Castile and León

| Castilla y León Castilla y León (Spanish) Castiella y Llión (Leonese) Castela e León (Galician) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous community | |||

| Castile and León (Spanish) | |||

| |||

.svg.png) Location of Castile and Leon within Spain | |||

| Coordinates: 41°23′N 4°27′W / 41.383°N 4.450°WCoordinates: 41°23′N 4°27′W / 41.383°N 4.450°W | |||

| Country | Spain | ||

| Capital | Valladolid (de facto[1]) | ||

| Government | |||

| • President | Juan Vicente Herrera (PP) | ||

| Area(18.6% of Spain; Ranked 1st) | |||

| • Total | 94,222 km2 (36,379 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2011) | |||

| • Total | 2,558,463 | ||

| • Density | 27/km2 (70/sq mi) | ||

| • Pop. rank | 6th | ||

| • Percent | 5.42% of Spain | ||

| Demonym | |||

| ISO 3166-2 | CL | ||

| Official languages | Spanish (Leonese and Galician have special status) | ||

| Statute of Autonomy | 2 March, 1983 | ||

| Parliament | Cortes Generales | ||

| Congress seats | 31 (of 350) | ||

| Senate seats | 39 (of 266) | ||

| Website | Junta de Castilla y León | ||

Castile and León (English /kæˈstiːl ən leɪˈoʊn/; Spanish: Castilla y León [kasˈtiʎa i leˈon]; Leonese: Castiella y Llión [kasˈtjeʎa i ʎiˈoŋ]; Galician: Castela e León [kasˈtɛla e leˈoŋ]) is an autonomous community in north-western Spain. It was constituted in 1983, although it existed for the first time during the First Spanish Republic in the 19th century. León first appeared as a Kingdom in 910, whilst the Kingdom of Castile gained an independent identity in 1065 and was intermittently held in personal union with León before merging with it permanently in 1230. It is the largest autonomous community in Spain and the third largest region of the European Union, covering an area of 94,223 square kilometres (36,380 sq mi) with an official population of around 2.5 million (2011).

The organic law of Castile and León, under the Spanish Constitution of 1978, is the bi-region's Statute of Autonomy. The statute lays out the basic laws of the region and defines a series of essential values and symbols of the inhabitants of Castile and León, such as their linguistic patrimony (the Castilian language, which English speakers commonly refer to simply as Spanish, as well as Leonese and Galician), as well as their historic, artistic, and natural patrimony (see Castilian people). Other symbols alluded to are the coat of arms, flag, and banner; there is also allusion to a regional anthem, though as of 2013 none has been adopted.

It is the region of the world with the most World Heritage Sites, 8 in total. 23 April is designated Castile and León Day, commemorating the defeat of the comuneros at the Battle of Villalar during the Revolt of the Comuneros, in 1521.

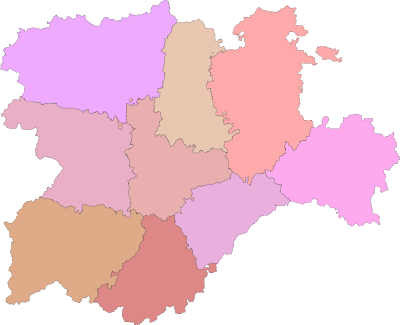

Political divisions

The community is formed from nine provinces: Avila, Burgos, Leon, Palencia, Salamanca, Segovia, Soria, Valladolid and Zamora. The provincial capitals fall in the homonymous cities to their provinces concerned.

|

Geography

Castile and León is bordered by Portugal and Galicia to the west and by Asturias and Cantabria to the north. Aragon, the Basque Country and La Rioja is to the east and the border to the south is with Madrid, and with Castile-La Mancha and Extremadura to the southwest.

Castile and León is in the Meseta Central, a plateau in the middle of the northern half of the Iberian Peninsula; the Spanish part of the Douro River basin is nearly coterminous. There is also El Bierzo (León) and Laciana (León), Valle de Mena (Burgos), and the Valle del Tietar (Ávila), very secluded mountain valleys including some from neighbouring valleys and stretches.

