Chronic traumatic encephalopathy

| Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy | |

|---|---|

|

Image of chronic traumatic encephalopathy | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Neurology, sports medicine |

| eMedicine | sports/ |

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a progressive degenerative disease found in people who have had a severe blow or repeated blows to the head. The disease was previously called dementia pugilistica (DP), i.e. "punch-drunk," as it was initially found in those with a history of boxing. CTE has been most commonly found in professional athletes participating in American football, rugby, ice hockey, boxing, professional wrestling, stunt performing, bull riding, rodeo, and other contact sports who have experienced repeated concussions or other brain trauma. Its presence in domestic violence is also being investigated. It can affect high school athletes, especially American football players, following few years of activity.[1] It is a form of tauopathy.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of CTE generally begin 8–10 years after experiencing repetitive mild traumatic brain injury.[2] First stage symptoms include deterioration in attention as well as disorientation, dizziness, and headaches. Further disabilities appear with progressive deterioration, including memory loss, social instability, erratic behavior, and poor judgment. Third and fourth stages include progressive dementia, slowing of muscular movements, hypomimia, impeded speech, tremors, vertigo, deafness, and suicidality. Additional symptoms include dysarthria, dysphagia, and ocular abnormalities - such as ptosis.[3]

Currently, CTE can only be definitively diagnosed by direct tissue examination, including full autopsies and immunohistochemical brain analyses.[4]

The neuropathological appearance of CTE is distinguished from other tauopathies, such as Alzheimer's disease. The four clinical stages of observable CTE disability have been correlated with tau pathology in brain tissue, ranging in severity from focal perivascular epicentres of neurofibrillary tangles in the frontal neocortex to severe tauopathy affecting widespread brain regions.[5]

Pathology

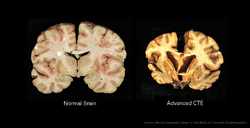

The primary physical manifestations of CTE include a reduction in brain weight, associated with atrophy of the frontal and temporal cortices and medial temporal lobe. The lateral ventricles and the third ventricle are often enlarged, with rare instances of dilation of the fourth ventricle.[6] Other physical manifestations of CTE include anterior cavum septi pellucidi and posterior fenestrations, pallor of the substantia nigra and locus ceruleus, and atrophy of the olfactory bulbs, thalamus, mammillary bodies, brainstem and cerebellum.[7] As CTE progresses, there may be marked atrophy of the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and amygdala.[2]

On a microscopic scale the pathology includes neuronal loss, tau deposition, TAR DNA-binding Protein 43 (TDP 43)[5] beta-amyloid deposition, white matter changes, and other abnormalities. The tau deposition occurs as dense neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), neurites, and glial tangles, which are made up of astrocytes and other glial cells[6] Beta-amyloid deposition is a relatively uncommon feature of CTE.

A small group of individuals with CTE have chronic traumatic encephalomyopathy (CTEM), characterized by motor neuron disease symptoms and mimics Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Progressive muscle weakness and balance and gait problems seem to be early signs of CTEM.[6]

Exosome vesicles created by the brain are potential biomarkers of TBI, including chronic traumatic encephalopathy.[8]

Diagnosis

The lack of in-vivo techniques to show distinct biomarkers for CTE is the reason CTE cannot currently be diagnosed during lifetime. The only known diagnosis for CTE occurs by studying the brain tissue after death. Concussions are non-structural injuries and do not result in brain bleeding, which is why most concussions cannot be seen on routine neuroimaging tests such as CT or MRI.[9] Acute concussion symptoms (those that occur shortly after an injury) should not be confused with CTE. Differentiating between prolonged post-concussion syndrome (PCS, where symptoms begin shortly after a concussion and last for weeks, months, and sometimes even years) and CTE symptoms can be difficult. Research studies are currently examining whether neuroimaging can detect subtle changes in axonal integrity and structural lesions that can occur in CTE.[2] Recently, more progress in in-vivo diagnostic techniques for CTE has been made, using DTI, fMRI, MRI, and MRS imaging; however, more research needs to be done before any such techniques can be validated.[6]

PET tracers that bind specifically to tau protein are desired to aid diagnosis of CTE in living individuals. One candidate is the tracer [18F]FDDNP, which is retained in the brain in individuals with a number of dementing disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, Down syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy, familial frontotemporal dementia, and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.[10] In a small study of 5 retired NFL players with cognitive and mood symptoms, the PET scans revealed accumulation of the tracer in their brains.[11] However, [18F]FDDNP, binds not only to tau but to beta-amyloid and other proteins as well. Moreover, the sites in the brain where the tracer was retained were not consistent with the known neuropathology of CTE.[12] A more promising candidate is the tracer [18F]-T807, which binds only to tau. It is being tested in several clinical trials.[12]

A putative biomarker for CTE is the presence in serum of autoantibodies against the brain. The autoantibodies were detected in football players who experienced a large number of head hits but no concussions, suggesting that even sub-concussive episodes may be damaging to the brain. The autoantibodies may enter the brain by means of a disrupted blood-brain barrier, and attack neuronal cells which are normally protected from an immune onslaught.[13] Given the large numbers of neurons present in the brain, and considering the poor penetration of antibodies across a normal blood-brain barrier, there is an extended period of time between the initial events (head hits) and the development of any signs or symptoms. Nevertheless, autoimmune changes in blood of players may consist the earliest measurable event predicting CTE.[14]

Robert A. Stern, one of the scientists at the Boston University CTE Center,[15] said in 2015 that "he expected a test to be developed within a decade that will be able to diagnose C.T.E. in living people".[16]

Prevention

Investigators have demonstrated that immobilizing the head during a blast exposure prevented the learning and memory deficits associated with CTE that occurred when the head was not immobilized. This research represents the first case series of postmortem brains from U.S. military personnel who were exposed to a blast and/or a concussive injury.[17]

Epidemiology

Professional level athletes are the largest demographic to suffer from CTE due to frequent concussions from play in contact-sport.[18] These contact-sports include American football,cheerleading, ice hockey, rugby,[19] boxing, soccer (by "heading" especially),[19] and wrestling.[20] Other individuals that have been diagnosed with CTE were involved in military service, had a previous history of chronic seizures, victims of domestic abuse, and or were involved in activities resulting in repetitive head collisions.[21]

History

CTE was first recognized as affecting individuals who took considerable blows to the head, but was believed to be confined to boxers and not other athletes. As evidence pertaining to the clinical and neuropathological consequences of repeated mild head trauma grew, it became clear that this pattern of neurodegeneration was not restricted to boxers, and the term chronic traumatic encephalopathy became most widely used.[22][23] In the early 2000s neuropathologist Dr. Bennet Omalu worked on the case of American football player Mike Webster, who had died following unusual and unexplained behaviour. In 2005 Omalu, along with colleagues in the Department of Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh, published his findings in the journal Neurosurgery in a paper which he titled "Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player." This was followed by a paper on a second case in 2006 describing similar pathology.

In 2008, the Sports Legacy Institute joined with the Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) to form the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy (CSTE).[24] Brain Injury Research Institute (BIRI) also studies the impact of concussions.[25][26]

American football

Dr. Bennet Omalu, a forensic pathologist and neuropathologist in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, found CTE in the brains of Mike Webster, Terry Long, Andre Waters, Justin Strzelczyk, and Tom McHale.[26] Omalu, in 2012 a medical examiner, then associate adjunct professor in California, was a co-founder of the Brain Injury Research Institute [26] and reportedly in 2012 participated in the autopsy of Junior Seau.[25] Omalu's participation was halted during the autopsy after Junior Seau's son revoked previously provided oral permission after he received telephone calls from NFL management denouncing Omalu's professional ethics, qualifications, and motivation.[27]

Between 2008 and 2010, the bodies of twelve former professional American football players were diagnosed with CTE postmortem by Dr. Ann McKee.[28]

On December 1, 2012, Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Jovan Belcher killed his girlfriend and drove to Arrowhead Stadium and killed himself in front of then GM Scott Pioli and then head coach Romeo Crennel. A year later, a family lawyer filed a wrongful death lawsuit, on behalf of Belcher's minor daughter, against the Chiefs alleging the team deliberately ignored warning signs of CTE, possibly leading to his suicide. The lawyer also hired a medical examiner to examine Belcher's brain for signs of CTE. On September 29, 2014, it was confirmed that he suffered from CTE.[29]

As of November 2016, 90 of 94 former National Football League (NFL) players were diagnosed post-mortem with CTE by Dr. McKee.[30] Former Detroit Lions lineman and eight-time Pro Bowler Lou Creekmur,[31] former Houston Oilers and Miami Dolphins linebacker John Grimsley,[32] former Tampa Bay Buccaneers guard Tom McHale,[33] former Cincinnati Bengals wide receiver Chris Henry,[34] former Chicago Bears safety Dave Duerson,[35] and former New England Patriots and Philadelphia Eagles running back Kevin Turner [36] have all been diagnosed post-mortem with CTE. Other football players diagnosed with CTE include former Buffalo Bills star running back Cookie Gilchrist[37] and Wally Hilgenberg.[38]

An autopsy conducted by Dr. McKee in 2010 on the brain of Owen Thomas, a 21-year-old junior lineman at the University of Pennsylvania who committed suicide, showed early stages of CTE, making him the second youngest person to be diagnosed with the condition. Thomas was the second amateur football player diagnosed with CTE, after Mike Borich, who died at 42, was also diagnosed by Dr. McKee.[39] The doctors who performed the autopsy indicated that they found no causal connection between the nascent CTE and Thomas's suicide. There were no records of Thomas missing any playing time due to concussion, but as a player who played hard and "loved to hit people", Thomas may have played through concussions and received thousands of subconcussive impacts on the brain.[40]

In October 2010, 17-year-old Nathan Stiles died hours after his high school homecoming football game, where he took a hit that would be the final straw in a series of subconcussive and concussive blows to the head for the highschooler. The CSTE diagnosed him with CTE, making him the youngest reported CTE case to date.[41]

