Boho, County Fermanagh

| Boho | |

| Irish: Botha | |

Boho Church of Ireland |

|

Boho |

|

| District | Fermanagh and Omagh |

|---|---|

| County | County Fermanagh |

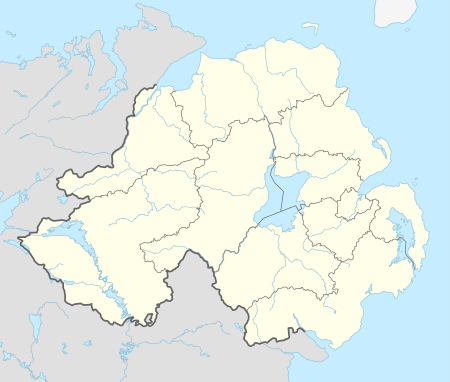

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ENNISKILLEN |

| Postcode district | BT74 |

| Dialling code | 028, +44 28 |

| EU Parliament | Northern Ireland |

| NI Assembly | Fermanagh and South Tyrone |

|

|

Coordinates: 54°20′59″N 7°47′45″W / 54.3497°N 7.7957°W

Boho (pronounced /ˈboʊ/ BOH,[1] from Irish: Botha, meaning "huts")[2] is a hamlet and a civil parish 11 kilometres (7 mi) covering approximately 12 km × 7 km (7 mi × 4 mi) southwest of Enniskillen in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland.[3] It is situated within Fermanagh and Omagh district.

This area contains a high density of historically significant sites stretching from the Neolithic Reyfad Stones, through the Bronze Age/Iron Age (Aghnaglack Tomb) and medieval (High Crosses) to comparatively recent historical buildings such as the Linnett Inn.

Boho parish also has a high biodiversity of flora and fauna due in part to the niches offered by the limestone karst substrata. The three mountains found within the parish; namely Glenkeel, Knockmore and Belmore provide a landscape varying from high craggy bluffs, with views of neighbouring counties, to low, flat bogland punctuated by streams and lakes.[4] Below this landscape are two of the three most cave-rich mountains in Northern Ireland,[5] featuring the deepest cave system in Ireland at Reyfad Pot, the deepest daylight shaft in Ireland at Noon's Hole, as well as popular caves for local outdoor adventure centre groups at the Boho Caves and the nearby Pollnagollum Coolarkan.[5]

History

Ancient origins

Boho is an anglicisation of the Irish Botha, which is the plural of Both, an old word for tent, hut or booth. This is a truncation of Bhotha Mhuintir Uí Fhialáin, Bothach ui fhialain in Breifney or mBothaigh I Fhialain, which translates as the huts of the Uí Fhialáin.[6][7] The surname Ó Fialáin is sometimes rendered as Phelan.

This area has a long history of habitation as evidenced by the ancient Neolithic patterned stones in the townland of Reyfad, dating to the late Stone Age, early Bronze Age period (nearly 4000 years ago) that are classified as a scheduled monument.[8] Further remnants of Neolithic habitation were unearthed by the Enniskillen archeologist Thomas Plunkett in 1880 when he discovered an ancient settlement 6 1⁄2 m (21 ft) beneath the surface of a peat bog (the coal bog) in the townland of Kilnamadoo.[9][10] More neolithic remnants were also unearthed in the townland of Moylehid again by Thomas Plunkett when he discovered the Eagle’s Knoll Cairn passage tomb and Moylehid ring in 1894.[11]

Bronze Age evidence of habitation in the area was discovered when George Coffey (1901) unearthed a copper knife, which is currently on display in the Dublin collection.[12]

Iron Age artifacts were discovered in the Carn townland of Boho (1953), consisting of remnants of a hearth at the foot of an escarpment dating to first millennium AD.[13]

Later evidence of Danish raiders to this area came in the form of an iron spear head, found in a Cromleac in Boho, on display at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin.[14][15]

History

The inscriptions on the Neolithic Reyfad stones constitute the first markings or writings from the Boho area, however their meaning has still to be dicephered.[8] Thousands of years later the region covering the Boho area was inhabited by the Erdini, Ptolemy (150 AD).[16]

In 700 AD, the two predominant tribes in the region were the Cenel Enda and Cenel Laegaire, whose boundaries followed areas similar to Clanawley, and the Magheraboy.[17] There was a third tribe in this region known as the Fir Manach but their territory did not cover the Boho region.[17] At this time, the barony of Clanawley extended into the north of County Cavan.[17] Later the Boho area was considered to be in West Bréifne, also known as Bréifne Ó Ruairc.[18]

According to research, the Boho area was mentioned by name in (628 AD) in the Annals of Ulster in which Suibne Menn of the Cenél nEógain kindred of the northern Uí Néill, reigning High King and son of Fiachra defeated his distant cousin Domhnall, son of Aedh (Domnall mac Áedo). This event was also described in The Annals of Tigernach (630 AD) as "Cath Botha in quo Suibne Mend mac Fiachrach uictor erat, Domnoll mac Aedha fuigit".[19] In the first part of the 9th century the area of Boho or as it was written Botha eich uaichnich, was linked to the encompassing territory known as Tuath Ratha (Tir Ratha) and also to a local patron saint St Faberin the Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee Óengus of Tallaght [20]

The area known as Túath Rátha (from Irish Túath Rátha, meaning "people/tribe of the fort"), is anglicised as Tooraah [21] and later as Toora and Trory.[22] It has also been retained as the name of the mountain Tura.[23] Tuath-Ratha is mentioned again in 1103 in the Annals of the Loch where “a fierce conflict between the men of the Lurg and the Tuath-Ratha, in which fell a multitude on both sides”. Again in 1119, it states that Cuchollchaille O'Baighellain, chief Ollamh (Ollam) of Erinn in poetry, was slain by the Feara-Luirg and by O' Flannagain of Tuath-Ratha.[24]

The rebellion in Boho.