Terrain

Much of its territory consists of a large, central plateau - the Meseta. Its height lies between 700-1000m.[2]

Rivers

The most prominent hydrographic feature of Castile and León is the River Douro (Spanish: Duero) and its tributaries. The Douro runs 897 kilometres (557 mi) from its headwaters in the Picos de Urbión in Soria to its mouth at the Portuguese city of Porto. Flowing into the Douro from the north, on its right bank, are the Pisuerga, the Valderaduey and the Esla, its most capacious tributaries, and from the east, on its left bank, the lesser flows of the Adaja and Duratón. After passing the city of Zamora, the Douro flows through a canyon in the Arribes del Duero Natural Park where it constitutes the border with Portugal, flowing north. From its left bank, it receives the waters of such important tributaries as the Tormes, Huebra, Águeda, the Côa and the Paiva, all originating in the Sistema Central. From the right bank, it receives the waters of the Sabor, the Tua and the Támega, originating in the Galician Massif. Beyond the Arribes, the Douro turns west, flowing through Portugal to the Atlantic.

Climate

The highest rainfall is found in Leon, with a yearly average of 556mm, whilst Palencia has the lowest amount.[3] The region has a continental climate, characterized by relatively cold winters and dry warm summers. This is the result of distance from the sea and high altitude. Only two small areas have a milder climate, the section of the province of Avila which extends south of Gredos mountains into the Tiétar valley, and the area where the Duero river forms a natural border between Zamora province and Portugal known as the Arribes del Duero.

Regional administration and government

Castile and León is divided into nine provinces:

Each of these provinces is named after its respective provincial capital.

Autonomous Executive

The executive of Castile and León is known as the Junta de Castilla y León in Spanish.

It has one head of the Regional Executive, the President of the Junta of Castile and León, and twelve departments: Two Vicepresidencias and ten ministries (Spanish: Consejerías).

- Seat of the Regional Executive: neighbourhood of Covaresa, Valladolid

- Seat of the Accounting Committee: Palencia

Another party, the left-of-centre Castilian Nationalist Tierra Comunera - ACAL, has contested previous elections and has held seats in the Regional Courts in the past, but as of 2011 it is not represented in that body.

| Political party | Autonomic elections, 2011[4] | Autonomic elections, 2007[5] | Autonomic elections, 2003 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Seats | Percentage | Seats | Percentage | Seats | |

| Partido Popular de Castilla y León | 51.59% | 53 | 49.41% | 48 | 48.56% | 48 |

| Partido Socialista de Castilla y León | 29.61% | 29 | 37.49% | 33 | 36.74% | 32 |

| Unión del Pueblo Leonés | 1.85% | 1 | 2.74% | 2 | 3.88% | 3 |

| Izquierda Unida LVCyL | 4.89% | 1 | 3.09% | 0 | 3.43% | 0 |

| Tierra Comunera - ACAL | - | - | 1.16% | 0 | 1.19% | 0 |

Culture

Languages

Besides the dominant Castilian Spanish, three other regional languages figure in the linguistic patrimony of Castile and León. Two of these are recognized explicitly in the Statute of Autonomy. The Leonese language, according to the Statute, "will be the object of specific protection [...] for its particular value in the linguistic heritage of the Community".[6] The Galician language, according to the statute, "merits respect and protection in the places where it is habitually used,[7] which is effectively to say the portions of the comarcas of El Bierzo and Sanabria bordering Galicia. In addition, although unmentioned in the Statute, in the comarca of El Rebollar in the province of Salamanca, people speak a variety of Extremaduran[8] known as Habla del Rebollar ("the speech of Rebollar").

Education

- Universities

- Public

- Private

- Catholic University of Ávila (Universidad Católica Santa Teresa de Jesús de Ávila)

- Miguel de Cervantes European University (Valladolid)

- IE University (Instituto de Empresa Universidad, Segovia)

- Pontifical University of Salamanca

History

Castile and León traces its history to the medieval kingdoms of Castile and León, which were permanently united under the Crown of Castile in 1301. Together with other Christian-ruled Iberian kingdoms, the separate monarchies of Castile and León participated in the Reconquista, the re-conquest of Iberia from the Moors, its medieval Muslim rulers.

