Azerbaijani traditional clothing

| Part of a series on |

| Azerbaijanis |

|---|

| Culture |

| Traditional areas of settlement |

| Diaspora |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Persecution |

|

Traditional Azerbaijani dress (Azerbaijani: Azərbaycan Milli geyimləri) has developed as a result of long processes of material and religious culture of Azerbaijani people. It is closely connected to its history and reflects its national specification.[1]

Ethnographic, historic and artistic features of the national creativity, which were also used in creation of determined forms of it, are reflected on costumes. Azerbaijani arts reminds about itself also in ornaments of costume with artistic embroideries, in weaving and knitting.

In the 17th century, the territory of modern Azerbaijan was considered the main sericulture oblasts of the Near East and Shirvan was the main region of sericulture. Silks were produced in Shamakhi, Basqal, Ganja, Shaki, Shusha and in other regions. Fine textiles, silk head kerchiefs for women with ornaments of amazing beauty and others were produced in these cities.

Style of clothes reflected marital status and age of its owner. For example, costume of a girl and a married woman were differed. Young women wore more colorful and beautiful dresses.

From the 20th centuries national costumes in Azerbaijan are worn only in villages. Almost all national dances are performed in national costumes.

Men's wear

Male national costume actually was single in all zones of Azerbaijan. Class distinction the owner was reflected on male costumes.

Outerwear

National outerwear for men consisted of “ust koyney” (shirt) or chepken, arkhalig, gabi and chukha (humeral wear).

- Arkhalig – was single-breasted or two-breasted. It was sewed of silk, cashmere, cloth, satin and other textiles.

- Gaba – male humeral outerwear, which was sewed of tirme.

- Chukha - male humeral outerwear, which was detachable on the waist, with layers and gathers. It was sewed of cloth, tirme and homespun textile.

- Kurk – fur coat made of lamb fur, without fastener, with collar, decorated with embroidery.

One of the Russian ethnographers writes about Azerbaijani male costume:

|

Underwear consists of straight and short shirts of coarse calico, white and mostly dark blue colors with underpants of this very material, which are fastened with tapes on the waist; in winter they are worn over woolen large pants, which are also fastened with tapes. Over a shirt is worn arkhalig made of cotton. Arkhalig is such as Russian man’s long tight-fitting coat with short waist and short skirt with gathers on the belt; it is always fastened tightly or in the midst or aside of the chest. Chukha is worn over arkhalig with short waist and with a skirt with length of below knees, but the head is covered with small conic shaped hat made of lamb fur, throughout the year. Short woolen socks are worn to feet. |

Headdresses

Papaq was considered a symbol of fortitude, honor and dignity of men in Azerbaijan and losing it was considered as a disgrace. Larceny of papaq was considered as a hostile action against its owner. It was possible to outrage a man and all his generation by knocking down papaq from his head. Social dignity of papaq’s owner could be determined by its form. Men never took their papaqs off (even during dinner), except voodoo before salat. Appearance in public places without headdress was considered an indecent action.[2]

- Papaqs made of lamb fur or karakul was the main headwear for men. They had different forms and local names. According to E.Torchinskaya, there have kept 4 types of Azerbaijani papaqs in the State Hermitage Museum of Saint Petersburg:

- Yappa papaq (or “qara papaq” – “black papaq”) – was widely spread in Karabakh and was covered with textile. They were differed by color – “gizil papaq” (golden) and gumush papaq (silver).

- Motal papaq (or “choban papagi” – “shepherd’s papaq”) – was made of longhaired lamb fur and was in shape of cone. Motal papaq was generally worn by poor strata of the society.

- Shish papaq (or “bey papagi” – “bey’s papaq”) – was cone shaped or sharp ended. According to the name of material, which it was sewed of, they had a general name – Bukhara papaq, a fur which was brought from Bukhara. It was worn only by representatives of beys’ estate and also prosperous people. Such kind of papaqs were typical for city aristocracy.

- Dagga (tagga) papaq – was spread in Nukhinsky Uyezd. Its top was sewed of velvet.

- Bashlyk – consisted of hood and long, round ends, wound round neck. In winter was worn a bashlyg made of cloth and wool. Bashlygs made of camel wool, the lining of which was sewed of colorful silk, because when bashlyk’s ears were thrown over shoulders the lining was visible, were especially valued in Shirvan . Generally bashlyk was accompanied by yapinji.

- Arakhchin – was worn under other headdresses (papaq, chalma for women). It was a typical traditional headwear of Azerbaijanis and was widely spread even in the Middle Ages.

