Buddhism in Southeast Asia

Buddhism in Southeast Asia includes a variety of traditions of Buddhism including two main traditions: Mahāyāna Buddhism and Theravāda Buddhism. Historically, Mahāyāna Buddhism had a prominent position in this region, but in modern times most countries follow the Theravāda tradition.

Southeast Asian countries with a Theravāda Buddhist majority are Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.[1]

Vietnam continues to have a Mahāyāna majority due to Chinese influence.[2] Indonesia was Mahāyāna Buddhist since the time of the Sailendra and Srivijaya empires,[3] but now Mahāyāna Buddhism in Indonesia is now largely practiced by the Chinese diaspora, as in Singapore and Malaysia. Mahāyāna Buddhism is the predominant religion of most Chinese communities in Singapore. In Malaysia, Brunei, Philippines and Indonesia, it remains a strong minority.

History

Early traditions and Origins

Buddhism reached Southeast Asia both directly over sea from India and indirectly from Central Asia and China in a process that spanned most of the first millennium CE.[4]

In the third century B.C., there was disagreement among Ceylonese monks about the differences in practices between some councils of Bhikkhu monks and Vajjian Monks. The Bhikkhu monks affirmed Theravada traditions and rejected some of the practices of the Vajjian monks. It is thought that this sparked the split between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism.<[5]

Theravada Buddhism was formed and developed by Ceylon Bhikkhus during a period spanning from the third century B.C. to fifth century A.D.. Ceylonese influence, however, did not reach Southeast Asia until the eleventh century A.D..[5] Theravada Buddhism developed in Southern India and then traveled through Sri Lanka, Burma, and into Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Beyond.[4]

In the twelfth Mahayana Buddhism developed in Northern India and traveled through Tibet, China and into Vietnam, Indonesia and beyond.[4]

Buddhism is thought to have entered Southeast Asia from trade with India, China and Sri Lanka during the 1st, 2nd and 3rd centuries. One of the earliest accounts of Buddhism in Southeast Asia was of a Theravada Buddhist mission sent by the Indian emperor Ashoka to modern-day Burma in 250 BCE. The mission was received by the Mon kingdom and many people were converted to Buddhism. Via this early encounter with Buddhism, as well as others due to the continuous regional trade between Southeast Asia, China and South Asia, Buddhism spread throughout Southeast Asia. After the initial arrival in modern-day Burma, Buddhism spread throughout mainland Southeast Asia and into the islands of modern-day Malaysia and Indonesia. There are two primary forms of Buddhism found in Southeast Asia, Theravada and Mahayana. Theravada Buddhism spread from India to Sri Lanka then into the region as outlined above, and primarily took hold in the modern states of Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and southern Vietnam. Mahayana Buddhism is thought to have spread from both China and India during the first and second century into Southeast Asia. Mahayana took root primarily in maritime Southeast Asia, although there was also a strong influence in Vietnam, in part due to their connection with China.

The Khmer Empire and Srivijaya

During the 5th to 13th centuries, The Southeast Asian empires were influenced directly from India, so that these empires essentially followed the Mahāyāna tradition. The Srivijaya Empire to the south and the Khmer Empire to the north competed for influence, and their art expressed the rich Mahāyāna pantheon of bodhisattvas.

Srivijaya, a maritime empire centred at Palembang on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia, adopted Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism under a line of rulers named the Sailendras. Yijing described Palembang as a great centre of Buddhist learning where the emperor supported over a thousand monks at his court. Yijing also testified to the importance of Buddhism as early as the year 671 and advised future Chinese pilgrims to spend a year or two in Palembang.[6] Srivijaya declined due to conflicts with the Chola rulers of India, before being destabilised by the Islamic expansion from the 13th century.

From the 9th to the 13th centuries, the Mahāyāna Buddhist and Hindu Khmer Empire dominated much of the Southeast Asian peninsula. Under the Khmer, more than 900 temples were built in Cambodia and in neighbouring Thailand. Angkor was at the centre of this development, with a temple complex and urban organisation able to support around one million urban dwellers.

Early Spread of Theravada Buddhism

There are many factors that contributed to the early spread of Theravada Buddhism throughout Southeast Asia. The main three ways in which the religion was transported into the region is through systems of trade, marriage, and missionary work.[7] Buddhism has always been a missionary religion and Theravada Buddhism was able to spread due to the work and travel of missionaries. The Mon people are an ethnic group from Burma (Myanmar) that contributed to the success of Theravada Buddhism within Indochina.[8] Buddhism was likely introduced to the Mon people during the rule of Ashoka Maurya, the leader of the Mauryan Dynasty (268-232 BCE) in India.[9] Ashoka ruled his kingdom in accordance with Buddhist law and throughout his reign he dispatched court ambassadors and missionaries to bring the teachings of the Buddha to the east and Macedonia, as well to parts of Southeast Asia. India had trading routes that ran through Cambodia, allowing for the spread of these ideologies to easily occur.[9] The Mons are one of the earliest ethnic groups from Southeast Asia and as the region shifted and grew, new inhabitants to Burma adopted the Mon people’s culture, script, and religion.