The first dynastic union of León and Castile came about in 1037, when Ferdinand, the 20-year-old Count of Castile, defeated his brother-in-law Bermudo III of León in battle and claimed the Crown of León through the rights of his own wife, Sancha, Bermudo's sister. Although he declared himself Emperor of All Spain in 1056, the union ended with Ferdinand's death in 1065, when Castile, León, and Galicia each passed to a different one of Ferdinand's sons and certain cities to his daughters, with a further division of spheres of influence in the Muslim taifas. The arrangement did not hold. The sons soon fought; eventually one son, Alfonso VI of León again created an effective union and in 1077 again claimed the title of Emperor of All Spain. However, his death in 1109 left the kingdoms again disunited.

The medieval Cortes of León is one of the earliest ancestors of Europe's parliaments. The remote origins of the Cortes dates back to the early 12th century. The Cortes of León of 1188 called by Alfonso IX is one of the earliest documented gatherings of the estates in which commoners of the cities and towns are represented beside the clergy and nobility as counselors to the monarch. Alfonso gathered similar assemblies in 1202 in Benavente and 1208 in León.

In the kingdom of Castile, the first curia—a large assembly to address the affairs of the kingdom—appears to have been convoked by Alfonso VIII in 1187 at San Esteban de Gormaz, with the leading men of fifty cities in attendance. In his capacity as king of Castile, Ferdinand III received the homage of large delegations at Valladolid in 1217 and convoked a curia in 1219 at Burgos.

Valladolid was home to a number of Castilian kings between the 12th and 17th centuries.[9]

Antecedents to the autonomous community

Spain has alternated between regionalism and centralization several times in the last century and a half. In 1869, the republicans of the present Castile and León plus the provinces of Santander (now Cantabria) and Logroño (now La Rioja) had drafted the Castilian Federal Pact (Pacto Federal Castellano), which projected the creation of a federated state under the name Castilla la Vieja (Old Castile) in these eleven provinces. During the First Republic (1873–1874), the Republican Democratic Federal Party (Partido Republicano Democrático Federal) intended to make this a reality.[10] However, the fall of the Republic at the beginning of 1874 put an end to this initiative.[11]

In 1921, on the fourth centenary of the Battle of Villalar, the municipal government of Santander, Cantabria advocated for the establishment of a Castilian commonwealth of these same eleven provinces. In late 1931 and early 1932, the priest Eugenio Merino, in León, wrote a piece for the Diario de León stating a basis for Castilian-Leonese regionalism.[12]

During the Second Republic, especially in 1936, there was a great deal of regionalist activity favorable to a region of eleven provinces, including the elaboration of the basis of a statute of autonomy. The Diario de León advocated for the formalization of this initiative and the constitution of an autonomous region as follows: "to unite in one personality León and Old Castile around the great basin of the Douro, without falling now into simple village rivalries."[13] The establishment of a centralising regime after the Spanish Civil War brought an end to these aspirations for regional autonomy.

After the death of the dictator Francisco Franco unleashed the Spanish transition to democracy, there was an upwelling of Castilian-Leonese regionalist, autonomist and nationalist organizations, such as Alianza Regional de Castilla y León (1975), Instituto Regional de Castilla y León (1976) and the Autonomic Nationalist Party of Castile and León (Partido Autonómico Nacionalista de Castilla y León, PANCAL, 1977). None of these survive today, but similar sentiments are now represented by Unidad Regionalista de Castilla y León (1993).[14]

Forming the autonomous community

Castile and León obtained a "pre-autonomic" regime by the Royal Decree Ley 20/1978, June 13, 1978. This set the region on the course toward establishing an autonomous community, a path that had been offered first to Catalonia toward the end of 1977 and would eventually be granted to every part of Spain. Five years later, in 1983, the autonomous community of Castile and León was made concrete by the Statute of Autonomy accepted by both the community and the Spanish state.

The Provincial Deputation of León agreed on April 16, 1980 to endorse the Castilian-Leonese process, but then revoked that support January 13, 1983, just as the proposed Organic Law was before the Spanish parliament. The Constitutional Court of Spain upheld the first of these two contradictory Leonese resolutions.[15] The court's decision was met by demonstrations in León and elsewhere in the Leonese territories in favor of a policy of León solo ("León alone"). The roughly 90,000 people who gathered in León at that time[16] constituted the largest demonstration in that city between the revival of democracy and the demonstrations after the 2004 Madrid train bombings.[17]

