Battle of Núi Bop

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Nui Bop (3–4 January 1885) was a French victory during the Sino-French War. The battle was fought to clear Chinese forces away from the French forward base at Chu, and was an essential preliminary to the Lang Son Campaign in February 1885.[1]

Background

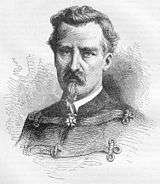

In late September 1884 large detachments of the Guangxi Army advanced from Lang Son and probed into the Luc Nam valley, announcing their presence by ambushing the French gunboats Hache and Massue on 2 October. General Louis Brière de l'Isle, the French commander-in-chief, responded immediately, transporting nearly 3,000 French soldiers to the Luc Nam valley aboard a flotilla of gunboats and attacking the Chinese detachments before they could concentrate. In the Kep Campaign (2 to 15 October 1884), three French columns under the overall command of General François de Négrier fell upon the separated detachments of the Guangxi Army and successively defeated them in engagements at Lam (6 October), Kép (8 October) and Chu (10 October).

In the wake of these French victories the Chinese fell back to Bac Le and Dong Song, and de Négrier established important forward positions at Kep and Chu, which threatened the Guangxi Army's base at Lang Son. Chu was only a few miles southwest of the Guangxi Army's advanced posts at Dong Song, and on 16 December 1884 a strong Chinese raiding detachment ambushed two companies of the Foreign Legion just to the east of Chu, at Ha Ho. The legionnaires fought their way out of the Chinese encirclement, but suffered a number of casualties and had to abandon their dead on the battlefield. De Négrier immediately brought up reinforcements and pursued the Chinese, but the raiders made good their retreat to Dong Song.[2]

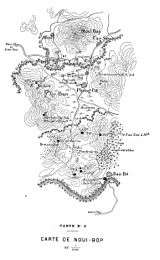

Although the Guangxi Army had been forced to retreat in the October battles, its commanders had not given up all hope of breaking into the Delta. Driven partly by sheer hunger and partly by the knowledge that the French would sooner or later move against Lang Son, the Chinese renewed their efforts to gain a foothold in the Luc Nam valley in December. The action at Ha Ho was the first indication that a major move was afoot. A week after this engagement a force of 12,000 Chinese troops from the Guangxi Army occupied the distinctive conical hill of Nui Bop, eighteen kilometres to the east of Chu, and began to lay out a large fortified camp. The Chinese force was under the command of Wang Debang, one of the Guangxi Army's more competent generals, who had defeated a French column in June 1884 in the Bac Le ambush.[3]

The famished Chinese soldiers plundered all the villages in the area for food, earning the hatred and resentment of the Tonkinese farmers whose livelihood they were destroying. On 23 December the villagers of Lien Son came to the French headquarters at Chu and alerted Lieutenant-Colonel Donnier to the presence of a large Chinese force around Nui Bop.[4]

The French could not allow a force of 12,000 Chinese to remain at Nui Bop, uncomfortably close to their main base at Chu and threatening the flank of the expeditionary corps when it eventually set off for Lang Son. Brière de l'Isle reinforced the Chu garrison in late December, and in early January 1885 de Négrier was ordered to take the offensive against the Chinese.[5]

De Négrier's column was drawn from both the 1st and 2nd Brigades of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps. It included a marine infantry battalion under the command of chef de bataillon Mahias, de Mibielle’s Turco battalion and two companies of Tonkinese riflemen. The column also included the 111th and 143rd Line battalions and Jourdy and de Saxcé’s batteries.[Note 1]

Battle

3 January

Instead of marching directly east from Chu to attack the Chinese frontally, de Négrier decided to cross to the southern bank of the Luc Nam river and make a wide flank march to come in on the Chinese left. To divert the enemy’s attention while his main column marched around the Chinese, chef de bataillon Diguet's Legion battalion in Chu would demonstrate against their front.[6]

The column set off from Chu at 6 am on 3 January. Commandant Mahias led the advance guard, consisting of his own marine infantry battalion, Jourdy’s battery and the Tonkinese Rifles, while Lieutenant-Colonel Paul-Gustave Herbinger led the main body (the other three infantry battalions and de Saxcé’s battery). A small rearguard protected the baggage train. After a short march the column reached the ford of Kao Ka and crossed to the southern bank of the Luc Nam. The crossing was completed by 8 am, and the column then marched eastwards to the ford of Dao Be. The French had been told that the ford could be crossed easily, but they discovered that the northern bank of the Luc Nam river was more than nine feet high at Dao Be and almost sheer. The crossing took three hours. It was not until 4 pm that the main body of the column was able to resume its march.[7]