- Emmame – (type of chalma) was existed among religious people (Mullahs, Sayyids, Sheikhs and others).

Shoes

“Jorabs” - woolen socks were widely spread in Azerbaijan. City residents wore leather shoes with folded toes of slip-ons. Boots were spread among aristocrats. “Charigs” – everyday shoes made of leather or rawhide were worn by villagers.

Women's wear

National female costume of Azerbaijanis consists of outwear and underwear. It includes suck-formed shawl – “chadra” and a veil – “rubend”, which was worn by women while going outdoors. Outwear was sewed of bright and colorful textiles, the quality of which depended on income of the family. The clothing also included variety of different jewelries. Golden and silver beads, buttons, stylized as a big seeds of hordeum, coins, delicate pendants and necklaces. Unlike elders young women wore more bright clothes with bright flowers.[3]

In the 19th century, Ivan Ivanovich Chopin described clothes of Azerbaijani women in Armenian Oblast (calling them “tatars”) is such way:

|

Dances of Tatar women are incomparably pleasant and their dresses promote originality of them: this clothing consists of a brocaded knitted jacket, which is fastened at the waist and a red silk chemise with large slit at the front, which is fastened at the neck, and reveals bronze colors in every motion which are tattooed in different ornaments; wide trousers substitute for a skirt and their width can argue with volume of a skirt which is the more stylish than the European purists. Tatar women wear decorated woolen socks with bright colors instead of stockings; thick black curly hair, thrown over the shoulders, completes the clothing and substitutes for any sort of more fanciful headdress. |

Outwear

Outwear consists of a shirt with wide sleeves and wide trousers to the ankle and bell-shaped shirts of the same length. Women also wore a knitted shirt with long sleeves (arkhalig, kuladja) tightly fitting across the back and chest, which had a wide slit at the front. At the waist it was tightly belted, but below it was parted by gatherings. A quilted sleeveless jacket was worn in cold weather. Outerwear could be a cloak that was longer than the shirt. Women’s shirts in Gazakh uyezd were long with slits on each side.[4]

Women of Karabakh wore chepken (chafken) that was tight-fitting to the waist and with long hidden sleeves.

Wide skirts and also tight and wide pants existed. Short, to the knee, shirts were worn in Nakhchivan. In Shusha, Shamakhi and other districts shirts were longer.

Long kulajs were worn only by rich women in Nakhchivan and Ganja.

Headdresses

It consisted of leather in form of suck or caps of different forms. Over it were worn several headscarves. Women hid their hair into a special suck – chutga. Head was covered with a cylindrical pillbox cap. More often it was made of velvet. Over it was tied a chalma and several headscarves kalaghai.

Shoes

On feet were worn socks – jorab. Shoes were slip-ons as for men.

Gallery

-

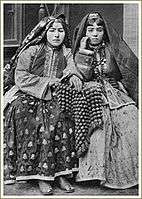

Azerbaijani girl from Shusha. Photographer Konstantin Zanis. 1898.

-

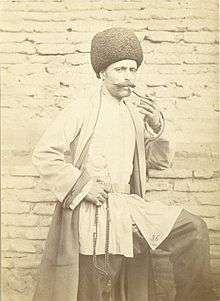

Young Azerbaijani from Shamakhi. 1883.

-

Azerbaijani from Baku. 1883.

-

Baku Azerbaijanis in neat costumes . Photographer Luarsabov. 1881.

-

Khurshidbanu Natavan with her son Mehdigulu Khan Vafa and daughter Khanbike.

-

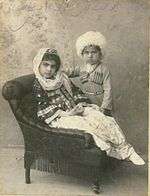

Musa Naghiyev's son and daughter(Son-in chukha, daughter-in Chepken).

-

Sara Ashurbeyli with sisters.

-

Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli with his family.

In philately

-

The USSR stamp, 1963.

-

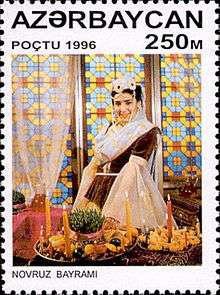

Azerbaijani stamp, 1996.

-

Azerbaijani stamp, 1997.

-

Azerbaijani stamp, 1997.

References

- ↑ "История азербайджанского национального костюма". azeri.ru. 2010-02-19.

- ↑ "Азербайджанский национальный костюм". azeri.ru.

- ↑ "AZERBAIJAN NATIONAL COSTUMES".

- ↑ "MİLLİ GEYİMLƏR".