Demography

The most recent official census by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, as January 1, 2011, gave a population of 2,558,463 (1,267,671 males and 1,290,792 females) representing 5.42 percent of the population of Spain. As of January 2011 the population of Castile and León, by province, stood as follows: Ávila, 172,704 inhabitants; Burgos, 375,657; León, 497,799; Palencia,171,668; Salamanca, 352,986; Segovia, 164,169; Soria, 95,223; Valladolid, 534,874; and Zamora, 193,383.[18]

Depopulation in the mid-20th century

Even before the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), the rural areas (and smaller cities) of present-day Castile and León were losing population due to emigration to Spain's large cities and abroad. This trend accelerated in the decade immediately after the Civil War. The growth of a strong industrial centre in Valladolid, including Spain's first automobile factory—the Renault plant led by the soldier and engineer Manuel Jiménez Alfaro—mitigated, but did not stop, the emigration. In both the 1960s and 1980s, the urban nuclei and provincial capitals gained population, but the region as a whole still suffered a net loss. To this day, the region has an aging population and a low birth rate contrasted against a merely average death rate by national standards.

Present-day population distribution

In 1960 only 20.6 percent of the population of present-day Castile and León was urban; by 1991 that percentage had risen to 42.3 percent. The decline in rural population has apparently been somewhat stemmed, with a 1998 statistic showing 43 percent.

Many rural areas became very sparsely populated in the mid-to-late 20th century. In 1986 there were seven times as many municipalities with less than 100 inhabitants as in 1960.

A recent study from University of Porto (Portugal) highlighted Castile and León - particularly the province of Salamanca - as one of the European regions where old people could expect to live longer.[19]

Notable cities include the nine provincial capitals plus Miranda de Ebro and Aranda de Duero in the province of Burgos, Ponferrada and San Andrés del Rabanedo in León, Béjar in Salamanca, and Medina del Campo and Laguna de Duero in Valladolid.

Of the 2,247 municipalities in the autonomous community, the 2000 census shows 1,970 with 1,000 or fewer inhabitants; 234 between 1,001 and 5,000; 20 between 5,001 and 10,000; 10 between 10,001 and 20,000; 6 between 20,001 and 50,000; 3 between 50,001 and 100,000; and 4 with over 100,000 inhabitants. Those last are Valladolid (319,943 in 2007), Burgos (174,075), Salamanca (159,754) and León (135,059). At the other extreme Blasconuño de Matacabras (Ávila) has a population of 18, Reinoso (Burgos) has 24, Villarmentero de Campos (Palencia), has 14, and Gormaz (Soria), 17.

| City | Population | City | Population | City | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valladolid | 313,437 | Ponferrada | 68,508 | Miranda de Ebro | 38,930 | ||

| Burgos | 179,251 | Zamora | 65,525 | Aranda de Duero | 33,229 | ||

| Salamanca | 153,472 | Ávila | 59,008 | San Andrés del Rabanedo | 31,562 | ||

| León | 132,744 | Segovia | 55,220 | Laguna de Duero | 22,334 | ||

| Palencia | 81,552 | Soria | 39,987 | Medina del Campo | 21,607 |

Economy

Castilla y Leon accounts for 5.2% of Spain's GDP.[20]

Work force

In 2001 the work force was 1,005,200 with 884,200 employed, meaning 12.1 percent of the work force were out of work. 10.9 percent of the employed population work in agriculture, 20.6 percent in industry, 12.7 percent in construction, and 63.1 percent in the service sector.

In 2007, the unemployment rate was down to 6.99 percent,[21] but the late-2000s recession drove that number up to 14.14 percent by July 2009.[22]

Primary sector (agriculture and livestock)

Castile and León has roughly 5,783,831 hectares (14,292,160 acres) of arable land, more than half of the region's area. The land is generally dry, but fertile; dryland farming, predominates. Nonetheless, there is increasing irrigation in the basins of the Douro, Pisuerga, and Tormes. About 10 percent of the region's farmland is irrigated, allowing intensive farming in those regions. Flat topography and improved communications have facilitated the entry of technical innovations throughout the agricultural production process, above all in areas such as the provinces of Valladolid and Burgos where production per hectare is among Spain's highest. Castile and León's most fertile lands are in the Esla valley of León, in the countryside of Valladolid and in the Tierra de Campos, which intersects the provinces of Zamora, Valladolid, Palencia, and León.