The middle of the 11th century saw a decline of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. From the 11th to 13th century the Khmer Empire dominated the Southeast Asian peninsula.[8] Hindu was the primary religion of the Khmer Empire, with a smaller portion of people also adhering to Mahayana Buddhism. During the Khmer Rule, Theravada Buddhism was only found in parts of Malaysia, northwest Thailand, and lower Burma. Theravada Buddhism experienced a revival under the rule of Anawrahta Minsaw (1014-1077 AD).[10] Anawrahta was the ruler of the Pagan Empire in Burma and is considered to be the founder of the modern Burmese nation. Anawrahta embraced and revived the Mon people’s form of Theravada Buddhism through his building of schools and monasteries that taught and supported Theravada ideologies.[9] The success of Theravada Buddhism in Burma under the rule of Anawrahta allowed for the later growth of Buddhism in neighboring Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. The influences of the Mon people as well as the Pagan Empire are still felt today throughout the region. Currently, the Southeast Asian countries with the highest amounts of practicing Theravada Buddhists are Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia.

Political Power and Resistance

Buddhism has long been characterized by some scholars as an other-worldly religion, that is not rooted in economic and political activity. That is in part due to the influence of German sociologist, Max Weber, who was a prominent scholar of religion that has had a significant impact on the way Southeast Asian Buddhism is studied. Many contemporary scholars of Buddhism in Southeast Buddhism are starting to move away from the Weberian school of thought and identifying the role Buddhism has played in economic, political and every-day life in the region. Buddhism has also played a role in the consolidation of power and political resistance to throughout history, dating back to as early as the 10th and 11th century. Buddhist resistance has been a part of many significant historical moments, from the resistance to colonization and colonial powers, the creation of nation-states and the consolidation of political power within kingdoms and states.

Some of the earliest accounts of religious conflict that trace back to the 11th century took place in modern-day Burma. There was tension between Buddhist kings looking to create a more uniform religion and different sects of Buddhist worship. In particular, there was resistance from the cult of Nat worship, a religious practice that predates Buddhism in Burma. Buddhist kings of the time attempted to unify the different sects of Buddhism by the elimination of heretical movements. This was done so in order to maintain their power over their people and in an effort to purify the faith.

During the Nguyen dynasty of Vietnam in the 19th and 20th century, there was a strain between Confucian rulers and practitioners of Buddhism monks during the early unification of the empire. The rulers had a fear of potential rebellions emerging from monastic sites in the countryside and heavily criticized the spiritual practices of Buddhist sects, including a belief in invulnerability based on merit. After an attempt to de-legitimize Buddhist faith in the eyes of Vietnamese people through this criticism of their practices, they declared a war on Buddhism to squash any resistance to the consolidation of their empire

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, there were Buddhist resistance movements in the kingdom of Siam. These resistance movements were led by holy men or phu mi bun who had great power due to a high accumulation of merit. Some of these men claimed to have powers of invulnerability to enemy bullets and shared their powers through bathing others in holy water. An early phu mi bun rebellion was led by a former Buddhist monk, Phaya Phap, who resisted increased taxes in the province of Chiang Mai and proclaimed he would be the new, ideal Buddhist king of the region. These movements were not associated with mainstream Buddhism of the time, but many of the leaders had been ordained monks and utilized some Buddhist symbolism and philosophies.

Buddhist resistance also played a role in anti-colonialism movements. During the British colonization of Burma in the 19th century, there was intense Buddhist militarization and resistance against the colonial occupiers in an effort to restore the ideal Buddhist monarchy. There have also been more recent Buddhist resistance movements in Southeast Asia. After the communist takeover of Laos in 1975, some Buddhist monks feared that Buddhism was threatened by the Pathet Lao government. Many monks fled from Laos to Thailand and helped fund resistance movements from across the border. Monks who stayed in Laos supported resistance fighters with food and medical supplies. Another act of Buddhist resistance took place in Saigon in 1963 when a Mahayana Buddhist monk, Thic Quang Duc, self-emulated in the middle of a busy intersection. This self-emulation was an act of protest of the South Vietnamese Diem’s pro-catholic regime that persecuted Buddhists.