There is a detailed account in the History of Enniskillen and in the History of the Maguires of the refusal of the people of the Boho area to pay annual tribute to the King of Fermanagh, Magnus MaGuidhir.[25][26]

The text of the account my McGuires historian is laid out as follows:

Accordingly, Maguire sent out his Bonaghs or

stewards to proceed on circuit for the tribute on his

behalf; and the Flanagan, of Toora, was the first to

refuse it, " till he saw his lord, to whom he would

give it on his feet ": and to show the guile of this

artful chief, he added with Irish blarney—"that they

would not store it more faithfully for him than

himself." With this rebel refusal the stewards seized

the cattle of Flanagan, and Flanagan pursued the

bonaghs to where we now call Glack, or Aghanaglack,

sometimes called Carn (Clais an Chairn), at Boho,

where a fight ensued for the cattle, in which many

were killed on both sides, including Flanagan and 15

of Maguire's party, and while the conflict was taking

place "the women and youngsters" of Toora took

back the cattle.[25]

This tract is a description by O Breislin (historian to Maguire) and O'Cassidy (physician to Maguire) of a time when MaGuidhir, the King of Fermanagh was unable to collect annual tribute from the seven tuaths of Fermanagh due to three years of infirmity. The account is written some several hundred years after the event for the McGuires and as such may contain blatant exaggerations on the magnanimity of the king, prophesies and connections to Irish mythologies.[25] The account mentions the Flannagans of Toorah, the area of Boagh or Boho Both Uí Fhialainand adjacent areas controlled by Mac Giolla Fheinnéin, the chief the Muinntear Fhuadacháin, Muinntear Leannáin, the church termoners for the parish of Inis Mhuighe Samh (Inismacasaint)and O Fialáin and Clann Mhe Garacháin associated with the Both Uí Fhialáin.[25][26]

Magnus MaGuidhir sent his bonaghs (representatives) to collect annual tribute from the southern edge of his dominion, namely O' Flannagáin's territory in Tuath Rátha.[26]

It is said that O' Flannagáin was reluctant to hand over the annual tribute to the bronaghs; stating that it would be as safe with him as it would be with the tribute collectors. Accordingly, the bonaghs forcefully collected this tribute in kind by rounding up cattle, preys and other stock.[26] However, O'Flannagan and his party pursued the men across Sliabh Dha Chon, close to Reyfad until they reached Galc Mhanchah or Clais an Chaim (also known as Glack) where a battle took place. During this struggle the women and children of Boho retrieved the cattle. Fifteen of McGuires men and 25 of the Boho men were killed including the chief Flannagan.[25][26] Incensed by reports of this rebellion, Maguire summoned his council of chiefs to decide on the compensation the Flannagan would pay. The result of a council of the other chiefs of Fermanagh was that since chief of the Flannagans had died in battle and they had lost 25 men, then there was no more need for settlement. This verdict was delivered by O Breislein, whom Maguire suspected of bias since they both came from the Fanad. Suspecting part of a wider rebellion, McGuidhr summoned his son Giollas Losa Ma Guidir from Briefne (heir apparent to the Fermanagh throne) and directed him to Sliabh dha Chon (mountain of the two hounds) which was previously known as Gleann Caom, the mountainous tract that lies between Fermanagh and Briefne Ui Kuairc (Brienfny O Rourke), lying within the Boho area at that time.[26] He counseled his son about the area, since it was the place where Fionn lost his two hounds 'through devilry or magic of the children of Lir'.[26] He was then to make his way to his brother in Beal Atha Seannaigh (Ballyshanon) and tell him (O Domhnaill) of the rebellion.[26]

Maghnus and Giolla 'losa then enlisted the help of some 700 men from Tyrconnell (Tir Chonnail) including Gallagher (O Gallchubhair), Bohill (O Baoighill) and the three Sweenys (Mac Suibhnes) who proceeded from Ath Seanaigh to Leac na nArm (Lack) and did not stop until they had reached to Sliabh Dha Chon.[26] They first called in at Tuath Lurg to collect tribute from O Maoladuin. Since he did not have it they sent him to custody at Port Dobhrain at Knockninny. Next was the Tuath of Tir Cheannada where Clann Mhe Guinnnseannain, O'Duibhain, O Seaghdhannain and Clann Mhic Anuisce lived on the hill known as Craobh Ui Fhadachain, where the Muintear Fhuadachain used to be. Giolla Tosa asked for tribute which they could not provide. He then ordered the arrest of Ma Guinnsionnain and all the tribe present to set an example also had them sent to Port Dobhrain.[26] They proceeded then to have all the heads of the seven tuaths bound and fettered and sent to Port Dobhrain to extract the eric that they owed .[25][26] After this tour of the county, O Domhnaills men camped at the top of Gleann Dorcha (dark valley) and then at Srath na d'Tarbh in the townland of templenaffrin which is named after the fight of the two bulls, Donn Cuailgne and Finnbheannach. Eventually the tribute from all seven Fermanagh tuaths was paid with eric (compensation) at Port Dobhrain, the Maguires royal residence at Knockninny.[26] An eric of 700 milk cows was levied on O'Flanagan as a balance for the 700 men Maguire had employed to enforce his tribute collection who had come from Tyrconnell (Donegal).[26] The new Flannagan together with the heads of the seven tuaths were then made swear allegiance to McGuidhr and the new Flannagan was officially recognized. There then followed three days of feasting "to the high, to the lowly, to the laity, to the clergy, to the druids, to the ollambs in the royal household, and to the Tyrconnell (Tir Chonnail) party".[26]

Later historical accounts of Túath Rátha described the region as extended from Belmore mountain to Belleek and from Lough Melvin to Lough Erne.[27][28][29]

