Operation Lentil (Caucasus)

.svg.png)

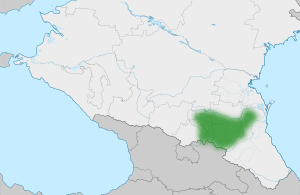

Operation Lentil (Russian: Чечевица, Chechevitsa; Chechen: Aardax, Ardakh) was the Soviet expulsion of the whole of the Vainakh (Chechen and Ingush) populations of the North Caucasus to Central Asia during World War II. The expulsion, preceded by the 1940–1944 insurgency in Chechnya, was ordered on 23 February 1944 by NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria after approval by Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, as a part of Soviet forced settlement program and population transfer that affected several million members of non-Russian Soviet ethnic minorities between the 1930s and the 1950s.

The deportation encompassed their entire nations, well over 500,000 people, as well as the complete liquidation of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Tens (or possibly hundreds) of thousands of Chechens and Ingushes died or were killed during the round-ups and the transportation, and in their early years in exile. The survivors would not return to their native lands until 1957. Many in Chechnya and Ingushetia classify it as an act of genocide, as did the European Parliament in 2004.

Background

During World War II, despite the fact that about 40,000 Chechens and Ingush fought in the Red Army (50 of them received the highest recognition of the Hero of the Soviet Union), the Soviet government accused them of cooperating with the Nazi invaders, who had controlled the western parts of Chechnya-Ingushetia for several months of the 1942/1943 winter. It was claimed that some Chechens were eager to show the Nazis mountain passes leading to Azerbaijan SSR, whose oil reserves were the goal of Operation Blue (Fall Blau). In 1940, another Chechen insurgency, led by Khasan Israilov, started in Galanchozh. In February 1942, Mairbek Sheripov's group rebelled in Shatoysky and Itum-Kalinsky Districts. They united with Israilov's army to rebel against the Soviet system. The key period of the Chechen guerilla war started in August–September 1942, when the German troops approached Ingushetia, and ended in the summer-autumn of 1943, with the Soviet counter-offensive that drove the Wehrmacht from the North Caucasus.[1]

Various authors dispute the Chechens' ties with the Germans.[2][3][4] What is certain is that they did have contact with the Germans. However, there were profound ideological differences between the Chechens and the Nazis (self-determination versus imperialism), neither trusted the other, there was an influential Jewish clan among the Chechens (who were not considered as "Aryan" to begin with), the German courting of the Terek Cossacks was not pleasing at all to the Chechens (their traditional enemies which with they still had numerous land disputes and other conflicts) and Israilov certainly had a strong dislike for Hitler. Sheripov reportedly gave the Ostministerium a sharp warning that "if the liberation of the Caucasus meant only the exchange of one colonizer for another, the Caucasians would consider this [a theoretical fight pitting Chechens and other Caucasians against Germans] only a new stage in the national liberation war."[5] These authors note there were also many Chechens (17,413) in the Red Army (and, coincidentally, also much less than the number of Russians and Cossacks fighting for the Nazis).[6][7][8] However, others argue that the number of Chechens in the military was much smaller than other groups, demonstrating that there was widespread desertion and draft evasion. The number of Chechens and Ingush killed or missing from service in the Red Army numbered about 2,300 men, compared to how the much less numerous Buryats suffered 13,000 deaths and 11,000 deaths among the Ossetians.[9]

On orders from Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the NKVD, the entire Chechen and Ingush population of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic were to be deported by freight trains to remote areas of the Soviet Union. The operation was called "Chechevitsa" (Operation Lentil),[10] its first two syllables pointing a finger at its intended targets (though while the Chechens were the main targets, they were not the only victims). The operation is referred to by Chechens often as "Aardakh" (the Exodus). Alexander Yakovlev argued that the eviction of the population was a part of Stalin's program designed for suppression of rebellions in the Soviet Union. In October 1943, a group of NKVD officers led by Bogdan Kobulov was sent to Chechnya to prepare materials for justification of repressions. In November, they sent a letter to Beria claiming that "there are 38 religious groups in Chechnya with membership of at least 20,000 people, who conduct active anti-Soviet work, help the bandits and German saboteurs, and call for armed resistance to the Soviet power."[11] Beria then ordered to prepare the operation. The Chechen-Ingush republic was never occupied by the German army, therefore the repressions were officially justified by "an armed resistance to Soviet power".[1][12]

