Atchison, Kansas

| Atchison, Kansas | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Commercial Street in downtown Atchison (2006) | |

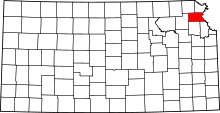

Location within Atchison County and Kansas | |

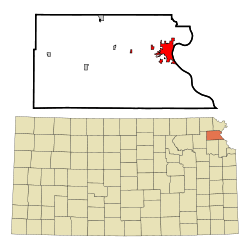

KDOT map of Atchison County (legend) | |

| Coordinates: 39°33′45″N 95°7′42″W / 39.56250°N 95.12833°WCoordinates: 39°33′45″N 95°7′42″W / 39.56250°N 95.12833°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kansas |

| County | Atchison |

| Founded | 1854 |

| Incorporated | 1855 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Jack Bower |

| • City Manager | Trey Cocking |

| Area[2] | |

| • Total | 8.29 sq mi (21.47 km2) |

| • Land | 7.83 sq mi (20.28 km2) |

| • Water | 1.19 sq mi (0.46 km2) |

| Elevation[1] | 814 ft (248 m) |

| Population (2010)[3] | |

| • Total | 11,021 |

| • Estimate (2014)[4] | 10,771 |

| • Density | 1,300/sq mi (510/km2) |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 66002 [5] |

| Area code | 913 |

| FIPS code | 20-02900 [1] |

| GNIS ID | 473516 [1] |

| Website |

CityOfAtchison |

Atchison is a city and county seat of Atchison County, Kansas, United States, and situated along the Missouri River. As of the 2010 census, its population was 11,021.[6]

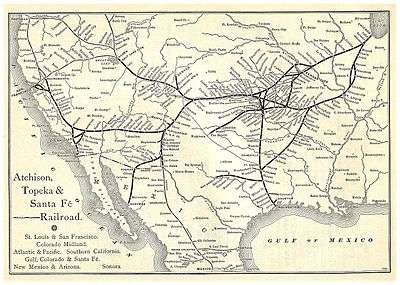

The city is named in honor of David Rice Atchison, United States senator from Missouri, and was the original eastern terminus of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway.

Atchison was the birthplace of aviator Amelia Earhart, and the Amelia Earhart Festival is held annually in July. Atchison is also home of Benedictine College, a Catholic liberal-arts college.

History

Founding

Atchison was founded in 1854 and named in honor of Senator David Rice Atchison, who, when Kansas was opened for settlement, interested some of his friends in the scheme of forming a city in the new territory.[7] Senator Atchison was interested in ensuring that the population of the new Kansas Territory would be majority pro-slavery, as he had been a prominent promoter of both slavery and the idea of popular sovereignty over the issue in the new lands. However, it seems that all were not agreed upon the location he had selected, and on July 20, 1854, Dr. John H. Stringfellow, Ira Norris, Leonidas Oldham, James B. Martin and Neal Owens left Platte City, Missouri, to decide definitely upon a site. They found a site that was the natural outlet of a remarkably rich agricultural region just open to settlement. George M. Million and Samuel Dickson had staked claims near the river; Dr. Stringfellow staked a tract north of Million's. Million sold his claim for $1,000—an exorbitant price. Eighteen persons were present when the town company was formally organized by electing Peter T. Abell, president; James Burns, treasurer; and Dr. Stringfellow, secretary. The site was divided into 100 shares by the company, of which each member retained five shares, the remainder being reserved for common benefit of all. By September 20, 1854, Henry Kuhn had surveyed the 480 acres (1.9 km²) and made a plat, and the next day was fixed for the sale of lots, an event of great importance as it had become understood that Senator Atchison would make a speech upon the political question of the day, hence the sale would be of political as well as business significance. At his meeting on the 21st, two public institutions of vital interest to a new community were planned for—a hotel and a newspaper. Each share of stock in the town company was assessed $25, the proceeds to be used to build the National Hotel, which was completed in the spring of 1855, and $400 was donated to Dr. Stringfellow and Robert S. Kelley to erect a printing office.

The Squatter Sovereign, a paper with strong pro-slavery sentiments, was first issued on February 3, 1855. It had formerly been published at Liberty, Missouri, under the name of the Democratic Platform. In the spring of 1857 it was purchased by Samuel C. Pomeroy, Robert McBratney and F.G. Adams, who changed its policy and published it as a free-state paper until the fall of the same year, when Pomeroy became the sole owner.[8]

The first post office in Atchison was established April 10, 1855, with Kelley as postmaster. It was opened in a small building in the block later occupied by the Otis house. In July 1883, the free-delivery system was inaugurated.