In 1483, Boho is mentioned in The Annals of Ulster upon the death of John O'Fialain (Ua Fialain), "the Ollam in poetry" of the sons of Philip Mag Uidhir (McGuire) and herenagh of Botha.[30] Again in Annals of the Four Masters (Mícheál Ó Cléirigh, 1487) the area is mentioned on the death of Teige (Tadhg), the son of Brian Mac Amlaim Mag Uidhir (McGuire), son of Auliffe Mag Uidhir, who had first been Parson of Botha, and then Vicar of Cill-Laisre (Killesher)[31][32] In 1498 there are reports of Maine, the son of Melaghlin, son of Matthew Mac Manus, slain in Botha-Muintire-Fialain, by the sons of Cathal Ua Gallchobair (O'Gallagher).[33][34][35] There is also mention in 1520 of Nicholas, the son of Pierce O'Flanagan, Parson of Devenish, who was "unjustly removed from his place by the influence of the laity, and died at Bohoe".[36] In 1552 there is a mention of Tadhg, the son of Tadhg, son of Eoghan O'Ruairc, who was slain in treachery in Bothach-Ui-Fhialain, by the Davine, son of Lochlainn.[24]

Boho is again mentioned during the inquisition of church lands held during the reign of James I of England in 1609–1610, described as Boghae.[37] At that point in time, the land was divided amongst septs, the head of which was a herenagh who paid tribute to the bishop of Clogher. The herenagh in Boho at that time was known as O'Fellan and under him was another sept "in the nature of a herenagh", called Clan McGarraghan (Mac Arachain).[37][38] O'Fellan is described as having a free 'tate' or tathe, called Karme (Carn), to himself, and another, called Rostollon, which was divided among his sept of 'doughasaes' equally. The document also describes an area of land called KillmcIteggart or Farrennalter, one part of which belonging to the parson, and the other to the vicar.[37]

In 1610 the area of Boho is described as extending into the barony of Clonawley (Clanawley), whose limits are bounded by the lands of Aghara in the west, Sleveamwell Hill in Clanawley in the east, the river of Bealaghmore in the north, and by Ourae mountain, also to the north.[37] By 1837, before parish boundaries were altered, the parish was still quite large and was described as containing 2,581 inhabitants, comprising 15,058 1⁄2 statute acres, of which 6,151 1⁄4 are in the barony of Magheraboy and 8,907 1⁄4 in that of Clanawley.[39] In those times this area also included the village of Belcoo.[39] In more recent times due to restructuring the parish grew smaller until the mid-19th century when it contained 51 townlands.[40] Today the number of townlands in the area stands at 46.[41]

The name of a nearby school, Portora Royal School in Enniskillen (established 1618),[42] is purported to be derived from the Irish Port Abhla Faoláin, meaning "landing place of the apple trees of Faolán". This may refer to Bhotha Mhuintir Uí Fhialáin, a tribe that inhabited the Boho area.[43]

In the mid-17th century, historical records mention John McCormick, son of Cormick, who received a grant of land at Drumboy, Boho. It is stated that he gave evidence against Lord Conor Maguire at his trial for treason and was later appointed as one of the commissioners who took evidence on the massacres of 1641. After his death, his estates in Boho and Cleenish were left to his wife and nephew William McCormick.[38]

Places of interest

Boho High Cross

The High Cross in Boho graveyard (grid ref H1167 4621) is on an eminence overlooking the Sacred Heart Church (patron St Feadhbar or St Faber) in the townland of Toneel North.[44][45] It has been speculated to date from as early as the 10th century and comprises a weathered sandstone shaft.[46] Excavation of the cross have suggested that it was moved to its present position in 1832, when the site was first reused for Roman Catholic worship, the new church being built in the original graveyard slightly south of the old one.[45][46]

The west face of the cross shaft depicts the presentation of the John the Baptist in the Temple. The central figure holds a child in their arms and is accompanied by a figure either side. Above this carving is the Baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist with the River Jordan flowing between their feet.[47] The East face of the cross shaft depicts Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden together with a tree and serpent who is looking at one of the figures.[47] The accompanying socketed base of red sandstone in which the shaft rests measures 90 x 88 cm at ground level and 62 cm in height.[47] There is conjecture that the base of the cross is a bullán which men would resort to in cases of childless marriages.[48] The existing doorway of the nearby Church of Ireland at Farnaconnell is thought to have originated from the pre-reformation church at Toneel North.[49]

Reyfad Stones

The Reyfad Stones are neolithic stones with cup and ring mark inscriptions similar to markings found at Newgrange. These have been designated as a scheduled monument by the Northern Ireland Environmental Agency (SM 210:13).[50] These are located in farmland at some distance behind the Sacred Heart Church in Boho. Access is by permission.[51][52]

Noon's Hole

Noon's Hole lies approximately 5 kilometres (3 mi) north west of the centre of Boho. At 81 metres (266 ft), this pothole is the deepest daylight shaft in Ireland.[5][53]

Aghanaglack Tomb

This Neolithic dual court tomb was discovered by Prof. Oliver Davies(1938).[54]

Boho Waterfall

This is located at the entrance of Pollnagollum Cave in Belmore Forest.[55]

Boho Caves

Boho caves are the seventh longest cave passage system in Northern Ireland and have been designated as an ASSI.[56] They are the only example of a joint-controlled maze cave in Northern Ireland.[56] They also contain the only Irish modern-day record of the cave-dwelling water beetle (Agapus biguttatus).[56]

Belmore Forest

Belmore forest (Grid ref:H127418) on the slopes of Belmore Mountain is a coniferous forest that covers approximately 863.99 ha (2134.96 acres). It is included in the UNESCO Marble Arch Caves Global Geopark. The forest contains Forestry houses, Coolarkan Quarry and Pollnagollum Cave.

Balintempo Forest

Balintempo forest is predominantly a coniferous forest plantation with areas of blanket bog and rocky outcrops of sandstone. Together with the forests of Carrigan, Big Dog, Conagher and Lough Navar they form the largest continuous tract of coniferous forest in Northern Ireland. The forest also forms part of the Ulster Way and the Marble Arch Caves Global Geopark. The area is notable for Aghanaglack chambered cairn

Eagle's Knoll Cairn and Moylehid Ring

This neolithic site associated with the townland of Moylehid contains the Eagle’s Knoll Cairn passage tomb and the Moylehid ring cairn. These are scheduled historic monuments.