Theravada Traditions

Theravada Buddhism in SE Asia is rooted in Ceylonese Buddhism that traveled from Sri Lanka to Malaysia (then Burma) and later to lower Thailand.[11]

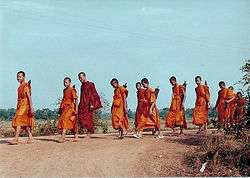

The Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha are the three fundamental aspects of Theravada Buddhist thought. The Buddha is a teacher of gods and men. Unique to Theravada Buddhism is the view that the Buddha is not a god to be worshiped, but rather a teacher to be followed. The Dhamma consists of the teachings of the Buddha. It is path made through the words and deeds of the Buddha that is to be followed. The path leads the follower from the Realm of Desire, to the Realm of Form, the Formless Realm with the ultimate destination being Nirvana. The Sangha (gathering) refers to the two types of followers of the Buddha: lay and monastic. The monastic followers adhere to the Bhikkhu-way. The Bhikku lead a very disciplined life modeled after the Buddha, going from pabbajja or novice ordination (samanera) to upasampada or higher ordination (Bhikkhu).[11]

Mahāyāna Traditions

Mahāyāna Buddhism in SE Asia is rooted in Buddhist traditions that traveled from Northern India through Tibet and China and eventually made their way to Vietnam, Indonesia and other parts of southeast Asia.[4]

Mahāyāna Buddhism consists of a large variety of different sūtras. A defining feature of Mahāyāna Buddhism is its' inclusiveness of a wide range of doctrines. The Mahāyāna tradition includes the doctrine of the three bodies of the Buddha (trikāya). The first is the body of transformation (nirmānakāya), the second is the body of bliss/enjoyment (sambhogakāya), and the third is the body of law/essence (dharmakāya). Each body makes sense of a different function of the Buddha.[12] Another common theme in the Mahāyāna tradition of Buddhism, is the path of the bodhisattva. Stories are told about prior lives of the Buddha as a bodhisttva. These stories teach the qualities that are desirable to a good Mahāyāna Buddhist. Bodhisttvas are self-less as they care not only for their own salvation, liberation, and happiness, but also for the salvation, liberation, and happiness of others. A bodhisttva will make it almost all of the way to Nirvana, but go back in order to help others go farther. The bodhisttva is contrasted with the pratyekabuddha who is only self-enlightened and not fully enlightened like the bodhisttva. The pratyekabuddha is seen as selfish as they only seek their own enlightenment and do not try to help others.[12]

Buddhism by Country

Currently, there are approximately 190-205 million Buddhists in Southeast Asia, making it the second largest religion in the region, after Islam. Approximately 35 to 38% of the global Buddhist population resides in Southeast Asia. The following is a list of Southeast Asian countries from most to least adherents of Buddhism as a percent of the population.

- Thailand has the largest number of Buddhists with approximately 95% of its population of 67 million adhering to Buddhism, placing it at around 63.75 million.[13][14]

- Myanmar has around 59 million Buddhists, with 89% of its 66 million citizens practicing Theravada Buddhism.[15][16] Around 1% of the population, mainly the Chinese, practice Mahayana Buddhism alongside Taoism, but are strongly influenced by Theravada Buddhism.

- Vietnam may have a large number of Buddhists, but the Communist government under-reports the religious adherence of its citizens. It has around 44 million Buddhists, around half its population.[17][18] The majority of Vietnamese people practice Mahayana Buddhism due to the large amount of Chinese influence.[19]

- 95% of Cambodia's population adheres to Theravada Buddhism, placing its Buddhist population at around 14 million.[20]

- Malaysia has about 20% of its citizens, mainly ethnic Chinese, with significant numbers of ethnic Thais, Khmers, Sinhalese and migrant workers, practising Buddhism. The Chinese mainly practice Mahayana Buddhism, but due to the efforts of Sinhalese monks, Theravada also enjoys a significant following.[21][22]

- Communist Laos has around 5 million Buddhists, who form roughly 70% of its population.[23][24]

- Indonesia has around 4.75 million Buddhists (2% of its population), mainly amongst its Chinese population. Most Indonesian Buddhists adhere to Theravada Buddhism, mainly of the Thai tradition.[25]

- Singapore have around 2 million Buddhists, forming around 33% of their populations respectively.[26] Singapore has the most vibrant Buddhist scene with all three major traditions having large followings. Mahayana Buddhism has the largest presence amongst the Chinese, while many immigrants from countries such as Myanmar, Thailand and Sri Lanka practice Theravada Buddhism.[27]

- Philippines have around the 2% of the total population or around 2 millions. All the important schools of Buddhism are well represented in Philippines although it is predominantly Mahayana School of Buddhism that is practiced in the country. Other Schools of Buddhism are also making their presence felt gradually amongst the people. Prime amongst these are - Nichiren Buddhism, Thervada Buddhism and Vajrayana Buddhism.