For years there had been considerable trade up and down the Missouri River, which had naturally centered at Leavenworth, but in June 1855, several overland freighters, such as Livingston, Kinkead & Co., and Hooper & Williams were induced to select Atchison as their outfitting point and formed the basis that established Atchison as a commercial center. Early merchants to establish businesses in the new town were George Challis, Burns Bros., Stephen Johnston and Samuel Dickson..

On August 30, 1855, Atchison was incorporated.[9] Dr. Stringfellow had North Atchison surveyed and platted in the fall of 1857. This started a fever of additions. In February 1858, West Atchison was laid out by John Roberts, and in May Samuel Dickson had his property surveyed as South Atchison. Still another addition was made by John Challis.

In 1858 the anti-slavery forces took control of the city. On February 12, 1858, the legislature issued a charter to the city of Atchison, which was approved by the people on March 2 at a special election. The first city officers were elected at a second special election on March 13, 1858, and Republican Samuel C. Pomeroy was elected mayor. The German element, largely Catholic, opposed the Sunday closing laws of the new city government, but a satisfactory compromise was reached that allowed the sale of beer on Sundays after church services.[10]

Early development

The first schools in the town were private, including parochial schools operated by the Germans. One of the first English schools was opened in 1857 by Lizzie Bay. The first school district was established in October 1858, and a month later the Atchison free high school was opened at the corner of Atchison and Commercial streets.

Civil War

At the outbreak of the American Civil War there were three militia companies organized in Atchison, whose members enlisted in the Kansas regiments. They were known as Companies A, C and “At All Hazards”. Early in September 1861, a home guard was organized in the town to protect it in case of invasion from Missouri, and on the 15th of the month another company was raised, which was subsequently mustered into a state regiment. In 1863 the city of Atchison raised $4,000 to assist the soldiers from the county and after the Lawrence Massacre a like sum was subscribed to assist the stricken people of that city. Citizens of the town also joined the vigilance committees that so materially aided the civil authorities in suppressing raiding and the lawless bands of thieves that infested the border counties.

During the war, Atchison was also the headquarters of numerous bands of jayhawkers including the notorious Charles Metz, who was known as Cleveland. Metz, a former prisoner at the Missouri State Penitentiary, selected Atchison as his headquarters for raids into Missouri and was accepted with open arms by the people of the town.[11] During his period of operations, he stole hundreds of horses from Missouri farmers and sold them in Kansas. He robbed any suspected southern sympathizer and threatened several leading citizens with murder and robbery if they remained in town. He even had the audacity to run off the first president of Atchison, P.T. Abell, who was forced into exile until after the Civil War concluded. He defied all authorities who attempted to rein in his excesses, but was finally shot and killed at some point in 1862. He is buried in St. Joseph, Missouri.

Industrialization

In the late 1850s, plans were underway to connect California to the rest of the country by rail. The logical location for a western terminus was in or around San Francisco, California, but an eastern terminus had yet to be chosen. Atchison was in fierce competition to be selected as the terminus, and in order to bolster its position, a rail line was constructed from St. Joseph, Missouri to Atchison between 1857 and 1859, funded in large part by $150,000 raised by the citizens of Atchison and connected to the Hannibal & St. Joseph R.R. at its eastern end.[12] The Atchison and Topeka Railroad was founded in 1859 with Atchison as its eastern terminus and the intention of connecting Kansas to the southwest by rail. Although construction was delayed by the Civil War, a land grant similar to the one given the Union Pacific to construct the first transcontinental railroad was made by the federal government to Kansas in 1863, which was transferred to the newly reformed Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad (AT&SF). Finally, in 1868, construction was begun on the line in Topeka, but was aimed west and south towards the Colorado border. The connection between Atchison and Topeka, a distance of less than 50 miles, would not be completed until May, 1872.

The city tried to become a major railroad center, but was surpassed by Kansas City and Omaha, due to the former's greater industrial capability and connections to Texas and the latter's connection to Chicago, rather than St. Louis. Furthermore, Atchison boosters were unable to unite on a single project, instead scattering their efforts to the southwest, west and northwest, none of which proved successful. A proposed "Atchison and Pike's Peak" line was eventually taken over by the Union Pacific, while a speculative Atchison-Nebraska connector was eventually finished and taken over by other investors. Bickering delayed the building of bridges, stockyards, elevators, warehouses and railroad yards, revealing the disharmony that plagued Atchison's entrepreneurs.[13]

