Book burning

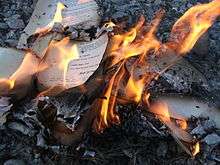

Book burning refers to the ritual destruction by fire of books or other written materials. Usually carried out in a public context, the burning of books represents an element of censorship and usually proceeds from a cultural, religious, or political opposition to the materials in question.[1]

In some cases, the destroyed works are irreplaceable and their burning constitutes a severe loss to cultural heritage. Examples include the obliteration of the Library of Baghdad, the burning of books and burying of scholars under China's Qin Dynasty, the destruction of Aztec codices by Itzcoatl.

In other cases, such as the Nazi book burnings, other copies of the destroyed books survive - but still, the instance of book burning becomes emblematic of a harsh and oppressive regime which is seeking to censor or silence an aspect of a nation's culture.

Book burning can be an act of contempt for the book's contents or author, and the act is intended to draw wider public attention to this opinion. Examples include the burning of Wilhelm Reich's books by the FDA and the 2010 Qur'an-burning controversy.

Art destruction is related to book burning, both because it might have similar cultural, religious, or political connotations, and because in various historical cases books and artworks were destroyed at the same time.

In modern times, other forms of media, such as phonograph records, video tapes, and CDs have also been burned, shredded, or even crushed by a road-roller.

Historical background

The burning of books has a long history as a tool wielded by authorities both secular and religious, in efforts to suppress dissenting or heretical views that are perceived as posing a threat to the prevailing order.

700 BC

According to the Tanakh, in the 7th century BC King Jehoiakim of Judah burned part of a scroll Baruch ben Neriah had written at prophet Jeremiah's dictation (Jeremiah 36).

Burning of books and burying of scholars in China (210 BC)

Qin Shi Huang, first emperor of Qin Dynasty, ordered a Burning of books and burying of scholars in 213 BC and burial alive of 460 Confucian scholars in 210 BC in order to stay in the throne. Some of these books were written in Shang Xiang, a superior school founded in 2208 BC. The event caused the loss of many philosophical treatises of the Hundred Schools of Thought. The official philosophy of government ("legalism") survived.

Christian burnings

After the First Council of Nicea (AD 325), Roman emperor Constantine the Great issued an edict against nontrinitarian Arians which included systematical book burning; "In addition, if any writing composed by Arius should be found, it should be handed over to the flames, so that not only will the wickedness of his teaching be obliterated, but nothing will be left even to remind anyone of him. And I hereby make a public order, that if someone should be discovered to have hidden a writing composed by Arius, and not to have immediately brought it forward and destroyed it by fire, his penalty shall be death. As soon as he is discovered in this offense, he shall be submitted for capital punishment....."[2] According to Elaine Pagels, "In AD 367, Athanasius, the zealous bishop of Alexandria... issued an Easter letter in which he demanded that Egyptian monks destroy all such unacceptable writings, except for those he specifically listed as 'acceptable' even 'canonical' — a list that constitutes the present 'New Testament'".[3] Pagels cites Athanasius's Paschal letter (letter 39) for 367 AD, which prescribes a canon but does not explicitly order monks to destroy excluded works.[4] Heretical texts do not turn up as palimpsests, washed clean and overwritten, as do many texts of Classical antiquity. According to author Rebecca Knuth, multitudes of early Christian texts have been as thoroughly "destroyed" as if they had been publicly burnt.[5]

Burning of Library of Alexandria

Library of Alexandria, the biggest library in ancient world, created in 300 BC and with a collection of more than 9,000 Manuscripts were burned during Roman occupation, possibly by a fire set by Julius Caesar in 48 BC, an attack by Aurelian in the AD 270's, or by the decree of Coptic Pope Theophilus in AD 391.

