Batavia, Dutch East Indies

Batavia was the name of the capital city of the Dutch East Indies and corresponds to the present-day city of Jakarta. Just as modern Jakarta may refer to either the city itself or to the larger area of the city, with its geographic surroundings, which taken together is one of the provinces of Indonesia, Batavia can refer to the city proper as it existed then, with its various increases over time in urbanized acreage, or can refer to the surrounding hinterland.

The establishment of Batavia at the site of the razed city of Jayakarta by the Dutch in 1619 led to the Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following World War II. Batavia became the center of the Dutch East India Company's trading network in Asia.[1]:10 Monopolies on nutmeg, black pepper, cloves and cinnamon were augmented by non-indigenous cash crops like coffee, tea, cacao, tobacco, rubber, sugar and opium. To safeguard their commercial interests, the company and the colonial administration, which replaced it in 1799, progressively absorbed surrounding territory.[1]:10

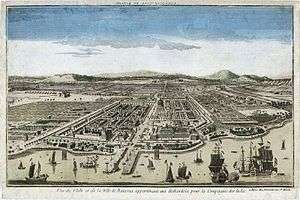

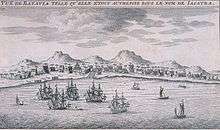

Batavia lies on the north coast of Java, in a sheltered bay, over a flat land consisting of marshland and hills, and crisscrossed with canals. The city consisted of two centers: Oud Batavia or Benedenstad ("Lower City"), the oldest, the lowest and the most unhealthy part of the city, and Bovenstad ("Upper City"), the relatively newer city located on the higher ground to the south.

Batavia was a colonial city for about 320 years until 1942 when the Dutch East Indies fell under Japanese occupation during World War II. During the Japanese occupation and again after Indonesian nationalists declared independence on August 17, 1945, the city was renamed Jakarta.[2] After the war, the Dutch name "Batavia" remained internationally recognized until full Indonesian independence was achieved on December 27, 1949 and Jakarta was officially proclaimed the national capital of Indonesia.[2]

Dutch East India Company (1610–1800)

Arrival

In 1595, merchants from Amsterdam embarked upon an expedition to the East Indies archipelago. Under the command of Cornelis de Houtman, the expedition reached Bantam, capital of the Sultanate of Banten, and Jayakarta in 1596 to trade in spices.

In 1602, the English East India Company's first voyage, commanded by Sir James Lancaster, arrived in Aceh and sailed on to Bantam. There he was allowed to build a trading post that became the center of English trade in Indonesia until 1682.[3]:29

In 1602, the Dutch government granted a monopoly on Asian trade to the Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC); literally[4] United East Indian Company).[5]:26[6]:384–385 In 1603, the first permanent Dutch trading post in Indonesia was established in Bantam, West Java. In 1610, Prince Jayawikarta granted permission to Dutch merchants to build a wooden godown and houses on the east bank of the Ciliwung River, opposite to Jayakarta. This outpost was established in 1611.[7]:29

As Dutch power increased, Jayawikarta allowed the British to erect houses on the west bank of the Ciliwung River, as well as a fort close to his customs office post, to keep the forces balanced.

In December 1618, the tense relationship between Prince Jayawikarta and the Dutch escalated, and Jayawikarta's soldiers besieged the Dutch fortress, containing the godowns Nassau and Mauritius. A British fleet of 15 ships arrived under the leadership of Sir Thomas Dale, an English naval commander and former governor of the Colony of Virginia. After a sea battle, the newly appointed Dutch governor, Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1618), escaped to the Moluccas to seek support (The Dutch had already overtaken the first of the Portuguese forts there in 1605). Meanwhile, the commander of the Dutch garrison, Pieter van den Broecke, along with five other men, was arrested during negotiations, as Jayawikarta believed that he had been deceived by the Dutch. Later, Jayawikarta and the British entered into a friendship agreement.

The Dutch army was on the verge of surrendering to the British when, in 1619, Banten sent a group of soldiers to summon Prince Jayawikarta. Jayawikarta's friendship agreement with the British was without prior approval from the Bantenese authorities. The conflict between Banten and Prince Jayawikarta, as well as the tense relationship between Banten and the British, presented a new opportunity for the Dutch.