St Fabers Well and St Fabers Bullan

Situated in the townland of Killydrum, St Fabers Well and Bullan are associated with the patron saint of the local Sacred Heart Church.

Boho Sacred Heart Chrurch

Built by the Rev Nicholas Smith in 1832, in townland of Toneel North possibly on the site of some ancient religious site. This is a four bay hall with a squared rubble gable and billcote renovated in 1913. The site is notable for the 10th-century High Cross.[57]

Boho Parish Church of Ireland

Built in 1777 in the townland of Farnaconnell. A small three bay tower and hall church with round headed windows. The church was restored in 1830 and contains elements of medieval church 1 km north in archway entrance to the vestibule. (Grid Ref: N54.35475 W007.81112) [57]

The Linnet Inn

The Linnet Inn, situated near Boho Cross-Roads is over 200 years old[40] and is one of the few remaining thatched public houses in Ireland. It contains a classic style open hearth fire and a unique "cave bar" in homage to the local caves designed and constructed by its previous owner, Brian McKenzie.[5]

Places of spiritual and religious significance

The Boho area is replete with sacred/religious sites, from the present age such as the Church of Ireland at Farnaconnell and the Sacred Heart Church in Toneel North, to older pre-reformation churches. There were also places of worship which were historically situated outside conventional buildings that were used in times of religious and political struggle, when the need for secrecy was premium. These were found in the 18th century in places such as Aghakeeran where there was a Mass Garden and in nearby Aghanaglack during the same period, where there was a Mass Cave "Prison".[58][59]

Further up on the mountain in Knocknahunshin there was records of a Mass Garden, although this may refer to a place known locally as the Mass Rock.[58][59] During the 18th century, in the parish of Boho (Inishmacsaint), there was a Mass Garden in Tullygerravra.[58][59] In earlier periods, around the time of James I's inquisition into church lands, there were Mass Altars at Drumgamph, Fintonagh (which was also in the parish at this time) and Killyhoman as well as a report of a holy well in the Killydrum townland.[58][59]

There may have been a third traditional church in Boho parish called Templemollem or the Church of the Mill, which is mentioned in the Survey of 1603 and in the Inquisition of 1609.[49] This was the chapel of ease called Templemullin on a tate of land owned by the sept of the McGaraghan which had an annual tribute to pay to the former Lisgoole Abbey of five gallons of butter and one axe.[37] It is also thought that the pre-reformation church in Toneel North may have been built on an even older a pre-Christian pagan amphitheatre.[49]

Agriculture

Livestock and crops

Boho is a mainly pastoral area devoted to grazing animals.

One of the difficulties encountered in livestock farming in the area aside from the high rainfall is that limestone grassland is low in some minerals necessary for grazing animals in the winter such as copper, selenium, phosphorus and magnesium.[60] Throughout the winter months, the cattle are kept indoors and fed on a diet of silage, hay and some mineral supplements.

There is little arable land in Boho and this is usually set aside for domestic use. Due to low farming income, there are few people that can make a living as full-time farmers in the area, rather there is a mixture of people who derive some income from faming but for the most part their main incomes derive from other sources. The positive side to this low intensity agriculture system is that Boho still retains a high diversity of environmentally important species that are in decline on a national scale found in species rich hay meadows, pastures and semi-natural habitats.[61][62]

Some areas of land in Boho are managed under the Environmentally Sensitive Area (ESA) scheme, with more (ecologically) significant areas being designated as Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) or as Special Areas of Conservation (SAC). Farmers receive ESA payments for low-intensity farming, i.e. cutting a meadow after the grass and wild herbs have seeded (ESA scheme).[63] Livestock (cows) were traditionally fed hay in the winter months as far up as the early 1980s, but modern methods of silage has overtaken this practice due to its higher nutritional value.

Harvesting hay

Traditional hay making in the Boho was a communal endeavour. Neighbours of the farmer and his family would gather round to help "win" the hay before any sign of rain. This was a long and arduous job compared to the modern process. Local people might even take a day off their regular job for this sole purpose. The meadow was cut using a scythe (originally), and then in more modern times by tractor with a side-mounted mower blade.[1] The grass swathes would be turned over by means of a hay rake and if the grass was dry enough it would be tedded with a pitchfork. The person that was tedding would lift as much as he/she could with a pitchfork and then shake it out vigorously over the ground. Once the grass was dry enough, the loose hay would be gathered into rows with hay rakes (this tedding might be repeated depending on how dry the grass was). The rows could also be made into small "laps" or "lappins" which are circularised stacks of dried grass.[64] The invention of a hay-right or tedding machine connected to the power take-off (PTO) of a tractor made tedding a lot less labour-intensive.

Once the tedding process had finished, the hay was made into a ruck. In Boho, depending on the moisture of the ground, it was traditional to place some branches on the ground or old hay to stop the bottom of the new ruck getting wet. The ruck was constructed by two or three people pitching up hay to a person on top of the ruck (sometimes a child) who tramped the hay down so that it was compact. When the ruck was high enough, usually the height of the person pitching the hay plus the length of their pitchfork, somebody would pull out the bottom circumference of the ruck and pitch that hay up on top as well.[1] Two hay ropes made with a twister were usually thrown over the top of the ruck at right angles to each other and secured by pulling out a piece of hay at the bottom of the ruck and making another short attachment, so that the ropes and the bottom of the ruck could be connected. After this was done, the ruck would be "dressed" by raking down the outside so that water would run off the top during the rain. The surrounding ground was raked for hay, which was transferred over to the next ruck.[1]

The highlights of "winning the hay" would be having tea and "fadge" in the meadows, or riding on the hay if it was brought to the hay shed.[1] Later on in the 1970s and 1980s the square baler was introduced, which revolutionized haymaking, making it far less labour-intensive. The 1980s–90s saw the introduction in the area of the circular disk mower which was used to directly transfer freshly cut grass to a silage pit. This changing technology was reflected in sociological changes; hay making was now no longer such a communal activity.[65]

