2014–16 Venezuelan protests

| 2014–16 Venezuelan protests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Images from top to bottom and from left to right: Opposition march in Caracas on 12 February 2014, Peaceful march in Maracaibo, Protests at Altamira Square, "Camp Freedom" outside of the UN headquarters in Caracas, March in Caracas following the arrest of Leopoldo Lopez | |||

| Date |

February 12, 2014 – present (2 years, 9 months, 3 weeks and 3 days) | ||

| Location |

| ||

| Status |

Ongoing State of emergency | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

|

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 43 (2014);[8][9] 1 (2015)[10] 9 (2016)[11][12][13][14] | ||

| Injuries | 1032[15]–5285[16][17] | ||

| Arrested | 3400+ (2014);[18] 177 (2015);[19] 600+ (2016)[20][21][14] | ||

In 2014, a series of protests, political demonstrations, and civil insurrection began in Venezuela due to the country's high levels of urban violence, inflation, and chronic shortages of basic goods[22][23] attributed to economic policies such as strict price controls.[24][25] While protests occurred in January 2014, after the murder of actress and former Miss Venezuela Mónica Spear,[26][27] mass protesting began in earnest that February following the attempted rape of a student on a university campus in San Cristóbal. Subsequent arrests of student protestors spurred their expansion to neighboring cities and the involvement of opposition leaders.[28][29] The year's early months were characterized by large demonstrations and violent clashes between protestors and government forces that resulted in over 3,000 arrests and 43 deaths,[8][9][18] including both supporters and opponents of the government.[30] Toward the end of 2014, and into 2015, continued shortages and low oil prices caused renewed protesting.[31] Into 2016, protests occurred following the controversy surrounding the 2015 Venezuelan parliamentary elections as well as the incidents surrounding the 2016 recall referendum. On 1 September 2016, the largest demonstration of the protests occurred, with over 1 million Venezuelans, or over 3% of the entire nation's population, gathered to demand a recall election against President Maduro, with the event being described as the "largest demonstration in the history of Venezuela".[4] Following the suspension of the recall referendum by the government-leaning National Electoral Council (CNE) on 21 October 2016, the opposition organized another protest which was held on 26 October 2016, with over 1.2 million Venezuelans participating.[14]

The majority of protests have been peaceful, consisting of demonstrations, sit-ins, and hunger strikes,[32][33] with an estimated 52% of protests in opposition to the government and smaller numbers in support of various economic and social policy changes.[31] However, small groups of protestors have been responsible for attacks on public property, such as government buildings and public transportation. Erecting improvised street barricades, dubbed guarimbas, has been the most common form of protest, although their use is controversial.[34][35][36][37] Publications like The New York Times have observed that the protests have exposed a class divide in Venezuela, as the protests have primarily occurred in wealthier urban areas with limited participation from the working-class, despite lower-income areas being hit especially hard by the country's economic struggles.[38]

Nicolas Maduro's government characterized the protests as an undemocratic coup d'etat attempt[39] orchestrated by "fascist" opposition leaders and the United States;[40] he blames capitalism and speculation for causing high inflation rates and goods scarcities as part of an "economic war" being waged on his government.[41][42] Although Maduro, a former trade union leader, says he supports peaceful protesting,[43] the Venezuelan government has been widely condemned for its handling of the protests. Venezuelan authorities have reportedly gone beyond the use of rubber pellets and tear gas to instances of live ammunition use and torture of arrested protestors, according to organizations like Amnesty International[44] and Human Rights Watch,[45] while the United Nations[46][47][48] has accused the Venezuelan government of politically-motivated arrests, most notably former Chacao mayor and leader of Popular Will, Leopoldo Lopez, who has used the controversial charges of murder and inciting violence against him to protest the government's "criminalization of dissent."[49][50] Other controversies reported during the protests include media censorship and violence by pro-government militant groups known as colectivos.

Background

Bolivarian Revolution

.jpg)

Venezuela was headed by a series of governments, later labelled as right-wing by the Chávez government, for years. In 1992, Hugo Chávez formed a group named Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200 aiming to take over the government, and attempted a coup d'état.[51][52] Later, another coup was performed while Chávez was in prison. Both coup attempts failed and fighting resulted in around 143–300 deaths.[52] Chávez, after receiving a pardon from president Rafael Caldera, later decided to participate in elections and formed the Movement for the Fifth Republic (MVR) party. He won the Venezuelan presidential election, 1998. The changes started by Chávez were named the Bolivarian Revolution.

Chávez, an anti-American politician who declared himself a democratic socialist, enacted a series of social reforms aimed at improving quality of life. According to the World Bank, Chávez's social measures reduced poverty from about 49% in 1998 to about 25%. From 1999 to 2012, the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), shows that Venezuela achieved the second highest rate of poverty reduction in the region.[53] The World Bank also explained that Venezuela's economy is "extremely vulnerable" to changes in oil prices since in 2012 "96% of the country’s exports and nearly half of its fiscal revenue" relied on oil production. In 1998, a year before Chávez took office, oil was only 77% of Venezuela's exports.[54][55] Under the Chávez government, from 1999 to 2011, monthly inflation rates were high compared to world standards, but were lower than that from 1991 to 1998.[56]

While Chávez was in office, his government was accused of corruption, abuse of the economy for personal gain, propaganda, buying the loyalty of the military, officials involved in drug trade, assisting terrorists such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, intimidation of the media, and human rights abuses of its citizens.[57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66] Government price controls put in place in 2002 which initially aimed for reducing the prices of basic goods have caused economic problems such as inflation and shortages of basic goods.[67] The murder rate under Chávez's administration also quadrupled during his terms in office leaving Venezuela as one of the most violent countries in the world.[68]

On 5 March 2013, Chávez died of cancer and Nicolás Maduro, who was vice president at the time, took Chávez's place.[69] Throughout the year 2013 and into the year 2014, worries about the troubled economy, increasing crime and corruption increased, which led to the start of anti-government protests.

First demonstrations of 2014

Demonstrations against violence in Venezuela began in January 2014,[26] and continued, when former presidential candidate Henrique Capriles shook the hand of President Maduro;[27] this "gesture... cost him support and helped propel" opposition leader Leopoldo López Mendoza to the forefront.[27] According to the Associated Press, well before protests began in the Venezuelan capital city of Caracas, the attempted rape of a young student on a university campus in San Cristóbal, in the western border state of Táchira, led to protests from students "outraged" at "long-standing complaints about deteriorating security under President Nicolas Maduro and his predecessor, the late Hugo Chávez. But what really set them off was the harsh police response to their initial protest, in which several students were detained and allegedly abused, as well as follow-up demonstrations to call for their release". These protests expanded, attracted non-students, and led to more detentions; eventually, other students joined, and the protests spread to Caracas and other cities, with opposition leaders getting involved.[28]

López is a leading figure in the opposition to the government.[70] During events surrounding the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt, Lopez "orchestrated the public protests against Chávez and he played a central role in the citizen's arrest of Chavez's interior minister", Ramón Rodríguez Chacín, though he later tried to distance himself from the event,[71] and did not sign the Carmona Decree.[72] The government of Venezuela banned López from holding elected office; the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that this was illegal, but the Venezuelan government refused to comply with the court ruling.[73]

President Maduro said that San Cristóbal was under siege by right-wing paramilitaries under orders from former Colombian President Alvaro Uribe; Uribe dismissed the allegation as a distraction tactic. Maduro also stated that San Cristobal Mayor Daniel Ceballos, a member of López’s Popular Will Party, would soon join López “behind bars for fomenting violence.” Maduro said: "It's a matter of time until we have him in the same cold cell.”[28] Ceballos was detained in March by the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service without being presented with an arrest warrant[74] and remains in jail.