Coen returned from the Moluccas with reinforcements on 28 May 1619[8] and razed Jayakarta to the ground on 30 May 1619,[9]:35 thereby expelling its population.[10]:50 Only the Padrão of Sunda Kelapa remained. Prince Jayawikarta retreated to Tanara, the eventual place of his death, in the interior of Banten. The Dutch established a closer relationship with Banten and assumed control of the port, which over time became the Dutch center of power in the region.

Establishment of Batavia

The area that became Batavia came under Dutch control in 1619, initially as an expansion the original Dutch fort along with new building on the ruined area that had been Jayakarta. The official naming ceremony was on January 18, 1621.[11] It was named after the Germanic tribe of the Batavi, as at the time of it was believed that the tribe's members were the ancestors of the Dutch people. Jayakarta was then called "Batavia" for more than 300 years.

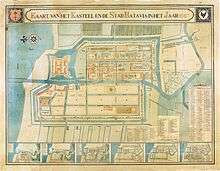

On 2 July 1619, Coen decided to expand the original fort into a larger fortress. Coen sent the draft of the Kasteel van Batavia to the Netherlands on 7 October 1619. This new castle was much larger than the previous castle, with two northern bastions protecting the castle from attack from the sea.[12] The Dutch fortress garrison included hired soldiers from Japan, Germany, Scotland, Denmark and Belgium. The godowns Nassau and Mauritius were expanded with the erection of a new fort extension to the east on March 12, 1619, overseen by Commander Van Raay.[11] Coen wished to name the new settlement "Nieuw-Hoorn" (after his birthplace, Hoorn), but was prevented from doing so by the board of the East India Company, the Heeren XVII.[11] Batavia became the new name for the fort and settlement.

Over time, there were three governmental administrations within the Batavia region.[13]:7 The initial authority, (Dutch: Hoge Regering; High Government), was established in 1609.[13]:7 This became the colonial government, consisting of the Governor-General and the Council of the Indies.[13]:7 The urban or civil administration of the city of Batavia, (Dutch: College van Schepenen; Council of Aldermen), was formed in 1620.[13]:9 On 24 June 1620 two Company officials and three free citizens or burghers were appointed to the first College van Schepenen College of Aldermen.[14] The local rural administration, (Dutch: College van Heemraden; District Council), was formed in 1664 but became fully functional in 1682.[13]:10

Batavia was founded as a trade and administrative center of the Dutch East India Company; it was never intended to be a settlement for the Dutch people. Coen founded Batavia as a trading company, whereby a city's inhabitants would take care of the production and supply of food. As a result, there was no migration of Dutch families and, instead, a mixed society was formed. As the VOC preferred to maintain complete control over its business, a large number of slaves was employed. Batavia became an unattractive location for people who wanted to establish their own businesses.

The Javanese people were prohibited from settling in Batavia from the time of its foundation in 1619,[15]:194 as the Dutch feared an insurrection. Coen asked Willem Ysbrandtszoon Bontekoe, a skipper for the Dutch East India Company, to bring 1000 Chinese people to Batavia from Macao, but only a small segment of the 1000 survived the trip. In 1621, another attempt was initiated and 15,000 people were deported from the Banda Islands to Batavia, but only 600 survived the trip.

Expansion east of the Ciliwung

From the beginning of its establishment, Batavia was planned following a well-defined layout.[16] In 1619, three trenches were dug to the east of the Ciliwung river, forming the first Dutch-made canals of Batavia. These canals were perpendicular to the Ciliwung, and were named from south to north: Leeuwengracht (usually written as Leeuwinnegracht, present Jalan Kali Besar Timur 3 or Jalan Kunir), Groenegracht (present Jalan Kali Besar Timur 1), and Steenhouwersgracht (later Amsterdamschegracht, present Jalan Nelayan Timur).[17] The Castle area starts to the north of Steenhouwersgracht, which began with a field just to the north of Steenhouwersgracht.[16] A town's market (a fish market) was established on the field.[16][17] The establishment of the three canals made way for the expansion of Batavia on the east side of the Ciliwung. The first church and town hall were built c.1622 on the east bank of the river, the exact point of this first building of the church-town hall of Batavia is at 6°07′56″S 106°48′42″E / 6.132212°S 106.811779°E.[16] This was replaced in the 1630s.

