Bombing of Braunschweig (October 1944)

.jpg)

During World War II Braunschweig (known as Brunswick in English) was attacked by Allied aircraft in 42 bombing raids.

The attack on the night of 14/15 October 1944 by No. 5 Group Royal Air Force (RAF) marked the high point of the destruction of Henry the Lion's city in the Second World War(WW2). The air raid, part of Operation Hurricane to demonstrate the Allied bombing campaign's capabilities, caused a large fire or conflagration, that may have developed into a firestorm, which resulted in Braunschweig burning continuously for two and a half days from 15th of October to the 17th. Moreover, the attack destroyed Braunschweig's mediaeval city centre (more than 90% of it) thereby changing the city's appearance right down to the present day.

Raids

The RAF first bombed Braunschweig on 17 August 1940, killing 7 people,[1] and the 94th BG earned a Distinguished Service Cross for an 11 January 1944 mission against the MIAG bomber components factory. As part of the Combined Bomber Offensive, Braunschweig was a regular target for RAF (nighttime raids) and American bombers (daylight), including two "Big Week" attacks on 20 and 21 February 1944.

The first major British raid against Braunschweig was on 14/15 January 1944 when nearly 500 Lancasters attacked but faced a strong defence by German fighters. As a relatively small target, most of the bombing missed the city.[2]

In an experimental raid on to see if bombing by radar alone (without target marking) was effective, nearly 400 heavy bombers were sent on 12/13 August 1944. There was no effective concentration of the bombs and nearby towns were bombed by mistake.[3]

Between these dates there were occasions when fast Mosquito bombers were sent on nuisance raids and diversions against Braunschweig.

On October 14, 1944, No. 106 Squadron RAF bombed Brunswick,[4] and one of the last attacks was an attack on chemical plant in March 1945 as part of the campaign against synthetic oil production.[5]

Braunschweig in 1944

Braunschweig was subjected to 42 World War II air raids, and the city was ringed by anti-aircraft guns.. In January 1944 Bomber Commands raids against "Stettin, Brunswick and Magdeburg" were taking 7.2% losses - more than in raids against Berlin that month.[6] The targets included machine and munitions works, the harbour, research institutions, canneries, railway stations and the railway maintenance works, and the German Research Centre for Aviation. Nearby targets included the Reichswerke Hermann Göring in Salzgitter and the KdF-Stadt Volkswagen factory near Fallersleben. The nearby Oflag 79 prisoner-of-war camp was attacked on 24 August 1944.

Preparation for the 15 October 1944 air raid

Raid's purpose

On 13 October, the RAF received orders to carry out Operation Hurricane. The purpose of this action was to demonstrate the Allied bomber forces' destructive might, and to make clear Allied air superiority. The orders included the following:

- "In order to demonstrate to the enemy in Germany generally the overwhelming superiority of the Allied Air Forces in this theatre … the intention is to apply within the shortest practical period the maximum effort of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command and the 8th United States Bomber Command against objectives in the densely populated Ruhr."[7]

Operation Hurricane foresaw Duisburg as its main goal for the RAF's thousand or so bombers, and Cologne for the USAAF's 1,200 or so bombers. A further 233 RAF bombers were detailed for Braunschweig, which in October 1944 had about 150,000 inhabitants.

The planning for the attack on Braunschweig was finalized as of 15 August 1944. Darmstadt had been attacked on the night of 11 September 1944 using a new targeting technique, fan-shaped flying formation, staggering of explosive and incendiary bombs. A largely unprepared town, the resulting fires caused about 11,500 deaths. The Allies now turned their attention to Braunschweig.

Braunschweig was to be largely destroyed not only as an important centre of the armament industry, but also, and above all, as a living place, thereby making it uninhabitable and useless. The goal, namely the greatest possible destruction, was to be reached through detailed attack plans and careful execution thereof, and also using the attributes of the materiel that was to be deployed. The means whereby the goal was to be reached would be the aforesaid firestorm, whose production was no accident; it was scientifically based [8] and developed through painstakingly detailed work.