Corruption

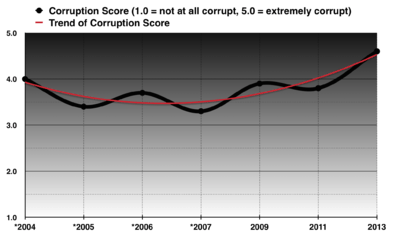

* Score was averaged according to Transparency International's method.

Source: Transparency International

In a 2014 survey by Gallup, nearly 75% of Venezuelans believe corruption is widespread in their government.[75] Leopoldo López has said, "We are fighting a very corrupt authoritarian government that uses all the power, all the money, all the media, all the laws, all the judicial system in order to maintain control."[76]

Corruption in Venezuela is ranked high by world standards. Corruption is difficult to measure reliably, but one well-known measure is the Corruption Perceptions Index, produced annually by a Berlin-based NGO, Transparency International (TNI). Venezuela has been one of the most corrupt countries in TNI surveys since they started in 1995, ranking 38th out of 41 that year[77] and performing very poorly in subsequent years. In 2008, for example, it was 158th out of 180 countries in 2008, the worst in the Americas except Haiti,[78] in 2012, it was one of the 10 most corrupt countries on the index, tying with Burundi, Chad, and Haiti for 165th place out of 176.[79] TNI public opinion data says that most Venezuelans believe the government's effort against corruption is ineffective, that corruption has increased and that government institutions such as the judicial system, parliament, legislature and police are the most corrupt.[80] According to TNI, Venezuela is currently the 18th most corrupt country in the world (160 of 177) and its judicial system has been deemed the most corrupt in the world.[81]

The World Justice Project moreover, ranked Venezuela's government in 99th place worldwide and gave it the worst ranking of any country in Latin America in the 2014 Rule of Law Index.[82] The report says, "Venezuela is the country with the poorest performance of all countries analyzed, showing decreasing trends in the performance of many areas in relation to last year. The country ranks last in the surrender of accounts by the government due to an increasing concentration of executive power and a weakened checks and balances." The report further states that "administrative bodies suffer inefficiencies and lack of transparency…and the judicial system, although relatively accessible, lost positions due to increasing political interference. Another area of concern is the increase in crime and violence, and violations of fundamental rights, particularly the right to freedom of opinion and expression."[65]

Economic problems

According to the 2013 Global Misery Index Scores, Venezuela was ranked as the top spot globally with the highest misery index score.[83] In data provided by the CIA, Venezuela had the second highest inflation rate (56.20%) in the world for 2013, only behind the war-torn Syria.[84] The money supply of the Bolivar Fuerte in Venezuela also continues to accelerate, possibly helping to fuel more inflation.[85] The Venezuelan government's economic policies, including strict price controls, led to one of the highest inflation rates in the world with "sporadic hyperinflation",[67] and have caused severe shortages of food and other basic goods.[25] The Heritage Foundation, a US-based conservative advocacy group, ranked Venezuela at 175 of 178 in economic freedom and was classified as a "Repressed" economy in its 2014 Index of Economic Freedom report.[86] According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), activity in Venezuela is uncertain but may continue to slow for the year 2014 saying that "loose macroeconomic policies have generated high inflation and a drain on official foreign exchange reserves". Venezuela was also the only country in the world that the International Monetary Fund predicted that their GDP will contract.[87] Data provided by economist Steve H. Hanke of the Cato Institute shows that Venezuela's current economy, as of March 2014, had an implied inflation rate hovering above 300%, an official inflation rate around 60% and a product scarcity index rising above 25% of goods.[88] Hanke believes that "State-controlled prices - prices that are set below market-clearing price - always result in shortages" and that "The shortage problem will only get worse, as it did over the years in the Soviet Union".[89] More than half of those interviewed in a Datos survey held the Maduro government responsible for the country's current economic situation and most thought the country’s economic situation would be worse or just as bad in the next 6 months of 2014.[90][91] President Maduro has blamed the economic troubles on an alleged "economic war" being waged against his government; specifically, he has placed blame on capitalism and speculation.[42]

Price controls created by the Venezuelan government had hurt businesses and led to shortages, long queues, and looting.[92] In 2013, as the country suffered from shortages of necessities such as toilet paper, milk, and flour, Venezuela devalued its currency[93][94] The government's catastrophic monetary policy means that businesses cannot afford to import basic goods such as paper;[95] the National Guard occupied MANPA, the nation's largest manufacturer of toilet paper, with the aim to check operations for "possible diversion of distribution" and "illegal management".[96] In early 2014, however, members of Popular Will who were visiting El Salvador claimed that Venezuelan toilet paper, along with other Venezuelan products, had been given to El Salvador by the Venezuelan government, even though such items were not available in Venezuela unless one waited in “humiliating lines for hours.” Among the items they found on sale in El Salvador, and displayed at a press conference, were Alba brand rice and beans. Abelardo Diaz said that the alliances that result in these subsidized Venezuelan goods being shipped abroad at the expense of Venezuelan citizens “are not productive for our people”. Díaz called it “treason” to support such arrangements, which had led to so much injury and death on the part of protesters.[97] President of the National Statistics Institute (INE) Elias Eljuri suggested that all shortages in the country were due to Venezuelan's eating, saying that “95% of people eat three or more meals a day” while referencing a national survey.[98][99] However, data provided by INE showed that in 2013, food consumption by Venezuelans actually decreased.[100]

An article by The Guardian noted that a "significant proportion" of the subsidized basic goods in short supply were being smuggled into Colombia and sold for far higher prices,[40] with the Venezuelan government claiming that as much as 40% of the basic commodities it subsidizes for the domestic market are being smuggled out of the country.[101] However, economists disagree with the Venezuelan government's claim stating that only 10% of subsidized products are smuggled out of the country.[102]

An Associated Press report in February 2014 noted that “legions of the sick across the country” were being “neglected by a health care system doctors say is collapsing after years of deterioration.” Doctors at one hospital “sent home 300 cancer patients last month when supply shortages and overtaxed equipment made it impossible for them to perform non-emergency surgeries.” The government, which controlled “the dollars needed to buy medical supplies,” had “simply not made enough” dollars available for those supplies, the AP reported. As a result, “many patients began dying from easily treatable illnesses when Venezuela's downward economic slide accelerated after Chavez's death.” Doctors called it impossible “to know how many have died, and the government doesn't keep such numbers, just as it hasn't published health statistics since 2010.” Among the items “in critically short supply” were “needles, syringes and paraffin used in biopsies to diagnose cancer; drugs to treat it; operating room equipment; X-ray film and imaging paper; blood and the reagents needed so it can be used for transfusions.” The previous month, the government had “suspended organ donations and transplants.” Also, over “70 percent of radiotherapy machines” were “now inoperable.” Dr. Douglas Natera, president of the Venezuelan Medical Federation, said, "Two months ago we asked the government to declare an emergency,” but they received no response. Health Minister Isabel Iturria refused to give the AP an interview, while a deputy health minister, Nimeny Gutierrez, “denied on state TV that the system is in crisis.”[103]

Violent crime

In Venezuela, a person is murdered every 21 minutes.[104][105] In the first two months of 2014, nearly 3,000 people were murdered – 10% more than in the previous year and 500% higher than when Hugo Chávez first took office.[106] In 2014, Quartz claimed that the high murder rate was due to Venezuela’s “ growing poverty rate; rampant corruption; high levels of gun ownership; and a failure to punish murderers (91% of the murders go unpunished, according to the Institute for Research on Coexistence and Citizen Security).”[106] InsightCrime attributed the escalating violence to "high levels of corruption, a lack of investment in the police force and weak gun control."[26]