Around 1627, the three canals were interconnected perpendicularly by a coconut-tree-lined canal known as Tijgersgracht (present Jalan Pos Kota - Jalan Lada). A contemporary observer writes: "Among the Grachts, the Tygersgracht is the most stately and most pleasant, both for the goodliness of its buildings, and the ornamentation of its streets, which afford a very agreeable shadow to those who pass along the street".[18] The Prinsestraat (present Jalan Cengkeh), which in the beginning formed the street that leads to the Castle, were established as an urban center, connecting the Castle south gate with the City Hall, forming an impressive vista on the seat of government.[16]

This eastern settlement of Batavia was protected by a long canal to the east of the settlement, forming a link between the castle moat and the Ciliwung river bend. This canal was not parallel with Tijgersgracht but slightly angled. The overall construction of the canal took more than 160,000 reals, and these were paid not by the Company, but mainly by the Chinese and other Europeans; partly because the Company had spent for the strengthening of the Castle (which was done by slaves and prisoners).[16] This short-lived outer canal would be redesigned few years after the Siege of Batavia.

Completion of the city wall

To the east of Batavia, Sultan Agung, king of the Mataram Sultanate (1613–1645) attained control of most of Java by defeating Surabaya in 1625.[5]:31 On August 27, 1628, Agung launched the Siege of Batavia.[9]:52 In his first attempt, he suffered heavy losses, retreated, and launched a second offensive in 1629.[5]:31[9]:52–53 This also failed; the Dutch fleet destroyed his supplies and ships, located in the harbors of Cirebon and Tegal.[9]:53 Mataram troops, starving and decimated by illness, retreated again.[9]:53 Sultan Agung then pursued his conquering ambitions in an eastward direction[9]:53 and attacked Blitar, Panarukan and the Kingdom of Blambangan in Eastern Java, a vassal of the Balinese kingdom of Gelgel.[9]:55

Following the siege, it was decided that Batavia would need a stronger defense system. Based on the military defensive engineering ideas by Simon Stevin, a Flemish mathematician and military engineer, governor-general Jacques Specx (1629-1632)[10]:463 designed a moat and city wall that surrounded the city; extensions of the city walls appeared to the west of Batavia and the city became completely enclosed. The city section within the defense lines was structured according to a grid plan, criss-crossed with canals that straightened the flow of the Ciliwung river. This area corresponds to present day Jakarta Old Town.

City growth

In 1656, due to a conflict with Banten, the Javanese were not allowed to reside within the city walls and consequently settled outside Batavia. Only the Chinese people and the Mardijkers were allowed to settle within the walled city of Batavia. In 1659, a temporary peace with Banten enabled the city to grow and, during this period, more bamboo shacks appeared in Batavia. From 1667, bamboo houses, as well as the keeping of livestock, were banned within the city. Within Batavia's walls, the wealthy Dutch built tall houses and canals. As the city grew, the area outside the walls became an attraction for many people and suburbs began to develop outside the city walls.

The area outside the walls was considered unsafe for the non-native inhabitants of Batavia. The marsh area around Batavia could only be fully cultivated when a new peace treaty was signed with Banten in 1684 and country houses were subsequently established outside the city walls. The Chinese people began with the cultivation of sugarcane and tuak, with coffee a later addition.

The large-scale cultivation caused destruction to the environment, in addition to coastal erosion in the northern area of Batavia. Maintenance of the canal was extensive due to frequent closures and the continuous dredging that was required.

