Chavacano

| Chavacano | |

|---|---|

| Chavacano | |

| Native to | Philippines |

| Region | Zamboanga |

| Ethnicity |

Zamboangueño people Filipinos in Indonesia Filipinos in Malaysia |

Native speakers | 1.2 million (1996)[1] |

|

Spanish Creole

| |

| Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Recognized regional language of the Philippines Zamboanga City (official language) and Basilan (lingua franca) |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

cbk |

| Glottolog |

chav1241[2] |

| Linguasphere |

51-AAC-ba |

|

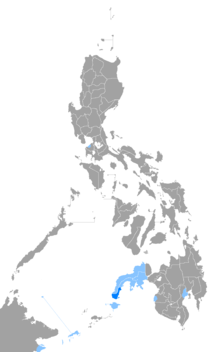

Area where Chavacano is spoken | |

Chavacano or Chabacano [tʃaβaˈkano] is a Spanish-based creole language spoken in the Philippines. The word Chabacano is derived from Spanish, meaning "poor taste", "vulgar", for the Chavacano language, developed in Cavite City, Ternate, Zamboanga and Ermita.

Six different dialects have developed: Zamboangueño in Zamboanga City, Davaoeño Zamboangueño / Castellano Abakay in Davao City, Ternateño in Ternate, Cavite, Caviteño in Cavite City, Cotabateño in Cotabato City and Ermiteño in Ermita.

Chavacano is the only Spanish-based creole in Asia. It has survived for more than 400 years, making it one of the oldest creole languages in the world. Among Philippine languages, it is the only one not an Austronesian language, but like Malayo-Polynesian languages, it uses reduplication.

Dialects

This creole has six dialects. Their classification is based on their substrate languages and the regions where they are commonly spoken. The three known dialects of Chavacano with Tagalog as their substrate language are the Luzon-based creoles of which are Caviteño (spoken in Cavite City), Bahra or Ternateño (spoken in Ternate, Cavite) and Ermiteño (once spoken in the old district of Ermita in Manila and is now extinct).

Zamboangueño Chavacano emanated from Caviteño Chavacano as evidenced by prominent Zamboangueño families who descended from Spanish Army officers (from Spain and Latin America), primarily Caviteño mestizos, stationed at Fort Pilar in the 19th century. When Caviteño officers recruited workers and technicians from Iloilo to man their sugar plantations and rice fields to reduce the local population's dependence on the Donativo de Zamboanga, taxes levied by the Spanish colonial government on the islanders to support the fort's operations. With the subsequent migration of Ilonggo traders to Zamboanga, the Zamboangueño Chavacano was infused with Ilonggo words as the previous migrant community was assimilated.

Most of what appears to be Cebuano words in Zamboangueño Chavacano are actually Ilonggo. Although Zamboangueño Chavacano's contact with Cebuano began much earlier when Cebuano soldiers were stationed at Fort Pilar during the Spanish colonial period, it was not until closer to the middle of the 20th century that borrowings from Cebuano accelerated from more migration from the Visayas as well as the current migration from other Visayan-speaking areas of the Zamboanga Peninsula.

Zamboangueño(chavacano) is spoken in Zamboanga City, Basilan Province, parts of Sulu Province and Tawi-Tawi Province, and in Semporna-Sabah, Malaysia, and Zamboanga del Sur, Zamboanga Sibugay and Zamboanga del Norte. The other dialects of Chavacano with Cebuano as their primary substrate language are the Mindanao-based creoles of which are Castellano Abakay or Chavacano de Davao (spoken in some areas of Davao), it has an influence from Chinese and Japanese, also divided into two subdalects, Castellano Abakay Chino and Castellano Abakay Japón, and Cotabateño (spoken in Cotabato City). Both Cotabateño and Davaoeño evolved from Zamboangueño.

Native speakers and dialects

| Chavacano dialects | Places | Native speakers |

|---|---|---|

| Zamboangueño (Zamboangueño/Zamboangueño Chavacano/Chabacano de Zamboanga) | Zamboanga City, Basilan Province, Sulu Province, Tawi-Tawi Province, Zamboanga del Sur, Zamboanga del Norte, Zamboanga Sibugay, Cagayan de Oro, Semporna, Sabah, | 689 000[3] |

| Caviteño (Chabacano di Nisos/Chabacano de Cavite) | Cavite City | 200 000 |

| Cotabateño (Chabacano de Cotabato) | Cotabato City, Maguindanao, SOCCSKSARGEN | 20 500 |

| Castellano Abakay (Chabacano de Davao) | Davao Region, Davao City | 18 000 |

| Ternateño (Bahra) | Ternate | 7000 |

| Ermiteño (Ermitense) | Ermita District | Extinct |

Characteristics

The Chavacano languages in the Philippines are creoles based on Mexican Spanish and Portuguese. In some Chavacano languages, most words are common with Andalusian Spanish, but there are many words borrowed from Nahuatl, a language native to Central Mexico, which are not to be found in Andalusian Spanish. Although the vocabulary is largely Mexican, its grammar is mostly based on other Philippine languages, primarily Ilonggo, Tagalog and Cebuano. Its vocabulary also has influences from Italian, Portuguese and the Native American languages Nahuatl, Taino, Quechua, etc. as can be evidenced by the words chongo (monkey, instead of Spanish 'mono'), tiange (mini markets), etc. The vocabulary of the Ternateño dialect, in particular, has a major influence from the Portuguese language and the language of Ternate in Indonesia since the speakers of the said dialect are the descendants of the Indonesian soldiers brought by the Spaniards in the area. This can be seen in the use of the word 'na' instead of the Spanish 'en'.

In contrast with the Luzon-based creoles, the Zamboangueño dialect has the most borrowings and/or influence from other Philippine Austronesian languages including Hiligaynon, Subanen/Subanon, Bangingi, Sama, Tausug, Yakan, Tagalog, Ilocano and Malay origin are present in Zamboangueño dialect; the latter is included because although not local in Philippines, it was the lingua franca of maritime Southeast Asia. As Zamboangueño dialect is also spoken by Muslims, the dialect has some Arabic loanwords, most commonly Islamic terms. Nevertheless, it is difficult to trace whether these words have their origin in the local population or in Spanish itself, given that Spanish has about 6,000 words of Arabic origin. Chavacano also contains loanwords of Persian origin which enter Chavacano via Malay and Arabic; both Persian and Spanish are Indo-European languages.

Demographics

The highest number of Chavacano speakers are found in Zamboanga City and in the island province of Basilan. A significant number of Chavacano speakers are found in Cavite City and Ternate. There are also speakers in some areas in the provinces of Zamboanga del Sur, Zamboanga Sibugay, Zamboanga del Norte, Davao, and in Cotabato City. According to the official 2000 Philippine census, there were altogether 607,200 Chavacano speakers in the Philippines in that same year. The exact figure could be higher as the 2000 population of Zamboanga City, whose main language is Chavacano, far exceeded that census figure. Also, the figure does not include Chavacano speakers of the Filipino diaspora. Notwithstanding, Zamboangueño is the dialect with the most number of speakers, being the official language of Zamboanga City whose population is now believed to be over a million; is also an official language in Basilan.

Speakers can also be found in the town of Semporna in the eastern coast of Sabah, Malaysia—not surprisingly—because this northern part of Borneo is close to the Sulu islands and the Zamboanga Peninsula. Chavacano speakers are possibly found elsewhere in Sabah as Sabah was under partial Spanish sovereignty and via Filipino refugees who escaped from Zamboanga Peninsula and predominantly Muslim areas of Mindanao like Sulu Archipelago.