Following the January killing of actress and former Miss Venezuela Mónica Spear and her ex-husband in a roadside robbery in the presence of their five-year-old daughter, who herself was shot in the leg,[26] Venezuela was described by Channel 4 as “one of the most dangerous countries in the world,” [26] a country “where crime escalated during the administration of former President Hugo Chávez and killings are common in armed robberies.”[26] The Venezuelan Violence Observatory said in March 2014 the country's murder rate was now nearly 80 deaths per 100,000 people, while government statistics put it at 39 deaths per 100,000.[107] The number of those murdered during the previous decade was comparable to the death rate in Iraq during the Iraq War; during some periods, Venezuela had a higher rate of civilian deaths than Iraq, even though the country was at peace.[108] Crime had also affected the economy, according to Jorge Roig, president of the Venezuelan Federation of Chambers of Commerce, who said that many foreign business executives were too scared to travel to Venezuela and that many owners of Venezuelan companies live abroad, with the companies producing less as a result.[109]

The opposition says that crime is the government's fault "for being soft on crime, for politicizing and corrupting institutions such as the judiciary, and for glorifying violence in public discourse," while the government says that "capitalist evils" are to blame, such as drug trafficking and violence in the media.[110]

The United States State Department and the Government of Canada have warned foreign visitors that they may be subjected to robbery, kidnapping for a ransom, or sale to terrorist organizations and murder.[111][112] The United Kingdom's Foreign and Commonwealth Office has advised against all travel within 80 km (50 miles) of the Colombian border in the states of Zulia, Táchira, and Apure.[113]

Elections

On 14 April 2013, Nicolas Maduro won the presidential election with 50.6% of the vote, ahead of the 49.1% of candidate Henrique Capriles Radonski. The results were surprisingly close[114] because Hugo Chávez had defeated Capriles less than a year before by a margin of more than 10 points,[115] and Maduro had led most polls through the campaigns by large margins.[116][117][118][119][120] Opposition leaders made accusations of fraud shortly after the election.[121] Capriles refused to accept the results, alleging that voters had been coerced to vote for Maduro and claiming election irregularities. The National Electoral Council (CNE), which conducted a post-election audit of a random selection of 54% of the votes, comparing electronic records with paper ballots, claimed to find nothing suspicious.[122][123] Capriles initially called for an audit of the remaining 46% of the votes, asserting that this would show that he had won the election. The CNE agreed to carry out an audit, and planned to do so in May.[122][123] Later Capriles changed his mind, adding demands for a full audit of the electoral registry, and calling the audit process “a joke”.[122]

Before the government agreed to a full audit of the vote, there were public protests by opponents of Maduro. The crowds were ultimately dispersed by National Guard members using tear gas and rubber bullets.[124] President Maduro responded to the protests by saying, “If you want to try to oust us through a coup, the people and the armed forces will be waiting for you.” [125] The clashes resulted in 7 people killed and dozens injured. President Maduro described the protests as a "coup" attempt, and blamed the United States for them. Finally, Capriles told protesters to stop and not play the "government's game," so there would be no more deaths.[126]

On 12 June 2013 the results of the partial audit were announced. The CNE certified the initial results and confirmed Maduro's electoral victory.[127] The Carter Center, founded by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, stated in a detailed report on the elections that “the extremely close election results…presented an electoral and political conflict not seen since the 2004 recall referendum. Accompanied by divisive public discourse on all sides, the electoral dispute interrupted not only an incipient national consensus on the reliability of the electoral outcome, but also the ability to move forward with constructive debate and dialogue on other issues of import to the country.” The Carter Center noted the lack of “agreement…about the quality of the voting conditions and whether every registered voter is able to vote one time, and only one time,” and the fact that “inequities in campaign conditions in terms of both access to financial resources and access to the media diminish the competitiveness of elections, particularly in a legal framework that permits indefinite reelection of public officials.” The Carter Center issued a 9-point set of recommendations to make Venezuelan elections fairer and the results more reliable.[128] Government resources were used to support the ruling party's electoral campaigns, and government vehicles were used for transport. During the local election campaign, Maduro spent two hours per day on live television,.[129]

The opposition's defeat in the December 8 municipal elections,[130] which it had framed as a 'plebiscite' on Maduro's presidency,[131] ignited an internal debate over strategy. Moderate opposition leaders Henrique Capriles and Henri Falcón argued for 'unity' and dialogue with the government, and attended meetings held by the President to discuss cooperation among the country's mayors and governors.[132][133][134] Other opposition leaders, such as Leopoldo López and Marina Corina Machado, opposed dialogue[135] and called for a new strategy to force an immediate change in the government.[136][137]

Protest violence

"Colectivos"

Militant groups known as "colectivos" attacked protesters and opposition TV staff, sent death threats to journalists, and tear-gassed the Vatican envoy after Hugo Chávez accused these groups of intervening with his government. Colectivos helped assist the government during the protests.[138] Human Rights Watch said that "the government of Venezuela has tolerated and promoted groups of armed civilians," which HRW claims have "intimidated protesters and initiated violent incidents".[139] Socialist International also condemned the impunity that irregular groups have had while attacking protesters.[140] President Maduro has thanked certain groups of motorcyclists for their help against what he views as a "fascist coup d'etat... being waged by the extreme right", but also distanced himself from armed groups, stating that they "had no place in the revolution".[141] On a later occasion, President Maduro issued a condemnation of all violent groups and said a government supporter would go to jail if he performed a crime, just as an opposition supporter would. He said that someone who is violent has no place as a government supporter and thus should leave the pro-government movement immediately.[142]

Some "colectivos" have acted violently against the opposition without impediment from Venezuelan government forces.[143] Colectivos in several trucks allegedly attacked an apartment complex known for protesting damaging 5 vehicles, leaving 2 burnt, and fired several shots into the apartments leaving one person injured from a gunshot wound.[144] According to a correspondent from Televen, armed groups attempted to kidnap and rape individuals in an apartment complex in Maracaibo without intervention from the National Guard.[145][146][147][148] Vice President of Venezuela, Jorge Arreaza, praised colectivos saying, "If there has been exemplary behavior it has been the behavior of the motorcycle colectivos that are with the Bolivarian revolution."[149] However, on March 28, Arreaza promised that the government would disarm all irregular armed groups in Veneuela.[150] Colectivos have also been called a "fundamental pillar in the defense of the homeland" by the Venezuelan Prison Minister, Iris Varela.[151][152]

In the month of March in 2014, paramilitary groups acted violently in 437 protests, about 31% of total protests in March, where gunshot wounds were reported in most protests they were involved in.[16] Armed colectivos allegedly attacked and burnt down Universidad Fermín Toro after intimidating student protesters and shooting one.[153][154]

Human Rights Watch reported that government forces "repeatedly allowed" colectivos "to attack protesters, journalists, students, or people they believed to be opponents of the government with security forces just meters away" and that "in some cases, the security forces openly collaborated with the pro-government attackers". Human Rights Watch also stated that they "found compelling evidence of uniformed security forces and pro-government gangs attacking protesters side by side. One report said that government forces aided pro-government civilians that shot protesters with live ammunition.[45]

These groups of guarimberos, fascists and violent [people], and today now other sectors of the country’s population as well have gone out on the streets, I call on the UBCh, on the communal councils, on communities, on colectivos: flame that is lit, flame that is extinguished.