Nestorian books burning

Activity of Cyril of Alexandria (c. 376–444) brought fire to almost all writings of Nestorius (386-450), shortly after 435.[6]

Arian books burning

According to the Chronicle of Fredegar, Recared, King of the Wisigoths (reigned 586–601) and first Catholic king of Spain, following his conversion to Catholicism in 587, ordered that all Arian books should be collected and burned; and all the books of Arian theology were reduced to ashes, with the house in which they had been purposely collected.[7][8]

Burning of Jewish manuscripts in 1244

In 1244, as an outcome of the Disputation of Paris, twenty-four carriage loads of Talmuds and other Jewish religious manuscripts were set on fire in the streets of Paris.[9] [10]

Burning of Aztec and Mayan manuscripts in 1560's

During the conquest of the Americas and the aftermath of the encounter between European and indigenous American civilizations, many books written by indigenous peoples were destroyed. There were many books written by the Aztecs in existence at the time of the Spanish conquest of Yucatán in the 16th century. However, most were destroyed by the Conquistadors and the Catholic priests, with the exception of Priest Bartolome de la Casas. In particular, many books in Yucatán were ordered destroyed by Bishop Diego de Landa in July 1562. De Landa wrote: "We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they (the Maya) regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction." Ironically, most of the books that were destroyed by the Europeans were biased and based upon the Aztec people's version of the history of the region. The Aztecs too had conquered the area and destroyed much of the Mayan books and documents.

Burning of US Library of Congress

The Library of Congress was founded in 1800, 24 years after the United States gained its independence from England. In 1813, 3,000 books from the Library of Congress were used by the English forces to burn down the US Capitol during the Burning of Washington. Although there were dissenting voices to this wanton destruction, the conflagration was motivated by a strong desire on the part of the English forces to humiliate the Americans.[11]

Institutions dedicated to book burnings

Anthony Comstock's New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, founded in 1873, inscribed book burning on its seal, as a worthy goal to be achieved. Comstock's total accomplishment in a long and influential career is estimated to have been the destruction of some 15 tons of books, 284,000 pounds of plates for printing such 'objectionable' books, and nearly 4,000,000 pictures. All of this material was defined as "lewd" by Comstock's very broad definition of the term — which he and his associates successfully lobbied the United States Congress to incorporate in the Comstock Law.[12]

Nazi regime (1933)

Main: Nazi book burnings

The Nazi government decreed broad grounds for burning material:

...which acts subversively on our future or strikes at the root of German thought, the German home and the driving forces of our people...— The Jewish Virtual Library [13]

Notable book burnings and destruction of libraries

Burnings by authors

In 1588, the exiled English Catholic William Cardinal Allen wrote "An Admonition to the Nobility and People of England", a work sharply attacking Queen Elizabeth I. It was to be published in Spanish-occupied England in the event of the Spanish Armada succeeding in its invasion. Upon the defeat of the Armada, Allen carefully consigned his publication to the fire, and we only know of it through one of Elizabeth's spies, who had stolen a copy.[14]

The Hassidic Rabbi Nachman of Breslov is reported to have written a book which he himself burned in 1808. To this day, his followers mourn "The Burned Book" and seek in their Rabbi's surviving writings for clues as to what the lost volume contained and why it was destroyed.[15]

Carlo Goldoni is known to have burned his first play, a tragedy called Amalasunta, when encountering unfavorable criticism.

Nikolai Gogol burned the second half of his magnum opus Dead Souls, having come under the influence of a priest who persuaded him that his work was sinful; Gogol later described this as a mistake.

After Hector Hugh Munro (better known by the pen name Saki) was killed in World War I in November 1916, his sister Ethel destroyed most of his papers.

Joe Shuster, who together with Jerry Siegel created the fictional superhero Superman, in 1938 burned the first Superman story when under the impression that it would not find a publisher.

Books saved from burning

In Catholic hagiography, Saint Vincent of Saragossa is mentioned as having been offered his life on condition that he consign Scripture to the fire; he refused and was martyred. He is often depicted holding the book which he protected with his life.

Another book-saving Catholic Saint is the Tenth Century St. Wiborada. She is credited with having predicted in 925 a Hungarian invasion of her region in Switzerland. Her warning allowed the priests and religious of St. Gall and St. Magnus to hide their books and wine and escape into caves in nearby hills.[16] Wiborada herself refused to escape and was killed by the marauders, being later canonized. In art, she is commonly represented holding a book to signify the library she saved, and is considered a patron saint of libraries and librarians.