A small number of Zamboanga's indigenous peoples and of Basilan, such as the Tausugs, the Samals, and the Yakans, majority of those people are Sunni Muslims, also speak the language. In the close provinces of Sulu and Tawi-Tawi areas, there are Muslim speakers of the Chavacano de Zamboanga, all of them are neighbors of Christians. Speakers of the Chavacano de Zamboanga, both Christians and Muslims, also live in Lanao del Norte and Lanao del Sur. Christians and Muslims in Maguindanao, Sultan Kudarat, Cotabato, South Cotabato, Cotabato City, and Saranggani speak Chavacano de Zamboanga, while some of those living in Davao Region speak Chavacano de Davao. Take note that Zamboanga Peninsula, Basilan, Sulu, Tawi-tawi, Maguindanao, Cotabato City, SOCCSKSARGEN (region that composed of Sultan Kudarat, Cotabato, South Cotabato, and Saranggani) and Davao Region became part of short-lived Republic of Zamboanga, which chose Chavacano as official language.

Social significance

Chavacano has been primarily and practically a spoken language. In the past, its use in literature was limited and chiefly local to the geographical location where the particular variety of the language was spoken. Its use as a spoken language far exceeds its use in literary work in comparison to the use of Spanish in the Philippines which was more successful as a written language than a spoken language. In recent years, there have been efforts to encourage the use of Chavacano as a written language, but the attempts were mostly minor attempts in folklore and religious literature and few pieces of written materials by the print media. In Zamboanga City, while the language is used by the mass media, the Catholic Church, education, and the local government, there have been few literary work written in Zamboangueño and access to these resources by the general public is not readily available. As Chavacano is spoken by Muslims as second language not only in Zamboanga City and Basilan but even in Sulu and Tawi-tawi, a number of Qur'an books are published in Chavacano.

While the Mindanao-based creoles, Castellano Abakay, and Cotabateño are believed to be in danger of extinction, the Zamboangueño dialect has been constantly evolving especially during half of the past century until the present. Zamboangueño has been experiencing an infusion of English and more Tagalog words and from other languages worldwide in its vocabulary and there have been debates and discussions among older Chavacano speakers, new generation of Chavacano speakers, scholars, linguists, sociologists, historians, and educators regarding its preservation, cultivation, standardisation, and its future as a Spanish-based creole. In 2000, The Instituto Cervantes in Manila hosted a conference entitled "Shedding Light on the Chavacano Language" at the Ateneo de Manila University.

Because of the grammatical structures, Castilian usage, and archaic Spanish words and phrases that Chavacano (especially Zamboangueño) uses, between speakers of both contemporary Spanish and Chavacano who are uninitiated, both languages appear to be non-intelligible to a large extent. For the initiated speakers, Chavacano can be intelligible to some Spanish speakers, and while most Spanish words can easily be understood by Chavacano speakers, many would struggle to understand a complete Spanish sentence.

Etymology

Chavacano or Chabacano originated from the Spanish word chabacano which literally means "poor taste", "vulgar", "common", "of low quality", or "coarse", meanings that have been reclaimed by modern Chabacano speakers. During the Spanish colonial period, it was called by the Spanish-speaking population as the "lenguaje de la calle", "lenguaje de parian" (language of the street), or "lenguaje de cocina" (kitchen Spanish to refer to the Chabacano spoken by the people of Manila, particularly in Ermita) to distinguish it from the Spanish language spoken by the peninsulares, insulares, mestizos, or the elite class called the ilustrados. This common name has evolved into a word of its own in different spellings with no negative connotation, but to simply mean as the name of the language with that distinct Spanish flavour. However, most of its earlier speakers were born of mixed parentage – Hispanized urbane natives, Chinese migrants and Spanish or Latin American soldiers and civil servants during the Spanish colonial period.

Orthography

Zamboangueños usually, though not always, spell the name of their native language as Chavacano to refer to their language while to themselves who speak the Zamboangueño Dialect of the Chavacano Language as Zamboangueño, and they spell the word as Chabacano referring to the original Spanish meaning of the word or as Chabacano referring also to the language itself. Thus, Zamboangueños generally spell the name of their language in two different ways but the most preferred is "Chavacano".

Caviteños, Ternateños, and Ermitenses spell the word as it is spelled originally in the Spanish language – as Chabacano. Davaoeños (Castellano Abakay), Cotabateños, and especially those from Basilan province tend to use the Zamboangueño spellings. The dialects of the language are geographically related: Ermitense, Caviteño, and Ternateño – also known as Bahra – are similar to each other in having Tagalog as their substrate language while Zamboangueño, Castellano Abakay, and Cotabateño are similar to each other in having Visayan (mostly Cebuano, Tausug, and Hiligaynon), Subanon, and Sama as their substrate language(s). Zamboangueños would call their dialect Zamboangueño, Zamboangueño Chavacano, and Caviteños would call their dialect Caviteño or Chabacano de Cavite, etc., to emphasize the difference between their dialect and others using their own geographical location as a point of reference.

There are also other alternative names and spellings for this language depending on the dialects and context (whether Hispanicized or native). Zamboangueños sometimes spell their dialect as Chavacano, or Zamboangenio. Caviteño is also known as Caviten, Linguaje di Niso, or sometimes spell their dialect as Tsabakano. Ermitense is also known as Ermiteño while Ternateño is also known as Ternateño Chabacano, Bahra, or Linguaje di Bahra. Davaoeño is also Davaweño, Davawenyo, Davawenyo Zamboangenyo, Castellano Abakay, or Davao Chabacano/Chavacano. Cotabateño is also known as Cotabato Chabacano/Chavacano.

Speakers from Basilan consider their Chavacano as Zamboangueño or formally as Chavacano de Zamboanga.

Historical development

Zamboangueño

On 23 June 1635, Zamboanga City became a permanent foothold of the Spanish government with the construction of the San José Fortress. Bombardment and harassment from pirates and raiders of the sultans of Mindanao and Jolo and the determination to spread Christianity further south (as Zamboanga was a crucial strategic location) of the Philippines forced the Spanish missionary friars to request reinforcements from the colonial government.

The military authorities decided to import labor from Luzon and the Visayas. Thus, the construction workforce eventually consisted of Spanish and Mexican soldiers, masons from Cavite (who comprised the majority), sacadas from Cebu and Iloilo, and those from the various local tribes of Zamboanga like the Samals and Subanons.

Language differences made it difficult for one ethnic group to communicate with another. To add to this, work instructions were issued in Spanish. The majority of the workers were unschooled and therefore did not understand Spanish but needed to communicate with each other and the Spaniards. A pidgin developed and became a full-fledged creole language still in use today as a lingua franca and/or as official language, mainly in Zamboanga City.

When Sultanate of Sulu gave up its territories Sulu Archipelago to Spain within late 1700s (Sulu Sultanate gave up Basilan to Spain in 1762, while Sulu and Tawi-tawi were not given up by sultanate because Sulu Sultanate only recognized partial Spanish sovereignty to Sulu and Tawi-tawi), Spanish settlers and soldiers brought the language to the region until Spain, Germany, and United Kingdom signed an agreement named Madrid Protocol of 1885 that recognized Spanish rule of Sulu Archipelago. Chavacano becomes a lingua franca of Sulu Archipelago (composing of Sulu, Tawi-tawi, Basilan); although North Borneo (now Sabah) isn't included on the Spanish East Indies area as stated on the Protocol and control by the United Kingdom, Chavacano has still a little impact in the Semporna town.

From then on, constant Spanish military reinforcements as well as increased presence of Spanish religious and educational institutions have fostered the Spanish creole.

Caviteño / Ternateño

The Merdicas (also spelled Mardicas or Mardikas) were Catholic natives of the islands of Ternate and Tidore of the Moluccas, converted during the Portuguese occupation of the islands by Jesuit missionaries. The islands were later captured by the Spanish who vied for their control with the Dutch. In 1663, the Spanish garrison in Ternate were forced to pull out to defend Manila against an impending invasion by the Chinese pirate Koxinga (sacrificing the Moluccas to the Dutch in doing so). A number of Merdicas volunteered to help, eventually being resettled in a sandbar near the mouth of the Maragondon river (known as the Barra de Maragondon) and Tanza, Cavite, Manila.[4]

The invasion did not occur as Koxinga fell ill and died. The Merdicas community eventually integrated into the local population. Today, the place is called Ternate after the island of Ternate in the Moluccas, and the descendants of the Merdicas continue to use their Spanish creole (with Portuguese influence) which came to be known as Caviteño or Ternateño Chavacano.[4]

Samples

Zamboangueño

- Donde tu hay anda?

- Spanish: ¿A dónde vas?

- (‘Where are you going?’)

- Ya mirá yo con José.

- Spanish: Yo vi a José.

- (‘I saw José.’)

- Ya empezá ele buscá que buscá entero lugar con el sal.

- Spanish: El/Ella empezó a buscar la sal en todas partes.

- (‘He/She began to search everywhere for the salt.’)

- Ya andá ele na escuela.

- Spanish: El/Ella se fue a la escuela.

- (‘He/She went to school.’)

- Si Mario ya dormí na casa.

- Spanish: Mario durmió en la casa.

- (‘Mario slept in the house.’)

- El hombre, con quien ya man encuentro tu, amo mi hermano.

- Spanish: El hombre que encontraste, es mi hermano.

- (The man [whom] you met is my brother.)

- El persona con quien tu tan cuento, bien alegre gayot.

- Spanish: La persona con quien estás hablando es muy alegre. / La persona con quien tú estás conversando es bien alegre.

- (The person you are talking to is very happy indeed.)

Another sample of Zamboangueño Chavacano

|

Zamboangueño Chavacano: Treinta y cuatro kilometro desde el pueblo de Zamboanga el Bunguiao, un diutay barrio que estaba un desierto. No hay gente quien ta queda aquí antes. Abundante este lugar de maga animales particularmente maga puerco 'e monte, gatorgalla, venao y otro más pa. Solamente maga pajariadores lang ta visitá con este lugar. |

Spanish: El Bunguiao, a treinta y cuatro kilómetros desde el pueblo de Zamboanga, es un pequeño barrio que una vez fue un área salvaje. No había gente que se quedara a vivir ahí. En este lugar había en abundancia animales salvajes tales como cerdos, gatos monteses, venados, y otros más. Este lugar era visitado únicamente por cazadores de pájaros. |

English: Bunguiao, a small village, thirty four kilometers from the city of Zamboanga, was once a wilderness. No people lived here. The place abounded with wild animals such as pigs, wildcats, deer, and still others. The place was visited only by bird hunters. |

Ermitaño

- En la dulzura de mi afán,

- Junto contigo na un peñon

- Mientras ta despierta

- El buan y en

- Las playas del Pasay

- Se iba bajando el sol.

- Yo te decía, "gusto ko"

- Tu me decías, "justo na"

- Y de repente

- ¡Ay nakú!

- Ya sentí yo como si

- Un asuáng ta cercá.

- Que un cangrejo ya corré,

- Poco a poco na tu lao.

- Y de pronto ta escondé

- Bajo tus faldas, ¡amoratáo!

- Cosa que el diablo hacé,

- Si escabeche o kalamáy,

- Ese el que no ta sabé

- Hasta que yo ya escuché

- Fuerte-fuerte el voz: ¡Aray!

A sample of Ermitaño from a book called Pidgins and Creoles by John Holm. The text was taken from a linguist named Whinnom in 1956. The book said there were 15,000 speakers in 1942 in Ermita, but almost all are gone.

Ta sumí el sol na fondo del mar, y el mar, callao el boca. Ta jugá con su mana marejadas com'un muchacha nerviosa con su mana pulseras. El viento no mas el que ta alborota, el viento y el pecho de Felisa que ta lleno de sampaguitas na fuera y lleno de suspiros na dentro.

Caviteño / Ternateño

- Nisós ya pidí pabor cun su papang.

- Spanish: Nosotros ya pedimos un favor de tu padre.

- (We have already asked your father for a favor.)

Another sample of Chavacano de Cavite

|

Chavacano de Cavite: Puede nisos habla: que grande nga pala el sacrificio del mga héroe para niso independencia. Debe nga pala no niso ulvida con ilos. Ansina ya ba numa? Debe haci niso mga cosa para dale sabi que ta aprecia niso con el mga héroe. Que preparao din niso haci sacrificio para el pueblo. Que laya? Escribi mga novela como Jose Rizal? |

Spanish: Nosotros podemos decir qué grandes sacrificios ofrecieron nuestros héroes para obtener nuestra independencia. Entonces, no nos olvidemos de ellos. ¿Como lo logramos? Necesitamos hacer cosas para que sepan que apreciamos a nuestros héroes; que estamos preparados tambien a sacrificar por la nación. ¿Cómo lo haremos? ¿Hay que escribir también novelas como José Rizal? |

English: We can say what great sacrifices our heroes have done to achieve our independence. We should therefore not forget them. Is it like this? We should do things to let it be known that we appreciate the heroes; that we are prepared to make sacrifices for our people. How? Should we write novels like José Rizal? |

Castellano Abakay (Chabacano de Davao)

Below are samples of dialogues and sentences of Chabacano de Davao in two spoken forms: Castellano Abakay Chino (Chinese style) by the Chinese speakers of Chabacano and Castellano Abakay Japon (Japanese style) by the Japanese speakers.

Castellano Abakay Chino

- Note: only selected phrases are given with Spanish translations, some are interpretations and rough English translations are also given.

- La Ayuda

- Ayudante: Señor, yo vino aquí para pedir vos ayuda.

- (Spanish: Señor, he venido aquí para pedir su ayuda.)

- (English: Sir, I have come here to ask for your help.)

- Patron: Yo quiere prestá contigo diez pesos. Ese ba hija tiene mucho calentura. Necesita llevá doctor.

- (Spanish: Quiero darle diez pesos. Su hija tiene calentura. Necesita un médico.)

- (English: I want to give you ten pesos. Your daughter has fever. You need a doctor.)

- Valentina y Conching (Conchita)

- Valentina: ¿¡Conching, dónde vos (tu) papá?! ¿No hay pa llegá?

- Spanish: ¿¡Conching, dónde está tu papá?! ¿No ha llegado todavía?

- English: Conching, where is your dad? Hasn't he arrived yet?

- Conching: Llegá noche ya. ¿Cosa quiere ako (yo) habla cuando llegá papa?

- Spanish: Llegará esta noche. ¿Qué quiere que le diga cuando llegue?

- English: He will arrive this evening. What do you want me to tell him when he comes?

- Ako (yo) habla ese esposa mio, paciencia plimelo (primero). Cuando male negocio, come nugaw (lugaw – puré de arroz). Pero, cuando bueno negocio, katay (carnear) manok (pollo).

- Spanish: Me limitaré a decir a mi esposa, mis disculpas. Cuando nuestro negocio va mal, comemos gachas. Pero si funciona bien, carneamos y servimos pollo.

- English: I will just tell my wife, my apologies. We ate congee when our business goes very badly. But if it goes well, then we will slay and serve chicken.

- ¡Corre pronto! Cae aguacero ! Yo habla contigo cuando sale casa lleva payong (paraguas). No quiere ahora mucho mojao.

- Spanish: ¡Corre rápido! ¡La lluvia está cayendo! Ya te dije que cuando salgas de tu casa, debes llevar un paraguas. No quiero que te moje.

- English: Run quickly! The rain is falling! I already told you to take an umbrella when you leave the house. I don't want you to get wet.

- ¿Ese ba Tinong (Florentino) no hay vergüenza? Anda visita casa ese novia, comé ya allí. Ese papa de iya novia, regaña mucho. Ese Tinong, no hay colocación. ¿Cosa dale comé esposa después?

- Spanish: ¿Que Florentino no tiene vergüenza? Fue a visitar a su novia, y comió allí. El padre de su novia, regañarlo mucho. Florentino no tiene trabajo. ¿Qué le proveerá a su esposa después?

- English: Doesn't Florentino have any shame? He went to visit his girlfriend and ate dinner there. Her father quarrels a lot. That Florentino has no job. What will he provide to his wife then?

Castellano Abakay Japon

Estimated English translations provided with Japanese words.

- ¿Por qué usted no andá paseo? Karâ tiene coche, viaje usted. ¿Cosa hace dinero? Trabaja mucho, no gozá.

- Why don't you go for a walk? You travel by your car. What makes money? You work a lot, you don't enjoy yourself.

- Karâ (から) – por (Spanish); from or by (English)

- Usted mirá porque yo no regañá ese hijo mío grande. Día-día sale casa, ese ba igual andá oficina; pero día-día pide dinero.

- Look because I don't tell off that big son of mine. Every day he leaves the house, the same for walking to the office; but every day he asks for money.

- Señora, yo dale este pescado usted. No grande, pero mucho bueno. Ese kirey y muy bonito. (Op.cit.)

- Madame, I give this fish to you. It's not big, but it's very good. It is bonny and very nice.

- Kirei (綺麗) – hermosa, "bonita" (Spanish); beautiful, bonny (English)

Zamboangueño

- Yo (soy) un Filipino.

- Yo ta prometé mi lealtad

- na bandera de Filipinas

- y el País que ese ta representá

- Con Honor, Justicia y Libertad

- que ya pone na movemiento el un nación

- para Dios,

- para'l pueblo,

- para naturaleza,

- y para Patria.

English

- I am a Filipino

- I pledge my allegiance

- To the flag of the Philippines

- And to the country it represents

- With honor, justice and freedom

- Put in motion by one Nation

- For God

- for the People,

- for Nature and

- for the Country.

Vocabulary

Forms and style

Chavacano (especially Zamboangueño) has two registers or sociolects: The common, colloquial, vulgar or familiar and the formal register/sociolects.

In the common, colloquial, vulgar or familiar register/sociolect, words of local origin or a mixture of local and Spanish words predominate. The common or familiar register is used ordinarily when conversing with people of equal or lower status in society. It is also used more commonly in the family, with friends and acquaintances. Its use is of general acceptance and usage.

In the formal register/sociolect, words of Spanish origin or Spanish words predominate. The formal register is used especially when conversing with people of higher status in society. It is also used when conversing with elders (especially in the family and with older relatives) and those in authority. It is more commonly used by older generations, by Zamboangueño mestizos, and in the barrios. It is the form used in speeches, education, media, and writing. The formal register used in conversation is sometimes mixed with some degree of colloquial register.

The following examples show a contrast between the usage of formal words and common or familiar words in Chavacano:

| English | Chavacano (Formal) | Chavacano (Common/Colloquial/Vulgar/Familiar) | Spanish |

|---|---|---|---|

| slippery | resbalozo/resbaladizo | malandug | resbaladizo |

| rice | morisqueta | kanon/arroz | arroz |

| rain | lluvia/aguacero | aguacero/ulan | aguacero/lluvia |

| dish | vianda/comida | comida/ulam | vianda/comida |

| braggart/boastful | orgulloso(a) | bugalon(a)/ hambuguero(a) | orgulloso(a) |

| car | coche | auto | coche/auto |

| housemaid | muchacho (m)/muchacha (f) | ayudanta (female); ayudante (male) | muchacha(o)/ayudante |

| father | papá (tata) | pápang (tata) | papá (padre) |

| mother | mamá (nana) | mámang (nana) | mamá (madre) |

| grandfather | abuelo | abuelo/lolo | abuelo/lolo |

| grandmother | abuela | abuela/lola | abuela/lela |

| small | chico(a)/pequeño(a) | pequeño(a)/diutay | pequeño/chico |

| nuisance | fastidio | asarante / salawayun | fastidio |

| hard-headed | testarudo | duro cabeza/duro pulso | testarudo |

| slippers | chancla | chinelas | chancla/chinelas |

| married | de estado/de estao | casado/casao | casado |

| (my) parents | (mis) padres | (mi) tata'y nana | (mis) padres |

| naughty | travieso(a) | guachi / guachinanggo(a) | desagradable |

| slide | rezbalasa/deslizar | landug | resbalar/deslizar |

| ugly | feo (masculine)/fea (feminine) | malacara, malacuka | feo(a) |

| rainshower | lluve | talítih | lluvia |

| lightning | rayo | rayo/quirlat | rayo |

| thunder/thunderstorm | trueno | trueno | trueno |

| tornado | tornado/remolino, remulleno | ipo-ipo | tornado/remolino |

| thin (person) | delgado(a)/flaco(a)/chiquito(a) | flaco/flaquit | delgado/flaco |

Orthography

Chavacano orthography

Chavacano words of Spanish origin are written using the Latin script with some special characters from the Spanish alphabet: the vowels with the acute accent (á, é, í, ó, ú), the vowel u with trema (ü), and ñ.

Chavacano words of local origin are spelled in the manner according to their origin. Thus, the letter k appear mostly in words of Austronesian origin or in loanwords from other Philippine languages (words such as kame, kita, kanamon, kaninyo).

Some additional characters like the ñ (eñe, representing the phoneme /ɲ/, a letter distinct from n but typographically composed of an n with a tilde), the digraph ch (che, representing the phoneme /tʃ/), the ll (elle, representing the phoneme /ʎ/), and the digraph rr (erre with strong r) exist in Chavacano.

The Chavacano alphabet has 30 letters, including the special characters.

As a general rule, words of Spanish origin are written and spelled using Spanish orthography (fiesta, casa). Words of local (Philippine languages) origin are written and spelled using local orthography only when those words are pronounced in the local manner (manok, kanon). Otherwise, words of local origin are written and spelled in the native manner along Spanish spelling rules (jendeh, cogon).

All Chavacano words, regardless of origin, used to be written according to the Spanish orthography (kita = quita, kame = came). Furthermore, some letters were orthographically interchanged because they represented the same phonetic values. (gente = jente, cerveza = serbesa)

It is uncommon in modern Chavacano writings to include the acute accent and the trema in writing except in linguistic or highly formalized texts. Also, the letters ñ and ll are sometimes replaced by ny and ly in informal texts.

The use of inverted punctuations (¡! and ¿?) as well as the accent marks, diaeresis, and circumflex have become obsolete even in standard texts among modern dialects.

Alphabet

The Chavacano alphabet has 30 letters, including <ch>, <ll>, <ñ> and <rr>:

a, b, c, ch, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, ll, m, n, ñ, o, p, q, r, rr, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z

Letters and letter names

| A a | a /a/ | J j | jota /ˈxota/ | R r | ere /ˈeɾe/ |

| B b | be /be/ |

K k | ka /ka/ | Rr rr | erre /ˈerre/ |

| C c | ce /se/ | L l | ele /ˈele/ | S s | ese /ˈese/ |

| Ch ch | che /tʃe/ | Ll ll | elle /ˈeʎe/ | T t | te /te/ |

| D d | de /de/ | M m | eme /ˈeme/ | U u | u /u/ |

| E e | e /e/ | N n | ene /ene/ | V v | uve /ˈube/ |

| F f | efe /ˈefe/ | Ñ ñ | eñe /ˈeɲe/ | W w | doble u /ˈuve doble/ |

| G g | ge /xe/ | O o | o /o/ | X x | equis /ˈekis/ |

| H h | hache /ˈatʃe/ | P p | pe /pe/ | Y y | ye /ɟʝe/ |

| I i | i /i/ |

Q q | cu /ku/ | Z z | zeta /ˈseta/ zeda /ˈseda/ |

Other letter combinations include rr (erre), which is pronounced /xr/ or /rr/, and ng, which is pronounced /ŋɡ/. Another combination was ñg, which was pronounced /ŋ/ but is now obsolete and is only written as ng.

Some sounds are not represented in the Chavacano written language. These sounds are mostly in words of Philippine and foreign origin. Furthermore, the pronunciation of some words of Spanish origin have become distorted or Philippinized in modern Chavacano. Some vowels have become allophonized ('e' and 'o' becomes 'i' and 'u' in some words) and some consonants have changed their pronunciation. (i.e. escoger became iscují in informal speech; tiene /tʃɛnɛ/; Dios /dʒɔs/; Castilla became /kastilla/ instead of /kastiʎa/).

Glottal stops, as in Filipino languages, are not also indicated (â, ê, î, ô, û). These sounds are mainly found in words of Philippine origin and are only indicated in dictionaries (i.e. jendê = not; olê = again) and when they are, the circumflex accent is used.

Other pronunciation changes in some words of Spanish origin include:

- f ~ /p/

- j, g (before 'e' and 'i') ~ /h/ (in common with dialects of Caribbean and other areas of Latin America and southern Spain)

- ch ~ /ts/

- rr ~ /xr/

- di, de ~ /dʒ/ (when followed or preceded by other vowels: Dios ~ /jos/ ; dejalo ~ /jalo/)

- ti, te ~ /tʃ/ (when followed or preceded by other vowels: tierra ~ /chehra/; tiene ~ /chene/)

- ci, si ~ /ʃ/ (when followed or preceded by other vowels: conciencia ~ /konshensha/)

[b, d, g] between vowels which are fricative allophones are pronounced as they are in Chavacano.

Other sounds

- -h /h/ (glottal fricative in the final position); sometimes not written

- -g /k/; sometimes written as just -k

- -d /t/; sometimes written as just -t

- -kh [x]; only in loanwords of Arabic origin, mostly Islamic terms

Sounds from English

- “v” pronounced as English “v” (like: vase) (vi)

- “z” pronounced as English “z” (like: zebra) (zi)

- “x” pronounced as English “x” (like: X-ray) (ex/eks)

- “h” like: house (/eitsh/); sometimes written as 'j'

Diphthongs

| Letters | Pronunciation | Example | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|

| ae | aye | caé | fall, to fall |

| ai | ay | caido | fallen, fell |

| ao | aow | cuidao | take care, cared |

| ea | eya | patéa | kick, to kick |

| ei | eyi | reí | laugh |

| eo | eyo | vídeo | video |

| ia | ya | advertencia | warning, notice |

| ie | ye | cien(to) | one hundred, hundred |

| io | yo | canción | song |

| iu | yu | saciút | to move the hips a little |

| uo | ow | institutuo | institute |

| qu | ke | qué, que | what, that, than |

| gu | strong gi | guía | to guide, guide |

| ua | wa | agua | water |

| ue | we | cuento | story |

| ui | wi | cuidá | care, to take care |

| oi | oye | oí | hear, to hear |

Grammar

Simple sentence structure (verb–subject–object word order)

Chavacano is a language with the verb–subject–object sentence order. This is because it follows the Hiligaynon or Tagalog grammatical structures. However, the subject–verb–object order does exist in Chavacano but only for emphasis purposes (see below). New generations have been slowly and vigorously using the S-V-O pattern mainly because of the influence of the English language. These recent practices have been most prevalent and evident in the mass media particularly among Chavacano newswriters who translate news leads from English or Tagalog to Chavacano where the "who" is emphasized more than the "what". Because the mass media represent "legitimacy", it is understood by Chavacano speakers (particularly Zamboangueños) that the S-V-O sentence structure used by Chavacano journalists is standardized.

Declarative affirmative sentences in the simple present, past, and future tenses

Chavacano generally follows the simple verb–subject–object or verb–object–subject sentence structure typical of Hiligaynon or Tagalog in declarative affirmative sentences:

- Ta comprá (verb) el maga/mana negociante (subject) con el tierra (object).

- Ta comprá (verb) tierra (object) el maga/mana negociante (subject).

- Hiligaynon: Nagabakal (verb) ang mga manogbaligya (subject) sang duta (object).

- Hiligaynon: Nagabakal (verb) sang duta (object) ang mga manogbaligya (subject).

- Tagalog: Bumibili (verb) ang mga negosyante (subject) ng lupa (object).

- Tagalog: Bumibili (verb) ng lupa (object) ang mga negosyante (subject).

- (‘The businessmen are buying land.’)

The subject always appears after the verb, and in cases where pronominal subjects (such as personal pronouns) are used in sentences, they will never occur before the verb:

- Ya andá yo na iglesia enantes.

- (‘I went to church a while ago.’)

Declarative negative sentences in the simple present, past, and future tenses

When the predicate of the sentence is negated, Chavacano uses the words jendeh (from Tagalog ’hindi’ or Hiligaynon 'indi' which means ’no’; the Cebuano uses 'dili', which shows its remoteness from Chavacano as compared to Hiligaynon) to negate the verb in the present tense, no hay (which literally means ’none’) to negate the verb that was supposed to happen in the past, and jendeh or nunca (which means ’no’ or ’never’) to negate the verb that will not or will never happen in the future respectively. This manner of negating the predicate always happens in the verb–subject–object or verb–object–subject sentence structure:

Present Tense

- Jendeh ta comprá (verb) el maga/mana negociante (subject) con el tierra (object).

- Jendeh ta comprá (verb) tierra (object) el maga/mana negociante (subject).

- (Eng: The businessmen are not buying land. Span: Los hombres de negocio no están comprando terreno)

Past Tense

- No hay comprá (verb) el maga/mana negociante (subject) con el tierra (object).

- No hay comprá (verb) tierra (object) el maga/mana negociante (subject).

- (Eng: The businessmen did not buy land. Span: Los hombres de negocio no compraron terreno)

Future Tense

- Jendeh ay comprá (verb) el maga/mana negociante (subject) con el tierra (object).

- Jendeh ay comprá (verb) tierra (object) el maga/mana negociante (subject).

- (Eng: The businessmen will not buy land. Span: Los hombres de negocio no comprarán terreno)

- Nunca ay comprá (verb) el maga/mana negociante (subject) con el tierra (object).

- Nunca ay comprá (verb) tierra (object) el maga/mana negociante (subject).

- (Eng: The businessmen will never buy land. Span: Los hombres de negocio nunca comprarán terreno)

The negator jendeh can appear before the subject in a subject–verb–object structure to negate the subject rather than the predicate in the present, past, and future tenses:

Present Tense

- Jendeh el maga/mana negociante (subject) ta comprá (verb) con el tierra (object) sino el maga/mana empleados.

- (Eng: It is not the businessmen who are buying land but the employees. Span: No es el hombre de negocio que están comprando terreno sino los empleados)

Past Tense

- Jendeh el maga/mana negociante (subject) ya comprá (verb) con el tierra (object) sino el maga/mana empleados.

- (Eng: It was not the businessmen who bought the land but the employees. Span: No fue el hombre de negocio que compró el terreno sino los empleados)

Future Tense

- Jendeh el maga/mana negociante (subject) ay comprá (verb) con el tierra (object) sino el maga/mana empleados.

- (Eng: It will not be the businessmen who will buy land but the employees. Span: No sería el hombre de negocio que comprará el terreno sino los empleados)

The negator nunca can appear before the subject in a subject–verb–object structure to strongly negate (or denote impossibility) the subject rather than the predicate in the future tense:

Future Tense

- Nunca el maga/mana negociante (subject) ay comprá (verb) con el tierra (object) sino el maga/mana empleados.

- (Eng: It will never be the businessmen who will buy land but the employees. Span: Nunca sería el hombre de negocio que comprará el terreno sino los empleados)

The negator no hay and nunca can also appear before the subject to negate the predicate in a subject–verb–object structure in the past and future tenses respectively. Using nunca before the subject to negate the predicate in a subject–verb–object structure denotes strong negation or impossibility for the subject to perform the action in the future:

Past Tense

- No hay el maga/mana negociante (subject) comprá (verb) con el tierra (object).

- (Eng: The businessmen did not buy land. Span: el hombre de negocio no compró terreno)

Future Tense

- Nunca el maga/mana negociante (subject) ay comprá (verb) con el tierra (object).

- (Eng: The businessmen will never buy land. Span: el hombre de negocio nunca comprará terreno)

Nouns and Articles

The Chavacano definite article el precedes a singular noun or a plural marker (for a plural noun). The indefinite article un stays constant for gender as 'una' has almost completely disappeared in Chavacano, except for some phrases like "una vez". It also stays constant for number as for singular nouns. In Chavacano, it is quite common for el and un to appear together before a singular noun, the former to denote certainty and the latter to denote number:

- el cajón (’the box’) – el maga/mana cajón(es) (’the boxes’)

- un soltero (’a bachelor’) – un soltera (’a spinster’)

- el un soltero (’the bachelor’) – el un soltera (’the spinster’)

Nouns in Chavacano are not always precedeed by articles. Without an article, a noun is a generic reference:

- Jendeh yo ta llorá lagrimas sino sangre.

- (’I do not cry tears but blood’.)

- Ta cargá yo palo.

- (’I am carrying wood’).

Proper names of persons are preceded by the definite article si or the phrase un tal functioning as an indefinite article would:

- Un bonita candidata si Maria..

- (’Maria is a beautiful candidate’.)

- un tal Juancho

- (’a certain Juancho’)

Singular nouns

Unlike in the Spanish, Chavacano nouns derived from Spanish do not follow gender rules of the Spanish original in general. In Zamboangueño, the article 'el' basically precedes every singular noun. However, this rule is not rigid (especially in Zamboangueño) because the formal vocabulary mode wherein Spanish words predominate almost always is the preferred mode especially in writing. The Spanish article 'la' for feminine singular nouns does exist in Chavacano, though it occurs rarely and mostly in the formal medium of writing, such as poems and lyrics. When accompanying a Spanish feminine noun, the 'la' as the article is more tolerated than acceptable. Among the few exceptions where the 'la' occurs is as a formal prefix when addressing the Blessed Virgin Mary, perhaps more as an emphasis of her importance in Christian devotion. But the real article is still the 'el', which makes this use of a "double article" quite unique. Thus it is common to hear the Blessed Virgin addressed in Chavacano as 'el La Virgen Maria' (the "L" of the 'la' capitalized to signify its permanent position within the noun compound). In general, though, when in doubt, the article 'el' is always safe to use. Compare:

| English singular noun | Chavacano singular noun (general and common) | Chavacano singular noun (accepted or uncommon) |

|---|---|---|

| the virgin | el virgen | la virgen (accepted) |

| the peace | el paz | la paz (accepted) |

| the sea | el mar | la mar (accepted) |

| the cat | el gato | el gato (la gata is uncommon) |

| the sun | el sol | el sol |

| the moon | el luna | el luna (la luna is uncommon) |

| the view | el vista | la vista (accepted) |

| the tragedy | el tragedia | el tragedia (la tragedia is uncommon) |

| the doctor | el doctor | el doctora (la doctora is uncommon) |

And just like Spanish, Chavacano nouns can have gender but only when referring to persons. However, they are always masculine in the sense (Spanish context) that they are generally preceded by the article 'el'. Places and things are almost always masculine. The -o is dropped in masculine nouns and -a is added to make the noun feminine:

| English singular noun | Chavacano singular noun (masculine) | Chavacano singular noun (feminine) |

|---|---|---|

| the teacher | el maestro | el maestra |

| the witch | el burujo | el buruja |

| the engineer | el engeniero | el engeniera |

| the tailor/seamstress | el sastrero | el sastrera |

| the baby | el niño | el niña |

| the priest/nun | el padre / sacerdote | el madre / monja |

| the grandson/granddaughter | el nieto | el nieta |

| the professor | el profesor | el profesora |

| the councilor | el consejal | el consejala |

Not all nouns referring to persons can become feminine nouns. In Chavacano, some names of persons are masculine (because of the preceding article 'el' in Spanish context) but do not end in -o.

- Examples: el alcalde, el capitan, el negociante, el ayudante, el chufer

All names of animals are always masculine—in Spanish context—preceded by the article 'el'.

- Examples: el gato (gata is uncommon), el puerco (puerca is uncommon), el perro (perra is uncommon)

Names of places and things can be either masculine or feminine, but they are considered masculine in the Spanish context because the article 'el' always precedes the noun:

- el cocina, el pantalón, el comida, el agua, el camino, el trapo, el ventana, el mar

Plural nouns

In Chavacano, plural nouns (whether masculine or feminine in Spanish context) are preceded by the retained singular masculine Spanish article 'el'. The Spanish articles 'los' and 'las' have almost disappeared. They have been replaced by the modifier (a plural marker) 'maga/mana' which precedes the singular form of the noun. Maga comes from the native Hiligaynon 'maga' or the Tagalog 'mga'. The formation of the Chavacano plural form of the noun (el + maga/mana + singular noun form) applies whether in common, familiar or formal mode.

There are some Chavacano speakers (especially older Caviteño or Zamboangueño speakers) who would tend to say 'mana' for 'maga'. 'Mana' is accepted and quite common, especially among older speakers, but when in doubt, the modifier 'maga' to pluralize nouns is safer to use.

| English plural noun | Chavacano plural noun (masculine) | Chavacano plural noun (feminine) |

|---|---|---|

| the teachers | el maga/mana maestro(s) | el maga/mana maestra(s) |

| the witches | el maga/mana burujo(s) | el maga/mana buruja(s) |

| the engineers | el maga/mana engeniero(s) | el maga/mana engeniera(s) |

| the tailors/seamstresses | el maga/mana sastrero(s) | el maga/mana sastrera(s) |

| the babies | el maga/mana niño(s) | el maga/mana niña(s) |

| the priests/nuns | el maga/mana padre(s) | el maga/mana madre(s) |

| the grandsons/granddaughters | el maga/mana nieto(s) | el maga/mana nieta(s) |

| the professors | el maga/mana professor(es) | el maga/mana profesora(s) |

| the councilors | el maga/mana consejal(es) | el maga/mana consejala(s) |

Again, this rule is not rigid (especially in the Zamboangueño formal mode). The articles 'los' or 'las' do exist sometimes before nouns that are pluralized in the Spanish manner, and their use is quite accepted:

- los caballeros, los dias, las noches, los chavacanos, los santos, las mañanas, las almujadas, las mesas, las plumas, las cosas

When in doubt, it is always safe to use 'el' and 'maga or mana' to pluralize singular nouns:

- el maga/mana caballero(s), el maga/mana día(s), el maga/mana noche(s), el maga/mana chavacano(s), el maga/mana santo(s), el maga/mana día(s) que viene (this is a phrase; 'el maga/mana mañana' is uncommon), el maga/mana almujada(s), el maga/mana mesa(s), el maga/mana pluma(s)

In Chavacano, it is common for some nouns to become doubled when pluralized (called Reduplication, a characteristic of the Malayo-Polynesian family of languages):

- el maga cosa-cosa (el maga cosa/s is common), el maga casa casa (el maga casa is common), el maga gente gente (el maga gente is common), el maga juego juego (el maga juego is common)

But note that in some cases, this "reduplication" signifies a difference in meaning. For example, 'el maga bata' means 'the children' but 'el maga bata-bata' means one's followers or subordinates, as is a gang or mob.

In general, the suffixes -s, -as, -os to pluralize nouns in Spanish have also almost disappeared in Chavacano. However, the formation of plural nouns with suffixes ending in -s, -as, and -os are accepted. Basically, the singular form of the noun is retained, and it becomes plural because of the preceding modifier/plural marker 'maga' or 'mana':

- el maga/mana caballeros (accepted)

- el maga/mana caballero (correct)

- el maga/mana días (accepted)

- el maga/mana día (correct)

Adding the suffix -es to some nouns is quite common and accepted. Nouns ending in -cion can be also be pluralized by adding the suffix -es:

- el maga meses, el maga mujeres, el maga mayores, el maga tentaciones, el maga contestaciones, el maga naciones, el maga organizaciones

However, it is safer to use the general rule (when in doubt) of retaining the singular form of the noun preceded by the modifier/plural marker 'maga' or 'mana':

- el maga mes, el maga mujer, el maga mayor, el maga tentación, el maga contestación, el maga nación, el maga organización

Pronouns

Chavacano pronouns are based on native (basically Hiligaynon) and Spanish sources; many of the pronouns are not used in either but may be derived in part.

In Chavacano de Zamboanga, there are three different levels of usage for certain pronouns depending on the level of familiarity between the speaker and the addressee, the status of both in family and society, or the mood of the speaker and addressee at the particular moment: common, familiar, and formal. The common forms are, particularly in the second and third person plural, derived from Cebuano while most familiar and formal forms are from Spanish. The common forms are used to address a person below or of equal social or family status or to someone is who is acquainted. The common forms are used to regard no formality or courtesy in conversation. Its use can also mean rudeness, impoliteness or offensiveness. The familiar forms are used to address someone of equal social or family status. It indicates courteousness, and is commonly used in public conversations, the broadcast media, and in education. The formal forms are used to address someone older and/or higher in social or family status. It is the form used in writing.

Additionally, Zamboangueño is the only dialect of Chavacano which distinguishes between the inclusive we (kita) – including the person spoken to (the addressee) – and the exclusive we (kame) – excluding the person spoken to (the addressee) – in the first person plural except in the formal form where nosotros is used for both.

Personal (Nominative/Subjective Case) Pronouns

Below is a table comparing the personal pronouns in three dialects of Chavacano language.

| Zamboangueño | Caviteño | Ternateño | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular | yo | yo | |

| 2nd person singular | evo[s] (common)/(informal) tú (familiar) usted (formal) |

vo bo tu usté |

vo bo usté |

| 3rd person singular | él ele |

eli | |

| 1st person plural | kamé (exclusive/common/familiar) kitá (inclusive/common/familiar) nosotros (formal) |

nisos | mijotro mihotro motro |

| 2nd person plural | kamó (common) vosotros (familiar) ustedes (formal) |

vusos busos |

buhotro bujotro ustedi tedi |

| 3rd person plural | silá (common/familiar) ellos (formal) |

ilos | lojotro lohotro lotro |

Possessive Pronouns (Chavacano de Zamboanga)

The usage modes also exist in the possessive pronouns especially in Zamboangueño. Amon, Aton, ila and inyo are obviously of Hiligaynon(Ilonggo) but not Cebuano(Bisaya) origins, and when used as pronouns, they are of either the common or familiar mode. The inclusive and exclusive characteristics peculiar to Zamboangueño appear again in the 1st person plural. Below is a table of the possessive pronouns in the Chavacano de Zamboanga:

| Zamboangueño | |

|---|---|

| 1st person singular | mi mío de mi de mío di mio |

| 2nd person singular | de vos (common) de tu (familiar) tuyo (familiar) de tuyo (familiar) di tuyo (familiar) de usted (formal) di usted (formal) |

| 3rd person singular | su suyo de su de suyo di suyo |

| 1st person plural | de amon (common/familiar) (exclusive) di amon (common/familiar) (exclusive) de aton (common/familiar) (inclusive) diaton (common/familiar) (inclusive) nuestro (formal) de/di nuestro (formal) |

| 2nd person plural | de iño (common) di iño (common) de vosotros (familiar) de ustedes (formal) di ustedes (formal) |

| 3rd person plural | de ila (common/familiar) de ellos (formal) di ellos (formal) |

Verbs

In Zamboangueño, Chavacano verbs are mostly Spanish in origin. In contrast with the other dialects, there is rarely a Zamboangueño verb that is based on or has its origin from other Philippine languages. Hence, verbs contribute much of the Spanish vocabulary in Chavacano de Zamboanga.

Generally, the simple form of the Zamboangueño verb is based upon the infinitive of the Spanish verb, minus the final /r/. For example, continuar, hablar, poner, recibir, and llevar become continuá, hablá, poné, recibí, and llevá with the accent called "acento agudo" on the final syllable.

There are some rare exceptions. Some verbs are not derived from infinitives but from words that are technically Spanish phrases or from other Spanish verbs. For example, dar (give) does not become 'da' but dale (give) (literally in Spanish, to "give it" [verb phrase]). In this case, dale has nothing to do with the Spanish infinitive dar. The Chavacano brinca (to hop) is from Spanish brincar which means the same thing.

Verb Tenses

Simple tenses

Chavacano (especially Zamboangueño) uses the words ya (from Spanish ya [already]), ta (from Spanish está [is]), and hay (from Spanish hay [there is/there are]) plus the simple form of the verb to convey the basic tenses of past, present, and future respectively:

| English Infinitive | Spanish Infinitive | Chavacano Infinitive | Past Tense | Present Tense | Future Tense |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to sing | cantar | cantá | ya cantá | ta cantá | hay cantá |

| to drink | beber | bebé | ya bebé | ta bebé | hay bebé |

| to sleep | dormir | dormí | ya dormí | ta dormí | hay dormí |

The Chabacano of Cavite uses the words ya, ta, and di plus the simple form of the verb to convey the basic tenses of past, present, and future respectively:

| English Infinitive | Spanish Infinitive | Chabacano Infinitive | Past Tense | Present Tense | Future Tense |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to sing | cantar | cantá | ya cantá | ta cantá | di cantá |

| to drink | beber | bebé | ya bebé | ta bebé | di bebé |

| to sleep | dormir | dormí | ya dormí | ta dormí | di dormí |

While the Chabacano of Ternate (Bahra) uses the words a, ta, and di plus the simple form of the verb to convey the basic tenses of past, present, and future respectively:

| English Infinitive | Spanish Infinitive | Chabacano Infinitive | Past Tense | Present Tense | Future Tense |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to sing | cantar | cantá | a cantá | ta cantá | di cantá |

| to drink | beber | bebé | a bebé | ta bebé | di bebé |

| to sleep | dormir | dormí | a dormí | ta dormí | di dormí |

Perfect constructions

In Zamboangueño, there are three ways to express that the verb is in the present perfect. First, ya can appear both before and after the main verb to express that in the present perspective, the action has already been completed somewhere in the past with the accent falling on the final ya. Second, ta and ya can appear before and after the verb respectively to express that the action was expected to happen in the past (but did not happen), is still expected to happen in the present, and actually the expectation has been met (the verb occurs in the present). And third, a verb between ta and pa means an action started in the past and still continues in the present:

| Chavacano Past Perfect | Chavacano Present Perfect | Chavacano Present Perfect | Chavacano Future Perfect |

|---|---|---|---|

| ya cantá ya. | ta cantá ya. | ta cantá pa. / ta canta ya. | hay cantá ya. |

| ya bebé ya. | ta bebé ya. | ta bebé pa. / ta Bebe ya. | hay bebé ya. |

| ya dormí ya. | ta dormí ya. | ta dormí pa. / ta dormi ya. | hay dormí ya. |

The past perfect exists in Chavacano. The words antes (before) and despues (after) can be used between two sentences in the simple past form to show which verb came first. The words antes (before) and despues (after) can also be used between a sentence in the present perfect using ya + verb + ya and another sentence in the simple past tense:

| Past Perfect (Chavacano) | Past Perfect (English) |

|---|---|

| Ya mirá kame el película antes de ya comprá con el maga chichirías. | We had watched the movie before we bought the snacks. |

| Past Perfect (Chavacano) | Past Perfect (English) |

|---|---|

| Ya mirá ya kame el película después ya comprá kame con el maga chichirías. | We had watched the movie and then we bought the snacks. |

Zamboangueño Chavacano uses a verb between "hay" and "ya" to denote the future perfect and past perfect respectively:

| Future Perfect (Chavacano) | Future Perfect (English) |

|---|---|

| Ay mirá ya kame el película si ay llegá vosotros. | We will have watched the movie when you arrive. |

Zamboangueño Chavacano also uses a verb between "ta" and "ya" to denote the present perfect:

| Present Perfect (Zamboangueño Chavacano) | Present Perfect (English) |

|---|---|

| Ta mirá ya kame con el película mientras ta 'sperá con vosotros. | We are already watching the movie while waiting for you. |

Passive and Active Voice

To form the Zamboangueño Chavacano active voice, Zamboangueños follow the pattern:

El maga soldao ya mata con el criminal The soldiers killed the criminal.

As illustrated above, active (causative) voice is formed by placing the doer el maga soldao before the verb phrase ya mata and then the object el criminal as indicated by the particle con

Traditionally, Zamboangueño does not have a passive construction of its own.[5]

Archaic Spanish words and false friends

Chabacano has preserved plenty of archaic Spanish phrases and words in its vocabulary that modern Spanish no longer uses; for example:

- "En denantes" which means 'a while ago' (Spanish: "hace un tiempo"). Take note that "En denantes" is an archaic Spanish phrase. Modern Spanish would express the phrase as "poco antes de hoy" or "hace un tiempo", but Chabacano still retains this archaic Spanish phrase and many other archaic Spanish words. This word is still being used in some areas of southern Spain.

- "Masquen"/"Masquin" means 'even (if)' or 'although'. In Spanish, "mas que" is an archaic Spanish phrase meaning 'although', nowadays replaced by the Spanish word "aunque".[6]

- In Chavacano, the Spanish language is commonly called "castellano". Chavacano speakers, especially older Zamboangueños, call the language as "castellano" implying the original notion as the language of Castille while "español" is used to mean a Spaniard or a person from Spain.

- The pronoun "vos" is alive in Chavacano. While "vos" was used in the highest form of respect before the 16th century in classical Spanish and is quite archaic nowadays in modern Spanish (much like the English "thou"), in Chavacano it is used at the common level of usage (lower than tu, which is used at the familiar level) in the same manner of Cervantes and in the same manner as in certain Latin American countries such as Argentina (informally and in contrast with usted, which is used formally). Chavacano followed the development of vos in same manner as in Latin America – (the voseo) or, incidentally, as with English "thou" vs. "you".

- "Ansina" means 'like that' or 'that way'. In modern Spanish, "así" is the evolved form of this archaic word. The word "ansina" can still be heard among the aged in Mexico.

On the other hand, some words from the language spoken in Spain have evolved or have acquired totally different meanings in Chavacano. Hence, for Castillian speakers who would encounter Chavacano speakers, some words familiar to them have become false friends. Some examples of false friends are:

- "Siguro"/"Seguro" means 'maybe'. In Spanish, "seguro" means 'sure', 'secure', or 'stable', although it could imply probability as well, as in the phrase, "Seguramente vendrá" (Probably he will come).

- "Siempre" means 'of course'. In Spanish, "siempre" means 'always'.

- "Firmi" means 'always'. In Spanish, "firme" means 'firm' or 'steady'.

See also

Codes

Footnotes

- ↑ Spanish creole: Quilis, Antonio (1996), La lengua española en Filipinas (PDF), Cervantes virtual, p. 54 and 55

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Chavacano". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Número de hispanohablantes en países y territorios donde el español no es lengua oficial Archived April 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine., Instituto Cervantes.

- 1 2 John. M. Lipski, with P. Mühlhaüsler and F. Duthin (1996). "Spanish in the Pacific". In Stephen Adolphe Wurm & Peter Mühlhäusler. Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Texts, Volume 2 (PDF). Walter de Gruyter. p. 276. ISBN 9783110134179.

- ↑ Chabacano de Zamboanga Handbook

- ↑ Brooks 1933, Vol. 16, 1st Ed.

- ↑ Ethnologue

- 1 2 SIL International

References

- Brooks, John (1 January 1933). "Más que, mas que and mas ¡qué!". Hispania. 16 (1): 23–34. doi:10.2307/332588. JSTOR 332588.

- Castillo, Edwin Gabriel Ma., S.J. "Glosario Liturgico: Liturgical Literacy in the Chavacano de Zamboanga",(Unpublished) Archdiocese of Zamboanga.

- Chambers, John, S.J. and Wee, Salvador, S.J., editor, (2003). English-Chabacano Dictionary, Ateneo de Zamboanga University Press.

- McKaughan, Howard P. (1954). "Notes on Chabacano grammar", Journal of East Asiatic Studies 3, (205–26).

- Michaelis, Susanne., editor, (2008). Roots of Creole Structures: Weighing the contribution of substrates and superstrates, Creole Language Library Volume 33. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Rubino, Carl and Michaelis, Susanne., editor, (2008). "Zamboangueño Chavacano and the Potentive Mode", Roots of Creole Structures: Weighing the contribution of substrates and superstrates, Creole Language Library Volume 33 (279–299). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Steinkrüger, Patrick O. (2007). "Notes on Ternateño (a Philippine Spanish Creole)", Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 22(2).

- SIL.org

- Zamboangueño Chavacano por Jose Genaro Ruste Yap – Aizon, Ph.D.: (http://www.evri.com/media/article;jsessionid=ud7mj8tleegi?title=Home+|+Zamboanga+ChavacanoZamboanga+Chavacano+|+by+Jose+Genaro+...&page=http://www.josegenaroyapaizon.com/&referring_uri=/location/chavacano-language-0x398c30%3Bjsessionid%3Dud7mj8tleegi&referring_title=Evri[])

External links

| Zamboangueño Chavacano edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Meta has related information at: Wikimedia Philippines/cbk-zam |

- Chavacano at DMOZ

- A Blog about the Chabacano de Zamboanga

- Chavacano Lessons with Audio

- An abridged Chavacano dictionary

- "Jesus" A two-hour religious film in RealVideo dubbed in Chavacano

- FilipinoKastila The Spanish and Chabacano situation in the Philippines

- Ben Saavedra's speech on Chabacano at the University of the Philippines (Web archive version)

- El Chabacano El Chabacano en Español

- Austronesian Elements in Philippine Creole Spanish (pdf)

- Spanish world-wide: the last century of language contacts (PDF)

- The Puzzling Case of Chabacano: Creolization, Substrate, Mixing, and Secondary Contact by Patrick O. Steinkrüger

- Confidence in Chabacano by Michael L. Forman

- Chabacano/Spanish and the Philippine Linguistic Identity by John M. Lipski

- Noun phrases in Creole languages: a multi-faceted approach by Marlyse Baptista

- http://www.zamboanga.com/history/history_chabacano_versus_related_creoles.htm

- http://www.zamboanga.com/z/index.php?title=Category:Chavacano - An interactive online chavacano dictionary.

- http://www.christusrex.org/www1/pater/JPN-chavacano.html

- http://filipinokastila.tripod.com/chaba11.html

- http://www.sil.org/asia/philippines/ical/papers/tardo-chavacano_reader_project.pdf