However, with the completion of the connector to St. Joseph, which later became part of the Missouri Pacific, and the final connection to the growing AT&SF system, industrialization reached Atchison. Grain elevators, flour mills, and a flax mill were all erected in Atchison in the late 1860s and early 1870s. Several prominent businessmen in town lured Captain John Seaton, who operated a foundry in Alton, Illinois, to town to improve the Atchison Foundry and Machine Works in 1872. It soon began turning out decorative wrought iron fences, spiral staircases, and hitching posts for horses.[14] The foundry expanded quickly, as Seaton transported his entire Alton operation to Atchison to establish the Seaton Foundry. It employed over 200 men and had a payroll of more than $14,000 per month in 1872. Expanding rapidly in the coming years, it was known as Seaton Lea for most of the 1870s, becoming the Atchison Foundry and Machine Works in 1880. A branch location was constructed in Lincoln, Nebraska in 1881, but closed in 1887. In 1905, the Locomotive Finished Materials Company was established by Harry E. Muchnic, formerly of the AT&SF railroad, which produced finished materials for the construction of railroad locomotives in close conjunction with Seaton's foundry. The companies eventually merged in 1914 after the 1912 death of John Seaton.

After his arrival in 1872, John Seaton became one of the leading citizens of Atchison. Besides establishing the foundry which became the center of the town's industry, he also owned the local theater, served on the school board, was elected to the Kansas Legislature in 1889, served on the Kansas Penitentiary Board, and was nominated for Governor of Kansas. He died on January 12, 1912.

In 1914, Harry Muchnic invented a revolutionary diesel locomotive piston ring. In 1924 the John Seaton Foundry built an electric arc melting furnace for efficient smelting. In 1924 Atchison began the transition from iron to steel which paved the transition from steam locomotives to diesel locomotives. The first steel locomotive truck assembly was designed, cast, and assembled in 1934. In 1938 LFM was making 18 locomotive assemblies every day for General Motors-Electric Motive Division (EMD) and continued to be a key supplier of components to EMD.

In 1958 Rockwell purchased the LFM Steel Foundry to make locomotive trucks for EMD and GM (Progress Rail). Rockwell's Transit Truck Design Group was established in 1960. Rockwell Manufacturing and Rockwell International were the owners from 1956-1993 and they renamed the LFM to Atchison Casting Corporation (ACC) in 1991. Atchison Casting became a publicly held corporation in 1994. ACC bought the Old Canadian Steel Foundry in Montreal, Canada from Hawker Siddeley in 1995. The foundry has primarily become a producer of rail transport components, including commuter rail truck frames for commuter rail systems in San Francisco, Chicago, Atlanta, and Washington, D.C. It has also undergone various mergers, reorganizations, and renamings, most recently after it was purchased by Bradken, a global manufacturing company headquartered in Australia.

Geography

Atchison is located at 39°33′45″N 95°7′42″W / 39.56250°N 95.12833°W (39.562499, -95.128257).[15] The city is along the western bank of the Missouri River which also marks the Kansas-Missouri state line. Located at the junction of U.S. Route 59 and U.S. Route 73, it is 21 miles (34 km) southwest of St. Joseph, Missouri, along US-59 and 25 miles (40 km) northwest of Leavenworth, Kansas, along US-73. The section of US-73 between Atchison and Leavenworth is part of the Glacial Hills Scenic Byway which follows K-7 northward from Atchison.[16]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.29 square miles (21.47 km2), of which, 7.83 square miles (20.28 km2) is land and 0.46 square miles (1.19 km2) is water.[2]

Climate

Atchison has a humid-continental climate with variable winters and hot, humid summers. Over the course of a year, temperatures range from an average low of nearly 15 °F (−9 °C) in January to an average high of nearly 90 °F (32 °C) in July. The maximum temperature reaches 90 °F (32 °C) an average of 38 days per year and reaches 100 °F (38 °C) an average of 3 days per year. The minimum temperature falls below the freezing point (32 °F) an average of 106 days per year. Typically the first fall freeze occurs between the second week of October and the first week of November, and the last spring freeze occurs between the end of March and the third week of April.