President Nicolas Maduro [45]

Human Rights Watch stated that "Despite credible evidence of crimes carried out by these armed pro-government gangs, high-ranking officials called directly on groups to confront protesters through speeches, interviews, and tweets." According to Human Rights Watch, President Nicolas Maduro "on multiple occasions called on civilian groups loyal to the government to 'extinguish the flame' of what he characterized as 'fascist' protesters".[45] The governor of the state of Carabobo, Francisco Ameliach, called on Units of Battle Hugo Chávez (UBCh), a government created civilian group that according to the government is a “tool of the people to defend its conquests, to continue fighting for the expansion of the Venezuelan Revolution”. In a tweet, Ameliach asked UBCh to launch a rapid counterattack against protesters saying, "Gringos (Americans) and fascists beware" and that the order would come from the President of the National Assembly, Diosdado Cabello.[45][155][156][157]

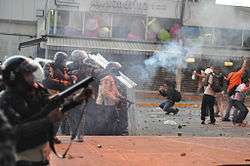

Government forces

Government authorities have used "unlawful force against unarmed protesters and other people in the vicinity of demonstrations". Government agencies involved in the use of unlawful force include the National Guard, the National Police, the Guard of the People, and other government agencies. Some common abuses included "severely beating unarmed individuals, firing live ammunition, rubber bullets, and teargas canisters indiscriminately into crowds, and firing rubber bullets deliberately, at point-blank range, at unarmed individuals, including, in some cases, individuals already in custody". Human Rights Watch said that "Venezuelan security forces repeatedly resorted to force—including lethal force—in situations in which it was wholly unjustified" and that "the use of force occurred in the context of protests that were peaceful, according to victims, eyewitnesses, lawyers, and journalists, who in many instances shared video footage and photographs corroborating their accounts".[45]

Use of firearms by state authorities

Government forces have used firearms to control protests.[159] Amnesty International reported that they had "received reports of the use of pellet guns and tear gas shot directly at protesters at short range and without warning" and that "Such practices violate international standards and have resulted in the death of at least one protester." They also said that "Demonstrators detained by government forces at times have been denied medical care and access to lawyers". Amnesty International was also worried about "the use of chemical toxins in high concentrations” by government forces and recommended better training for them.[44] During the months of protest, the heavy use of tear gas by authorities in Chacao affected surrounding residents and forced them to wear gas masks to "survive" in their homes.[160] Some violent demonstrations have been controlled with tear gas and water cannons.[161]

The New York Times reported that a protester was "shot at such close range by a soldier at a protest that his surgeon said he had to remove pieces of the plastic shotgun shell buried in his leg, along with the shards of keys" that were in their pocket at the time. Venezuelan authorities have also been accused of shooting shotguns with "hard plastic buckshot at point-blank range" which allegedly injured a great number of protesters and killed a woman. The woman who was killed was banging a pot outside of her house in protest when her father reported that "soldiers rode up on motorcycles" and that the woman then fell while trying to seek shelter in her home. Witnesses of the incident then said that "a soldier got off his motorcycle, pointed his shotgun at her head and fired". The shot that was fired by the policeman "slammed through her eye socket into her brain". The woman died days before her birthday. Her father said that the soldier who killed her was not arrested.[162] There has also been claims by the Venezuelan Penal Forum accusing authorities that have allegedly attempted to tamper with evidence, covering up that they had shot students.[163]

El Nacional claimed that the objective of those attacking opposition protesters is to kill since many of the protesters that were killed were shot in vulnerable areas like the head and that, "9 of the 15 dead people were from the 12F demonstrators, who were injured by state security forces or paramilitaries linked to the ruling party."[164] El Universal has claimed that Melvin Collazos of SEBIN, and Jonathan Rodríquez, a bodyguard of the Minister of the Interior and Justice Miguel Rodríguez Torres, are in custody after shooting unarmed, fleeing, protesters several times in violation of protocol.[165] The article 68 of the Venezuelan Constitution states that "the use of firearms and toxic substances to control peaceful demonstrations is prohibited", and that "the law shall regulate the actions of the police and security control of public order."[166][167]

Abuse of protesters and detainees

According to Amnesty International, "torture is commonplace" against protesters by Venezuelan authorities despite Article 46 of the Venezuelan Constitution prohibiting "punishment, torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment".[168] During the protests, there were hundreds of reported cases of torture.[169] In a report titled Punished for Protesting following a March investigation of conduct during the protests, Human Rights Watch said that those who were detained by government authorities were subjected to "severe physical abuse" with some abuses including being beaten "with fists, helmets, and firearms; electric shocks or burns; being forced to squat or kneel, without moving, for hours at a time; being handcuffed to other detainees, sometimes in pairs and others in human chains of dozens of people, for hours at a time; and extended periods of extreme cold or heat." It was also reported that "many victims and family members we spoke with said they believed they might face reprisals if they reported abuses by police, guardsmen, or armed pro-government gangs".[45]

Amnesty International "received reports from detainees who were forced to spend hours on their knees or feet in detention centers". Amnesty International also reported that a student was forced at gunpoint by plainclothes officers to sign a confession to acts he did not commit where his mother explained that “They told him that they would kill him if he didn’t sign it, ... He started to cry, but he wouldn’t sign it. They then wrapped him in foam sheets and started to hit him with rods and a fire extinguisher. Later, they doused him with gasoline, stating that they would then have evidence to charge him.” Amnesty International said that the Human Rights Center at the Andres Bello Catholic University had reported that, “There are two cases that involved electric shocks, two cases that involved pepper gas and another two cases where they were doused with gasoline,” she said. “We’ve found there to be systematic conduct on the part of the state to inflict inhumane treatment on detainees because of similar reports from different days and detention centers.”[44]

The New York Times reported that the Penal Forum said that abuses are "continuous and systematic" and that Venezuelan authorities were "widely accused of beating detainees, often severely, with many people saying the security forces then robbed them, stealing cellphones, money and jewelry". In one case, a group of men said that when they were leaving a protest since it turned violent, "soldiers surrounded the car, broke the windows and tossed a tear gas canister inside". A man then said that a soldier "fired a shotgun at him at close range" while in the vehicle. The men were then "pulled from the car and beaten viciously" then one soldier "smashed their hands with the butt of his shotgun, telling them it was punishment for protesters’ throwing rocks." The vehicle was then set on fire. One protester said that while detained, soldiers "kicked him over and over again." The protesters he was with "were handcuffed together, threatened with an attack dog, made to crouch for long periods, pepper sprayed and beaten." The protester then said that he was "hit so hard on the head with a soldier’s helmet that he heard it crack". A woman also said she was with her daughter when "they were swept up by National Guard soldiers, taken with six other women to a military post and handed over to female soldiers". The women then said that "soldiers beat them, kicked them and threatened to kill them". The women also said that soldiers threatened to rape them, cut their hair and "were released only after being made to sign a paper stating that they had not been mistreated."[162]

Human Rights Watch reported that a man was going home and was attacked by National Guardsman dispersing a group of protesters. He was then hit by rubber bullets the National Guardsmen shot, beat by the National Guardsmen, and then shot in the groin. Another man was detained, shot repeatedly with rubber bullets, beat with rifles and helmets by three National Guardsman and was asked "Who's your president?" Some individuals that were arrested innocently were beaten and forced to repeat that Nicolas Maduro was president.[45]

NTN24 reported from a lawyer that National Guardsmen and individuals with "Cuban accents" in Mérida forced three arrested adolescents to confess to crimes they did not commit and then the adolescents "kneeled and were forced to raise their arms then shot with buckshot throughout their body" during an alleged "target practice".[170][171] NTN24 reported that some protesters were allegedly tortured and raped by government forces who detained them during the protests.[172] El Nuevo Herald reported that student protesters had been tortured by government forces in an attempt for the government to make them admit they are part of a plan of foreign individuals to overthrow the Venezuelan government.[173] In Valencia, protesters were dispersed by the National Guard in El Trigál where four students (three men and one woman) were attacked inside of a car while trying to leave the perimeter;[174] the three men were imprisoned and one of them was allegedly sodomized by one of the officers with a rifle.[175]

In an El Nacional article sharing interviews with protesters who were arrested, individuals explained their experiences in jail. One protester explained how he was placed into a 3 by 2 meter cell with 30 other prisoners where the inmates had to defecate in a bag behind a single curtain. The protester continued explaining how prisoners dealt punishments toward one another and the punishment for "guarimberos" was to be tied and gagged, which would allegedly occur without intervention from the authorities. Other arrested protesters interviewed also explained their fears of being imprisoned with violent criminals.[176]