While the crossing was still in progress, de Négrier sent Mahias ahead with the advance guard. Mahias pushed on along the path to Phong Cot, and at 4.15 pm reported back that the enemy was in sight. Less than a mile away a long line of Chinese infantry was drawn up across the floor and up the sides of the Phong Cot valley. In front of this force groups of skirmishers had advanced to within 800 metres of the Luc Nam to occupy a wood. The French column had been spotted fording the river, and the delay in completing the crossing had given the Chinese just enough time to prepare to meet its attack. De Négrier had failed to achieve the surprise he had hoped for.[8]

The French column advanced to contact in three lines. The first line consisted of Mahias’ battalion, the Tonkinese Rifles and Jourdy’s battery. The second line contained the 111th and 143rd Line Battalions and de Saxcé’s battery. De Mibielle’s 3rd Algerian Rifle Battalion formed a third line. The French artillery took position on a hill to the right of the path and opened fire on the Chinese skirmishers, while de Négrier gave his orders for the attack. The marine infantry were ordered to attack the wood frontally, while the 143rd Battalion was to climb the hills to the right to flank the enemy’s position and push back the Chinese left wing into the Phong Cot valley. The 111th Battalion and de Mibielle’s Algerians would remain in reserve near the artillery.[9]

Mahias had little trouble in driving the Chinese skirmishers out of the wood. He deployed three of the four companies of his battalion to attack the wood both frontally and from the flank, while holding the fourth company in reserve. Meanwhile, the Tonkinese riflemen took up position on his right to link the marine infantry with the 143rd Battalion. The enemy skirmishers quickly fell back, and reformed on a small hill behind the wood.[10]

Captain Salles, whose company had just helped to clear the wood, pushed on and drove the enemy off the hill. This action took Salles well beyond the other three companies of his battalion and into a hail of Chinese rifle fire from the heights on both sides of the Phong Cot valley, which were held by strong Chinese flanking forces. To disengage Salles’s company it was necessary for the artillery to switch targets while the rest of Mahias’ battalion and the 143rd Battalion attacked on both sides of it to drive back the enemy wings. Salles withdrew his men to the wood, and the marine infantry battalion reformed and consolidated the ground it had won.[11]

Farret's 143rd Line Battalion now delivered its own attack on the enemy right, with two companies in the front line and two in reserve. The advance was difficult, as the Chinese held their positions stubbornly, but eventually the battalion established a lodgement on the high ground close to the enemy positions. However, its movement towards the right had created a hole in the centre of the French line, and a Chinese unit advanced into this gap to counterattack. Lieutenant Desloge, with one of the two reserve companies of the 143rd Battalion, drove off this counterattack and then pushed on to the heights to support the main attack.[11]

The Chinese soldiers facing de Négrier’s men in this part of the field wore a distinctive covering of tawny material with black stripes on their heads and shoulders. They were, the French were later told, from the Imperial Tiger Regiment, a Yellow Banner unit entirely composed of Tartars. As Desloge and his handful of men bore down on them, the Tigers delivered a panicky close-range volley. They fired high, and missed their targets altogether. Before the French could reach them with their bayonets they broke and ran, leaving their dead behind them. They also abandoned their regimental standard, a magnificent flag in yellow silk embroidered with gold.[11]

The leading French units pressed on and cleared the Chinese from the hills around Phong Cot, while the rest of de Négrier’s column continued its crossing of the Luc Nam. The Chinese made a half-hearted attempt to counterattack the 143rd Battalion, but their troops were driven off. By nightfall the entire French column was across the river and in position to the south of Phong Cot.[12]

De Négrier believed that the Chinese were demoralised, and was anxious to seize Phong Cot itself before they could rally. Accordingly, just before midnight, he ordered Herbinger to move forward and occupy the village. The French capture of the nearby hills had made it untenable, and the Chinese had evacuated it under cover of darkness. Herbinger met no resistance, and ordered Faure’s 111th Battalion to garrison the village. Faure placed three of the battalion’s four companies inside Phong Cot and Verdier’s company in a forward position beyond it.[13]