Massacre of Chinese

The Batavian hinterland's sugar industry deteriorated in the 1730s.[13]:169[19]:29 There were numerous unemployed people and growing social disorder.[13]:169 In 1739, 10,574 registered Chinese were living in the Ommelanden.[13]:53 Tensions grew as the colonial government attempted to restrict Chinese immigration by implementing deportations to Ceylon and South Africa.[8] The Chinese became worried that they were to be thrown overboard to drown and riots erupted.[8][20]:99 10,000 Chinese were massacred between 9 October 1740 and 22 October.[8] During the following year, the few remaining Chinese inhabitants were moved to Glodok, outside the city walls.[21]

Hinterland

The area outside the walls (Dutch: Ommelanden; the surrounding area)[13] was considered unsafe for the non-native inhabitants of Batavia. The area was an important source of food crops and building materials.[13] The VOC set up a local government (Dutch: College van Heemraden; District Council) in 1664, but this only became fully functional in 1682.[13]:10 The marsh area around Batavia could only be fully cultivated when a new peace treaty was signed with Banten in 1684. Country houses were subsequently established outside the city walls. The Chinese people began with the cultivation of sugarcane[13]:6[22] and tuak, with coffee a later addition.

The large-scale cultivation caused destruction to the environment, in addition to coastal erosion in the northern area of Batavia. Maintenance of the canal was extensive due to frequent closures and the continuous dredging that was required.

Other than country houses, most people in the Ommelanden people lived in various single ethnithicy kampungs, each with its own headman.[13]:5[23]

Society

Batavia was founded as the trade and administrative center of the Dutch East India Company; it was never intended to be a settlement for the Dutch people. Coen founded Batavia for trade, with city's inhabitants taking care of the production and supply of food. As a result, there was no migration of intact Dutch families and there were few Dutch women in Batavia. A mixed society was formed, as relationships between Dutch men and Asian women did not usually result in marriage, and the women did not have the right of going with men who returned to the Dutch Republic. This societal pattern created a mixed group of mestizo descendants in Batavia. The sons of this mixed group often traveled to Europe to study, while the daughters were forced to remain in Batavia, with the latter often marrying Dutch East India Company (VOC) officials at a very young age.

As the VOC preferred to maintain complete control over its business, a large number of slaves was employed. Batavia became an unattractive location for people who wanted to establish their own businesses.

The women in Batavia developed into an important feature of the social network of Batavia; they were accustomed to dealing with slaves and spoke the same language, mostly Portuguese and Malay. Eventually, many of these women effectively became widows, as their husbands left Batavia to return to the Netherlands, and their children were often removed as well. These women were known as snaar ("string").

Most of Batavia's residents were of Asian descent. Thousands of slaves were brought from India and Arakan and, later, slaves were brought from Bali and Sulawesi. To avoid an uprising, a decision was made to free the Javanese people from slavery. Chinese people made up the largest group in Batavia, with most of them merchants and labourers. The Chinese people were the most decisive group in the development of Batavia. There was also a large group of freed slaves, usually Portuguese-speaking Asian Christians, that was formerly under the rule of the Portuguese. The group's members were made prisoners by the VOC during numerous conflicts with the Portuguese. Portuguese was the dominant language in Batavia until the late 18th century, when the language was slowly replaced with Dutch and Malay. Additionally, there were also Malays, as well as Muslim and Hindu merchants from India.

Initially, these different ethnic groups lived alongside each other; however, in 1688, complete segregation was enacted upon the indigenous population. Each ethnic group was forced to live in its own established village outside the city wall. There were Javanese villages for Javanese people, Moluccan villages for the Moluccans, and so on. Each person was tagged with a tag to identify them with their own ethnic group; later, this identity tag was replaced with a parchment. Reporting was compulsory for intermarriage that involved different ethnic groups.

Within Batavia's walls, the wealthy Dutch built tall houses and canals. Commercial opportunities attracted Indonesian and especially Chinese immigrants, with the increasing population numbers creating a burden upon the city. In the 18th century, more than 60% of Batavia's population consisted of slaves working for the VOC. The slaves were mostly engaged to undertake housework, while working and living conditions were generally reasonable. Laws were enacted that protected slaves against overly cruel actions from their masters; for example, Christian slaves were given freedom after the death of their masters, while some slaves were allowed to own a store and make money to buy their freedom. Sometimes, slaves fled and established gangs that would roam throughout the area.