The operation (Aardakh)

On October 13, 1943, Operation Lentil commenced when about 120,000 men were moved into Checheno-Ingushetia, supposedly for mending bridges. On February 23, 1944 (on Red Army Day), the entire population was summoned to local Party buildings where they were told they were going to be deported as punishment for their alleged collaboration with the Germans. The inhabitants were rounded up and imprisoned in Studebaker trucks, before being packed into unheated and uninsulated freight cars.[13][14] Some 40% to 50% of the deportees were children.[15]

Many times, resistance was met with slaughter, and in one such instance, in the aul of Khaibakh, about 700 people were locked in a barn and burned to death by NKVD General Mikheil Gveshiani, who was praised for this and promised a medal by Beria. Many people from remote villages were executed per Beria's verbal order that any Chechen or Ingush deemed 'untransportable should be liquidated' on the spot.[16] An eyewitness recalled the actions of the NKVD forces:[17]

They combed the huts to make sure there was no one left behind... The soldier who came into the house did not want to bend down. He raked the hut with a burst from his submachine gun. Blood trickled out from under the bench where a child was hiding. The mother screamed and hurled herself at the soldier. He shot her too. There was not enough rolling stock. Those left behind were shot. The bodies were covered with earth and sand, carelessly. The shooting had also been careless, and people started wriggling out of the sand like worms. The NKVD men spent the whole night shooting them all over again.

Throughout the North Caucasus, about 700,000 (according to Dalkhat Ediev, 724,297,[18] of which the majority, 479,478, were Chechens, along with 96,327 Ingush, 104,146 Kalmyks, 39,407 Balkars and 71,869 Karachays) were deported. Many died en route, and the extremely harsh environment of exile (especially considering the amount of exposure) killed many more. The NKVD, supplying the Russian perspective, gives the statistic of 144,704 people killed in 1944–48 alone (death rate of 23.5% per all groups), though this is dismissed by many authors such as Tony Wood, John Dunlop, Moshe Gammer and others as a significant understatement.[19] Estimates for deaths of the Chechens alone (excluding the NKVD figures), range from about 170,000 to 200,000,[20][21][22][23] thus ranging from over a third of the total Chechen population to nearly half being killed in those 4 years alone (rates for other groups for those four years hover around 20%). Certain modern Russian sources, however, dispute that there were deliberately harsh conditions set for Chechens as opposed to other nationalities, and point to population growth in the 1959 census.[24]

Aftermath

The Checheno-Ingush ASSR was dissolved and transformed into Grozny Oblast, which included also the Kizlyarsky District and Naursky Raion, and parts of it were given to North Ossetia (part of Prigorodny District), Georgian SSR and Dagestan ASSR. Most of the empty housing was given to refugees from war-raged western Soviet Union.[25] Abandoned houses were settled by newcomers, only the Mountain Jews[26] and Meskhetian Turks, both of which groups had previously lived in the area, refused to settle in foreign houses. Names of repressed nations were totally erased from all books and encyclopedias.[16] By the next summer, a number of Chechen and Ingush placenames were replaced with Russian ones; mosques and graveyards were destroyed, and a massive campaign of burning numerous historical Nakh language books and manuscripts was near complete.[27][28] Many families were divided and not allowed to travel to each other even if they found out where their relatives were.[25] Some of Vainakh settlements were totally deleted from maps and encyclopedias. Many gravestones were destroyed in places that were renamed to be given Russian names, along with pretty much the whole library of Vainakh medieval writing (in Arabic and Georgian script) about the lands and peoples of Chechnya and Ingushetia and their peoples (leaving their ancestors and the world depleted of what was more or less the only source of central Caucasian literature and historical texts, except for sparse texts about them that were written by Georgians).[29][30]

The return

In 1957, four years after Stalin's death in 1953, the Soviet Council of Ministers, passed a decree allowing repressed nations to freely travel in the Soviet Union. Many exiled Chechens took this opportunity to return to their ancestral land. Chechens and Ingush had already been returning to their homeland in the tens of thousands for two years before the announcement; the rate of return increased exponentially after Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin in 1956. By 1959, almost all the Chechens and Ingush had returned.