Geological and hydrological environment

There are also three mountain peaks in Boho, namely Belmore 398 m (1,306 ft), Tullybrack, 386 m (1,266 ft) (incorporating Glenkeel, 373 m (1,224 ft) and Knockmore, 277 m (909 ft).[4][39]

The area of Boho is replete with karst features such as potholes, limestone pavement, dry valleys due to the predominant limestone bedrock which gives it significance at a national level. The specific types of bedrock take their names from local townlands such as Carn Limestone, Knockmore Limestone and Knockmore Sandstone.[66][67]

Karst features

There are three principal cave/karst systems in the Boho area, namely the Boho Caves, Reyfad–Glenkeel and Noon's Hole–Arch Cave system, situated under the mountains of Belmore, Tullybrack and Knockmore respectively. Many of these caves were first explored by local people, but the first detailed exploration and surveying of any caves in the area was undertaken by two cavers known as Édouard-Alfred Martel (the father of French speleology) and naturalist Lyster Jameson in 1895.[68]

Amongst the most notable caves beneath Belmore are Boho Caves, Aghnaglack Cave, Aghnaglack Rising, Pollbeg, Pollkeeran and Pollnagollum Coolarkan.[69]

Within the Tullybrack area are Braad Dry Valley, Carrickbeg (Bunty Pot), Fairy Cave, Ivy Hole, Little Reyfad, Mad Pot, Murphy's Hole, Oweyglass Caves, Pollbeg, Pollmore, Pollnacrom, Polltullybrack, Rattle Hole, Reyfad Pot and Seltanacool Sinks.[66][67]

The most notable caves in the Knockmore region include Noon's Hole, Arch Cave, Aughakeeran Pot, Crunthelagh Sink, Killydrum Sink, Old Barr Sink, Pollanaffrin and Seltanahunny Sink.[66][67]

Rivers and loughs

Rivers passing through Boho include the Sillees River which runs from Lough Navar Forest Park to Lower Lough Erne and its tributaries, the Screenagh and Boho Rivers.[70] There are also five major streams which drain into the Reyfad/Carrickbeg catchment area and are linked to the Carrickbeg resurgence.[70] One of these streams, entering Polltullybrack (second entrance to Reyfad Pot), is known as the Reyfad stream.[70]

There are four loughs associated with the civil parish of Botha, including Lough Nacloyduff (Loch na Cloiche Duibhe) which is in the townland of Clogherbog and Lough Acrottan (Loch an Chrotáin) in Glenkeel.[71][72] There are two other lakes associated with older parish boundaries, those of Carran and Ross Loughs.

Lough Nacloyduff (meaning the lake of the Dark Pit or digging) is about 1-acre (4,000 m2) in surface area. To the north on Knockmore Mountain are some yellow sandstone cliffs which contain "the lettered caves". These three caverns, two of them artificial in appearance, include oghamic style writing on their walls, consisting of crosses and star like shapes inside rectangles.[73]

November 2009 flooding

The Boho is also prone to regular flooding. One of the most recent events was in November 2009. With water in Lough Erne at its highest level since records began,[74] the Sillees River, which flows through the parish, burst its banks causing traffic disruption for several days. The flooding affected Corr Bridge, Drumaraw, Muckenagh, Carran Lake, Samsonagh and Mullygarry. Killyhommon Primary School had to be closed as drivers struggled to negotiate floods.[75]

Flora and fauna

Flora

As a consequence of the local geology and low intensity farming practices, the Boho area has a high biodiversity of floral habitat types that is almost unparalleled in the whole of Northern Ireland as evidenced by the number of Areas of Special Scientific Interest, provisional ASSI's (pASSI), candidate Special Areas of Conservation (cSAC) and proposed Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (pAONB).[66][76][77][78][79] These range from open freshwater lakes to high calcareous grasslands and upland bogs.

Fen meadow is a classic Boho habitat type, consisting of wet fields locally described as a bog meadow, typified by the species devil's-bit scabious, bog thistle, sedges and occasionally tormentil, purple moor grass and rushes (Juncaceae). In Northern Ireland, this type of terrain only covers 0.4% of the total land area and has decreased by 18% over the last ten years mainly due to the 21% decrease in Fermanagh coverage.[80]

In more upland areas, drier habitats include calcareous grassland, which is very rare in a Northern Ireland context covering only 0.1% of the total land area, and which in only ten years, between 1990–2000, underwent a 7% decrease in coverage.[80] Calcareous grassland is species rich, typified by blue moor-grass, wild-mountain thyme, lady's bedstraw, fairy flax and lady's-mantle as well as fescue grasses, sweet vernal grass, bent grass, crested dog's-tail grass, carnation sedge Cyperaceae and devil's-bit scabious on the thin layer of soil which covers the limestone rock.[80][81] Within this type of habitat, limestone pavement can also often be found, which can promote an even greater diversity of species.

Limestone grassland habitat in Northern Ireland is exclusive to County Fermanagh from the Boho–Knockmore region to Cuilcagh Mountain Park, this habitat and its associated karst features are so environmentally important that the latter Marble Arch region was designated part of the European Geoparks Network, the Global Network of National Geoparks and the world's first International Geopark, consequently adding international significance to the Boho landscape.[82][83] In Boho, this type of land is often associated with dry stone walls, built from limestone, which are constructed in a peculiarly local style and are equally important source of biodiversity.

There are large areas of bog in Boho, typified by species such as bell heather, cross-leaved heath and ling (common heather).[84] Additionally species such as sundew (which are carnivorous) and bog asphodels can be found.