On 13 October, the chief meteorologist at RAF High Wycombe advised RAF Bomber Command Headquarters of the weather forecast for the weekend of 14–15 October: Slight cloudiness, good visibility throughout the night, moderate winds. The next day, Air Marshal Arthur "Bomber" Harris issued the orders to carry out the attack on Braunschweig and other cities. Brunswick was codenamed Skate by RAF Bomber Command, all German cities being given names of fish, the person responsible for the naming being a keen angler. Actual city names were never used in operational orders for security reasons.

RAF Bomber Command had sought four times in vain during 1944 to inflict lasting destruction upon Braunschweig, failing each time as a result of, among other things, bad weather and strong defences.

On Saturday 14 October 1944 at No. 5 Group's headquarters at Morton Hall, the preparations for the attack were finalized.

October 1944 raid

The raid coincided with a British thousand-bomber raid on Duisburg, the second on that city within 24 hours, a previous British attach having been made by daylight.

According to plan, the aircraft of No. 5 Group took off around 2300 hours local time on 14 October.[9] The main force of the group was 233 four-engined heavy bombers – Avro Lancasters Mark I and III – each with a bomb load of about six tonnes. The Lancasters were accompanied by seven de Havilland Mosquito fast light bombers. The bombers bound for Braunschweig took a course that ran to the south to avoid the Ruhr area, which was heavily defended by anti-aircraft batteries and aircraft. Near Paderborn it turned towards the north, overflew Hanover, and went on to Braunschweig.

As was usual, the British activities for the night included a number of sorties to deceive the German defences about the true targets for the night. One hundred and forty-one training craft flew simulated attacks on Heligoland, 20 Mosquitos went to Hamburg, eight to Mannheim, 16 to Berlin and two to Düsseldorf. They were supported, 140 special operations aircraft of 100 Group RAF deployed in electronic warfare measures against German nightfighter defences. Strips of tinfoil (codenamed "Window") were scattered into the air in great amounts to jam the German air defence system's radar stations, thereby rendering them very nearly useless on this night. The feint against Mannheim, which German forces expected to be the main target, left the Brunschweig attack unopposed.[10]

The siren signal alerting the city to an air raid was sounded at about 0150 on 15 October.

Target marking

The Mosquitos of 5 Group marked the target for the main force. No. 5 Group had developed its own techniques separate to the Pathfinder Force and was using "sector bombing". It used the cathedral as a reckoning point for the "master bomber" in the lead plane. Over the Dom-Insel – the site of Braunschweig Cathedral – a green flare was dropped, a so-called "blind marker". Other Mosquitos dropped their markers of various colours, lighting the target up. Southwest of the downtown core fell the first red flare. These craft in turn gave forth about 60 flares from a height of 1 000 m, which then slowly floated down to the ground, each burning for about 3 to 7 minutes. These lit markers were called "Christmas tree" by the Germans for their characteristic appearance. Given the clear night,[11] the problem-free overflight, the flawless marking of the target, the conditions for this attack were, from the British point of view, optimal.

The green marker on the Dom-Insel served to guide the bomb aimers in all following aircraft, who flew in over it from various directions in a fan-shaped formation, whereupon they dropped their bombs.

RAF filming

This raid on Braunschweig was filmed by a Lancaster of the RAF Film Production Unit outfitted for the task with three "Eyemo"-type cameras. It flew along with the rest at a height of 4,950 m (16,240 ft) over Braunschweig at 260 km/h (160 mph). The time of the attack's onset was noted as 0233 hours. A copy of the film is held by the Städtisches Museum Braunschweig.

The film is provided with the following informational text: "Bomber Command … made a heavy and concentrated attack on the industrial town of Brunswick, which is one of Germany’s biggest centres for the aircraft and engineering industries. As the aircraft with the cameras runs up to the target the fires can be seen spreading rapidly all over the city and by the time the aircraft is over the target the whole city is ablaze and the streets can been seen clearly outlined."

The firestorm

Before long, about 847 tonnes of bombs had been dropped on the city, first about 12,000 explosive bombs – the so-called "Blockbusters" – in many "carpets" on the old timber-frame town to get the intended firestorm started in the most efficient way – with the old town's wooden houses. The blast waves blew the houses' roofs off, exposing the insides, blew windowpanes out, splintered the inner structure, broke walls down, tore electricity and water supplies up, and drove firefighters and rescue service personnel, as well as damage observers into cellars and bunkers.