The area receives nearly 38 inches (970 mm) of precipitation during an average year with the largest share being received in May, June, and July—with a combined 29 days of measurable precipitation. During a typical year the total amount of precipitation may be anywhere from 25 to 52 inches (1,300 mm). There are on average 96 days of measurable precipitation per year. Winter snowfall averages almost 23 inches, but the median is less than 16 inches (410 mm). Measurable snowfall occurs an average of 13 days per year with at least an inch of snow being received on eight of those days. Snow depth of at least an inch occurs an average of 27 days per year.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperatures (°F) | |||||||||||||

| Mean high | 35.5 | 42.4 | 54.2 | 65.6 | 75.5 | 84.5 | 89.4 | 87.6 | 79.9 | 68.4 | 52.0 | 39.4 | 64.5 |

| Mean low | 15.9 | 21.2 | 31.2 | 42.2 | 54.1 | 63.1 | 68.0 | 64.7 | 56.1 | 45.3 | 31.6 | 20.9 | 42.9 |

| Highest recorded | 72 (1989) |

80 (1972) |

89 (1946) |

92 (1989) |

96 (1956) |

105 (1980) |

109 (1980) |

109 (1984) |

108 (1947) |

98 (1939) |

84 (1980) |

74 (1939) |

109 (1984) |

| Lowest recorded | −19 (1947) |

−16 (1979) |

−10 (1978) |

11 (1975) |

28 (1944) |

42 (1945) |

47 (1968) |

44 (1950) |

30 (1942) |

19 (1942) |

−2 (1976) |

−21 (1989) |

−21 (1989) |

| Precipitation (inches) | |||||||||||||

| Median | 1.09 | 0.97 | 1.91 | 2.98 | 4.27 | 3.87 | 3.81 | 3.33 | 3.28 | 2.96 | 2.31 | 1.18 | 36.08 |

| Mean number of days | 6.1 | 5.9 | 8.4 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 6.0 | 95.5 |

| Highest monthly | 2.73 (1993) |

2.96 (1997) |

8.34 (1973) |

7.07 (1999) |

12.68 (1982) |

10.85 (1996) |

16.51 (1992) |

10.59 (1977) |

12.56 (1977) |

7.44 (1977) |

5.88 (1975) |

3.75 (1980) |

{{{14}}} |

| Snowfall (inches) | |||||||||||||

| Median | 6.2 | 5.3 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 15.7 |

| Mean number of days | 4.0 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 12.7 |

| Highest monthly | 29.4 (1979) |

20.0 (1978) |

16.2 (1976) |

7.0 (1975) |

0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 (1996) |

9.1 (1975) |

17.5 (1983) |

{{{14}}} |

| Notes: Temperatures are in degrees Fahrenheit. Precipitation includes rain and melted snow or sleet in inches; median values are provided for precipitation and snowfall because mean averages may be misleading. Mean and median values are for the 30-year period 1971–2000; temperature extremes are for the station's period of record (1939–2001). The station is located in Atchison at 39°34′N 95°7′W, elevation 945 feet (288 m). | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 2,616 | — | |

| 1870 | 7,054 | 169.6% | |

| 1880 | 15,105 | 114.1% | |

| 1890 | 13,963 | −7.6% | |

| 1900 | 15,722 | 12.6% | |

| 1910 | 16,429 | 4.5% | |

| 1920 | 12,630 | −23.1% | |

| 1930 | 13,024 | 3.1% | |

| 1940 | 12,648 | −2.9% | |

| 1950 | 12,792 | 1.1% | |

| 1960 | 12,529 | −2.1% | |

| 1970 | 12,565 | 0.3% | |

| 1980 | 11,407 | −9.2% | |

| 1990 | 10,656 | −6.6% | |

| 2000 | 10,232 | −4.0% | |

| 2010 | 11,021 | 7.7% | |

| Est. 2015 | 10,712 | [17] | −2.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 11,021 people, 3,933 households, and 2,447 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,407.5 inhabitants per square mile (543.4/km2). There were 4,442 housing units at an average density of 567.3 per square mile (219.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 87.9% White, 7.2% African American, 0.6% Native American, 0.5% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.7% from other races, and 3.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.7% of the population.

There were 3,933 households of which 33.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.0% were married couples living together, 13.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 37.8% were non-families. 31.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 3.08.

The median age in the city was 31.6 years. 23.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 18.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 20.9% were from 25 to 44; 22.2% were from 45 to 64; and 14.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.2% male and 52.8% female.

2000 census

As of the U.S. Census in 2000,[19] there were 10,232 people, 3,863 households, and 2,437 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,498.2 people per square mile (578.4/km²). There were 4,220 housing units at an average density of 617.9 per square mile (238.6/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 88.56% White, 7.80% Black or African American, 0.51% Native American, 0.41% Asian, 0.09% Pacific Islander, 0.65% from other races, and 1.99% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.58% of the population.

There were 3,863 households out of which 30.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.8% were married couples living together, 12.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.9% were non-families. 32.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 3.00.

