Khans was among numerous titles used by the Sultans of the Ottoman empire as well as the rulers of the Golden Horde and its descendant states. The title Khan was also used in the Seljuk Turk dynasties of the near-east to designate a head of multiple tribes, clans or nations, who was below an Atabeg in rank. Jurchen and Manchu rulers also used the title Khan (Han in Manchu); for example, Nurhaci was called Genggiyen Han. Rulers of the Göktürks, Avars and Khazars used the higher title Kaghan, as rulers of distinct nations.

- Gur Khan, meaning supreme or universal Khan, was the ruler of the Khitan Kara-Kitai, and has occasionally been used by the Mongols as well

- Ilkhan, both a generic term for a 'provincial Khan' and traditional royal style for one of the four khanates in Genghis's succession, based in Persia. See the main article for more details.

- Khan-i-Khanan (Persian: خان خانان, "Lord of Lords") was a title given to the commander-in-chief of the army of the Mughals, an example being Abdul Rahim Khan-I-Khana of the great Mughal emperor, Akbar's (and later his son Jahangir's) army.

- Khan Sahib Shri Babi was the complex title of the ruler of the South Asia princely state of Bantva-Manavadar (state founded 1760; September 1947 acceded to Pakistan, but 15 February 1948 forced to rescind accession to Pakistan, to accede to India after Khan Sahib's arrest).

- In southern Korean states, the word Han or Gan, meaning "leader", possibly derived from Khan, was used for various ruling princes, until Silla, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, united them under a now hereditary king, titled Maripgan, meaning the 'head of kings' (e.g. King Naemul Maripgan).

- Khatun, or Khatan (Persian: خاتون) – a title of European Sogdian origin[8][9][10] – is roughly equal to a King's queen in Mongolic and Turkic languages, as by this title a ruling Khan's Queen-consort (wife) is designated with similar respect after their proclamation as Khan and Khatun. Also used in Hazari (instead of Khanum). Famous Khatuns include:

- Khanum (Turkish: Hanım, Azerbaijani: Xanım, Persian: خانم) is another female derivation of Khan, notably in Turkic languages, for a Khan's Queen-consort, or in some traditions extended as a courtesy title (a bit like Lady for women not married to a Lord, which is the situation modern Turkish) to the wives of holders of various other (lower) titles; in Afghanistan, for example, it ended up as the common term for 'Miss', any unmarried woman. In the modern Kazakh language, Khatun is a derogatory term for women, while Khanum has a respectful meaning.

- Khan Bahadur (title) - a compound of khan (leader) and Bahadur (Brave) - was a formal title of respect and honour, which was conferred exclusively on Muslim subjects of the British Indian Empire.[1] It was a title one degree higher than the title of Khan Sahib.

- The compound Galin Khanum – literally, "lady bride" – was the title accorded to the principal noble wife of a Qajar

- Khanzada (Urdu: خانزاده راجپوت) is a title conferred to princes of the dynasties of certain princely states.

- Khaqan or Khakhan (Old Turkic: 𐰴𐰍𐰣, kaɣan)[11] is used as a title in Pakistan.

- Khandan ('Khan holder') means "Family" in Hindustani (ख़ानदान (Devanagari), خاندان (Nastaleeq)).

- Kanasubigi or Kana subigi, as it is written in Bulgarian Greek inscriptions, was a title of the Bulgars. Among the proposed translations for the phrase kanasubigi as a whole are lord of the army, from the reconstructed Turkic phrase *sü begi, paralleling the attested Old Turkic sü baši,[12] and, more recently, "(ruler) from God", from the Indo-European *su- and baga-, i.e. *su-baga (an equivallent of the Greek phrase ὁ ἐκ Θεοῦ ἄρχων, ho ek Theou archon, which is common in Bulgar inscriptions)

- Kavhan[13] or Kaukhan was one of the most important officials in the First Bulgarian Empire. According to the generally accepted opinion, he was the second most important person in the state after the Bulgarian ruler. Owais Khan was also believed a Great Khan but no evidences about him are founded.

- Beg Khan (Baig or Khan) is title used by some Mughals and Mongols like Sultan Mohammed Öz Beg,[14] Adina Beg, etc. and used some Indian Muslim like General people Moazzam Beg Khans[15] is a young editor chief in BeyPeople News (social news).[16]

Other khans

Noble and honorary titles

In imperial Persia, Khan (female form Khanum in Persia) was the title of a nobleman, higher than Beg (or bey) and usually used after the given name. At the Qajar court, precedence for those not belonging to the dynasty was mainly structured in eight classes, each being granted an honorary rank title, the fourth of which was Khan, or in this context synonymously Amir, granted to commanders of armed forces, provincial tribal leaders; in descending order. In neighboring Ottoman Turkey and subsequently the Republic of Turkey, the term Khanum was and is still written as Hanım in Turkish/Ottoman Turkish language. The Ottoman title of Hanımefendi (lit translated; lady of the master), is also a derivative of this.

The titles Khan and Khan Bahadur Mongolic root baghatur, related to the Mongolian baatar ("brave, hero"); were also bestowed in feudal India by the Mughals, who although Muslims were of Mongolian origin upon Muslims and sometimes Hindus, and later by the British Raj, as an honor akin to the ranks of nobility, often for loyalty to the crown. Khan Sahib was another title of honour.