The region has nine DO wine zones, which are mostly located around the Duero valley.[23]

Agricultural work force

Some 92,600 people work in the primary sector in Castile and León, about 10 percent of employment in the region. 2001 data showed 5 percent unemployment in this sector.

Broken down by provinces, approximately 9,400 are employed in this sector in Ávila, 8,100 each in Burgos and Palencia, 18,300 in León, 9,200 in Salamanca, 6,400 in Segovia, 5,600 in Soria, 8,300 in Valladolid, and 14,600 in Zamora. The region's agricultural and farming sector represent 7.6% of the total in Spain.

Secondary sector (industry, mining, energy)

Industry

As of 2000, industry 18 percent of the work force of Castile and León were engaged in industry, generating 25 percent of regional GDP. The principal industrial centres are the cities of Valladolid (21,054 workers in industry), Burgos (20,217), Aranda de Duero (4,872), León (4,521) and Ponferrada (4,270).[24]

Mining

Mining has been important in Castile y León since the time of the Roman Empire, when the Roman Via de la Plata (English: "Silver Way", Spanish: Vía de la Plata) from Asturica Augusta (Astorga) to Emerita Augusta (Mérida) and Hispalis (Seville) was built to transport silver and gold mined from the deposits of las Médulas in El Bierzo.

Centuries later, after the Spanish Civil War, mining was again a factor in the economic development of the region. However, production of iron, tin, and tungsten declined notably from the 1970s onward. Coal mining (including anthracite coal) continued due to local demand for thermal power generation. Numerous Leonese mines closed in the 1980s and 1990s. Despite investments under the Mining Action Plan of the Junta of Castile and León, coal mining continues to be a troubled industry regionally.

Energy

The Douro and Ebro Rivers have numerous hydroelectric plants that make Castile and León one of Spain's leading regions in terms of power generation.

Installed hydroelectric power total 3,992 megawatts, with an annual product of 5,417 gigawatt hours. Nuclear power generates another 3,483 gigawatts per year. Thermal power from carboniferous fuels remains the region's leading source of energy, contributing 16,956 gigawatt hours for a regional total of 25,856 gigawatt hours from these major facilities. All of the nuclear power comes from the Santa María de Garoña Nuclear Power Plant in the province of Burgos, which is currently (as of 2009) expected to shut down in July 2013.

Tertiary sector (services)

63.1 percent of the work force of Castile and León is deployed in the service sector.

Tourism

Tourism highlights of the region include:[25]

- Burgos Cathedral

- León Cathedral

- Segovia, with its fortress

- The walls of Ávila

- City of Salamanca

- Sierra de Francia

Transportation

Most major surface routes from northern Spain to the capital, Madrid, and to southern Spain and Portugal, pass through Castile and León. Portugal's most important route to the east also traverses the region. As a result, Castile and León is important in the transportation network.

The major roads are Autovía A-1 (the Autovía del Norte) which runs from Madrid to the Basque port of Irun on the French border and Autovía A-6, the Autovía del Noroeste, which runs from Madrid to Arteixo, A Coruña. Also important is Autovía A-62 (the Autovía de Castilla), which comes out of Portugal through the cities of Salamanca, Valladolid, Palencia, and Burgos and continues east as part of European route E-80. Along those three routes are such important cities as Medina del Campo, Aranda de Duero, and Miranda de Ebro.

Air travel

León Airport, also known as Virgen del Camino, currently handles only domestic traffic, but hopes to handle international traffic in the future. Salamanca Airport, also known as Matacán, handles domestic flights and international charter flights. Burgos Airport, also known as Villafría, opened in July 2008. Madrid's main airport Barajas is nearby as well, although as of 2009 there is no direct connection through public transportation.

Rail

Castile and León has an extensive rail network, including the principal lines from Madrid to Cantabria and Galicia. The line from Paris to Lisbon crosses the region, reaching the Portuguese frontier at Fuentes de Oñoro in Salamanca. Astorga, Burgos, León, Miranda de Ebro, Palencia, Ponferrada,Medina del Campo and Valladolid are all important railway junctions.

Railways operate in several different gauges: Iberian gauge (1,668 mm (5 ft 5 21⁄32 in)), UIC gauge (1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in)) and Narrow gauge (1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in)). Except for some narrow-gauge lines, trains are operated by RENFE on lines maintained by the Administrador de Infraestructuras Ferroviarias (ADIF); both of these are national, state-owned companies.