The woodlands of Boho consist of a mixture of plantation woodlands and semi-natural broadleaf woodlands (mainly ash and hazel).[85][86]

As well as these rich ecological resources, Boho is well known for its small field sizes, which provide many field boundaries of hedges and dry stone walls.[80]

Scheduled species

Added to the importance of the above habitats, the Boho area includes large numbers of rare and protected plant species specified as priority species by the Northern Ireland Environment Agency, including Irish eyebright (Euphrasia salisburgensis var. hibernica) which is located on the western edges of Boho near Knockmore cliffs,[87] small white orchid (Pseudorchis albida), also known as the white mountain orchid,[88] blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium bermudiana), which belongs to the American element of the Irish flora i.e. those plants being absent from any other part of Eurasia but exist in North America,[89] green-flowered helleborine (Epipactis phyllanthes),[90] Cornish heath (Erica vagans),[91] which is found near Boho, yellow bird’s-nest (Monotropa hypopitys),.[92]

Other notable species to be found in the area include Swedish pouchwort (Calypogeia suecica), a bryophyte last found in Aghahoorin near Boho in 1961,[93] bee orchid, (Ophrys apifera),[94] mountain avens (Dryas octopetala),[95] marsh helleborine, (Epipactis palustris)[96] and bird's-nest orchid (Neottia nidus-avis)[97] located in proximity to Boho Caves.

Fauna

Non-domestic animals in the Boho area include the Irish hare, wild goats, foxes, badgers, red squirrels, rats, mice and shrews and the occasional pine marten.[98][99] Amongst Northern Ireland's priority species are Daubenton's bat (Myotis daubentoni) which was observed in a nursery roost located in Boho Caves in July 1895.[100]

Bird species are also well represented in Boho. In 1998 the number of breeding species recorded in a random transect of Boho was 26 and in 1999 that number was 27.[98][101]

With regards to the palæontological, the complete skeleton of an Irish stag (Cervus elaphus) was retrieved from the area and is now housed in the National Museum in Dublin.[102]

Folk tales

There are many stories of originating from the Boho area which tell of faeries, faerie bushes, banshees, swallow holes (potholes) and ancient stones.[103]

One recurring mention is of a changeling or faerie who has a prodigious talent for music. The author (or the teller) of the tale states that the faerie has a particular flair when it comes to musical instruments, traditionally the fiddle or the pipes. He develops such a gift that anyone who listens will be enchanted by the music (like the Greek myth of the sirens). Commenting on the appearance of the faerie, the story teller recounts that he saw him living with two old brothers beyond the "dogs well" and he looked like a "wizened wee monkey" ...the story teller estimates his age to be around 10 or 11 years but it appears that he could still could not walk, rather, "bobbed". His gift on the tin whistle was second to none, his particular penchant being long-forgotten tunes. All of a sudden he disappeared, never to be heard of by the story-teller again.[104]

There are other folk tales surrounding St Febor or St Faber, who placed a curse on Baron O Phelans castle in Boho causing it to sink into the earth although there are no reports as to where in the area this castle was located.[103] Some of these tales are recounted in the old country song, "Ma na Bh Fianna (Monea) – The Plain of the Deer".[105]

Notable residents

- James Gamble, later American emigrant and co-founder of Procter & Gamble, was born in the Boho rectory in 1803.[106]

Bohos around the world

Places that share the same name as Boho around the world include Boho (also known as Fort Boho) in Bari, Somalia 11°56′00″N 50°53′00″E / 11.933333°N 50.883333°E,[107] Ras Boho, Somalia 11°56′00″N 50°55′00″E / 11.933333°N 50.916667°E[108] and Uadi Boho, Somalia 4°20′00″N 45°23′00″E / 4.333333°N 45.383333°E,[109] as well as Boho, Leyte, Philippines 11°19′00″N 124°20′00″E / 11.31667°N 124.3333°E,[110] and Boho, Australia 36°41′48″S 145°46′17″E / 36.696659°S 145.771354°E.[111]

See also

- List of places in County Fermanagh

- List of civil parishes of County Fermanagh

- List of townlands in County Fermanagh

- List of villages in Northern Ireland

- List of towns in Northern Ireland

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Boho Heritage Organisation (2009). Edel Bannon, Louise Mclaughlin, Cecilia Flanagan, eds. Boho Heritage: A treasure trove of history and lore. Nicholson & Bass Ltd, Mallusk, Northern Ireland. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-9560607-0-9.

- ↑ Placenames Database of Ireland

- ↑ "Boho Caves". Museum of Learning.

- 1 2 Discoverer 17 (Map) (2003 ed.). Ordnance Survey Northern Ireland (OSNI).

- 1 2 3 4 Jones, Gareth Ll.; Burns, Gaby; Fogg, Tim; Kelly, John (1997). The Caves of Fermanagh and Cavan (2nd Ed.). Lough Nilly Press. ISBN 0-9531602-0-3.

- ↑ Joyce, Patrick Weston (1898). The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places. Longmans, Green and Co. p. 305. ISBN 0-946130-11-6.

- ↑ "Onomasticon Goedelicum locorum et tribuum Hiberniae et Scotiae". University College Cork Documents of Ireland. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- 1 2 "Scheduled Historic Monuments" (PDF). Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-05. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Plunkett, Thomas (1880). "On an Ancient Settlement found about Twenty-one Feet below the Surface of the Peat in the Coal-bog near Boho, Co. Fermanagh". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 2. Dublin. II: 66–70. JSTOR 20651496.

- ↑ Murray, J (1880). "50th Annual Meeting of British Association for the Advancement of Science". Harvard University. p. 236.

- ↑ George Coffey (1953). "On a Cairn Excavated by Thomas Plunkett, M.R.I.A., on Belmore Mountain, Co. Fermanagh". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Royal Irish Academy. 4, (1896 - 1898): 659–666. JSTOR 20490529.

- ↑ Coffey, George (1901). "Irish Copper Celts". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 31: 265–279. doi:10.2307/2842803. JSTOR 2842803.

- ↑ Proudfoot, E. V. B. (1953). "A rath at Boho, Fermanagh". Ulster Journal of Archaeology. 16: 41–57.

- ↑ Stalley, Roger (2002). Wallace, Patrick F.; Ó Floinn, Raghnall, eds. Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland. Irish Antiquities. Gill and Macmillan (in association with The Boyne Valley Honey Company). p. 315. ISBN 0-7171-2829-6.

- ↑ Wood-Martin, William Gregory (1895). "Pagan Ireland; an Archaeological Sketch: A Handbook of Irish Pre-Christian Antiquities". Longmans, Green, and Co: 689.