4 January

Just before dawn on 4 January the Chinese made a furious counterattack in an attempt to recapture Phong Cot. The attack was supported by the Chinese artillery in the Western Fort. Within minutes the attackers had surrounded Verdier’s company in its isolated forward position. While his company tried to defend itself with close-range rifle fire Verdier ordered one of his men to try to make his way through the Chinese lines back to Phong Cot and ask for help. A young private soldier named Meffret crept cautiously through the Chinese lines in the fading gloom of night and reached Phong Cot, where he delivered Verdier's message to Lieutenant-Colonel Herbinger.[14]

Herbinger, perhaps believing that Meffret was exaggerating the danger, responded by sending forward from Phong Cot a single section of the 111th Battalion—a mere ten men. Fortunately for Verdier, there were other officers on the field who could better appreciate the gravity of the situation. Captain Tailland, whose marine infantry company was posted on a hill to the west of Phong Cot, could see that Verdier’s company would be annihilated unless it was brought immediate relief. Without waiting for orders, he led his own men to the rescue. By now Verdier’s men were being pressed so closely by the Chinese that their captain ordered them to charge to throw them back. Although Verdier was wounded as he led his men forward, his bold lunge took the Chinese completely by surprise. As the Chinese fell back and regrouped, Tailland's marsouins came up on Verdier's left flank and moved into line alongside Verdier’s men. The two French companies caught their breath, reformed, counterattacked and drove the Chinese off. Verdier and Tailland were both later mentioned in despatches for their courage and initiative.[15]

The Chinese did not attempt to take the offensive again. De Négrier went forward to the heights occupied by the marine infantry and scouted the Chinese positions. The main Chinese defence line consisted of a trench between Phong Cot and the Siou Nien River, which protected the road that ran from Lien Son to Cao Say. This trench was flanked on both sides by two forts on elevated ground (Western Fort and Eastern Fort). Behind the Siou Nien river, on the lower slopes of the Nui Bop massif, were several Chinese forts.[16]

During the morning of 4 January de Négrier directed several French attacks which pushed the enemy back from all his positions. The first French objective was a fort on a hill behind the village of Tay Toun, not far from the marine infantry positions. Mahias's battalion attacked and took this fort with little difficulty. To its right the 111th Battalion, profiting from the confusion in the Chinese ranks caused by Verdier’s counterattack, advanced on the main Chinese positions. The battalion charged the Chinese trench with the bayonet, driving its defenders out with equal ease. Lieutenant de Colomb’s platoon, thoroughly over-excited, pushed on towards a Chinese redoubt defended by several hundred men. Had it attempted to charge this position it would doubtless have been repulsed with heavy losses. However, the river was too deep to cross at this point, and the platoon was forced to halt its advance.[17]

Meanwhile, the 143rd Battalion and the Algerian Rifles were ordered to make a turning movement around the enemy left. The French artillery punished the enemy positions which it took in the flank, since these positions faced southwards towards Chu. At 11.15 am the entire entrenched camp was in French hands. The French took possession of two abandoned Krupp artillery batteries and large quantities of rifles, clothes, tents and food. Several Chinese battle flags were also taken, and a number of mules and horses.[18]

Aftermath

French casualties at Nui Bop were relatively light: 19 dead and 65 wounded. The French wounded included three officers, Captain Verdier and Lieutenant Simoni of the 111th Line Battalion and 2nd Lieutenant Larribe of the Tonkinese Rifles.[19]

The Chinese abandoned 600 corpses in their retreat, and their total casualties must have been far higher. The French scoured the battlefield during the afternoon of 4 January, and killed all the wounded Chinese soldiers they could find with pistol shots to the head. Several dozen Chinese soldiers may have been despatched in this way.[20]

A number of unwounded Chinese soldiers were taken prisoner by the French at Nui Bop and subsequently interrogated for their knowledge of the Guangxi Army's order of battle. These men were released at the end of the war with small gratuities.[21]

Order of the day

On 5 January 1885 General Brière de l'Isle issued the following order of the day to commemorate the victory at Nui Bop:

Deux brillants succès pour le corps expéditionnaire ouvrent l’année 1885. Le 3 janvier, après une marche habilement dérobée aux yeux de l’ennemi, le général de Négrier tombait, à quatre heures du soir, sur un cantonnement de 6,000 réguliers et, malgré leur vive résistance, les mettait, en moins de deux heures, en pleine déroute sans que l’obscurité de nuit lui permit de poursuivre ce premier succès. Nos troupes couchaient sur les positions enlevées. Le lendemain, avant le jour, les Chinois, au nombre de 12,000, recommençaient la lutte par un vigoureux retour offensif. Repoussés, poursuivis et enfin rejetés sur Nui-Bop, ils étaient en pleine déroute avant midi. Le centre de résistance de Nui-Bop, défendu par huit forts solidement organisés, est entre nos mains, avec deux batteries Krupp, ainsi que tout le matériel de l’ennemi: tentes, vivres, munitions, armes et étendards. Les cadavres de 600 réguliers chinois tués ont été abandonnés par les fuyards. De notre côté, MM. Verdier, capitaine au 111e, Simoni, lieutenant au même corps, Larribe, sous-lieutenant d’infanterie de marine, sont blessés sans gravité. Parmi nos braves soldats, 19 tués et 63 blessés.[22]