The director of the Venezuelan Penal Forum, Alfredo Romero, called for both the opposition and the Venezuelan government to listen to the claims of the alleged human rights violations that have not been heard. He also reported that a woman was tortured with electric shocks to her breasts.[177][178] The Venezuelan Penal Forum also reported students being tortured with electric shocks, being beaten, and being threatened of being set on fire after they were doused in gasoline after they were arrested.[179]

Human Rights Watch reported that, "not all of the security force members or justice officials encountered by the victims in these cases participated in the abusive practices. Indeed, in some of the cases ... security officials and doctors in public hospitals had surreptitiously intervened to help them or to ease their suffering". Some National Guardsman assisted detainees that were being held in "incommunicado". It was also reported that "[i]n several cases, doctors and nurses in public hospitals—and even those serving in military clinics—stood up to armed security forces, who wanted to deny medical care to seriously wounded detainees. They insisted detainees receive urgent medical care, in spite of direct threats—interventions that may have saved victims’ lives".[45]

Government's response to abuses

The Venezuelan Attorney General's office reported it was conducting, as of the Human Rights Watch report, 145 investigations into alleged human rights abuses, and that 17 security officials had been detained in connection to them. President Maduro and other government officials have acknowledged human rights abuses, but said they were isolated incidents and not part of a larger pattern.[45] When opposition parties asked for a debate about torture in the National Assembly, the Venezuelan government refused, blaming the violence on the opposition saying, "The violent are not us, the violent are in a group of opposition".[180]

El Universal stated that Melvin Collazos of SEBIN, and Jonathan Rodríquez a bodyguard of the Minister of the Interior and Justice Miguel Rodríguez Torres, were in custody after shooting unarmed, fleeing, protesters several times in violation of protocol.[165] President Maduro announced that the personnel who fired at protesters were arrested for their actions.[181]

Innocent individuals arrested

According to Human Rights Watch, Venezuelan government authorities arrested many innocent people. They stated that "the government routinely failed to present credible evidence that these protesters were committing crimes at the time they were arrested, which is a requirement under Venezuelan law when detaining someone without an arrest warrant". They also explained that "Some of the people detained, moreover, were simply in the vicinity of protests but not participating in them. This group of detainees included people who were passing through areas where protests were taking place, or were in public places nearby. Others were detained on private property such as apartment buildings. In every case in which individuals were detained on private property, security forces entered buildings without search orders, often forcing their way in by breaking down doors." One man was in his apartment when government forces fired tear gas into the building. The man went to the courtyard for fresh air and was arrested for no reason after police broke into the apartments.[45]

Violent protests

Apart from peaceful demonstrations, an element in some protests includes burning trash, creating barricades and have resulted in violent clashes between the opposition and state authorities. Human Rights Watch said that protesters "who committed acts of violence at protests were a very small minority—usually less than a dozen people out of scores or hundreds of people present". It was reported that barricades were the most common form of protest and that occasional attacks on authorities with Molotov cocktails, rocks and slingshots occurred. In rare instances, homemade mortars were used by protesters. The use of Molotov Cocktails in some cases caught authorities and some government vehicles on fire.[45] President Maduro has stated that some protests "have included arson attacks on government buildings, universities and bus stations."[182]

The National Guard alleged that they had prevented some violent students from the University of the Andes (ULA) from entering a premises.[183] The governor of Aragua state, Tarek El Aissami, claimed that six opposition protesters were arrested for having firearms with one of the arrested being accused of allegedly shooting an officer with El Aissami saying, "He's a fascist. We ordered the Public Ministry and the entire judiciary application of all penalties"[184] The article 68 of the constitution also states that "citizens have the right to demonstrate" as long as it is "peacefully and without weapons".[166][167]

Barricades

Throughout the protests, a common tactic that has divided opinions among Venezuelans and the anti-government opposition has been erecting burning street barricades, colloquially known as guarimbas. Street barricades, which stop vehicles from passing, violate the 50th article of the constitution of Venezuela, which grants the right of free transit.[185][186] Initially, these barricades consisted of piles of trash and cardboard set on fire at night, and were easily removed by Venezuelan security forces. Guarimbas have since evolved into "fortress-like structures" of bricks, mattresses, wooden planks and barbed wire guarded by protestors, who "have to resort to guerrilla-style tactics to get a response from the government of President Nicolas Maduro". However, their use is controversial. Critics claim guarimbas, which are primarily erected in residential areas, victimize local residents and businesses and have little political impact.[34]

President Maduro and poor sectors in some cities criticized barricades, with Maduro denouncing that “thousands of people are affected by a small group of ten or twenty persons”, and that “some of them don’t have access to health care, including children and elders”,[187] although many opposition protesters argue that guarimbas are also used as a protection against armed groups, and not only as a form of protest.[188] At some barricades, "guayas" or wires are placed near them. These wires are difficult for motorists to see and have reportedly killed a man on a motorcycle. Those who were protesting at the barricades claimed that the guayas were used for defense against Tupamaros and colectivos groups that had been allegedly "instilling terror" among the protesters. However, the government alleges that the guayas are placed groups of "fascists" saying that have "the sole intention of destabilizing".[189] Contested statements claim that at least thirteen deaths had been attributed to opposition supporters at these barricades.[40] It has also been reported that protesters have used homemade caltrops made of hose pieces and nails, colloquially known in Spanish as “miguelitos” or "chinas", to deflate motorbike tires.[190][191] The government has also condemned their usage.[192][193] Some protestors have cited videos of protests in Ukraine and Egypt as inspiration for their tactics in defending barricades and repelling government forces, such as using common items such as beer bottles, metal tubing, and gasoline to construct fire bombs and mortars, while using bottles filled with paint to block the views of tank and armored riot vehicle drivers. Common protective gear for protestors include motorcycle helmets, construction dust masks, and gloves.[194] President Maduro claimed that barricades had resulted in more than 50 deaths.[195]

Attacks on public property

Public property has been a frequent target of protestor violence. Attacks have been reported by Attorney General Luisa Ortega Diaz on the Ministerio Publico's headquarters;[196] by Minister for Science, Technology and Innovation Manuel Fernandez on the headquarters of the nationalized telephone service CANTV in Barquisimeto;[197][198] and by Mayor Ramón Muchacho on the Bank of Venezuela and BBVA Provincial.[199] Many government officials have used social media to announce attacks and document damage. Carabobo state governor Francisco Ameliach used Twitter to report attacks by the "fascist right" on the United Socialist Party of Venezuela's headquarters in Valencia,[200] as did José David Cabello after an attack by "armed opposition" on the headquarters of the National Integrated Service for the Administration of Customs Duties and Taxes.[201] First Lady of Venezuela Vielma Karla Jimenez said the headquarters of the Fundacion de la Familia Tachirense had been attacked by "hooligans" and posted photographs of the damage on her Facebook page.[202]

In some attacks, institutions have suffered severe damage. In anger over Maria Corina Machado being teargassed for trying to enter the National Assembly after having been expelled, some protestors attacked the headquarters of the Ministry of Public Works & Housing. President Maduro said the attack forced the evacuation of workers and about 89 children from the building after it had become "engulfed in flames" with much of the building's equipment destroyed and its windows shattered.[203][204] Two weeks earlier, the Tachira state campus of the National Experimental University of the Armed Forces, a military university that was converted by government decree to a public university, was attacked with petrol bombs and largely destroyed. The dean, who blamed far-right groups, highlighted damage to the university's library, technology labs, offices, and buses.[205][206] A National Guard officer stationed at the university was shot dead days later during a second attack on the campus.[206]