- Brunei, which has the smallest population in Southeast Asia, has around 13%[28] of its citizens and a significant migrant worker population adhering to Buddhism, at around 65,000.[29]

See also

- Buddhism in Asia

- Buddhism in East Asia

- Buddhism by country

- Jainism in Southeast Asia

- Hinduism in Southeast Asia

- Islam in Southeast Asia

References

- Ancient History Encyclopedia. 2014. “Buddhism.” Retrieved Oct 9th, 2016. ().

- Baird, Ian G. 2012. “Lao Buddhist Monks' Involvement in Political and Military Resistance to the Lao People's Democratic Republic Government since 1975” The Journal of Asian Studies. 71 (3): 655-677.

- Buswell, R. 2004. Encyclopedia of Buddhism. New York: Macmillan Reference, USA.

- Ileto, R. 1993. “Religion and Anti-Colonial Movements” The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 197–248.

- Reat, N. 1994. Buddhism : A History. Berkeley, CA: Asian Humanities Press.

- Tarling, N., & Cambridge University Press. 1992. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge, UK ; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press.

- Kitiarsa, Pattana. 2009. "Beyond the Weberian Trails. An Essay on the Anthropology of Southeast Asian Buddhism." Religion Compass3(2): 200-224.

- Keyes, Charles. 2014. Finding Their Voice: Northeastern Villagers and the Thai State. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books

- "The burning monk, 1963". rarehistoricalphotos.com. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- ↑ Kitiarsa, Pattana (2009-03-01). "Beyond the Weberian Trails: An Essay on the Anthropology of Southeast Asian Buddhism". Religion Compass. 3 (2): 200–224. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00135.x. ISSN 1749-8171.

- ↑ CPAmedia: Buddhist Temples of Vietnam Archived 8 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Singapore Philatelic Museum website: Southward Expansion of Mahayana Buddhism - Southeast Asia Archived 19 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 Tai Thu, Nguyen (2008). The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. Washington DC: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. pp. 2–9. ISBN 1-56518-098-4.

- 1 2 Lester, Robert, C (1973). Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia. United States: Ann Arbor Paperbacks. pp. 1–162. ISBN 0-472-06184-4.

- ↑ Jerry Bently, 'Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 72.

- ↑ Kitiarsa, Pattana (2009). Beyond the Weberian Trails: An Essay on the Anthropology of Southeast Asian Buddhism. Religion Compass. p. 205.

- 1 2 Guillon, Emmanuel (1999). The Mons: A Civilization of Southeast Asia. Bangkok: Siam Society under Royal Patronage. p. 113.

- 1 2 3 Keown, Damien (2013). Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 80.

- ↑ Maraldo, John (1976). Buddhism in the Modern World. New York: Macmillan.

- 1 2 Lester, Robert C. (1973). Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia. USA: Ann Arbor Paperback. pp. 1–130. ISBN 0-472-06184-4.

- 1 2 Olson, Carl (2005). The Different Paths of Buddhism. Rutgers University Press. pp. 149–181. ISBN 0-8135-3561-1.

- ↑ "The CIA World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ state.gov - Thailand

- ↑ "Crisis in Myanmar Over Buddhist-Muslim Clash". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "The World Factbook: Burma". CIA. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "state.gov – Vietnam 2012 (included over 50% Mahayana + 1.2% Theravada + 3% Hoa Hao Buddhism and other new Vietnamese sects of Buddhism)". state.gov. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2006/71363.htm

- ↑ Vietnam Tourism - Over 70 percent of the population of Vietnam are either Buddhist or strongly influenced by Buddhist practices. Archived 9 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine., mtholyoke.edu Buddhist Crisis 1963 - in a population that is 70 to 80 percent Buddhist

- ↑ "The World Factbook: Cambodia". CIA. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Religious Adherents, 2010 - Malaysia". World Christian Database. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ state.gov (19.8% Buddhist + 1.3% Taoism/Confucianism/Chinese Folk Religion

- ↑ "CIA – The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ "Religious Adherents, 2010 – Laos". World Christian Database. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Religious Adherents, 2010 – Indonesia (0.8% Buddhist + 0.9% Chinese Folk Religion/Confucianism)". World Christian Database. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ Singapore Department of Statistics (12 January 2011). "Census of population 2010: Statistical Release 1 on Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ↑ "www.state.gov". state.gov. 15 September 2006. Retrieved 20 November 2011., "CIA Factbook – Singapore". Cia.gov. Retrieved 20 November 2011., "Religious Adherents, 2010 – Singapore (14.8% Buddhist + 39.1% Chinese Folk Religion = 53.9% in total)". World Christian Database. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "The World Factbook: Brunei". CIA. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Religious Adherents, 2010 – Brunei (9.7% Buddhist + 5.2% Chinese Folk Religion + 1.9% Confucianist)". World Christian Database. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

.jpg)