In 1958, the Chechen-Ingush ASSR was officially restored by a decree direct from Moscow, but in previous 1936 borders. North Ossetia kept the Prigorodny District and Dagestan kept the Novolaksky District (historically a part of Akkia, the homeland of the Akki Chechens), while the Chechen-Ingush ASSR was "compensated" with the Naursky and Shelkovsky Districts.

When the Chechens and Ingush returned to their homeland, they found other peoples living, quite literally, in their homes, and viewed these other ethnicities (Ossetians, Russians, Laks, Kumyks and Avars) with hostility. Conflicts between Ossetians and Ingush in Prigorodny, and between Russians/Cossacks and Chechens in northern Chechnya, simmered and threatened to boil over into violence many times. In the case of Akkia, there was more understanding between the two sides, not because of their historical contacts and shared religion, but rather because the Chechens knew that the Dagestanis had not moved onto their land by choice, but rather were forced to.[31] However, the dispute over Akkia was not resolved, despite efforts by both sides to find a middle ground.

Many returning Chechens were settled in the lowland steppe regions, and in Grozny itself rather than the mountainous districts. The goal of this was to try to forcefully assimilate the Chechens by keeping them away from the mountains and reminders of "their ancient struggles", and to keep them mixed in with supposedly more loyal Russians so they could not rebel without a counter-force present.[32][33] Ultimately, the attempt to make Checheno-Ingushetia more multi-ethnic in order discourage potential uprisings failed due to the higher birthrate of the Vainakhs.[34] Instead it deepened and renewed ethnic conflict between Chechens and Russians. The Russians, angered by issues over land ownership and job competition, rioted as early as 1958,[35] seizing government buildings and demanding either a restoration of Grozny Oblast, or a creation of a non-titular autonomy, re-deportation of the Chechens and Ingush, establishment of "Russian power", mass search and disarming of Vainakh, before Soviet law enforcement dispersed the rioters.[36][37] Although the riot was dispersed and denounced as "chauvinistic", afterward the republican government made special efforts to please the Russian populace, including mass discrimination against the Chechens aimed at preserving the privileged position of the Russians.[37]

Chechens were greatly disadvantaged after being allowed to return. There were no Chechen-language schools, leading to a lack of education of the populace (which did not universally understand Russian).[38] According to sociologist Georgi Derluguyan, the Checheno-Ingush Republic's economy was divided into two spheres, in which the Russian sphere had all the jobs with higher salaries,[39] while those in the non-Russians sphere were systematically kept out of all government positions. This system, combined with large population growth for the non-Russians, caused the growth of organized crime and emigration to other republics as escapes from poverty.

Remembrance

In 1991, Chechen President Dzhokhar Dudayev made political capital by, in a symbolic move, sending out officials to gather these lost gravestones (that had been used by the Soviets for the construction of pedestrian footpasses and foundations of pig pens), many of which had lost their original inscriptions, and to construct out of them a memorial in the center of Grozny. The memorial was made to symbolize both Chechen remorse for the past as well as the desire to, in the name of the dead ancestors, fashion the best possible Chechen Republic out of their land and work hard towards the future. It bears an engravement, reading: "We will not break, we will not weep; we will never forget." Tablets bore pictures of the sites of massacres, such as Khaibakh.[40][41] The memorial was damaged during the subsequent Russo-Chechen wars. It has been later moved and dismantled by Ramzan Kadyrov's pro-Moscow government, sparking much controversy.[40][42]

Forced deportation constitutes an act of genocide according to the IV Hague Convention of 1907 and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of the U.N. General Assembly (adopted in 1948). In this case this was acknowledged by the European Parliament as an act of genocide in 2004;[43] experts of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum cited the events of 1944 for a reason of placing Chechnya on their genocide watch list for its potential for genocide.[44] The separatist government of Chechnya also recognizes it as genocide, as do Ingush nationalists. Members of the Chechen diaspora and their supporters promote February 23 as World Chechnya Day to commemorate the victims.[45]

See also

References

- 1 2 Jeffrey Burds. The Soviet War against ‘Fifth Columnists’: The Case of Chechnya, 1942–4 // Journal of Contemporary History, Vol 42(2), 2007, P. 16, 26

- ↑ Avtorkhanov. Chechens and Ingush. p183

- ↑ Wood, Tony. Chechnya: The Case for Independence.p36

- ↑ Gammer. Lone Wolf and Bear. Pages 161-165

- ↑ Avtorkhanov. Chechens and Ingush. Page 183.

- ↑ Dunlop, John. Russia Confronts Chechnya. Page 60

- ↑ Wood, Tony. Chechnya. Page 36

- ↑ Nekrich, Aleksander. Punished Peoples. Pages 36-38

- ↑ http://militera.lib.ru/research/pyhalov_dukov/02.html

- ↑ Wood, Tony. Chechnya:The Case for Independence. Pages 32-39

- ↑ Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev Time of darkness, Moscow, 2003, ISBN 5-85646-097-9, pages 205-206 (Russian: Яковлев А. Сумерки. Москва: Материк 2003 г.

- ↑ Execute everyone who can not be transported (Russian) Novaya Gazeta

- ↑ Dunlop, Russia Confronts Chechnya, p65

- ↑ Gammer, The Lone Wolf and the Bear, p170

- ↑ Dunlop, John B. (1998). Russia confronts Chechnya: roots of a separatist conflict. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-521-63619-3.

- 1 2 "The Soviet War against ‘Fifth Columnists’: The Case of Chechnya, 1942–4" by Jeffrey Burds, p.39

- ↑ Edvard Radzinsky Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives, Anchor, (1997) ISBN 0-385-47954-9, page 503

- ↑ Ediev, Dalkhat. Demograficheskie poteri deportirovannykh narodov SSSR, Stavropol 2003, Table 109, p302

- ↑ Wood, Tony. Chechnya: the Case for Independence. page 37-38

- ↑ Nekrich, Punished Peoples

- ↑ Dunlop. Russia Confronts Chechnya, pp 62-70

- ↑ Gammer. Lone Wolf and the Bear, pp166-171

- ↑ Soviet Transit, Camp, and Deportation Death Rates

- ↑ Пыхалов И. В. За что Сталин выселял народы? Сталинские депор- тации — преступный произвол или справедливое воз- мездие? — М.: Яуза-пресс, 2008. p. 317

- 1 2 Дешериев Ю. Жизнь во мгле и борьбе: О трагедии репрессированных народов. ISBN 5-86020-238-5

- ↑ Rouslan Isacov, Kavkaz Center 01.02.2005

- ↑ Gammer, The Lone Wolf and the Bear, p182

- ↑ Jaimoukha. Chechens. p212

- ↑ Jaimoukha. Chechens. Page 212

- ↑ Gammer, Moshe. Lone Wolf and Bear. Page 170

- ↑ ГУ ЦГА РД. Ф. р-168. Оп. 35. Д. 21. Л. 189, 191.

- ↑ Karcha, Soviet Propaganda. Page 8

- ↑ Dunlop, John B. Russia confronts Chechnya: roots of a separatist conflict. Pages 79-80

- ↑ Nekrich. Punished Peoples. Pages 157-8

- ↑ Операция "Чечевица"

- ↑ Dunlop, John B. Russia confronts Chechnya: Roots of a Separatist Conflict. Pages 80-81

- 1 2 (Russian)Matveyev, Oleg. Русский бунт в Грозном (Russian Riot in Grozny). 30 April 2000. Available for viewing online: http://www.ng.ru/style/2000-08-30/8_bunt.html

- ↑ Dunlop, John B. Russia confronts Chechnya. Page 81, 88

- ↑ Derluguyan, Georgi (2005). Bourdieu's Secret Admirer in the Caucasus. University of Chicago Press. pp. 244–5. ISBN 978-0-226-14283-8.

- 1 2 CanWest MediaWorks Publications. Relocation of Chechen 'genocide' memorial opens wounds. June 4th, 2008

- ↑ Lieven, Anatol. Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian power. Published 1998. Page 321

- ↑ Russia's Chechnya moves memorial, citizens complain, Reuters, June 3, 2008

- ↑ UNPO: Chechnya: European Parliament recognises the genocide of the Chechen People in 1944

- ↑ Speaker Series -- The 60th Annniversary of the 1944 Chechen and Ingush Deportation: History, Legacies, Current Crisis

- ↑ Press-Release: February 23, World Chechnya Day - Save Chechnya Campaign - Let's Break the Silence for Justice in Chechnya

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

| Issues |

| Documented instances |

|

| Related topics |

External links

- World Chechnya Day.org - A website of Chechen diaspora promoting observance of February 23 as the anniversary of the genocide against the Vaynakh people. It also has a wealth of information (in the history section) about the conditions of the deportation, with numerous quotes.