Many vehicles have been destroyed, including those belonging to the national food distribution companies PDVAL[207] and Bicentenario.[208] Electricity Minister Jesse Chacon said 22 vehicles of the company Corpoelec had been burned and that some public property electricity distribution wires were cut down, the result of alleged "fascist vandalism."[209] The Land Transport Minister, Haiman El Troudi, reported attacks on the transport system.[210] President Maduro showed a video of "fascist groups" damaging transportation vehicles and reported that 50 damaged units will have to be replaced.[211] Vehicles affected by the attacks on land transportation belong to various organizations and bus lines including BusCaracas, BusGuarenas-Guatire, Metrobus[212][213][214] and the Caracas subway, with the consequence of the temporary closure of some transport routes and the closing down of stations of the Caracas subway to prevent damage.[215]

Timeline of events

According to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict (OVCS), 9,286 protests occurred in 2014, the greatest number of protests occurring in Venezuela in decades.[31] The majority of protests, 6,369 demonstrations, occurred during the first six months of 2014 with an average of 35 protests per day.[32] SVCO estimated that 445 protests occurred in January; 2,248 in February; 1,423 in March; 1,131 in April; 633 in May; and 489 in June.[32] The main reason of protest was against President Maduro and the Venezuelan government with 52% of demonstrations and the remaining 42% of protests were due to other difficulties such as labor, utilities, insecurity, education and shortages.[31] Most protesting began in the first week of February, reaching peak numbers in the middle of that month following the call of students and opposition leaders to protest.[32]

The number of protests then declined into mid-2014 only to increase slightly in late 2014 into 2015 following the drop in the price of oil and due to the shortages in Venezuela; with protests denouncing shortages increasing nearly fourfold, from 41 demonstrations in July 2014 to 147 in January 2015.[31] In January 2015, there were 518 protests compared to the 445 in January 2014, with the majority of these protests involving shortages in the country.[216] In the first half of 2015, there were 2,836 protests, with the number of protests dropping from 6,369 in the first half of 2014.[217] Of the 2,836 protests that occurred in the first half of 2015, a little more than 1 of 6 events were demonstrations against shortages.[217] The drop in numbers participating in protests was attributed by analysts to the fear of a government crackdown and Venezuelans being preoccupied with trying to find food due to the shortages.[218]

In the first two months of 2016, over 1,000 protests occurred along with dozens of lootings, with the SVCO stating that the number of protests were increasing throughout Venezuela.[219] From January to October 2016, 5,772 protests occurred throughout Venezuela with protests for political rights increasing in late-2016.[220]

Domestic reactions

Government

Government allegations

In March 2014, the Venezuelan government suggested that the protesters wanted to repeat the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt.[221] President Maduro also calls the opposition "fascists".[222]

President Maduro has said: "Beginning February 12, we have entered a new period in which the extreme right, unable to win democratically, seeks to win by fear, violence, subterfuge and media manipulation. They are more confident because the US government has always supported them despite their violence."[223] The Venezuelan government claimed that the United States government is actively supporting the opposition and has been accused of meddling with Venezuelan affairs by trying to destabilize President Maduro through its "soft coup" tactic.[224] In an op-ed in The New York Times, President Maduro said that the protesters actions had caused several millions of dollars' worth of damage to public property. He continued, saying that the protesters have an undemocratic agenda to overthrow a democratically elected government, and that they are supported by the wealthy while receiving no support from the poor. He also added that crimes by government supporters will never be tolerated and that all perpetrators, no matter who they support, will be held accountable for their actions, and that the government has opened a Human Rights Council to investigate any issues, as "every victim deserves justice".[41] In an interview with The Guardian, President Maduro pointed to the United States' history of backing coups, citing examples such as the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état, 1973 Chilean coup d'état, and 2004 Haitian coup d'état.[40] President Maduro also highlighted whistleblower Edward Snowden's revelations, U.S. state department documents, and 2006 WikiLeaks cables from the U.S.'s ambassador to Venezuela outlining plans to "'divide', 'isolate' and 'penetrate' the Chávez government" and revealing opposition group funding, some through USAid (which, according to an AP investigation,[225] supposedly funded attempts to create political unrest and rioting in Cuba through social media) and the Office of Transition Initiatives, including $5 million earmarked for overt support of opposition political groups in 2014.[40] The United States has denied all involvement in the Venezuelan protests with President Barack Obama saying, "Rather than trying to distract from protests by making false accusations against U.S. diplomats, Venezuela's government should address the people's legitimate grievances".[226][227] USAID had also denied the alleged attempts of causing unrest in Cuba saying "the program was similar to others that the agency has financed in Africa, Asia and Latin America" and that the "programs are part of our mission to promote open communications”.[225]

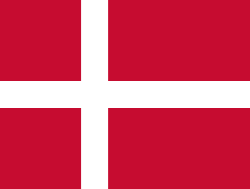

President Maduro also claimed that the government of Panama was interfering with the Venezuelan government.[228] At the same time the Venezuelan government supporters commemorated the first year since the death of President Chávez, the Venezuelan government severed diplomatic relations with Panama. Three days following, the government declared cessation of economic ties with Panama.

During a news conference on 21 February, Maduro once again accused the United States and NATO of trying to overthrow his government through media and claimed that Elias Jaua will be able to prove it.[229] President Maduro asked United States president Barack Obama for help with negotiations.[230] On 22 February during a public speech at the Miraflores Palace, President Maduro spoke out against the media, international artists, and criticized the President of the United States saying, "I invoke Obama and his African American spirit, to give the order to respect Venezuela."[231] On 26 February, President Maduro criticized the international artists and celebrities again saying, "They think because they are famous and we like their songs, they can determine what to do with the country, they were wrong about Venezuela, Venezuela is to be respected."[232]

During a press conference on 18 March, President of the National Assembly Diosdado Cabello said that the government accused María Corina Machado of 29 counts of murder due to the deaths resulting from the protests.[233] María Corina Machado was briefly detained when she arrived at Maiquetia Airport on 22 March and was later released that day.[234]

On 3 April, President Maduro denounced a "secessionist" plan against Venezuela planned by the opposition. He declared that the Táchira, Mérida, Carabobo, Lara, Nueva Esparta and Zulia states would be part of the secessionist plan, that its objective was to divide the nation and that the states that accomplished it would be autonomous or would merge with the Republic of Colombia.[235][236][237][238][239][240][241]

On 3 June, President Maduro claimed on his radio talk show that the United States and the Venezuelan opposition had plans to assassinate him saying Maria Corina Machado was involved in the plans, called her a "killer", and said that there was evidence from emails that he "did not want to publicly display".[242]

The New York Times editorial board stated that such fears of a coup by President Maduro "appear to be a diversion strategy by a maniacal statesman who is unable to deal with the dismal state of his country’s economy and the rapidly deteriorating quality of life despite having the world’s largest oil reserves".[243] The allegations made by the government were called by David Smilde of the Washington Office on Latin America as a form of unity, with Smilde saying, "When you talk about conspiracies, it's basically a way of rallying the troops. It's a way of saying 'this is no time for dissent'".[244]

Arrests

On 15 February, the father of Leopoldo Lopez said "They are looking for Leopoldo, my son, but in a very civilized way" after his house was searched through by the government.[245] The next day, Popular Will leader Leopoldo Lopez announced that he would turn himself in to the Venezuelan government after one more protest saying, "I haven't committed any crime. If there is a decision to legally throw me in jail I'll submit myself to this persecution."[246] On 17 February, armed government intelligence personnel illegally forced their way into the headquarters of Popular Will in Caracas and held individuals that were inside at gunpoint.[247] On 18 February, Lopez explained during his speech how he could have left the country, but "stayed to fight for the oppressed people in Venezuela".[248] Lopez surrendered to police after giving his speech and was transferred to the Palacio de Justicia in Caracas where his hearing was postponed until the next day.[249]

Human Rights Watch demanded the immediate release of Leopoldo Lopez after his arrest saying, "The arrest of Leopoldo López is an atrocious violation of one of the most basic principles of due process: you cannot imprison someone without evidence linking him with a crime".[250][251]

