Camelid

| Camelids Temporal range: 45–0 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Bactrian camel walking in the snow | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Superfamily: | Cameloidea |

| Family: | Camelidae Gray, 1821 |

| Genera | |

| |

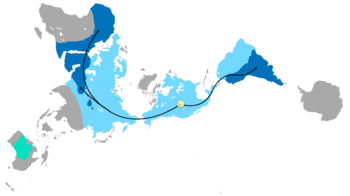

| Current range of camelids, all species | |

Camelids are members of the biological family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The extant members of this group are: dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bactrian camels, llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos.

Camelids are even-toed ungulates classified in the order Cetartiodactyla, along with pigs, hippopotamuses, whales, deer, giraffes, cattle, goats, antelope, and many others.

Characteristics

Camelids are large, strictly herbivorous animals with slender necks and long legs. They differ from ruminants in a number of ways.[2] Their dentition show traces of vestigial central incisors in the upper jaw, and the third incisors have developed into canine-like tusks. Camelids also have true canine teeth and tusk-like premolars, which are separated from the molars by a gap. The musculature of the hind limbs differs from those of other ungulates in that the legs are attached to the body only at the top of the thigh, rather than attached by skin and muscle from the knee upwards. Because of this, camelids have to lie down by resting on their knees with their legs tucked underneath their bodies.[1] They have three-chambered stomachs, rather than four-chambered ones; their upper lips are split in two, with each part separately mobile; and, uniquely among mammals, their red blood cells are elliptical.[2] They also have a unique type of antibodies which lack the light chain, in addition to the normal antibodies found in other mammals. These so-called heavy-chain antibodies are being used to develop single-domain antibodies with potential pharmaceutical applications.

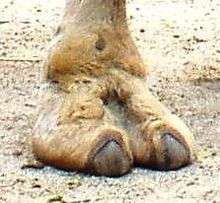

Camelids do not have hooves, rather they have two-toed feet with toenails and soft foot pads (Tylopoda is Greek for "padded foot"). Most of the weight of the animal rests on these tough, leathery sole pads. The South American camelids, adapted to steep and rocky terrain, can move the pads on their toes to maintain grip.[3] Many fossil camelids were unguligrade and probably hooved, in contrast to all living species.[4]

Camelids are behaviorally similar in many ways, including their walking gait, in which both legs on the same side are moved simultaneously. The consequent swaying motion of camelids large enough for human beings to ride is legendary.

Dromedary camels, bactrian camels, llamas and alpacas are all induced ovulators.[5]

The three Afro-Asian camel species have developed extensive adaptations to their lives in harsh, near-waterless environments. Wild populations of the Bactrian camel are even able to drink brackish water, and some herds live in nuclear test areas.[6]

Comparative table of the eight mammals in the family Camelidae (ordered by weight):

| Camel-like mammal | Image | Natural range | Weight | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camelus | |||||||||

| Bactrian camel | |

Central Asia (entirely domesticated) |

300 to 1,000 kg (660 to 2,200 lb) | ||||||

| Wild Bactrian camel |  |

Central Asia (entirely wild) |

300 to 820 kg (660 to 1,800 lb) | ||||||

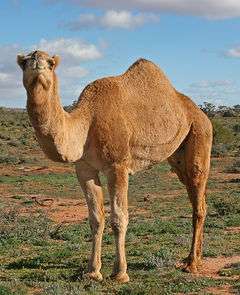

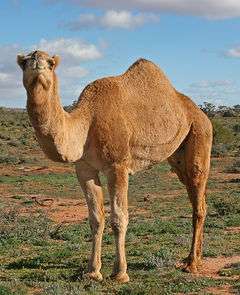

| Dromedary or Arabian camel |

|

South Asia and Middle East (entirely domesticated) |

300 to 600 kg (660 to 1,320 lb) | ||||||

| Lama | |||||||||

| Llama | .jpg) |

(domestic form of guanaco) | 130 to 200 kg (290 to 440 lb) | ||||||

| Guanaco |  |

South America | c. 90 kg (200 lb) | ||||||

| Vicugna | |||||||||

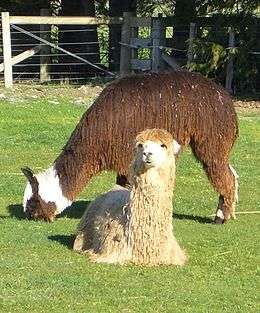

| Huacaya Alpaca |  |

(domestic form of vicuña) | 48 to 84 kg (106 to 185 lb) | ||||||

| Suri Alpaca |  |

(domestic form of vicuña) | 48 to 84 kg (106 to 185 lb) | ||||||

| Vicuña |  |

South American Andes | 35 to 65 kg (77 to 143 lb) | ||||||

Evolution

Camelids are unusual in that their modern distribution is almost the inverse of their area of origin. Camelids first appeared very early in the evolution of the even-toed ungulates, around 45 million years ago during the middle Eocene, in present-day North America. Among the earliest camelids was the rabbit-sized Protylopus, which still had four toes on each foot. By the late Eocene, around 35 million years ago, camelids such as Poebrotherium had lost the two lateral toes, and were about the size of a modern goat.[4][7]

The family diversified and prospered, but remained confined to the North American continent until only about two or three million years ago, when representatives arrived in Asia, and (as part of the Great American Interchange that followed the formation of the Isthmus of Panama) South America. A high arctic camel from this time period has been documented in the far northern reaches of Canada.

