Châtelperronian

| Geographical range | Afro-Eurasia |

|---|---|

| Period | Upper Paleolithic |

| Dates | 41,030 – 39,260 cal BP[1] |

| Type site | La Grotte des Fées |

| Major sites | Châtelperron |

| Preceded by | Mousterian |

| Followed by | Aurignacian |

| The Paleolithic |

|---|

|

↑ Pliocene (before Homo) |

|

Lower Paleolithic

Middle Paleolithic

Upper Paleolithic

|

| ↓ Mesolithic ↓ Stone Age |

Châtelperronian was the earliest industry of the Upper Palaeolithic in central and south western France, extending also into Northern Spain. It derives its name from the site of la Grotte des Fées, in Châtelperron, Allier, France.

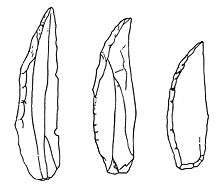

It arose from the earlier Mousterian industry. It lasted from between c. 45,000 and c. 40,000 BP.[1] The industry produced denticulate stone tools and also a distinctive flint knife with a single cutting edge and a blunt, curved back. The use of ivory at Châtelperronian sites tends to be more frequent than that of the later Aurignacian,[2] while antler tools appear to be absent.

It was followed by the Aurignacian industry. Controversy exists as to how far archaeologically it is associated with Neanderthal people.[3][4] The Châtelperronian industry may relate to the origins of the very similar Gravettian culture. French archaeologists have traditionally classified both cultures together under the name Périgordian, Early Perigordian being equivalent to Châtelperronian and all the other phases corresponding to Gravettian,[5][6][7] though this scheme is not often used by Anglophone authors.

Important sites and lithic production and associations

Large thick flakes/small blocks were used for cores, and were prepared with a crest over a long smooth surface. Using one or two striking points, long thin blades were detached. Direct percussion with a soft hammer was likely used for accuracy. Thicker blades made in this process were often converted into side scrapers, burins were often created in the same manner from debitage as well.

The manner of production is a solid continuation of the Mousterian but the ivory adornments found in association seem to be a more clear connection to Aurignacian peoples,[2] who are often argued to be the earliest introduction of H. sapiens sapiens into Europe. The technological refinement of the Châtelperronian and neighbouring Uluzzian in Central-Southern Italy is often argued to be the product of cultural influence from H. sapiens sapiens that lived nearby, but these predate both the Aurignacian and the earliest presence of H. sapiens sapiens in Europe.

Dispute over disruption of the site

João Zilhão and colleagues argue that the findings are complicated by disturbance of the site in the 19th century, and conclude that the apparent pattern of Aurignacian/Châtelperronian inter-stratification is an artifact of disturbance.[8] · [9] Bordes and Teyssandier (2011) further support this assertion. They claim post-depositional processes are behind the inter-stratification of Chatelperronian and Aurignacian material, a claim they back up by citing numerous open-air Chatelperronian sites without any evidence of Middle-Paleolithic layers below.[10]Paul Mellars and colleagues have criticized Zilhão et al.'s analysis, and argue that the original excavation by Delporte was not affected by disturbance.[11]

Paul Mellars, however, now has concluded on the basis of new radiocarbon dating on the cave of Grotte du Renne [3] "that there was strong possibility—if not probability— that they were stratigraphically intrusive into the Châtelperronian deposits from .. overlying Proto-Aurignacian levels" and that "The central and inescapable implication of the new dating results from the Grotte du Renne is that the single most impressive and hitherto widely cited pillar of evidence for the presence of complex “symbolic” behavior among the late Neanderthal populations in Europe has now effectively collapsed."[4] More recent research led by Jean-Jacques Hublin of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany shows using new new high precision dates that Châtelperronian tools were produced by neanderthals. In Sept 2016, researchers using a proteinomic approach to the fossils have determined conclusive that Châtelperronian tools were produced by neanderthals.

In popular culture

Author Jared Diamond argues in his 1991 non-fiction book, The Third Chimpanzee, that Châtelperron may represent a community of Neanderthals who had to some extent adopted the culture of the modern Homo sapiens that had established themselves in the surrounding area, which would account for the signs of a hybrid culture found at the site. Diamond compares these hypothetical Neanderthal hold-outs to more recent Native Americans in North and South America who adopted European technologies such as firearms or domestication of horses in order to survive in an environment dominated by technologically more-advanced competitors.[12]

The fifth book of Jean Auel's Earth's Children series, The Shelters of Stone, 2002, and the sixth book The Land of the Painted Caves 2010 are set in this region of modern-day France, during this period.

See also

| Preceded by Mousterian |

Châtelperronian 35,000–29,000 BP |

Succeeded by Aurignacian |

References

- 1 2 "The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance". Nature. Nature.com. 512: 306–309. Aug 2014. doi:10.1038/nature13621. PMID 25143113. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- 1 2 d'Errico, F.D., Zilhao, J., Julien, M., Baffier, D. and Pelerin, J. 1998. Neanderthal Acculturation in Western Europe? A Critical Review of the Evidence and its Interpretation. Current Anthropology Supplement to 39: S1-S44

- 1 2 Higham T, Jacobi R, Julien M, David F, Basell L, Wood R, Davies W, Ramsey CB.C (2010). Chronology of the Grotte du Renne (France) and implications for the context of ornaments and human remains within the Chatelperronian. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1007963107 PMID 20956292

- 1 2 Mellars P. (2010). Neanderthal symbolism and ornament manufacture: The bursting of a bubble? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014588107

- ↑ F. Jordá Cerdá et al., Historia de España 1. Prehistoria. Gredos ed. 1986. ISBN 84-249-1015-X

- ↑ X. Peñalver, Euskal Herria en la Prehistoria. Orain ed. 1996. ISBN 84-89077-58-4

- ↑ M.H. Alimen and M.J. Steve, Prehistoria. Siglo XXI ed. 1970. ISBN 84-323-0118-3

- ↑ Zilhão, João; Francesco d’Errico; Jean-Guillaume Bordes; Arnaud Lenoble; Jean-Pierre Texier; Jean-Philippe Rigaud (2006). "Analysis of Aurignacian interstratification at the Châtelperronian-type site and implications for the behavioral modernity of Neandertals". PNAS. 103 (33): 12643–12648. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10312643Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605128103. PMC 1567932

. PMID 16894152.

. PMID 16894152. - ↑ Zilhão, João; et al. (2008). "Like Hobbes' Chimney Birds" (PDF). PaleoAnthropology: 65–67.

- ↑ Bordes, J; N Teyssandierl. (2011). "The Upper Paleolithic nature of the Châtelperronian in South-Western France: Archeostratigraphic and lithic evidence". Quaternary International. 246: 382–388. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.08.001.

- ↑ Mellars, Paul; Brad Gravina; Christopher Bronk Ramsey (2007). "Confirmation of Neanderthal/modern human interstratification at the Chatelperronian type-site". PNAS. 104 (9): 3657–3662. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.3657M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608053104. PMC 1805566

. PMID 17360698.

. PMID 17360698. - ↑ F. Jared Diamond, The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal Harper Perennial. 2006. ISBN 978-0-06-084550-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Châtelperronian. |

- Picture Gallery of the Paleolithic (reconstructional palaeoethnology), Libor Balák at the Czech Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Archaeology in Brno, The Center for Paleolithic and Paleoethnological Research