After the wave of explosive bombs came about 200,000 phosphorus and incendiary bombs whose job was to ignite the firestorm, for as with attacks on other cities, for instance Hamburg (Operation Gomorrah), the firestorm was no accident, but rather a carefully planned tactic that was the result of years of thorough scientific research. It would still be burning long after the bombers had returned to England.

By about 0310 hours, about 40 minutes after the first explosive bombs had been dropped on Braunschweig, the RAF bombing was over.

The hot masses of air were sucked upwards by the powerful thermal that arose from the conflagration. Cooler air was thereby brought down from great heights, making the local weather much like a windstorm with constantly changing winds that only worsened the fires, thereby further strengthening the winds, which were actually strong enough to sweep small pieces of furniture up and toss people about.

About three and a half hours later, towards 6:30 in the morning, the firestorm reached its peak in the downtown core. About 150 ha of historic old Braunschweig was going up in flames. The city's tallest church steeples – those of St. Andrew’s at about 100 m tall – could be seen burning far beyond the town, and they also rained embers down over the whole city. Streets, buildings and the ruins of the downtown core were heavily littered with incendiary bombs, greatly slowing rescue vehicles and fire engines, which had to fight their way through this and many other dangers in the firestorm to reach into the fire.

The city burnt so intensely and brightly that the light from the fire could be seen far and wide. From all directions, helpers and firefighters thronged into the burning town to help. They came from, among other places, Hanover to the west and Helmstedt in the east, from Celle to the north and Quedlinburg to the south.

Within the 24 hours of Operation Hurricane, the RAF dropped about 10,000 tonnes of bombs in total on Duisburg and Braunschweig, the greatest bomb load dropped on any single day in the Second World War.

Rescue of 23,000 trapped people

The many fires in the city centre quickly grew together into one widespread conflagration. However, in this area were six large bunkers and two air raid shelters, all quite overfull, in which 23,000 people had sought refuge from the attack. While these thousands waited in seeming safety inside their thick-walled shelters for the all-clear signal, outside the firestorm raged.

The fire brigade very soon realized the threat to these 23,000 trapped people – the fire was growing ever hotter, and the oxygen in the bunkers and shelters thereby ever thinner. The danger was clearly that the victims would either suffocate for lack of oxygen if they stayed in the bunkers, or be burnt alive if they tried to leave and escape through the firestorm outside.

Die Wassergasse ("water alley")

Towards 5 o'clock in the morning, before the firestorm had reached its full intensity, the idea of building a "water alley" was conceived by Lieutenant of the Fire Brigade Rudolf Prescher. This "water alley" would allow the trapped people to flee their shelters for safe areas of the city.

The water alley consisted of a long hose that had to be kept under a constant water mist to shield it against the fire's tremendous heat as the firefighters led the hose through to the shelters where the people were trapped. The reach of each of the little jets issuing from the holes in the hose overlapped each other making a continuous, artificial "rain zone".

The bunkers were reached towards 7 o'clock Sunday morning, after the fire storm had reached its greatest intensity. All the trapped people were still alive, but had no idea what lay outside for them. All 23,000 managed to get out of the danger zone and reach safe areas, such as the museum park. Only at the Schöppenstedter Straße 31 air shelter did the help come too late, where 95 of the 104 people had suffocated by the time the fire brigade reached them. The firestorm had been so intense in this particular part of the city that it had used up nearly all the oxygen, making it impossible to save more than nine people.