Iberian gauge lines (ADIF/RENFE)

- Madrid - Irun

- Madrid - Burgos

- Castejón de Ebro - Bilbao

- Venta de Baños - A Coruña

- Palencia - Santander

- León - Gijón

- Medina del Campo - Santiago de Compostela

- Medina del Campo - Fuentes de Oñoro

- Torralba - Soria

- Villalba - Segovia

Narrow gauge

- León - Bilbao: Ferrocarril de La Robla, Europe's longest narrow-gauge line, operated by FEVE

- Cercedilla - Cotos: operated by RENFE

- Ponferrada - Villablino: operated by the Ferrocarril MSP under the Junta of Castile and León

Roads

Castile and León is the land transport hub of northern Spain. It is crossed by International E-roads E80 and E05. These are the main road connections from Portugal and the south of Spain to the rest of Europe.

The region is also crossed by two major ancient routes:

- The Way of St. James, mentioned above as a World Heritage Site, now a hiking trail and a motorway, from east to west.

- The Roman Via de la Plata ("Silver Way"), mentioned above in the context of mining, now a main road through the west of the region.

The road network is regulated by the Ley de carreteras 10/2008 de Castilla y León (Highway Law 10/2008 of Castile and León).[26] This law allows for the possibility of roads financed by the private sector through concessions, as well as the public construction of roads that has long prevailed.

Nature

Flora and vegetation

The solitary oaks and junipers now found on the Castilian-Leonese plains are remnants of forests that once covered these lands. Agricultural exploitation—cultivation of cereals and creation of pastures for the vast flocks of the Castilian Meseta—meant the deforestation of these lands during the Middle Ages. The last juniper forests of Castile and León can be found in the provinces of Soria and Burgos. In some of these forest, junipers are mixed with pine—or even with oak or gall oak—but the conifers predominate.

The Castilian-Leonese slope of the Cantabrian Mountains and the northern foothills of the Sistema Ibérico both boast rich vegetation. The cool, moist slopes are populated by large beech forests, which can extend as high as altitudes of 1,500 metres (4,900 ft). The beeches may form mixed forests with yew, rowan (mountain ash), common hawthorne, holly, and birch. The sunny slopes bring forth sessile oak, English oak, ash, common hawthorne, chestnut, birch, and pinar de Lillo (Pinus silvestris), a native pine species of northern León.

Wide extensions of oak survive on the lower slopes of the Sistema Central. Higher up, between 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) and 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) altitude, chestnuts are abundant. Nonetheless, many oak forests have disappeared, cut down and replaced by pines. The principal native pine forests are in the Sierra de Guadarrama. The subalpine zones between 1,700 metres (5,600 ft) and 2,200 metres (7,200 ft) are home to shrubs and juniper.

Much of the province of Salamanca, above all in the comarcas of Salices and Ciudad Rodrigo, is occupied by dehesas, a type of sparsely wooded land resembling the African savannas, with oak, cork oak, gall oak and Turkish oak. The provinces of Salamanca and Valladolid in the area of Rueda also have olive trees, which do not grow elsewhere in Castile and León.

Fauna

_20.jpg)

Castile and León has a great diversity of fauna. Some of these are notable either for being endemic to the region or for their rarity. 418 species of vertebrates have been identified, constituting 63 percent of the vertebrates that can be found in Spain. Animals adapted to the high mountains, inhabitant of rocky landscapes, river dwellers, lowland species, and forest animals all can be found in Castile and León.

The mountain rivers provide a habitat for nutrias and Pyrenean desmans, not to mention trout, freshwater eels, bighead carp and some increasingly rare native freshwater crabs. Mammals include the otter (Lutra lutra) and desman (Galemys pyrenaicus). In the lower depths of the river are the barbels (Barbus barbus) and carp. Local amphibians include newts, the Almanzor salamander (Salamandra salamandra almanzoris, a subspecies of fire salamander) and the Gredos toad (Bufo bufo gredosicola, a supspecies of common toad); the latter two are endemic to the Sistema Central.