(1885 has opened with two splendid successes for the expeditionary corps. On 3 January, after a march skillfully concealed from the enemy’s eyes, General de Négrier fell upon a cantonment of 6,000 regulars at 4 pm and would have completely routed them, despite their lively resistance, in less than two hours had not nightfall prevented him from pursuing his initial success. Our troops slept on the positions they had captured. Before dawn on the following day 12,000 Chinese made a vigorous counterattack. Repelled, pursued and finally thrown back on Nui Bop, they were in full flight before midday. Nui Bop, the centre of their resistance, defended by eight solidly organized forts, is in our hands, with two Krupp batteries and all the enemy’s material: tents, food, ammunition, weapons and standards. The bodies of 600 dead Chinese regulars were abandoned by their fleeing comrades. On our part Captain Verdier and Lieutenant Simoni of the 111th and 2nd Lieutenant Larribe of the marine infantry were lightly wounded. Losses among our brave soldiers were 19 dead and 63 wounded.)

Significance

De Nègrier's victory at Nui Bop, won at odds of just under one to ten, was regarded by his fellow-officers as the most spectacular professional triumph of his career. By clearing the Guangxi Army away from Nui Bop, de Nègrier removed a threat to the French right flank and gave the French base at Chu the air it needed for the major campaign against Lang Son. With the Western Fort at Nui Bop in French hands, the expeditionary corps was able to use the Nui Bop plain to establish the large magazines of food and ammunition that would be needed for the Lang Son expedition.

French strategy in Tonkin had been the subject of a bitter debate in the Chamber of Deputies in late December 1884. The army minister General Jean-Baptiste-Marie Campenon argued that the French should consolidate their hold on the Delta. His opponents urged an all-out offensive to throw the Chinese out of northern Tonkin. The debate culminated in Campenon's resignation and his replacement as army minister by the hawkish General Jules Lewal. On 5 January 1885, the day after de Nègrier's victory at Nui Bop, Lewal ordered Brière de l’Isle to 'capture Lang Son as soon as possible'. A month later, after concentrating his forces in the plain of Chu, Briere de l'Isle launched the Lang Son Campaign, a successful ten-day campaign to capture Lang Son.[23]

Notes

- ↑ Mahias's battalion consisted of the 25th, 29th, 34th and 36th Companies, 1st Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Tailland, Salles, Hougnon and Bourguignon). De Mibielle's Turco battalion was the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Algerian Rifle Regiment (Captains Camper, Chirouze, Polère and Valet).

Footnotes

- ↑ Harmant, 113–37; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 155–76; Lung Chang, 332; Maury, 129–32; Thomazi, Conquête, 243; Histoire militaire, 104–5

- ↑ Harmant, 91–112; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 149–55

- ↑ Lung Chang, 332

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 154

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 155

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 158

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 158–9

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 159

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 160

- ↑ Lecomte, 160

- 1 2 3 Lecomte, Lang-Son, 161

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 162

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 163

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 164

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 164–5

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 165 and 168

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 166–7

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 169–71

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 172

- ↑ Dreyfus, 85

- ↑ Lecomte, La vie militaire, 79–86

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 175

- ↑ Lung Chang, 332; Thomazi, Conquête, 242–3

References

- Dreyfus, G., Lettres du Tonkin, 1884–1886 (Paris, 2001)

- Harmant, J., La verité sur la retraite de Lang-Son (Paris, 1892)

- Lecomte, J., Lang-Son: combats, retraite et négociations (Paris, 1895)

- Lecomte, J., La vie militaire au Tonkin (Paris, 1893)

- Dick de Lonlay, Les combats du général de Négrier au Tonkin (Paris, Garnier frères, 1886)

- Maury, A., Mes campagnes au Tong-King (Lyons, undated)

- Lung Chang [龍章], Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng [越南與中法戰爭, Vietnam and the Sino-French War] (Taipei, 1993)

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l'Indochine français (Hanoi, 1931)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)