Effects

A great part of Braunschweig's tightly packed city centre was made up of about 800 timber-frame houses, many of which dated back to the Middle Ages. There were also stone buildings dating mainly from the 17th and 18th centuries. The old cathedral, which the RAF had used as a reckoning point for the whole operation, and which the Nazis had turned into a "National Shrine" in 1935, was left standing. Many important historic buildings were largely or utterly destroyed.

| Building | time built | Condition after 15 October 1944 |

| Aegidienkirche (church) | 13th-15th centuries | heavily damaged |

| Alte Waage | 1534 | utterly destroyed, from 1990 - 1994 rebuilt |

| Andreas-Kirche (church) | about 1230 | heavily damaged |

| Bierbaumsches Haus | 1523 | destroyed |

| Braunschweiger Schloss (Palace) | 1833–1841 | heavily damaged, demolished in 1960 amid great controversy; reconstructed and reopened 2008. Now houses city library and joined with the new Schloss-Arkaden mall. |

| Brüdern-Kirche (church) | about 1361 | heavily damaged |

| Dankwarderode Castle | 1887–1906 | heavily damaged |

| Gewandhaus (cloth hall) | before 1268 | heavily damaged |

| Hagenmarkt-Apotheke | 1677 | destroyed |

| Haus Salve Hospes | 1805 | heavily damaged |

| Katharinen-Kirche (church) | about 1200 | heavily damaged |

| Liberei | 1412–1422 | heavily damaged |

| Magnikirche (church) | about 1031 | heavily damaged |

| Martineum | 1415 | destroyed |

| Martini-Kirche (church) | about 1195 | heavily damaged |

| Meinhardshof | about 1320 | destroyed |

| Mumme-Haus (brewery) | 16th century | destroyed |

| Nicolai-Kirche (church) | 1710–1712 | destroyed |

| Pauli-Kirche (church) | 1901/06 | heavily damaged |

| Petri-Kirche (church) | before 1195 | heavily damaged |

| Stechinelli-Haus | 1690 | heavily damaged |

| Staatstheater | 1861 | heavily damaged |

On the next morning, 16 October, Braunschweig lay under a thick cloud of smoke. A British reconnaissance aircraft sent to take photographs of the bombing's aftermath for analysis had to return to England, as its mission had been rendered impossible by the opaque pall that hung over the town.

By the evening of 17 October, the last of the fire's main hotspots had been put out, but it took another three days to quench lesser fires, until 20 October. Eighty thousand of the townsfolk were left homeless by the attack.

The destruction was so widespread and thorough that ordinary people and the experts alike, even years after the war, were convinced that the attack had come from one of the dread "thousand-bomber attacks", such as the one that had laid Cologne waste. The extent of the damage could seemingly not otherwise be explained. Only after the British opened their military archives did it become plain that it had been "only" 233 bombers.

Casualties

The exact number of victims of the 15 October attack is unknown. The given figures range from 484 to 640 dead, 95 of those by suffocation at the Schöppenstedter Straße 31 shelter alone. Nowadays, historians put the number at more than a thousand.

These "light" losses – compared with those suffered in the great air raids on Dresden, Hamburg, Pforzheim and other German cities – according to expert opinions stem from various factors. For one thing, Braunschweig lay on the direct flight path, that is, the "lane" leading to Magdeburg and Berlin, and right near the armament industry centres of Salzgitter (Hermann-Göring-Werke) and Wolfsburg (Volkswagen Works), meaning that Braunschweigers were used to – even in a sense "trained for" – quickly responding to alarms (there were 2,040 warnings and 620 air raid alarms between 1939 and 1945). This may have prepared them for the attack, even though many of the earlier attacks from which they had sought shelter actually targeted the other cities mentioned. Furthermore, the city also had at its disposal a great number of the latest type of air raid bunkers and blockhouses known as Hochbunkers . Lastly, the fire brigade's "water alley" alone saved 23,000 people's lives.

The RAF lost a single Lancaster bomber to anti-aircraft fire that night.