The original camelids of North America remained common until the quite recent geological past, but then disappeared, possibly as a result of hunting or habitat alterations by the earliest human settlers, and possibly as a result of changing environmental conditions after the last ice age, or a combination of these factors. Three species groups survived: the dromedary of northern Africa and southwest Asia; the Bactrian camel of central Asia; and the South American group, which has now diverged into a range of forms that are closely related, but usually classified as four species: llamas, alpacas, guanacos, and vicuñas.

Fossil camelids show a wider variety than their modern counterparts. One North American genus, Titanotylopus, stood 3.5 m at the shoulder, compared with the about 2 m of the largest modern camelids. Other extinct camelids included small, gazelle-like animals, such as Stenomylus. Finally, a number of very tall, giraffe-like camelids were adapted to feeding on leaves from high trees, including such genera as Aepycamelus, and Oxydactylus.[4]

It is still debated whether the wild Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus) is in fact a distinct species or a subspecies (Camelus bactrianus ferus).[8][9] The divergence date is 0.7 million years ago, long before the start of domestication.[9]

Scientific classification

Family Camelidae

- †Subfamily Poebrodontinae

- †Subfamily Poebrotheriinae

- †Subfamily Miolabinae

- †Subfamily Stenomylinae

- †Subfamily Floridatragulinae

- Subfamily Camelinae

- Tribe Lamini

- Tribe Camelini

- Genus: Camelus

- Dromedary, Camelus dromedarius

- Bactrian camel, Camelus bactrianus

- Wild Bactrian camel, Camelus ferus

- †Syrian camel, Camelus moreli

- †Camelus sivalensis

- Genus: Camelops

- Genus: Paracamelus

- †Paracamelus gigas

- Genus: Camelus

Phylogeny

| Camelid ancestor | North America

12-25 mya |

Lamini | 10.4 mya | 1.4 mya | Guanaco | South America | |

| Vicuña | |||||||

| Camelini | 8 mya | Bactrian camel | Asia | ||||

| Dromedary | Asia, Africa | ||||||

Extinct genera

| Genus name | Epoch | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Aepycamelus | Miocene | Tall, s-shaped neck, true padded camel feet |

| Camelops | Pliocene-Pleistocene | Large, with true camel feet, hump status uncertain |

| Floridatragulus | Early Miocene | A bizarre species of camel with a long snout |

| Eulamaops | Pleistocene | From South America |

| Hemiauchenia | Miocene-Pleistocene | A North and South American lamine genus |

| Megacamelus | Miocene-Pleistocene | The largest species of camelid |

| Megatylopus | Miocene-Early Pleistocene | Large camelid from North America |

| Oxydactylus | Early Miocene | The earliest member of the "giraffe camel" family |

| Palaeolama | Pleistocene | A North and South American lamine genus |

| Poebrotherium | Oligocene | This species of camel took the place of deer and antelope in the White River Badlands. |

| Procamelus | Miocene | Ancestor of extinct Titanolypus and modern Camelus |

| Protylopus | Late Eocene | Earliest member of the camelids |

| Stenomylus | Early Miocene | Small, gazelle-like camel that lived in large herds on the Great Plains |

| Titanotylopus | Miocene-Pleistocene | Tall, humped, true camel feet |

The newly discovered giant Syrian camel has yet to be officially described.

References

- 1 2 Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1987). A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. p. 208. ISBN 0-521-34697-5.

- 1 2 Fowler, M.E. (2010). "Medicine and Surgery of Camelids", Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. Chapter 1 General Biology and Evolution addresses the fact that camelids (including camels and llamas) are not ruminants, pseudo-ruminants, or modified ruminants.

- ↑ Franklin, William (1984). Macdonald, D., ed. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 512–515. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- 1 2 3 Savage, RJG; Long, MR (1986). Mammal Evolution: an illustrated guide. New York: Facts on File. pp. 216–221. ISBN 0-8160-1194-X.

- ↑ Chen, B.X., Yuen, Z.X. and Pan, G.W. (1985). "Semen-induced ovulation in the bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus)." (PDF). J. Reprod. Fert. 74 (2): 335–339. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ Wild Bactrian Camels Critically Endangered, Group Says National Geographic, 3 December 2002

- ↑ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. pp. 274–277. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ↑ Cui, Peng; Ji, Rimutu; Ding, Feng; Qi, Dan; Gao, Hongwei; Meng, He; Yu, Jun; Hu, Songnian; Zhang, Heping (2007-07-18). "A complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the wild two-humped camel (Camelus bactrianus ferus): an evolutionary history of camelidae". BMC Genomics. 8 (1). doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-241. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 1939714

. PMID 17640355.

. PMID 17640355. - 1 2 Ji, R.; Cui, P.; Ding, F.; Geng, J.; Gao, H.; Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; Hu, S.; Meng, H. (2009-08-01). "Monophyletic origin of domestic bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) and its evolutionary relationship with the extant wild camel (Camelus bactrianus ferus)". Animal Genetics. 40 (4): 377–382. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2008.01848.x. ISSN 1365-2052. PMC 2721964

. PMID 19292708.

. PMID 19292708.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Camelidae. |