At the beginning of the Battle of Monte Cassino in the World War II, two German officers—Viennese-born Lt.Col. Julius Schlegel (a Roman Catholic), and Captain Maximilian Becker (a Protestant)—had the foresight to transfer the Monte Cassino archives to the Vatican. Otherwise the archives – containing a vast number of documents relating to the 1500-years' history of the Abbey as well as some 1,400 irreplaceable manuscript codices, chiefly patristic and historical – would have been destroyed in the Allied air bombing which almost completely destroyed the Abbey shortly afterwards. Also saved by the two officers' prompt action were the collections of the Keats-Shelley Memorial House in Rome which had been sent to the Abbey for safety in December 1942.

In 1940's France, a group of anti-fascist exiles created a Library of Burned Books which housed all the books that Adolf Hitler had destroyed. This library contained copies of titles that were burned. These book burnings from the Nazis was an idea to help cleanse German culture of Jewish and foreign influences such as pacifist and decadent literature. The Nazis were going to make a "museum" of Judaism once the final solution was complete to house certain books that were saved by the Nazis themselves.[17]

Book burning wills

When Virgil died, he left instructions that his manuscript of the Aeneid was to be burnt, as it was a draft version with uncorrected faults and not a final version for release. However, this instruction was ignored. It is mainly to the Aeneid, published in this "imperfect" form, that Virgil owes his lasting fame – and it is considered one of the great masterpieces of Classical literature as a whole.

Before his death, Franz Kafka wrote to his friend and literary executor Max Brod: "Dearest Max, my last request: Everything I leave behind me... in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others'), sketches, and so on, [is] to be burned unread."[18] Brod overrode Kafka's wishes, believing that Kafka had given these directions to him, specifically, because Kafka knew he would not honour them – Brod had told him as much. Had Brod carried out Kafka's instructions, virtually the whole of Kafka's work – except for a few short stories published in his lifetime – would have been lost forever. Most critics, at the time and up to the present, justify Brod's decision.

A similar case concerns the noted American poet Emily Dickinson, who died in 1886 and left to her sister Lavinia the instruction of burning all her papers. Lavinia Dickinson did burn almost all of her sister's correspondences, but interpreted the will as not including the forty notebooks and loose sheets, all filled with almost 1800 poems; these Lavinia saved and began to publish the poems that year. Had Lavinia Dickinson been more strict in carrying out her sister's will, all but a small handful of Emily Dickinson's poetic work would have been lost.[19][20]

Modern biblioclasm

Biblioclasm still occurs. All over the world schools and libraries have been destroyed in recent years. Despite the act of destroying books being condemned by the majority of society, people still participate on small and large scale.

In Azerbaijan, when a modified Latin alphabet was adopted, books published in Arabic script were burned, especially in the late 1920s and 1930s.[21] The texts were not limited to the Quran; medical and historical manuscripts were also destroyed.[22]

Book burnings were organised regularly in Nazi Germany in the 1930s by stormtroopers to destroy degenerate works, especially by Jewish authors such as Thomas Mann, Marcel Proust & Karl Marx.

In the 1950s, over six tons of books by William Reich were burned in the U.S. under judicial orders.[23]

In Denmark, a comic book burning took place 23 June 1955. It was a bonfire consisting of comic books and on top of that a life size cardboard cutout of The Phantom.[24]

Kjell Ludvik Kvavik, a senior Norwegian official, had a penchant for removing maps and other pages from rare books and was noticed in January 1983 by a young college student. The student, Barbro Andenaes, reported the actions of the senior official to the superintendent of the reading room and then to the head librarian of the university library in Oslo. Hesitant to make public something that would greatly hurt the career of Kvavik even if the accusation proved false, media kept the name of the perpetrator quiet until his house was searched by police. The authorities seized 470 maps and prints as well as 112 books that Kvavik had illegally obtained. While this may not be the large scale, violent demonstration seen during wars, Kvavik's disregard for libraries and books shows that destruction of books on any scale can affect an entire country. Here, a senior official in the Norwegian government was disgraced and the University Library was refunded only a small portion of the costs it incurred from the loss and destruction of rare materials as well as the security changes that had to be made. In this case, the draw of personal profit and enhancing one's own collection was the cause of the defacement of rare books and maps. While the main goal was not destruction for destruction's sake, the resulting damage to the ephemera still carries weight within the library community.[25]