Though from the beginning of the VOC establishment Batavia became the political and administrative center of the Dutch East Indies as well as the major port in Southeast Asian trade, the population of the city proper remained relatively small. In the early 1800s, estimates of its population were still smaller than that of Surabaya, though it would overtake that city by the end of that century: the first complete census survey of 1920 returned a population of 306,000, compared to 192,000 for Surabaya, 158,000 for Semarang and 134,000 for Surakarta. By then the population grew fast, as ten years later it exceeded half a million.[24]

Malaria

In the 18th century, Batavia became increasingly affected by malaria epidemics, as the marsh areas were breeding grounds for mosquitos.[25] The disease killed many Europeans, resulting in Batavia receiving the nickname, "Het kerkhof der Europeanen" ("the cemetery of the Europeans").[26][27] Wealthier European settlers, who could afford relocation, moved to southern areas of higher elevation.[20]:101 Eventually, the old city was dismantled in 1810.

Dutch East Indies (1800-1942)

After the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) went bankrupt and was dissolved in 1800, the Batavian Republic nationalized its debts and possessions, expanding all of the VOC's territorial claims into a fully-fledged colony named the Dutch East Indies. Batavia evolved from the site of the company's regional headquarters into the capital of the colony.

Southward expansion

In 1808, Daendels decided to quit the by-then dilapidated and unhealthy Old Town. A new town center was subsequently built further to the south, near the estate of Weltevreden. Batavia thereby became a city with two centers: Kota as the hub of business, where the offices and warehouses of shipping and trading companies were located; while Weltevreden became the new home for the government, military, and shops. These two centers were connected by the Molenvliet Canal and a road (now Gajah Mada Road) that ran alongside the waterway.[28]

During the British interregnum (1811-1816), Daendels was replaced by Stamford Raffles.[3][29]:115–122[30][31]:25

After the 1740 massacre, it became apparent over the ensuing decades through a series of considerations that Batavia needed Chinese people for a long list of trades.[32]:49 Considerable Chinese economic expansion occurred in the late eighteenth century, and by 1814 there were 11,854 Chinese people within the total of 47,217 inhabitants.[32]:49

The city began to move further south, as epidemics in 1835 and 1870 encouraged more people to move far south of the port. This period in the 19th century consisted of numerous technological advancements and city beautification initiatives in Batavia, earning Batavia the nickname, "De Koningin van het Oosten", or "Queen of the East".

Abolition of Cultuurstelsel

The Dutch: Cultuurstelsel; Cultivation System was a government policy in the mid-nineteenth century which required a portion of agricultural production to be devoted to export crops. Indonesian historians refer to it as Indonesian: Tanam Paksa; Enforcement Planting. The abolition of the Cultuurstelsel in 1870 led to the rapid development of private enterprise in the Dutch Indies. Numerous trading companies and financial institutions established themselves in Java, with most settling in Batavia. Jakarta Old Town's deteriorating structures were replaced with offices, typically along the Kali Besar. These private companies owned or managed plantations, oil fields, or mines. The first railway line in Java was opened in 1867 and urban centers such as Batavia began to be equipped with railway stations.[33] Many schools, hospitals, factories, offices, trading companies, and post offices were established throughout the city, while improvements in transportation, health, and technology in Batavia caused more and more Dutch people to migrate to the capital—the society of Batavia consequently became increasingly Dutch-like. International trade activity occurred with Europe and the increase of shipping led to the construction of a new harbor at Tanjung Priok between 1877 and 1883.[34] The Dutch people who had never set foot on Batavia were known locally as Totoks. The term was also used to identify new Chinese arrivals, to differentiate them from the Peranakan. Many totoks developed a great love for the Indies culture of Indonesia and adopted this culture; they could be observed wearing kebayas, sarongs, as well as summer dresses.[35]