During the last few weeks of March, the government began making more accusations and arresting opposition leaders. Opposition mayor Vicencio Scarano Spisso was tried and sentenced to ten and a half months of jail for failing to comply with a court order to take down barricades in his municipality which resulted in various deaths and injuries in the previous days.[252] Adán Chávez, older brother of Hugo Chávez, joined the government's effort of criticizing opposition mayors who have supported the protest actions, stating that they "could end up like Scarano and Ceballos" by being charged for various cases.[253] On 27 February, the government issued an arrest warrant for Carlos Vecchio, a leader of Popular Will on various charges.[254]

On 25 March, President Maduro announced that three Venezuelan Air Force generals were arrested for allegedly planning a "coup" against the government and in support for the protests and will be charged accordingly.[255] On April 29, Captain Juan Carlos Caguaripano Scott of the Bolivarian National Guard criticized the Venezuelan government in a YouTube video. He said that "As a national guard member who loves this country and is worried about our future and our children". He continued saying that, “There are sufficient reasons to demand the resignation of the president, to free the political prisoners” and said that the government conducted a "fratricidal war". This video was posted days after Scott was accused of plotting a coup against the government "joining three generals from the air force and another captain of the national guard already accused of plotting against the state".[256]

225 Venezuelan military officers rejected the allegations against the three air force generals stating that to bring them before a military court "would be violating their constitutional rights, as it is essential first to submit a preliminary hearing" and asked the National Guard "to be limited to fulfill its functions under articles 320, 328 and 329 of the Constitution and cease their illegal activities repression of public order".[257] The allegations against the air force generals were also seen by former Venezuelan officials and commanders as a "media maneuver" to gain support from UNASUR since President Maduro timed it for the meeting and was not able to give details.[258]

Law enforcement actions

Sukhoi fighter jets of the Venezuelan Air Force were seen flying over San Cristóbal, Táchira, Venezuela on 20 February and President Nicolas Maduro ordered paratroopers of the 41st Airborne Brigade, 4th Armored Division, Venezuelan Army on standby on recommendations from the Minister of Interior and Justice, Lieutenant General Miguel Rodríguez Torres.[259][260]

Personnel from the Bolivarian National Police and the Venezuelan National Guard were also seen firing weapons and bombs on buildings where opposition protesters were gathered.[261] During a press conference, Minister of the Interior and Justice Miguel Rodriguez Torres denied allegations of Cuban special forces known as the "Black Wasps" of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces assisting the Venezuelan government with protests saying that the only Cubans in Venezuela were helping with medicine and sports.[262]

The allegations that members of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces were in Venezuela began when many people reported images of a military transport plane deploying uniformed soldiers alleged to be Cuban.[263] On 23 February, about 30 military units arrived at the residence of retired brigadier general Ángel Vivas to arrest him for allegedly "training" protestors to place barbed wire over the roads to injure government forces and pro-government protestors, resulting in one fatality in the process and many more wounded.[189][264] According to CBC, Vivas "rose to prominence in 2007 when he resigned as head of the Defence Ministry's engineering department rather than order his subalterns to swear to the Cuban-inspired oath 'Socialist Fatherland or death'."[265] Vivas reported that "Cubans and thugs" were attacking his house and moments later appeared atop the roof of his house wearing a flak jacket along with an assault rifle saying "Come find me Maduro!". National Guardsmen made a barricade in front of Vivas' house but neighbors and supporters defended Vivas by placing a barricade of vehicles in front of the troops. The troops retreated without arresting Vivas after the citizens refused to leave the area.[266][267][268][269] Vivas later explained why he thought Venezuelans needed to defend the country from foreigners, saying "Cubans are in all structures of the Venezuelan state" and also explained that he told protesters to set up barricades in order to defend themselves against attacks from the National Guard.[270]

On 25 February, the military set up a field hospital at Juan Vicente Gómez International Airport in San Antonio del Táchira to treat casualties of the protest actions.[271]

Resolution 8610

On 27 January 2015, the Venezuelan Minister of Defense, Vladimir Padrino López, signed Resolution 8610 which stated that the "use of potentially lethal force, along with the firearm or an other potentially lethal weapon" could be used as a last resort by the Venezuelan armed forces "to prevent disorders, support the legitimately constituted authority and reject any aggression, facing it immediately and the necessary means".[272] The resolution conflicted with Article 68 of the Venezuelan Constitution that states, "the use of firearms and toxic substances to control peaceful demonstrations is prohibited. The law shall regulate the actions of the police and security in the control of public order".[272]

The resolution caused outrage among some Venezuelans which resulted in protests against Resolution 8610, especially after the death of 14-year-old Kluiberth Roa Nunez, which had protests days after his death numbering in the thousands.[273][274][275] Students, academics and human rights groups condemned the resolution.[276] International entities had expressed concern with Resolution 8610 as well, including the Government of Canada which stated that it was "concerned by the decision of the Government of Venezuela to authorize the use of deadly force against demonstrators" while the European Parliament demanded the repeal of the resolution entirely.[277][278]

Days after the introduction of the resolution, Padrino López stated that critics "decontextualized" the decree calling it "the most beautiful document of profound respect for human rights to life and even the protesters".[279] On 7 March 2015, Padrino López later announced that the Venezuelan government was expanding on Resolution 8610 to give more detailed explanations and that the decree "should be regulated and reviewed".[280]

Opposition

Opposition allegations

In an op-ed for the New York Times titled “Venezuela’s Failing State," Lopez lamented “from the Ramo Verde military prison outside Caracas" that for the past fifteen years, “the definition of ‘intolerable’ in this country has declined by degrees until, to our dismay, we found ourselves with one of the highest murder rates in the Western Hemisphere, a 57 percent inflation rate and a scarcity of basic goods unprecedented outside of wartime.” The economic devastation, he added, “is matched by an equally oppressive political climate. Since student protests began on Feb. 4, more than 1,500 protesters have been detained, more than 30 have been killed, and more than 50 people have reported that they were tortured while in police custody,” thus exposing “the depth of this government's criminalization of dissent.” Addressing his incarceration, López recounted that on February 12, he had “urged Venezuelans to exercise their legal rights to protest and free speech – but to do so peacefully and without violence. Three people were shot and killed that day. An analysis of video by the news organization Últimas Noticias determined that shots were fired from the direction of plainclothes military troops.” Yet after the protest, “President Nicolás Maduro personally ordered my arrest on charges of murder, arson and terrorism….To this day, no evidence of any kind has been presented.”[49]

The student leader at University of the Andes marched with protesters and delivered a document to the Cuban Embassy saying, "Let's go to the Cuban Embassy to ask them to stop Cuban interference in Venezuela. We know for a fact that Cubans are in the barracks' and Miraflores giving instructions to suppress the people."[281][282]

The opposition demonstrations that followed have been called by some as "Middle Class Protests".[283] However, some lower class Venezuelans told student protesters visiting them that they also want to protest against the "worsening food shortages, crippling inflation and unchecked violent crime" but are afraid to since pro-government groups known as "colectivos" had "violently suppressed" demonstrations and had allegedly killed some opposition protesters too.[284]

On 19 February, the MUD leader Henrique Capriles came from his silence about the occurring protests and confronted Francisco Ameliach, government officials and denounced the violence the government was using on the protesters.[285] Henrique Capriles said he did not attend the National Peace Conference on 26 February because he did not want dialogue until he saw "results" from the government saying that, "it is the government that has to listen to our people, not the people listen to the government".[286] Juan Requesens, leader of a student movement, called on the Catholic Church to mediate the situation in the country and help guarantee that human rights of Venezuelans will not be violated in the future.[287]

A group of women by the name "Mujeres por la Vida" gathered to remind Venezuelans of those killed during the protest with opposition leader María Corina Machado saying, "Mr. Maduro and his regime, want to bury the faces of young Venezuelans who have been killed for their repression, their memory and their names, and thus their guilt in each of these events that have left wounded, killed, persecuted and tortured".[288]

Carnaval protests

Beaches that were typically full of celebrations during the beginning of lent for Carnaval were empty due to the opposition protests and their call for the rejection of celebrating during such times.[289] Protests continued during the Carnaval holiday after President Nicolas Maduro declared nearly a week of holiday events.[290]

Public opinion

Public support of protests

Since the outset of the protests, peaceful daytime demonstrations advocating for policy changes and "redress of misgovernment" have received widespread support among the public.[291] However, calls for regime change have been met with minimal backing while opposition leaders have struggled to win over politically-unaffiliated Venezuelans and members of the lower classes.