The annihilation of the Bosnian National and University Library in August 1992 was led by Serbian nationalist Ratko Mladic. After firing incendiary shells on the library roof, Sarajevans attempted to save the books from the growing flames. As firefighters arrived to help, the nationalists began shooting bullets into the crowd, killing firefighters and cutting off supplies to stop the fire. As the onslaught continued, Bosnian soldiers continued their rescue efforts. The building burned. The Serbian nationalist purposefully targeted libraries and places of cultural significance in an effort to destroy the diverse history and Ottoman legacy within Bosnia. The nationalists laid waste to libraries, museums, and architectural treasures, and within just the National and University library, approximately 1.5 million volumes were lost, including almost 150,000 rare books.[26]

South Africa in 1984. Amsterdam's South African Institute was infiltrated by an organized group bent on drawing attention to the inequality of the apartheid. Well-organized and ensuring patrons of the library that no harm would come to them, group members systematically smashed microfiche machines and threw books into the nearby waterway. Indiscriminate of the content being destroyed, shelf after shelf was cleared of its contents until the group left. Staff members fished books from the water in hopes of salvaging the rare editions of travel books, documents about the Boer Wars, and contemporary materials both for and against apartheid. Many were destroyed by oil, ink, and paint that the anti-apartheid demonstrators had flung around the library. The world was outraged at the loss of knowledge that these demonstrators had caused, and instead of winning support and getting attention on the issue of apartheid, the international audience cried out against the actions at the Amsterdam's South African Institute. Some demonstrators came forward to explain that they believed the institute was pro-apartheid and that nothing was being done to change the status quo in South Africa.[27]

The advent of the digital age has resulted in an immense collection of written work being catalogued exclusively or primarily in digital form. The intentional deletion or removal of these works has been often referred to as a new form of book burning.[28]

Some supporters have celebrated book burning cases in art and other media. Such is the bas-relief by Giovanni Battista Maini of The Burning of Heretical Books over a side door on the façade of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, which depicts the burning of 'heretical' books as a triumph of righteousness.[29]

In 1973, during the years of the Chilean fascist dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet, hundreds of books were burned as a way of repression and censorship.[30]

Mullumbimby NSW Australia in 2009. Reported as "just like the ritual burning of books in Nazi Germany", a book-burning ceremony was held by students of alleged 'cult' Universal Medicine, an esoteric healing business owned by Serge Benhayon. Students were invited to throw their books onto the pyre. Most of the volumes were on Chinese medicine, kinesiology, acupuncture, homeopathy and other alternative healing modalities, all of which Benhayon has decreed "prana".[31]

In 1981 the Jaffna Public Library in Jaffna, Sri Lanka was burned down by Sinhalese police and paramilitaries during a pogrom against the minority Tamil population. At the time of its burning it contained almost 100,000 Tamil books and rare documents.[32]

Sikh book burning

In the Sikh religion, any copies of their sacred book Guru Granth Sahib which are too badly damaged to be used, and any printer's waste which bears any of its text, are cremated. Such a cremation is called Agan Bhet, and is similar to that performed when cremating a deceased Sikh.[33][34][35][36]

Book burnings in popular culture

In literature

- A much-quoted line in Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita is "manuscripts don't burn" (Russian: рукописи не горят). "The Master", a major protagonist in the book, is a writer who is plagued by both his own mental problems and the oppression of Stalin's regime in 1930s Moscow. He burns his treasured manuscript in an effort to hide it from the Soviet authorities and cleanse his own mind from the troubles the work has brought him. The character Woland (a mysterious magician who is, in fact, Satan) later gives the manuscript back to him, saying, "Didn't you know that manuscripts don't burn?" There is an autobiographical element reflected in the Master's character here, as Bulgakov in fact burned an early copy of The Master and Margarita for much the same reasons.

- The first part of Don Quixote has a scene in which the priest and the housekeeper of the eponymous knight go through the chivalric romances that have turned him mad. In a kind of auto de fe, they burn most of them. The comments of the priest express the literary tastes of the author, though he offers some sharp criticisms of Cervantes's works as well. It is notable that he saves Tirant lo Blanc.

- At the conclusion of the novel Auto da Fe by Nobel Prize-winner Elias Canetti, the bibliophile protagonist immolates himself on a pile of his own library.