Bunkers in Braunschweig

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Braunschweig Armour

Braunschweig had, compared to other German cities, a great number of the most modern air raid bunkers, some of which were Hochbunkers (high-rise bunkers), which nevertheless suffered from regular overcrowding as the war wore on. As modern and robust as they were, the fact is that the so-called Braunschweig Armour was developed at the Institute for Building Materials, Massive Construction and Fire Protection of the Technical University of Braunschweig. It became a kind of safety standard for building air raid bunkers throughout the Reich.

| Year built | Location | Places | Remarks | |

| 1 | 1940 | Alte Kochenhauerstraße | 813 | still standing, on synagogue property |

| 2 | 1940/41 | Alte Waage | 220 | still standing |

| 3 | 1941/42 | Bockstwete | 750 | still standing, altered |

| 4 | 1941/42 | Borsigstraße/Bebelhof | 800 | torn down |

| 5 | ? | Kaiserstraße | 642 | still standing |

| 6 | ? | Kalenwall (old railway station) | 428 | still standing, altered |

| 7 | 1941/42 | Kralenriede | 500 | still standing |

| 8 | 1941/42 | Ludwigstraße | 236 | still standing |

| 9 | 1941/42 | Madamenweg | 1,500 | still standing, altered for use as flats |

| 10 | ab 1942 | Glogaustraße in Melverode | 350 | still standing |

| 11 | 1941/42 | Methfesselstraße | 1,250 | still standing, altered |

| 12 | 1941/42 | Münzstraße (Polizei) | 450 | still standing |

| 13 | 1940/41 | Okerstraße | 944 | still standing, altered for use as flats |

| 14 | 1944 | Ritterstraße | 840 | still standing, altered for use as flats |

| 15 | 1940/41 | Auerstraße in Rühme | 650 | torn down |

| 16 | 1940/41 | Sack | 700 | still standing, altered |

| 17 | 1940/41 | Salzdahlumer Straße | 986 | still standing, altered |

| 18 | ? | Stollen im Nussberg | 10,000 | demolished with explosives |

| 19 | ? | Stollen im Windmühlenberg | 1,000 | eliminated |

Fire brigades from Braunschweig and other cities deployed against the firestorm

According to estimates, especially during the night of the bombing as well as in the next six days until the last fires were put out, about 4,500 firefighters were deployed. They came from up to 90 km (56 mi) away, and included not only members of city fire brigades from, among other places, Blankenburg, Celle, Gifhorn, Hanover, Helmstedt, Hildesheim, Peine, Salzgitter, Wernigerode and Wolfenbüttel, but also volunteers and members of plant fire brigades at the various factories in Braunschweig and the surrounding area. Due to their efforts the city was not utterly burnt that night.

Aftermath

The bombing in the Nazi press

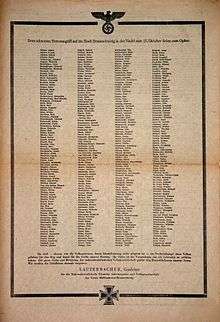

Even on the night of the attack, the National Socialists seized the opportunity to make the victims an instrument in their quest for total war, for already by the next day, 16 October, with Braunschweig still burning, the local Nazi propaganda newspaper, the Braunschweiger Tageszeitung, came out with the headline "Die teuflische Fratze des Gegners. Schwerer Terrorangriff auf Braunschweig – Volksgemeinschaft in der Bewährung" ("The foe's devilish antics. Heavy terror attack on Braunschweig – Population put to the test"), and Südhannover-Braunschweig Gauleiter Hartmann Lauterbacher's (1909–1988) pithy words of perseverance to "the Braunschweigers". On 19 October, the number of "fallen" was given as 405, and on 20 October appeared a full-page death notice with 344 names. On 22 October, one week after the disastrous attack, there was a "memorial act" for the victims, both at the State Cathedral ("Staatsdom") – as the Nazis called Braunschweig's cathedral – and at the Schlossplatz, the square in front of Braunschweig Palace.

The same night, Braunschweig had another heavy air raid. This time the bombers were USAAF Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses. The last air raid on Braunschweig came on the morning of 31 March 1945, carried out by the 392d Bombardment Group. Their main target was the East Railway Station.

Statistics of destruction

Population

When the Second World War began, Braunschweig had 202,284 inhabitants. By the war's end, the population had fallen by 26.03% to 149,641. From the effects of war (mainly air raids but also their aftermath, such as having to dispose of or otherwise make safe the duds that the Allies dropped) about 2,905 people died, 1,286 of whom (44.3%) were foreigners. These foreigners were predominantly prisoners of war, forced labourers, and concentration camp inmates who worked in the armament industry, and who were forbidden access to the air raid bunkers.