Among the birds that populate the open Mediterranean forests are two endangered species: the black stork (Ciconia nigra) and the Spanish imperial eagle (also known as Iberian imperial eagle or Adalbert's eagle, Aquila adalberti).

In the coniferous forests live, among other treecreepers (of the family Certhiidae), the coal tit (Periparus ater), and the Eurasian nuthatch (Sitta europaea). The western capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) can also be found. Among the raptors in the forests are the northern goshawk, the Eurasian sparrowhawk and members of the true owl family, which frequently prey upon such smaller birds as Eurasian jays, woodpeckers (notably the great spotted woodpecker, Dendrocopos major), finches of the genus Fringilla, and warblers of the genus Sylvia.

The great bustard (Otis tarda) frequents the plains cleared for dryland farming. In the winter, the Castilian-Leonese wetlands teem with greylag geese (Anser anser), that have flown south from their breeding grounds in Northern Europe.

After many centuries disappeared from the Iberian Peninsula, the European bison is being reintroduced in Castile and Leon.[27]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "El PP renuncia a solicitar la capitalidad para evitar conflictos entre provincias" (in Spanish). El Mundo. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ↑ "Castilla y León and La Rioja". Rough Guides. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ↑ "Climate in Castilla y Leon". IberiaNature. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Elecciones Municipales 2011 (El País).

- ↑ Resultados autonómicos de Castilla y León Archived March 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. (Cinco Días).

- ↑ "será objeto de protección específica [...] por su particular valor dentro del patrimonio lingüístico de la Comunidad"

- ↑ "gozará de respeto y protección en los lugares en que habitualmente se utilice"

- ↑ Hablas de Extremadura: Frontera Leonesa.

- ↑ "Castilla y Leon travel guide". Insight Guides. Apa Publications. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Artículo 1, Proyecto Constitución Federal de la I República Española, 17 de julio de 1873

- ↑ Investigaciones históricas. Valladolid: Secretariado de Publicaciones, Universidad de Valladolid, 1979

- ↑ Juan-Miguel Alvarez Dominguez, "El Catecismo Regionalista de Don Eugenio, un ejemplo de regionalismo castellanoleonés patrocinado desde León (1931)", Argutorio, nº 19 (2º semestre 2007), pp. 32-36.

- ↑ «unir en una personalidad a León y Castilla la Vieja en torno a la gran cuenca del Duero, sin caer ahora en rivalidades pueblerinas». Diario de León, 22 de mayo de 1936.

- ↑ "Seis grupos políticos se fusionan en un partido regionalista en Castilla y León". Elpais.com. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ↑ Tribunal Constitucional Española, Sentencia 89/1984, fundamento de derecho 5, September 28, 1984.

- ↑ Diario de León, 5 de mayo de 1984.

- ↑ Diario de León, 13 de marzo de 2004.

- ↑ National Statistics Institute

- ↑ Ribeiro, Ana Isabel; Krainski, Elias Teixeira; Carvalho, Marilia Sá; Pina, Maria de Fátima de (2016-02-15). "Where do people live longer and shorter lives? An ecological study of old-age survival across 4404 small areas from 18 European countries". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health: jech–2015–206827. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-206827. ISSN 1470-2738. PMID 26880296.

- ↑ "Castilla y Leon". Internal Market, Industry. European Commission. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ El paro bajó en Castilla y León un 5% frente a un incremento nacional del 6,5, El Mundo, 2008-01-26. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ El paro sube en la Comunidad en 5.000 personas en el segundo trimestre, rtvcyl.es, 2009-07-24. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ "Castilla y Leon wines". Wine-Searcher. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ↑ Fichas Municipales - 2008 DATOS ECONÓMICOS Y SOCIALES, Caja España, 2008. Archived December 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Introducing Castilla y León". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ↑ Ha entrado en vigor la nueva Ley de carreteras de Castilla y León que regula la planificación, proyección, construcción, conservación, financiación, uso y explotación de las carreteras con itinerario comprendido íntegramente en el territorio de la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla y León y que no sean de titularidad del Estado.

- ↑ http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2010/06/04/castillayleon/1275667194.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Castile and León. |

- Cortes de Castilla y León (Regional Parliament) (Spanish)

- Junta de Castilla y León (Regional Government) (Mostly in Spanish)

- The Cortes of Castile-León, Joseph F. O'Callaghan (historical)

- Tourist Information