- The Japanese novel Toshokan Sensou is about the conflict between two military organizations after the Japanese government passed a law that allows the censorship of any media deemed to be potentially harmful to Japanese society, including book burning.

- The short story "Earth's Holocaust" from Nathaniel Hawthorne's Mosses from an Old Manse is about a society that burns everything that it finds offensive, including its literature. Special attention is paid to The Bible as the last book burned:

- "Upon the blazing heap of falsehood and worn-out truth--things that the earth had never needed, or had ceased to need, or had grown childishly weary of--fell the ponderous church Bible, the great old volume that had lain so long on the cushion of the pulpit, and whence the pastor's solemn voice had given holy utterance on so many a Sabbath day."

- In Part II of the play Tamburlaine, by Christopher Marlowe, Tamburlaine (the protagonist) burns a copy of the Qur'an after having conquered Asia Minor and Egypt. His book-burning and declaration of independence from any deity leads to his fatal illness, and subsequently the end of the play.

- In Anne of Green Gables, Anne watches in horror as her caretaker burns her book containing the poem "Lady of Shallot" as punishment for reading instead of doing her chores.

- Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 is a dystopian novel where books are outlawed and it is the job of a "fireman" to burn them. In the introduction of the 1967 Simon & Schuster book club edition, Bradbury implies that the Nazi book burnings drove him to write the short story "The Fireman" which was the precursor along with the foundation for his novel Fahrenheit 451, stating, "It follows then that when Hitler burned a book I felt it as keenly, please forgive me, as his killing a human, for in the long sum of history they are one and the same flesh."

- At the conclusion of Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose, the unique Medieval library which is at the center of the book's plot is burned and totally destroyed.

- A central event in the fantasy novel Titus Groan is the burning of the library of Earl Sepulchrave, which was the earl's sole pleasure in life - leading to his madness and eventual death.

- Iain Pears's book The Dream of Scipio is set in Provence, with the lives of three people at various historical periods interweaving with each other. Each of these lives includes an incident of book burning with a crucial importance. Manlius Hippomanes, a gallic aristocrat living in the time of the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, makes cynical use of Christianity for personal power and instills religious intolerance and antisemitism in his followers - and after his death, these followers set up a bonfire and burn Hippomanes' entire library of Classical works, believing themselves to be honoring his precepts. Olivier de Noyen, a poet and scholar active in the 14th Century Papal Court at Avignon, had to watch his father burning his beloved copy of Cicero - but then de Noyen re-wrote it from memory, and the incident determined him to devote his life to finding and preserving the books of antiquity. Julien Barneuve, an intellectual active during World War II, realizes the disastrous results of his collaboration with the pro-Nazi Vichy government and burns himself to death in a hut - starting the fire by burning his own manuscript of a work praising Hippomanes and condemning de Noyen.

- In the future depicted in Brian Stableford's The Halcyon Drift, one of the leading planets in the Galaxy is "New Alexandria", whose inhabitants are dedicated to the preservation and extension of knowledge, and are brought up to regard the destruction of books as the most heinous of deeds. Nevertheless, a protagonist agrees to help the Khor-Monsa, an alien species, in destroying books and records of their remote ancestors which were found in a drifting spaceship—since the books contained a shameful secret whose publication might have led to the present Khor-Monsa losing their social status and becoming targets of discrimination.

- In Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, the euphemistically-called "memory hole" is used to burn any book or written text which is inconvenient to the regime, and there is mention of the total destruction of all books published before 1960.

- In Journey to the Center of the Earth, the protagonist Axel suggests to his uncle, Professor Lindenbrock, that they should do more research on Arne Saknussemm and his works before attempting to duplicate Saknussemm's adventure into the center of the earth. Professor Lindenbrock tells Axel this is, regretfully, out of the question due to the fact that Saknussemm was out of favor with the leaders of his native country, who ordered all his books burned after his death.

- In The Book Thief, the protagonist, Liesel, attends a Nazi book burning ceremony. While there, she finds a book that has survived the fire and smuggles it home.

- In the detective novels of Pepe Carvalho by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, this charismatic private investigator based in Barcelona entertains himself every evening by burning one of the books of his huge personal library. It is not an act of censorship or cultural repression, but an individual, poetic mechanism to come to terms with personal disenchantment with life and culture.