Destruction of housing and infrastructure

Between 1940 and 1945, Braunschweig was targeted 42 times by RAF and USAAF air raids.

Exact figures are available only for destroyed houses and flats. By the time the war was over, about 20% of Braunschweig's dwellings had been left completely undamaged, but about 24% of them had been utterly destroyed. The remaining 55% were somewhat damaged, with the extent of damage to any particular dwelling varying greatly with others. In 1943, before the area bombing of Braunschweig, there were 15,897 houses in the city, but by mid-1945, only 2,834 (about 18%) were left undamaged. The city also had 59,826 flats, of which 11,153 (about 19%) were still undamaged by the time the war ended. The level of destruction with regard to residential buildings stood at 35%, leading to homelessness for almost 80% of the townsfolk by war's end. Sixty percent of the city's places of cultural interest, including the municipal buildings, were likewise destroyed, along with about 50% of its industrial areas.

Overall destruction rate and amount of rubble

The destruction rate in Braunschweig's downtown core (within the "Oker Ring", the Oker being a river that encircles Braunschweig) stood at about 90%, and the overall figure for Braunschweig as a whole was 42%. The attack on the city produced an estimated 3 670 500 m³ of rubble. These figures put Braunschweig among Germany's most heavily damaged cities in the Second World War.

After the war

Reconstruction

On 17 June 1946, the rubble clearing officially began in Braunschweig. The job took 17 years, with the city only officially declaring the task accomplished in 1963. Actually, however, smaller messes were still being cleared up years after that.

Braunschweig's reconstruction in the 1950s and 1960s proceeded very quickly, as housing was so badly needed, and the city's infrastructure needed to be built all over again. Since the downtown core was a rubble-strewn wasteland, city and spatial planners seized the chance to build a new, modern, and above all car-friendly city, an idea promoted by Hans Bernhard Reichow. This once again led in many places to further destruction (through new roadways, for instance) and the removal of city scenery that had become historic, since in part the former city layout was ignored. Ruins were hastily torn down instead of being restored, and the car was raised as the new "yardstick" whereby the "new" Braunschweig was to be measured. Thus was wrought, especially in the downtown core, a "second destruction" of Braunschweig.

The later destruction of historic buildings and cultural sites, such as the demolition of many medieval, baroque and classical buildings or the controversial demolition of the damaged Braunschweiger Schloss (palatial residence) in 1960 led much as with the Dresden Frauenkirche, the Berliner Stadtschloss (Berlin City Palace) and other prominent buildings in other cities to a further loss of identity for the local people, and was the cause of much controversy for decades.

Reconstruction of damaged or destroyed buildings continues in part down to the present day, as can be seen in the partial reconstruction of the Braunschweiger Schloss.

Memorials

Meaning and necessity of the destruction

Already in 1943, the Anglican Bishop and Member of the House of Lords George Bell was putting forth the view that such attacks as these threatened the ethical foundations of Western civilization and destroyed any chance of future reconciliation between the former foes.

Since the end of World War II, the question has been raised as to whether the destruction of Braunschweig in October 1944 was still a military necessity given that the war was into its final phase. This is part of the debate on whether the destruction of other German cities and loss of life that occurred once the Allied strategic bomber forces were released from their tactical support of the Normandy landings and resumed the strategic bombing campaign in September 1944 (a campaign that would last without further interruption until days before the end of World War II in Europe in May 1945,) can be morally justified.[12]

15 October as a fixed point in the city's history

In the Main Cemetery in Braunschweig is a memorial, together with the graves of many victims of the 15 October 1944 raid.