Support by the poor

Protests like this by the poor are really new. The opposition always claimed they existed before, but when you talked to the demonstrators, they were all middle class. But now, it is the poorest who are suffering the most.

The majority of protests were originally limited to more affluent areas of major cities with many working-class citizens thinking that the protests were unrepresentative of them and not working in their interests.[291] This was especially evident in the capital Caracas, where in the wealthier east side of the city, protests widely disrupted daily activities, while life in the poorer west side of the city—hit especially hard by the country's economic struggles— largely continued as normal.[39] The New York Times describes this "split personality" as representative of a long-standing class divide within the country and a potentially crippling fault within the anti-government movement, recognized both by opposition leaders and President Maduro.[38] Later in the protests, however, many in Venezuela's slums that are seen as "bulwarks of [government] support" thanks to social welfare programs, supported the protesters due to frustrations over crime, shortages, and inflation[293] and increasingly began to protest and loot as the situation in Venezuela continuously deteriorated.[292]

In some poor neighborhoods like Petare in western Caracas, residents that had benefitted from such government programs, joined protests against inflation, high murder rates and shortages.[294] Demonstrations in some poor communities remain rare, partially out of fear of armed colectivos acting as community enforcers and distrust of opposition leaders. An Associated Press investigation that followed two students encouraging anti-government support in poor districts found much discontent among the lower classes, but those Venezuelans were generally more worried about possibly losing pensions, subsidies, education, and healthcare if the opposition were to gain power, and many stated they felt leaders on both sides were only concerned with their own interests and ambitions.[293] The Guardian has also sought out viewpoints from the Venezuelan public. Respondents reiterated many of the core protest themes for their protester support: struggles with shortages in basic goods; crime; mismanagement of oil revenue; international travel struggles caused by difficulties in buying airline tickets and the "bureaucratic nightmare" of buying foreign currency; and frustration over the government's rhetoric regarding the alleged "far-right" nature of the opposition.[295] Others offered a variety of reasons for not joining the protests, including: support for the government due to improvements in education, healthcare, and public transportation; pessimism over whether Maduro's ouster would lead to meaningful changes; and the belief that a capitalist model would be no more effective than a socialist model in a corrupt government system.[296]

Protest coverage

Public support for the protests has also been affected by media coverage. Some outlets have downplayed, and sometimes ignored, the larger daytime protests, allowing the protest movement to be defined by its "tiny, violent guarimbero clique," whose radicalism undermines support for the mainline opposition and seemingly reinforces the government's narrative of "fascists" working to overthrow the government[291] in what Maduro described as a "slow motion coup."[39] An activist belonging to the Justice First party said, "Media censorship means people here only know the government version that spoiled rich kids are burning down wealthy parts of Caracas to foment a coup," creating a disconnect between opposition leaders and working-class Venezuelans that keeps protest support from spreading.[39]

Analysis of support

Some Venezuelans contend that the protests—seen as "rich people trying to get back lost economic perks"—have only served to unite the poor in defense of the revolution.[39] Analysts such as Steve Ellner, a political science professor at the University of the East in Puerto La Cruz, have expressed doubt over the protests' ultimate effectiveness if the opposition cannot create broader social mobilization.[39] Eric Olson, associate director for Latin America at the Woodrow Wilson International Center, said disruption caused by protestors had allowed Maduro to use the "greedy economic class" as a scapegoat, which has been an effective narrative for gaining support because people "are more inclined to believe conspiracy theories of price gouging than the intricacies of underlining economic policies."[39]

Poll and survey data

During the 2014 protests, various international and domestic opinion organizations showed the concerns of Venezuelans.

Alfredo Keller & Associates

In an early 2014 survey by Alfredo Keller & Associates, 64% of Venezuelans thought the government under President Maduro was worse than under President Chavez with only 39% of the population supporting President Maduro. 69% believed that the current situation was due to the Bolivarian government. 43% agreed that the government must leave constitutionally while 37% disagreed. In cases of various debates, 56% agreed with the opposition and 38% agreed with the government. 57% of Venezuelans disliked President Maduro. Venezuelans had positive opinions on Democratic Unity Roundtable, Fedecamaras and the United States while they had negative opinions on the United Socialist Party of Venezuela and the Government of Cuba.[297][298][299][300] In an Alfredo Keller & Associates June survey, 67% of those questioned found the situation in the country negative, 60% did not believe socialism turned Venezuela into a "world power" and 69% did not believe the Venezuelan government or the economy was successful. Respondents also said that if elections were held at the time, 42% would vote for MUD while 35% would vote for PSUV.[301]

Croes, Gutierrez & Associates

A Venebarometro survey by Croes, Gutierrez & Associates, 50.9% said that the government under President Maduro had done a bad job at managing the country. 54.3% distanced themselves from President Maduro's government. 52.9% thought the arrest of Leopoldo Lopez was unjust. 69.7% believed the situation in the country was bad with insecurity being the largest principal problem. 51.3% of Venezuelans believed the government and President Maduro was responsible for the problems in Venezuela. 67.2% thought the protests were fair. 60.5% believed human rights violations occurred from the government. 69.2% said that the protests helped show flaws in President Maduro's government. 65.3% did not believe that colectivos should go to the streets to defend the government of President Maduro.[302][303]

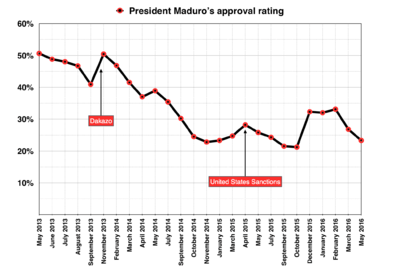

Datanálisis

Sources: Datanálisis

Luis Vicente León, the president of Datanálisis, announced on April 6 his findings that 70% who supported the protests at their start turned to 63% of Venezuelan rejecting the form of protests. He also announced that the results of his latest opinion studies showed President Maduro at between 42% and 45% popularity, while no opposition leader surpassed 40%.[304] Another Datanálisis poll released on 5 May found that 79.5% of Venezuelans evaluated the country's situation as "negative". Maduro's disapproval rating had risen to 59.2%, up from 44.6% on November 2013. It also found that only 9.6% of the population would support the re-election of Maduro in 2019. The poll revealed that the Democratic Unity Roundtable had an approval rating of 39.6% compared to 50% of those who disapproved it; while the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela had a 37.4% approval rating, and a disapproval rating of 55%.[305]

In a poll released on May 5, 2015, Datanálisis found that 77% of respondents did not intend to participate in peaceful protests, while 88% would not participate in protests involving barricades. León attributed this to the criminalization of the protests, fears of government repression, and frustration over the protests' goals not being achieved. The poll also found that 70% would participate in upcoming parliamentary elections—a possible "exhaust valve" for channeling popular discontent—but León noted this represented weakened participation and that Venezuelans were preoccupied with economic and social issues.[306]

Datos

In March 2014, a survey conducted by Datos, a Venezuelan group focusing on public opinion and consumers, found that more than half of Venezuelans blamed the Maduro government for the country's problems, and that 64% believed the government should get out of power constitutionally as soon as possible.[307] When Venezuelans were asked about the overall situation in the country, 72.0% found the situation negative with more than half thinking it had worsened since President Maduro took office in 2013.[90][91][308]

Gallup