In theatre

In his 1821 play, Almansor, the German writer Heinrich Heine — referring to the burning of the Muslim holy book, the Qur'an, during the Spanish Inquisition — wrote, "Where they burn books, so too will they in the end burn human beings." ("Dort, wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen.") Over a century later, Heine's own books were among the thousands of volumes that were torched by the Nazis in Berlin's Opernplatz.[37]

Film and television

- BBC Storyville's The Love of Books: A Sarajevo Story is a documentary film about how a group of passionate intellectuals, professionals and book lovers risked their lives to save the Gazi Husrav-Beg Library from destruction during the siege of Sarajevo. This is a film about the importance of books, and how libraries are at the heart of cultural identity, being repositories for history and memory.

- In one episode of The Simpsons, Lisa Simpson sees a bookmobile being driven by Reverend Lovejoy; however, the letters behind a tree reveal that it actually reads Book-Burning-Mobile.

- In the 1984 film Footloose, Reverend Moore sees townspeople burning books thinking they are dangerous to the children. He immediately orders it to stop, realizing the no dancing and music law in the town had gotten out of hand.

- In one episode of Fullmetal Alchemist, in order to prevent Edward from getting information on the Philosopher's Stone, the homunculi burn down one section of the library.

- In the Myst series of computer games and books, the only way to destroy the link to an Age is to destroy its Descriptive Book, usually by burning it.

- In the film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Indiana Jones journeys to Berlin in order to retrieve his father's journal, which gives information about finding the Holy Grail. He retrieves it during a Nazi book burning rally (although it was not targeted for burning itself), where it is inadvertently signed by Hitler himself.

- In the film The Name of the Rose, the library which houses rare books is burned.

- In the Red Dwarf episode "Marooned", Lister burns Rimmer's collection of books to heat Starbug. Rimmer initially protests, saying: "A book is a thing of beauty. The voice of freedom, the essence of civilisation." Lister counters: "Biggles Learns To Fly?"

- In the film Pleasantville, the people who are still black-and-white burn all the books in the library to keep people from becoming colored.

- The Crusade episode "The Needs of Earth" depicts a world that has burned its entire cultural heritage — all art, music, and literature — and hunts the person who has the last remaining copies.

- The 2002 film Equilibrium depicts a dystopian society which has eliminated human emotion, and burned all cultural influences that can cause emotion.

- In the 2004 disaster film The Day After Tomorrow, New York City is engulfed by a new Ice Age and characters seek shelter in the New York Public Library. To avoid freezing to death, the main character suggests burning books, much to the horror of two librarians.

- In the Family Guy episode "Not All Dogs Go to Heaven", Meg takes Brian to the church to burn books on science and evolution, citing them as "harmful to God". Among the burnt books are On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin, A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking, and a fictional book entitled Logic for First Graders.

- In a key scene of the film Der alte und der junge König (The Old and the Young King), a German Historical film made under Nazi rule in 1935, King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia is shown throwing into an open fire the beloved French-language books of his son, Crown Prince Friedrich (the future Friedrich II), as well as the Prince's flute. The film - banned after the fall of the Nazis as a piece of propaganda making manipulative use of history - presents this book burning as a positive and necessary act, which was needed in order to "educate" and "toughen up" the young prince, so as to "prepare him for becoming a great ruler".

- In the 2010 post-apocalyptic action film The Book of Eli, the main character Eli recounts to a young girl that, following a nuclear war, copies of religious texts (especially the Bible) were burnt by the survivors, who blamed religion as one of the causes of the war.

- The Book Thief

See also

References

- ↑ "Holocaust Encyclopedia: Book Burning".

- ↑ Edict by Emperor Constantine against the Arians. Athanasius (23 January 2010). "Edict by Emperor Constantine against the Arians". Fourth Century Christianity. Wisconsin Lutheran College. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ↑ Elaine Pagels, Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas (Random House, 2003), n.p.

- ↑ "NPNF2-04. Athanasius: Select Works and Letters". Ccel.org. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ↑ Knuth, R. (2006). Burning books and leveling libraries, p. 13. Praeger, London. ISBN 0275990079.