By the end of the 19th-century, the population of the capital Batavian regency numbered 115,887 people, of which 8,893 were Europeans, 26,817 were Chinese and 77,700 were indigenous islanders.[36] A significant consequence of these expanding commercial activities was the immigration of large numbers of Dutch employees, as well as rural Javanese, into Batavia. In 1905, the population of Batavia and the surrounding area reached 2.1 million, including 93,000 Chinese people, 14,000 Europeans, and 2,800 Arabs (in addition to the local population).[37] This growth resulted in an increased demand for housing and land prices consequently soared. New houses were often built in dense arrangements and kampung settlements filled the spaces left in between the new structures. This settlements proceeded with little regard for the tropical conditions and resulted in overly dense living conditions, poor sanitation, and an absence of public amenities.[38] In 1913, the plague broke out in Java.[38]

Also during the period, Old Batavia abandoned moats and ramparts experienced a new boom, as the commercial companies were re-established along the Kali Besar.[38] In a very short period of time, the area of Old Batavia re-established itself as a new commercial center, with 20th-century and 17th-century buildings adjacent to each other.

Dutch Ethical Policy

The Dutch Ethical Policy was introduced in 1901, expanding educational opportunities for indigenous population of the Dutch East Indies. In 1924 a law school was founded in Batavia.[39] The city’s population in the 1930 census was 435,000.[10]:50 The University of Batavia was established in 1941 and later became the University of Indonesia.[39] In 1946, the Dutch colonial government established the Nood Universiteit (Emergency University) in Jakarta. In 1947, the name was changed to Universiteit van Indonesië (UVI) (Indonesia University). Following the Indonesian National Revolution, the government established a state university in Jakarta in February 1950 named Universiteit Indonesia, comprising the BPTRI units and the former UVI. The name was later changed into Universitas Indonesia (UI).

National revival

Mohammad Husni Thamrin, a member of Volksraad, criticized the Colonial Government for ignoring the development of kampung ("inlander's area") while catering for the rich people in Menteng. Thamrin also talked about the issue of Farming Tax and the other taxes that were burdensome for the poorer members of the community.

Independence movement

In 1909, Tirtoadisurjo, a graduate of OSVIA (Training School for Native Officials), founded the Islamic Commercial Union (Sarekat Dagang Islamiyah) in Batavia to support Indonesian merchants. Branches in other areas followed. In 1920, Tjokroaminoto and Agus Salim set up a committee in Batavia to support the Ottoman caliphate.[39]

In 1926, espionage warned the Dutch of a planned revolt and PKI leaders were arrested. Andries C. D. de Graeff replaced Fock as governor-general and uprisings in Batavia, Banten, and Priangan were quickly crushed.[39] Armed Communists occupied the Batavia telephone exchange for one night before being captured. The Dutch sent prisoners to Banden and to a penal colony at Boven Digul in West Irian (West New Guinea) where many died of malaria.[39] On July 4, 1927 Sukarno and the Study Club founded the Indonesian Nationalist Association which became the Indonesian Nationalist Party (PNI) and later joined with the Partai Sarekat Islam, Budi Utomo, and the Surabaya Study Club to form the Union of Indonesian Political Associations (PPPKI).[39] A youth congress was held in Batavia on October 1928 and the groups began referring to the city as Jakarta. They demanded Indonesian independence, displayed the red-and-white flag, and sang the Indonesian national anthem written by W. R. Supratman. The Dutch banned the flag, the national anthem, and the terms Indonesia and Indonesian.[39]

Japanese occupation and national revolution era (1942-1949)

On March 5, 1942, Batavia fell to the Japanese. The Dutch formally surrendered to the Japanese occupation forces on March 9, 1942, and rule of the colony was transferred to Japan. The city was renamed Jakarta.

The economic situation and the physical condition of Indonesian cities deteriorated during the occupation. Many buildings were vandalized, as metal was needed for the war, and many iron statues from the Dutch colonial period were taken away by the Japanese troops. Civil buildings were converted into internment camps where Dutch people were imprisoned.