Since the attack, memorial events and exhibitions have been held in Braunschweig every 14–15 October. The events of those two days also echo strongly in local historical literature (see under "References"). On 14–15 October 2004 – the sixtieth anniversary of the destruction of Braunschweig's historic old town – there were once again many events. Among other memorials that took place was Benjamin Britten's War Requiem, conducted at the Braunschweig Cathedral in the presence of British Ambassador Sir Peter Torry

Footnotes

- ↑ "The Battle of Britain (June–October 1940)". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. UK Crown. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- ↑ Campaign Diary January 1944

- ↑ Campaign Diary August 1944

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Hastings, Max Bomber Command p342

- ↑ RAF diary October 1944

- ↑ Jörg Friedrich

- ↑ During the war Britain was on daylight saving time. In the winter time was set to British Summer Time and in the summer to Double Summer Time, so local time and British time were the same

- ↑ Bowman, Legend of the Lancaster p 224

- ↑ the report from filmed intelligence was "Visibility: excellent"

- ↑ A. C. Grayling Among the Dead Cities: Was the Allied Bombing of Civilians in WWII a Necessity or a Crime?, (2006), ISBN 0-7475-7671-8

References

- Braunschweiger Zeitung (publisher): Die Bomben-Nacht. Der Luftkrieg vor 60 Jahren. Braunschweig 2004

- Friedenszentrum Braunschweig e.V. (publisher): Braunschweig im Bombenkrieg. 50 Jahre danach. Den Opfern des Krieges gewidmet. Band 1: Dokumente zur Ausstellung 30.09. – 31.10.1993. Braunschweig 1994

- ibid.: Braunschweig im Bombenkrieg. 50 Jahre danach. Den Opfern des Krieges gewidmet. Band 2: Dokumente von Zeitzeuginnen und Zeitzeugen: „Bomben auf Braunschweig“. Landesmuseum 11.09. – 16.10.1994. Braunschweig 1994

- ibid.: Braunschweig im Bombenkrieg. 50 Jahre danach. Den Opfern des Krieges gewidmet. Band 3: Dokumente aus der Gedenknacht 14./15.10.1994: „Die Gerloff-Berichte“. Braunschweig 1994

- Jörg Friedrich: Der Brand. Deutschland im Bombenkrieg 1940–1945, Munich 2002

- Eckart Grote: Braunschweig im Luftkrieg. Alliierte Film-, Bild- und Einsatzberichte der US-Air Force / British Royal Air Force aus den Jahren 1944/1945 als stadtgeschichtliche Dokumente. Braunschweig 1983

- Eckart Grote: Braunschweig im Zweitem Weltkrieg. Dokumente einer Zerstörung – Stunde Null – Neubeginn In: Arbeitsberichte aus dem Städtischen Museum Braunschweig, Nr. 65; Braunschweig 1994

- Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Luftangriffsziel Braunschweig – Dokumente der Zerstörung. Braunschweig 1994

- Peter Neumann: Braunschweig als Bombenziel. Aus Aufzeichnungen der Jahre 1944 und 1945 In: Braunschweigisches Jahrbuch, Band 65; Braunschweig 1984

- Rudolf Prescher: Der rote Hahn über Braunschweig. Luftschutzmaßnahmen und Luftkriegsereignisse in der Stadt Braunschweig 1927 bis 1945, Braunschweig 1955

- Eckart Schimpf: Nachts, als die Weihnachtsbäume kamen. Eine ganz normale Braunschweiger Kindheit im Chaos von Kriegs- und Nachkriegszeit. Braunschweig 1998

- Hedda Kalshoven: Ich denk’ so viel an Euch. Ein deutsch-niederländischer Briefwechsel 1920–1949. Munich 1995

- "Campaign Diary". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. UK Crown. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- Braunschweig 1945 – Bombardierung, Befreiung, Leben in Trümmern. Remembered and commented on by Eckard Schimpf. Braunschweiger Zeitung und Archiv Verlag, Braunschweig 2005 DVD

- Feuersturm – Der Bombenkrieg gegen Deutschland. DVD-Edition, SPIEGEL TV history. Polar Film Medien GmbH, Gescher 2003

External links

- „Das brennende Braunschweig am 14./15. Oktober 1944“, painting by Walther Hoeck

- Description of bunker, bombs, destruction and more (in German)

- Map of Braunschweig's air raid damage, 1945

- Graveyard for victims of 15 October 1944 at the Main Cemetery in Braunschweig

- "Braunschweig Armour" for bunkers

- British Ambassador Sir Peter Torry's speech on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the destruction of Braunschweig

- Eyewitness account: “All of a sudden, you're in the thick of it, and bombs start raining down on you …” (in German)