In the city the population was spread out with 25.7% under the age of 18, 13.8% from 18 to 24, 23.5% from 25 to 44, 19.5% from 45 to 64, and 17.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females there were 88.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,109, and the median income for a family was $37,100. Males had a median income of $31,027 versus $20,262 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,441. About 9.5% of families and 17.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.4% of those under age 18 and 22.0% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Atchison Public Schools school district (USD 409), with three schools, serves more than 1,600 students.[20] In 1997 the Atchison Public Schools closed six of its neighborhood school buildings to open one large elementary school. Although schools had been desegregated for more than 50 years, this move ensured more diversity and equality of education by uniting different segments of the city's children into one school. A few of the old neighborhood schools still stand - one, known as Lincoln school at 810 Division Street was historically a segregated school for black children. Many entities have attempted to restore Lincoln School, which is on the Kansas State Register of Historic Places.[21]

- Atchison Elementary School, grades K–5

- Atchison Middle School, grades 6–8

- Atchison High School, grades 9–12[22]

- Atchison Alternative School, grades 6-12

Other private schools in the city include:

- Maur Hill Mount Academy

- Trinity Lutheran School

- St. Benedict Catholic School (was renamed from Atchison Catholic Elementary School in 2013)

Colleges and universities

- Benedictine College

- Highland Community College

- Northeast Kansas Technical College

Notable people

- Willis J. Bailey, U.S. Representative and 16th governor of the state.

- Laura M. Cobb, United States Navy nurse during World War II.

- Amelia Earhart, aviator.

- Rory Lee Feek, songwriter and half of county duo Joey and Rory.

- George W. Glick, Ninth governor of the state.

- Sheffield Ingalls, former Lieutenant governor of Kansas.

- John James Ingalls, Former state and U.S. senator who coined the state motto, Ad Astra per Aspera.

- James Edmund Jeffries, politician.

- Ernie Jennings, football player.

- Oscar Johnson, baseball player with Kansas City Monarchs.

- Victor Linley, Wisconsin State Senator.

- John Alexander Martin, Tenth governor of the state.

- Jesse Stone, American rhythm and blues musician and songwriter. Developed the basic rock 'n' roll sound.

Points of interest

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Atchison County, Kansas

- Amelia Earhart Birthplace Museum

- Santa Fe Depot Rail Museum[23]

- International Forest of Friendship, arboretum

See also

- Atchison Storage Facility

- Central Branch Union Pacific Railroad

- Lewis and Clark Trail

- SS Atchison Victory

References

- 1 2 3 4 Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) details for Atchison, Kansas; United States Geological Survey (USGS); October 13, 1978.

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-01-24. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ United States Postal Service (2012). "USPS - Look Up a ZIP Code". Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ↑ "2010 City Population and Housing Occupancy Status". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ↑ Frank W. Blackmar, ed. (1912). "Atchison". Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc ... I. Chicago: Standard Pub Co. pp. 108–111. The primary source for this history.

- ↑ Frank W. Blackmar, ed. (1912). "Newspapers". Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc ... II. Chicago: Standard Pub Co. pp. 358–367.

- ↑ History of the State of Kansas: Containing a Full Account of Its Growth from an Uninhabited Territory to a Wealthy and Important State. A. T. Andreas. 1883. p. 375.

- ↑ Turk, 1979, p 154

- ↑ Ingalls, Sheffield (1916). History of Atchison County, Kansas. Standard Publishing Company.

- ↑ Cutler, William. "History of the State of Kansas". Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ George L. Anderson, "Atchison, 1865–1886, Divided and Uncertain," Kansas Historical Quarterly, 1969, Vol. 35 Issue 1, pp 30–45

- ↑ Cutler, William. "History of the State of Kansas". Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Glacial Hills Scenic Byway". Kansas Scenic Byways. Archived from the original on 2006-06-16. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Atchison Public Schools schools". GreatSchools.net. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- ↑ "Kansas Historic Resources Inventory 005-0260-00903 Lincoln School, 810 Division St. Atchison.". kansasgis.org/. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- ↑

- ↑ "Atchison Santa Fe Depot Rail Museum". freewebs.com. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

Further reading

- Turk, Eleanor L. "The Germans of Atchison, 1854-1859: Development of an Ethnic Community." Kansas History 2 (Autumn 1979): 146–156. online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atchison, Kansas. |

- City of Atchison

- Atchison Area Chamber of Commerce

- Atchison - Directory of Public Officials

- The Atchison Globe, local newspaper

- USD 409, local school district

- Atchison community

- Atchison City Map, KDOT