After the collapse of Japan in 1945, the area went through a period of transition and upheaval during the Indonesian national struggle for independence. During the Japanese occupation and from the perspective of the Indonesian nationalists who declared independence on August 17, 1945, the city was renamed Jakarta.[2] In 1945, the city was briefly occupied by the Allies and then was returned to the Dutch. The Dutch name, Batavia, remained the internationally recognized name until full Indonesian independence was achieved and Jakarta was officially proclaimed the national capital (and its present name recognized) on December 27, 1949.[2]

Mayors

The city of Batavia had a mayor (burgemeester) from 1916 to 1947.

- GJ Bishop (1916-1920)

- H. van Breen (1920-1920) Acting

- A. Meij Roos (1920-1933)

- EA Voorneman (1933 to 19 ??)

- A.Th. Boogaardt (Acting in 1941)

- EA Voorneman (1941 to 1942)

- A.Th. Boogaardt (1945-1947)

Born in Batavia

- Reinout Willem van Bemmelen, geologist

- Ben Bot, Dutch diplomat and government minister

- Huibert Boumeester, rower

- Tonke Dragt, writer and illustrator of children's literature

- Boudewijn de Groot, singer/songwriter

- Michel van Hulten, politician

- Yvonne Keuls, writer

- Taco Kuiper, investigative journalist and publisher

- Pieter Mijer, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, 1866–1872

- Carel Jan Schneider, known by the pseudonym F. Springer, a Dutch foreign service diplomat and writer

- Francis Steinmetz, officer in the Royal Netherlands Navy who escaped from Colditz

- Frans Tutuhatunewa, president of the Republic of South Maluku (internationally unrecognized)

- Eddy de Neve, member of the first Netherlands national football team

See also

- Kota Tua Jakarta

- History of Jakarta

- Timeline of Jakarta

- List of colonial buildings and structures in Jakarta

References

- 1 2 Vickers A. A History of Modern Indonesia Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0521542626

- 1 2 3 4 Waworoentoe WJ. Jakarta Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc; accession date August 30, 2015.

- 1 2 Ricklefs MC. A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1200 Palgrave Macmillan, 4th edition, Sep 10, 2008. ISBN 9781137149183

- ↑ Liebenberg, Elri; Demhardt, Imre (2012). History of Cartography: International Symposium of the ICA Commission, 2010. Heidelberg: Springer. p. 209. ISBN 978-3-642-19087-2.

The United Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC in Dutch, literally "United East Indian Company")...

- 1 2 3 Drakeley S. The History of Indonesia. Greenwood, 2005. ISBN 9780313331145

- ↑ de Vries J, van der Woude A. The First Modern Economy. Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500–1815. Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780521578257

- ↑ Ricklefs MC. A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1200. MacMillan, 2nd edition, 1991ISBN 0333576896

- 1 2 3 4 Gimon CA. Sejarah Indonesia: An Online Timeline of Indonesian History. gimonca.com 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ricklefs MC. A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1200 Palgrave Macmillan, 3rd edition, 2001. ISBN 9780804744805

- 1 2 3 Cribb R, Kahin A. Historical Dictionary of Indonesia. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 2nd edition ISBN 9780810849358

- 1 2 3 "Batavia". De VOCsite (in Dutch). de VOCsite. 2002–2012. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ de Haan 1922, p. 44-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Kanumoyoso, B. Beyond the city wall : society and economic development in the Ommelanden of Batavia, 1684-1740 Doctoral thesis, Leiden University 2011

- ↑ Robson-McKillop R. (translator) The Central Administration of the VOC Government and the Local Institutions of Batavia (1619-1811) – an Introduction. Hendrik E. Niemeijer HE.

- ↑ Lucassen J, Lucassen L. Globalising Migration History: The Eurasian Experience (16th-21st Centuries). Brill, 2014. ISBN 9789004271364

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 de Haan 1922, p. 46-7.

- 1 2 Bollee, Kaart van Batavia 1667.

- ↑ Gunawan Tjahjono 1998 & 113.