- ↑ "Ptolemy's Ireland". Ireland's History in Maps. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1 2 3 "The briefne region, connaught series".

- ↑ Egan, Terry, ed. (2006). Bréifne. The Stationery Office Ltd. ISBN 0-337-08747-4.

- ↑ "Placenames NI".

- ↑ "The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee".

- ↑ "The Topographical Poems of John O'Dubhagain and Giolla Na Naomh O'Huidhrin".

- ↑ "The Letters of John O' Donovan". Archived from the original on 28 July 2010.

- ↑ John O'Hart. "Principal Families of Ulster: in Fermanagh". Irish Pedigrees; or, the Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- 1 2 Annals of Loch Cé A.D. 1014 1590. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Trimble, William Copeland (1919). The History of Enniskillen with reference to some manors in Co. Fermanagh, and other local subjects (1919) (5 ed.). Enniskillen: W. Trimble.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dinneen, P. S. (1917). Me Guidhir Fhearmanach, the Maguires of Fermanagh .i. Maghnus agus Giolla Iosa, "dhá mhac Dhuinn Mhoir mic Raghnaill". M.H. Gill. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- ↑ O'Donovan, John, ed. (1862). The Topographical Poems of John O'Dubhagain and Giolla Na Naomh O'Huidhrin. i. Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society Dublin.

- ↑ "The Three Collas and the Kingdom of Airghialla (Oriel)". Ireland's History in Maps. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ O'Hart, John (1892). Irish Pedigrees; or, the Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation (5 ed.). Duffy. ISBN 1-112-18998-X.

- ↑ Unknown. Pádraig Bambury, Stephen Beechinor, eds. Annals of Ulster, Part 106.

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters, Part 12. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Unknown. Pádraig Bambury, Stephen Beechinor, eds. Annals of Ulster, Part 110. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters, Part 13. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ O'Clery, Michael (1575–1643); O'Clery, Cucogry (d. 1664); O'Mulconry, Ferfeasa (fl. 1636); O'Duigenan, Cucogry (fl. 1636); O'Clery, Conary (fl. 1636); O'Donovan, John (1809–1861) (c. 1861). Annala Rioghachta Éireann: Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland Volumes 5 and 6, History To 1603. Hodges, Smith.

- ↑ Unknown. Pádraig Bambury, Stephen Beechinor, eds. Annals of Ulster.

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters, Part 2. ISBN 0-940134-14-4. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Patent Rolls of James I p. 383 Pat. 16 James I (XXXI). 1610. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- 1 2 The Fermanagh Story: a documented history of the County Fermanagh from the earliest times to the present day - Enniskillen: Cumann Seanchais Chlochair, 1969

- 1 2 3 A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. i. S. Lewis & Co. 1837.

- 1 2 Burns, G., ed. (2006). "Boho Heritage Map". Welcome to Boho. Boho Heritage Organisation.

- ↑ "List of townlands in Boho Parish". Public Records Office of Northern Ireland. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ↑ "History: 1608–1862". Portora Royal School. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Sammon, Patrick. "Oscar Wilde and Greece: Notes". The OSCHOLARS Library. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Crawford, Henry S. (1907). "A Descriptive List of Early Irish Crosses". Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 37: 197. Retrieved 2010-11-04.

- 1 2 Donnelly, Colm; MacDonald, Philip; Murphy, Eileen; Beer, Nicholas (2003; pub. 2005). "Excavations at Boho High Cross, Toneel North, County Fermanagh". Ulster Journal of Archaeology. 62: 121–42. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 Donnelly, Colm; MacDonald, Philip; Murphy, Eileen; Beer, Nicholas (2002). "Excavations at Boho High Cross" (PDF). School of Archaeology and Palaeoecology, Queen's University, Belfast. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 2010-11-04.

- 1 2 3 "High Cross at Boho". Documents of Ireland. University College Cork. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ↑ Wood-Martin, William Gregory (1902). Traces of the Elder Faiths of Ireland: A Folklore Sketch; a Handbook of Irish Pre-Christian Traditions. 2. Longmans, Green and Co. p. 247.

- 1 2 3 Blennerhassett, Rev. Canon James (1929). "Clogher clergy and parishes microform: being an account of the clergy of the Church of Ireland in the Diocese of Clogher from the earliest period with historical notices of the several parishes churches etc". Kilsaran Rectory, Castlebellingham.

- ↑ "Scheduled Monumnets Blue List" (PDF). Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2015.

- ↑ Andrew Halpin; Conor Newman (2006). Ireland: an Oxford archaeological guide to sites from earliest times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-280671-0.

- ↑ "The Irish Quaternary Studies Online Project". IRQUAS. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ↑ "N Ireland – Longest caves". UK Caves. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Davies, O. (1939). "Excavation of a horned cairn at Aghanaglack, Co. Fermanagh". Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 69: 21–38.

- ↑ "Boho Heritage Sites". Discover Briefne. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- 1 2 3 "Area of Special Scientific Interest". Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- 1 2 North West Ulster: The Counties of London Derry, Donegal, Fermanagh and Tyrone. Yale University Press. 1979. p. 564.

- 1 2 3 4 "Clones Graveyard Document". Rootsweb Ancestry. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Flanagan, Wm.J. "Fermanagh Area Churches & Graveyards" (XLS). Vignette Sage Database. Sage, Vynette. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ↑ "Animal health and welfare in the Burren" (PDF). Vets Workshop, 13 September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Armstrong, Jayne. "Flower Rich Hay Meadows Flourish in Fermanagh". Countryside Management Branch, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ McFetridge, Jeanelle. "Fermanagh – first class hay meadows". Countryside Management Branch, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Critchley, C. N. R; Burke, M. J. W; Stevens, D. P. (2004). "Conservation of lowland semi-natural grasslands in the UK: a review of botanical monitoring results from agri-environment schemes". Biological Conservation. 115 (3): 263–278. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00146-0. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Evans, E. Estyn (2001). Irish Folk Ways. Courier Dover Publications. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-486-41440-9.