In the major South Asian Muslim state of Hyderabad, Khan was the lowest of the aristocratic titles bestowed by the ruling Nizam upon Muslim retainers, ranking under Khan Bahadur, Nawab (homonymous with a high Muslim ruler's title), Jang, Daula, Mulk, Umara, Jah. The equivalent for the courts Hindu retainers was Rai. In Swat, a Pakistani Frontier State, it was the title of the secular elite, who together with the Mullahs (Muslim clerics), proceeded to elect a new Amir-i-Shariyat in 1914. It seems unclear whether the series of titles known from the Bengal sultanate are merely honorific or perhaps relate to a military hierarchy.

Other uses (surname)

Khan is a surname as well as an honor. Some of the Hindu Brahmins also worked for Mahan Mugal Samrat Akbar (AD 1556) and so Akbar honored them as a Khan. Because of this they are using the last name as Khan, but they still belong to Hindu Brahmins.

Like many titles, the meaning of the term has also extended downwards, such as in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asian nations, where it has become a common surname.

Khan and its female forms occur in many personal names, generally without any nobiliary of political relevance, although it remains a common part of noble names as well. Notably in South Asia it has become a part of many South Asian Muslim names, especially when Pathan descent is claimed. It is also used by many Muslim Rajputs of India and Pakistan were awarded this surname by Turkic Mughals for their bravery.[17] Similarly it was awarded to Pashtuns by Turkic and Mongol kings but also the name is claimed to be related to the Hebrew name Cohen or Kohen. The more plausible explanation is the Hun origin of the Pashtuns. Hun in its original pronunciation is Khun and thus Khan. To this day in India a Pashtun is ordinarilly called Khan Sahib regardless of whether his surname contains that word or not.

During the Russian Civil War following the Bolshevik takeover of 1917, White general Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, who, admittedly was trying to reconstitute the empire of Genghis Khan, was often styled as "Ungern Khan" between 1919 and his death in 1921.

In popular culture, Khan (Khan Noonien Singh) is a villain in the Star Trek universe, typically used as a plot counterweight to Captain James Tiberius Kirk. While not a ruler or nobleman, 'Khan' does have several followers who are, like himself, genetically - modified super soldiers.

Khan-related terms

- Khanzadeh (Tatar: Xanzadä) – a prince, khan's son

- Khanbikeh (Tatar: Xanbikä) – a queen, khan's wife

- Khanbaliq (or Dadu) – Yuan capital which later developed into modern Beijing.

- Yuruk Khans in Ardemush or Erdemuş Village in Kailar. (see: Ottoman Tapu Archivies)

See also

Notes

- ↑ bg:Хан Аспарух (пояснение)

- 1 2 Henning, W. B., 'A Farewell to the Khagan of the Aq-Aqataran',"Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African studies – University of London", Vol 14, No 3, p 501–522

- ↑ Zhou 1985, p. 3–6

- ↑ René Grousset (1988). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia now. Rutgers University Press. pp. 61, 585, n. 92. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Fairbank, John King. The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press, 1978. p. 367

- ↑ Източници за българската история – Fontes historiae bulgaricae. VI. Fontes graeci historiae Bulgaricae. БАН, София. p.305 (in Byzantine Greek and Bulgarian). Also available online

- ↑ The spelling with 'r' is due to a confusion with tartaros, the classical Greek hell. Genghis Khan's conquering, ransacking Mongol hordes terrorized Islam and Christianity without precedent, as if the apocalypse had started.

- ↑ Carter Vaughn Findley, "Turks in World History", Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 45: "... Many elements of Non-Turkic origin also became part of Türk statecraft [...] for example, as in the case of khatun [...] and beg [...] both terms being of Sogdian origin and ever since in common use in Turkish. ..."

- ↑ Fatima Mernissi, "The Forgotten Queens of Islam", University of Minnesota Press, 1993. pg 21: "... Khatun 'is a title of Sogdian origin borne by the wives and female relatives of the Tu-chueh and subsequent Turkish Rulers ..."

- ↑ Leslie P. Peirce, "The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire", Oxford University Press, 1993. pg 312: "... On the title Khatun, see Boyle, 'Khatun', 1933, according to whom it was of Soghdian origin and was borne by wives and female relations of various Turkish Rulers. ..."

- ↑ Fairbank 1978, p. 367

- ↑ Veselin Beševliev, Prabylgarski epigrafski pametnici - 5

- ↑ Moravcsik, G. Byzantinoturcica II. Sprachreste der Türkvölker in den byzantinischen Quellen. Leiden 1983, ISBN 978-90-04-07132-2, с. 156

- ↑ "Oz Beg | Mongolian leader". Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ↑ "MoazzamBegKhans". BeyPeople, every story like you. Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ↑ "About". 2013-08-31. Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ↑ http://www.khyber.org/articles/2007/StudyofthePathanCommunitiesinF.shtml

Sources and references

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Karim, Abdul (2012). "Khan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Etymology OnLine

- RoyalArk- see under each present country

- Princely states in British India – look each up by name, in that section, BUT a taluq in Oudh in that section

- WorldStatesmen- see under each present country