- ↑

- ↑ Duncan McMillan, Wolfgang van Emden, Philip E. Bennett, Alexander Kerr, Société Rencesvals, Guillaume d'Orange and the chanson de geste: essays presented to Duncan McMillan in celebration of his seventieth birthday by his friends and colleagues of the Société Rencesvals, University of Reading, 1984.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 1776–89.

- ↑ Rodkinson, Michael Levi (1918). The history of the Talmud, from the time of its formation, about 200 B. C. Talmud Society. pp. 66–75.

- ↑ Maccoby, Hyam (1982). Judaism on Trial: Jewish-Christian Disputations in the Middle Ages. Associated University Presses.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. Chicago, IL: Skyhorse Publishin. p. 158. ISBN 9781616084530.

- ↑ Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957)

- ↑ The Jewish Virtual Library - article The American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise [Retrieved 2015-12-19]

- ↑ Catholic encyclopedia, "Spanish Armada".

- ↑ "עכותור - מדריכי טיולים לעיר עכו ולכל הארץ | מדריך טיולים | מסלולי טיול לקבוצות עברית + צרפתית". Acco-tour.50webs.com. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ↑ O'Donnell, Jim (2003-11-20). "Patron saints". [email protected] (Mailing list). Georgetown University. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books:A Living History. Los Angeles: J.Paul Getty Museum. pp. 200–201. ISBN 9781606060834.

- ↑ Quoted in Publisher's Note to The Castle, Schocken Books.

- ↑ Habegger, Alfred (2001). My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson. p. 604.

- ↑ Farr (ed.), Judith (1996). Emily Dickinson: A Collection of Critical Essays. Prentice Hall International Paperback Editions. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-13-033524-1.

- ↑ Aziza Jafarzade, "Memoirs of 1937: Burning Our Books, The Arabic Script Goes Up in Flames," in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 14:1 (Spring 2006), pp. 24-25.

- ↑ Asaf Rustamov, "The Day They Burned Our Books," in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 7:3 (Autumn 1999), pp. 74-75.

- ↑ Reich, Wilhelm (1897-1957), International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis

- ↑ http://danmarkshistorien.dk/leksikon-og-kilder/vis/materiale/fantomet-paa-baalet-1955/

- ↑ Thomas, Lawrence. "Biblioclasm in Norway". Library and Archival Security 6. (1984): 13-16.

- ↑ Battles, Matthew. Library: An Unquiet History. Waterville, Maine: Thorndike Press, 2003.

- ↑ Knuth, Rebecca. Burning Books and Leveling Libraries. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2006.

- ↑ Ruggiero, Lucia. (n.d.). Digital books; could they make censorship and "book burning" easier? Digital Meets Culture. Retrieved October 22, 2015, from http://www.digitalmeetsculture.net/article/digital-books-could-they-make-censorship-and-book-burning-easier/

- ↑ Noted in Touring Club Italiano, Roma e Dintorni 1965:344.

- ↑ http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/the-books-have-been-burning-1.887172

- ↑ Leser, David (August 25, 2012). "The Da Vinci Mode". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ↑ Knuth, Rebecca. Burning Books and Leveling Libraries: Extremist Violence and Cultural Destruction. Praeger Publishers, 2006, p. 84.

- ↑ "Presss Release BC Sikh Community" (PDF). Harjas.com.

- ↑ "4 copies damaged in New Orleans by the flood caused by Hurricane Katrina". Sikhnn.com.

- ↑ "on the Nicobar Islands after the 2004 tsunami (end of page)". unitedsikhs.org.

- ↑ "Blog query about an accumulation of download printouts of Sikh sacred text". Mrsikhnet.com.

- ↑ Henley, Jon (10 September 2010). "Book-burning: fanning the flames of hatred". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

Further reading

Knuth, Rebecca (2006). Burning Books and Leveling Libraries: Extremist violence and Cultural Destruction. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

External links

- "On Book Burnings and Book Burners: Reflections on the Power (and Powerlessness) of Ideas" by Hans J. Hillerbrand

- "Burning books" by Haig A. Bosmajian

- "Bannings and burnings in history" - Book and Periodical Council (Canada)

- "The books have been burning: timeline" by Daniel Schwartz, CBC News. Updated 10 September 2010