- ↑ Haggerty, Bridget. "Irish culture and customs". Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- 1 2 3 4 "Earth Science Conservation Review". National Museums Northern Ireland.

- 1 2 3 "The Knockmore Scarpland Geodiversity Profile". Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ↑ Martel, E.-A. (1897). Irlande et cavernes anglaises (in French). Paris: Delagrave.

- ↑ "Belmore, Ballintempo & Tullybrack Uplands; Boho". Earth Science Conservation Review. Habitas. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- 1 2 3 "Belmore, Ballintempo & Tullybrack Uplands; Noon's Hole-Arch Cave". Earth Science Conservation Review. National Museums Northern Ireland. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Lough Nacloyduff". Placenames database of Ireland.

- ↑ "Lough Acrottan". Placenames database of Ireland.

- ↑ Wakeman, William F. (1870). Lough Erne, Enniskillen, Belleek, Ballyshannon, and Bundoran: with Routes from Dublin to Enniskillen and Bundoran, by Rail or Steamboat. Dublin: Mullany, John. p. 125. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ↑ "Fermanagh suffers worst ever flooding". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 2009-11-24.

- ↑ Fermanagh Herald; Austin Lynch (10 November 2009). "Residents fear flooding will..". North West of Ireland Printing and Publishing Company. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ↑ "West Fermanagh Scarplands ASSI". Northern Ireland Environment Agency.

- ↑ "Boho ASSI". Northern Ireland Environment Agency.

- ↑ "West Fermanagh Scarplands SAC". Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- ↑ "Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty". Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 15 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Calcareous Grassland". Northern Ireland Countryside Survey 2000. University of Ulster. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Habitat Action Plan Calcareous Grassland". Department of the Environment (Northern Ireland).

- ↑ "Marble Arch Caves & Cuilcagh Mountain Park". European Geoparks Network. Archived from the original on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ↑ "Geopark News: the Worlds First International Geopark!". Fermanagh District Council. 2008. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- ↑ "Dry Bog". Northern Ireland Countryside Survey 2000. University of Ulster. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ Cooper, A.; McCann, T.; Meharg, M. J. (2003). "Sampling Broad Habitat change to assess biodiversity conservation action in Northern Ireland" (PDF). Journal of Environmental Management. 67 (3): 283–290. doi:10.1016/S0301-4797(02)00180-9. PMID 12667477.

- ↑ Cooper, A.; McCann, T. (November 2000). "The Northern Ireland Countryside Survey 2000 – Summary Report on Broad Habitats" (PDF). Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ "Euphrasia salisburgensis – Irish Eyebright". Northern Ireland's Priority Species. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ "Pseudorchis albida – small-white orchid". Northern Ireland's Priority Species. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ "Sisyrinchium bermudiana – Blue-eyed grass". Northern Ireland's Priority Species. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ "Epipactis phyllanthes – green-flowered helleborine". Northern Ireland's Priority Species. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ "Erica vagans – Cornish Heath". Northern Ireland's Priority Species. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ "Monotropa hypopitys – Yellow Bird's-nest". Northern Ireland's Priority Species. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, J. W. (1962). "Calypogeia suecica (Arn. & Pers.) K. Mull. Growing on peat". Irish Naturalists' Journal. 14 (18).

- ↑ "Ophrys apifera Hudson – Bee orchid". Flora of Northern Ireland. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ "Dryas octopetala L. – Mountain Avens". Flora of Northern Ireland. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ "Epipactis palustris (L.) Crantz. – Marsh Helleborine". Flora of Northern Ireland. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ↑ "Neottia nidus-avis (L.) Rich. – Bird's-Nest Orchid". Flora of Northern Ireland. National Museums Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- 1 2 Stone, R. (1998). "Breeding bird survey (Environment and Heritage Service Research and Development Series)".

- ↑ "The Knockmore Scarpland Biodiversity Profile". Northern Ireland Environment Agency.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland's Priority Species: Daubeton's Bat". Habitas. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Burns, S. (1999). "Breeding bird survey (Environment and Heritage Service Research and Development Series)".

- ↑ Scharff, R. F. (1918). "The Irish Red Deer". The Irish Naturalist. Royal Zoological Society of Ireland. Oct–Nov: 133–139. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- 1 2 Glassie, Henry H. (1995). Passing the time in Ballymenone: culture and history of an Ulster community. Indiana University Press. p. 806. ISBN 978-0-253-20987-0.

- ↑ "Irish Fairies: Changelings". Hidden Ireland. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ McGraw, Jim. "Melodious Accord". Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Your Area: Derrygonnelly". Culture Northern Ireland. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ "Boho, Bari, Somalia". Traveling Luck. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ "Ras Boho". Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ "Uadi Boho". Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ "Boho, Leyte, Philippines". Traveling Luck. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ "Boho Australia". Retrieved 2009-03-17.

Further reading

- Elliott, David R. (ed.). Births, Baptisms, Marriages and Burials in Boho Parish, Church of Ireland, County Fermanagh (1840–1879) – Irish Genealogy Series. ISBN 978-0-9781764-2-6.

- Bannon, Edel; McLaughlin, Louise; Flanagan, Cecilia, eds. (November 2008). Boho Heritage: A Treasure Trove of History and Lore. Boho Heritage Organisation. ISBN 978-0-9560607-0-9.

Boho Heritage book

A local group of historians who formed The Boho Heritage Organisation in 2004, launched a book about the area on 17 April 2009. It features over 250 pages and 500 pictures of Boho and is entitled Boho Heritage: A Treasure Trove of History and Lore. This book is available for a limited time from the Linnet Stores, next to The Linnet Inn.

External links

![]() Media related to Boho, County Fermanagh at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Boho, County Fermanagh at Wikimedia Commons

- Public Records Office of Northern Ireland: List of townlands in Boho Parish

- Discover Breifne: Boho Heritage Sites

- Northern Ireland Environment Agency: The Knockmore Scarpland

- Shadows and Stone: Reyfad, Co. Fermanagh photo gallery