- ↑ Knight GR. Sugar, Steam and Steel: The Industrial Project in Colonial Java, 1830-1885 University of Adelaide Press, 2014. ISBN 9781922064998

- 1 2 Ward K. Networks of Empire: Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company. Cambridge University Press, 2009. ISBN 9780521885867

- ↑ Vaisutis, Justine; Martinkus, John; Batchelor, Dr. Trish (2007). Indonesia. Lonely Planet. p. 101. ISBN 9781741798456. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ↑ Blussé, L. Strange Company. Chinese settlers, mestizo women and the Dutch in VOC Batavia. Dordrecht: Floris Publication, 1986.

- ↑ de Haan 1922, p. 469.

- ↑ Hiroyoshi Kano, Growing Metropolitan Suburbia: A Comparative Sociological Study on Tokyo and, Yayasan Obor Indonesia, 2004, pp. 5-6

- ↑ van der Brug PH. Malaria in Batavia in the 18th century. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1997; volume 2, issue 9, pages 892–902. PMID 9315048

- ↑ Pols H. Notes from Batavia, the Europeans' graveyard: the nineteenth-century debate on acclimatization in the Dutch East Indies J Hist Med Allied Sci 2012; volume 67, issue 1, pages 120–148. DOI 10.1093/jhmas/jrr004 PMID 21317422

- ↑ van Emden,, F. J. G.; W. S. B. Klooster (1964). Willem Brandt, ed. Kleurig memoriaal van de Hollanders op Oud-Java. A. J. G. Strengholt. p. 146.

- ↑ Gunawan Tjahjono, ed. (1998). Architecture. Indonesian Heritage. 6. Singapore: Archipelago Press. p. 109. ISBN 981-3018-30-5.

- ↑ Hannigan T. A Brief History of Indonesia: Sultans, Spices, and Tsunamis: The Incredible Story of Southeast Asia's Largest Nation. Tuttle Publishing, 2015. ISBN 9780804844765

- ↑ Hannigan T. Raffles and the British Invasion of Java. Monsoon Books, 2013. ISBN 9789814358859

- ↑ National Information Agency. Indonesia 2004; an official handbook. Republic of Indonesia.

- 1 2 Dobbin C. Asian Entrepreneurial Minorities : Conjoint Communities in the Making of the World-Economy 1570–1940. Richmond: Curzon. 1996 ISBN 9780700704040

- ↑ Gunawan Tjahjono 1998 & 116.

- ↑ Teeuwen, Dirk (2007). Landing stages of Jakarta/Batavia.

- ↑ Nordholt, Henk Schulte; M Imam Aziz (2005). Outward appearances: trend, identitas, kepentingan (in Indonesian). PT LKiS Pelangi Aksara. p. 227. ISBN 9789799492951. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ↑ Teeuwen, Dirk Rendez Vous Batavia (Rotterdam, 2007) Archived July 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Oosthoek's Geïllustreerde Encyclopaedie (1917)

- 1 2 3 Gunawan Tjahjono 1998 & 109.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Beck S. South Asia 1800-1950: Indonesia and the Dutch 1800-1950

Works cited

- de Haan, F. (1922). Oud Batavia. 1. Batavia: G. Kolff & Co, Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen.

- Gunawan Tjahjono, ed. (1998). Architecture. Indonesian Heritage. 6. Singapore: Archipelago Press. ISBN 981-3018-30-5.

- Kaart van het Kasteel en de Stad Batavia in het Jaar 1667 [Map of the Castle and the City Batavia in year 1667] (Map) (Den Haag ed.). 50 rhijnlandsche roeden (in Dutch). Cartography by J.J. Bollee. G.B. Hooyer and J.W. Yzerman. 1919.

Further reading

- Batavia: Queen City of the East G. Kolff & Company, 1925

- The Social World of Batavia: European and Eurasian in Dutch Asia by Jean Gelman Taylor, University of Wisconsin Press, January 1, 1983

- The Archives of the Kong Koan of Batavia, edited by Lâeonard Blussâe, Menghong Chen, Brill, January 1, 2003 - accounts of the Chinese Indonesian experience in Batavia

- Jakarta-Batavia: socio-cultural essays C. D. Grijns, P. Nas

- Lombard, Denys. Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale