South-West Africa

| South-West Africa | ||||||||||

| Suidwes-Afrika Zuidwest-Afrika Südwestafrika | ||||||||||

| Mandate of South Africa | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

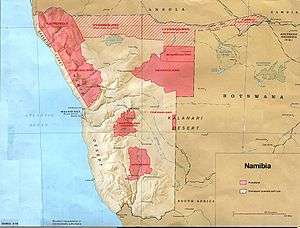

Location of South-West Africa | ||||||||||

| Capital | Windhoek | |||||||||

| Languages | English, Afrikaans, Khoekhoe, Dutch (1915–1983) and German (1884–1990) | |||||||||

| Political structure | League of Nations Mandate | |||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| • | Established | 1915 | ||||||||

| • | Treaty of Versailles | 28 June 1919 | ||||||||

| • | Independence | 21 March 1990 | ||||||||

| Currency | South West African pound (1920–61) South African rand (1961–90) | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Namibia |

|

|

|

South-West Africa (Afrikaans: Suidwes-Afrika; Dutch: Zuidwest-Afrika; German: Südwestafrika) was the name for modern-day Namibia when it was ruled by the German Empire and later South Africa.

German colony

As a German colony from 1884, it was known as German South-West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika). Germany had a difficult time administering the territory, which experienced many insurrections, especially those led by guerilla leader Jacob Morenga. The main port, Walvis Bay, and the Penguin Islands were annexed by Britain in 1878, becoming part of the Cape Colony in 1884.[1] Following the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, Walvis Bay became part of the Cape Province.[2]

As part of the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty in 1890, a corridor of land taken from the northern border of Bechuanaland, extending as far as the Zambezi river, was added to the colony. It was named the Caprivi Strip (Caprivizipfel) after the German Chancellor Leo von Caprivi.[3]

South African rule

In 1915, during South-West Africa Campaign of the First World War, South Africa captured the German colony. After the war, it was declared a League of Nations Class C Mandate territory under the Treaty of Versailles, with the Union of South Africa responsible for the administration of South-West Africa. From 1922, this included Walvis Bay, which, under the South-West Africa Affairs Act, was governed if it were part of the mandated territory.[4] South-West Africa remained a League of Nations Mandate until World War II.

The Mandate was supposed to become a United Nations Trust Territory when League of Nations Mandates were transferred to the United Nations following the Second World War. The Prime Minister, Jan Smuts, objected to South-West Africa coming under UN control and refused to allow the territory's transition to independence, instead seeking to make it South Africa's fifth province in 1946.[5]

Although this never occurred, in 1949, the South-West Africa Affairs Act was amended to give representation in the Parliament of South Africa to whites in South-West Africa, which gave them six seats in the House of Assembly and four in the Senate.[6]

This was to the advantage of the National Party, which enjoyed strong support from the predominantly Afrikaners and ethnic German white population in the territory.[7] Between 1950 and 1977, all of South-West Africa's parliamentary seats were held by the Nationalists.[8]

An additional consequence of this was the extension of apartheid laws to the territory.[9] This gave rise to several rulings at the International Court of Justice, which in 1950 ruled that South Africa was not obliged to convert South-West Africa into a UN trust territory, but was still bound by the League of Nations Mandate with the United Nations General Assembly assuming the supervisory role. The ICJ also clarified that the General Assembly was empowered to receive petitions from the inhabitants of South-West Africa and to call for reports from the mandatory nation, South Africa.[10] The General Assembly constituted the Committee on South-West Africa to perform the supervisory functions.[11]

In another Advisory Opinion issued in 1955, the Court further ruled that the General Assembly was not required to follow League of Nations voting procedures in determining questions concerning South-West Africa.[12] In 1956, the Court further ruled that the Committee had the power to grant hearings to petitioners from the mandated territory.[13] In 1960, Ethiopia and Liberia filed a case in the International Court of Justice against South Africa alleging that South Africa had not fulfilled its mandatory duties. This case did not succeed, with the Court ruling in 1966 that they were not the proper parties to bring the case.[14][15]

UN mandate terminated

There was a protracted struggle between South Africa and forces fighting for independence, particularly after the formation of the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) in 1960.

In 1966, the General Assembly passed resolution 2145 (XXI) which declared the Mandate terminated and that the Republic of South Africa had no further right to administer South-West Africa.[16] In 1971, acting on a request for an Advisory Opinion from the United Nations Security Council, the ICJ ruled that the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia was illegal and that South Africa was under an obligation to withdraw from Namibia immediately. It also ruled that all member states of the United Nations were under an obligation not to recognise as valid any act performed by South Africa on behalf of Namibia.[17]

South-West Africa became known as Namibia by the UN when the General Assembly changed the territory's name by Resolution 2372 (XXII) of 12 June 1968.[18] SWAPO was recognised as representative of the Namibian people and gained UN observer status[19] when the territory of South-West Africa was already removed from the list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.

In 1977, South Africa transferred control of Walvis Bay back to the Cape Province, thereby making it an exclave.[20]

The territory became the independent Republic of Namibia on 21 March 1990, although Walvis Bay and the Penguin Islands were only incorporated into Namibia in 1994.[21]

Bantustans

The South African authorities established 10 bantustans in South-West Africa in the late 1960s and early 1970s in accordance with the Odendaal Commission, three of which were granted self-rule.[22] These bantustans were replaced with separate ethnicity based governments in 1980.

The bantustans were:

- Basterland

- Bushmanland

- Damaraland

- East Caprivi (self-rule 1976)

- Hereroland (self-rule 1970)

- Kaokoland

- Kavangoland (self-rule 1973)

- Namaland

- Ovamboland

- Tswanaland

See also

- List of colonial heads of Namibia (South-West Africa)

- History of Namibia

- South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO)

- South-West African Territorial Force (SWATF)

- South West African Police (SWAPOL)

- Koevoet

References

- ↑ Succession of States and Namibian territories, Y. Makonnen in Recueil Des Cours, 1986: Collected Courses of the Hague Academy of International Law, Academie de Droit International de la Haye, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1987, page 213

- ↑ Debates of Parliament, Hansard, Volume 9, Issues 19-21, Government Printer, 1993, page 10179

- ↑ Caprivi Strip | Namibia. Namibian.org. Retrieved on 2012-12-18.

- ↑ Walvis Bay: exclave no more, Ieuan Griffiths, Geography, Vol. 79, No. 4 (October 1994), page 354

- ↑ The South-West Africa/Namibia Dispute: Documents and Scholarly Writings on the Controversy Between South Africa and the United Nations, John Dugard, University of California Press, 1973, page 124

- ↑ Official Documents of the 4th Session of the United Nations General Assembly, United Nations, 1949, page 11

- ↑ Afrikaner Politics in South Africa, 1934-1948, Newell M. Stultz, University of California Press, 1974, page 161

- ↑ Mediating Conflict: Decision-making and Western Intervention in Namibia, Vivienne Jabri, Manchester University Press, 1990, page 46

- ↑ Witness from the frontline: aggression and resistance in Southern Africa, Ben Turok Institute for African Alternatives, 1990, page 86

- ↑ International Status of South-West Africa – Advisory Opinion at the Wayback Machine (archived October 2, 2006)

- ↑ List of United Nations Organisations and Resolutions concerning Namibia

- ↑ Voting Procedure on Questions Relating to Reports and Petitions Concerning the Territory of South-West Africa – Advisory Opinion at the Wayback Machine (archived October 2, 2006)

- ↑ Admissibility of Hearings of Petitioners by the Committee on South-West Africa – Advisory Opinion at the Wayback Machine (archived October 2, 2006)

- ↑ South-West Africa Cases (Preliminary Objections) Ethiopia v. South Africa and Liberia v. South Africa at the Wayback Machine (archived October 2, 2006)

- ↑ South-West Africa Cases (Second Phase) Ethiopia v. South Africa and Liberia v. South Africa at the Wayback Machine (archived October 2, 2006)

- ↑ UN General Assembly, res n° 2154 (XXI), 17 November 1966. Available at http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/21/ares21.htm [recovered october 1, 2015]

- ↑ Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South-West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970) – Advisory Opinion

- ↑ Legal Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs

- ↑ UNGA Resolution A/RES/31/152 Observer status for the South West Africa People's Organisation

- ↑ The Green and the dry wood: The Roman Catholic Church (Vicariate of Windhoek) and the Namibian socio-political situation, 1971-1981, Oblates of Mary Immaculate, 1983, page 6

- ↑ Treaty between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Republic of Namibia with respect to Walvis Bay and the off-shore Islands, 28 February 1994

- ↑ World Statesman

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)