In July, 2011, Colt tight end John Mackey died after several years of deepening symptoms of frontotemporal dementia. BUSM was reported to be planning to examine his brain for signs of CTE.[42] The CSTE found CTE in his brain post-mortem.[43]

In 2012, retired NFL player Junior Seau committed suicide with a gunshot wound to the chest.[44] There was speculation that he suffered brain damage due to CTE.[25][45][46][47][48] Seau's family donated his brain tissue to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.[49] On January 10, 2013, the brain pathology report was revealed and Seau did have evidence of CTE.[50]

On July 27, 2012, an autopsy report concluded that the former Atlanta Falcons safety Ray Easterling, who committed suicide in April 2012, had CTE.[51][52]

The NFL has taken measures to help prevent CTE. As of July 2011, the NFL has changed its return-to-play rules. The number of contact practices has been reduced, based on the recent collective bargaining agreement.[53]

In 2012, some four thousand former NFL players "joined civil lawsuits against the League, seeking damages over the League's failure to protect players from concussions, according to Judy Battista of the [New York] Times".[54]

On August 30, 2013, the NFL reached a $765 million settlement with the former NFL players over the head injuries.[55] The settlement created a $675 million compensation fund from which former NFL players can collect depending on the extent of their conditions. Severe conditions such as Lou Gehrig's disease and postmortem diagnosed chronic traumatic encephalopathy would be entitled to payouts as high as $5 million.[55] From the remainder of the settlement, $75 million will be used for medical exams, and $10 million will be used for research and education.[55] However, in January, 2014, U.S. District Judge Anita B. Brody refused to accept the agreed settlement because "the money wouldn't adequately compensate the nearly 20,000 men not named in the suit".[56] In the settlement Brody did accept, she argued that people "cannot be compensated for C.T.E. in life because no diagnostic or clinical profile of C.T.E. exists, and the symptoms of the disease, if any, are unknown".[16]

On April 22, 2015 a final settlement was reached between players and the NFL in the case adjudicated by Judge Brody. Terms include payments to be made by the NFL for $75 million for "baseline medical exams" for retired players, $10 million for research and education, as well an uncapped amount for retirees "who can demonstrate that they suffer from one of several brain conditions covered by the agreement", with total payments expected to exceed $1 billion over 65 years.[57]

In September 2015, researchers with the Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University announced that they had identified CTE in 96 percent of NFL players that they had examined and in 79 percent of all football players.[58]

On January 26, 2016, an autopsy report released by the family of former New York Giants safety Tyler Sash confirmed that Sash was suffering from CTE at the time of his death at age 27 in September 2015.[59]

On February 4, 2016, an autopsy report from Massachusetts confirmed discovered high Stage 3 chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in Ken Stabler's brain after his death.[60]

On March 14, 2016, the top NFL official, Jeff Miller, publicly admitted that there is a link between football and CTE at the roundtable discussion on concussions.[61]

Early retirements

In the 2015 off-season, a number of NFL players retired early with concussion- and other health-risk as expressed or possible motive. The youngest, in March, Chris Borland, 24, would have been entering his second year in the league after a third-round draft out of University of Wisconsin and a "stellar" rookie season with the San Francisco 49ers.[62] Explaining his decision to ESPN, Borland said "I just honestly want to do what's best for my health. ... From what I've researched and what I've experienced, I don't think it's worth the risk."[63]

Patrick Willis, a seven-time All-Pro linebacker also with the 49ers, [had previously] announced that he was retiring rather than risk further injury. However Willis' decision to retire has nothing to do with CTE, but rather as he explained: "You’ve seen me break my hand on Sunday, have surgery on Monday and play on Thursday with a cast on," Willis said. "But there's something about these feet. And those are what made me who I am. They had you all saying, ‘Wow, where’d he come from?’ "I know I no longer have it in these feet to go out there and give you guys that kind of ‘Wow.’"[64] Cornerback Cortland Finnegan of the St. Louis Rams, quarterback Jake Locker of the Tennessee Titans and linebacker Jason Worilds of the Pittsburgh Steelers have all retired this off-season as well. ... Worilds, who was paid $9.75 million by the Steelers in 2014, was expected to sign a big contract with another team as a free agent. [Borland] won Rookie of the Week honors twice and was Defensive Rookie of the Month in November [in 2014]. He earned the league-minimum $420,000 and a bonus of $154,000, according to Overthecap.com.[62]

ESPN noted that four of the retirees—Borland, Willis, Locker and Worilds—were under 30 years of age and that Borland had replaced Willis during the season due to a Willis toe injury and had been expected to replace him in the coming year. It also recounted Borland's course of decision from a possible concussion he "played through" in training camp as he was trying to make the team to the post-season decision. He said in making his decision he'd "read about Mike Webster and Dave Duerson and Ray Easterling"—two of them suicides, all, per ESPN, "diagnosed with the devastating brain disease Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, after their deaths"—and he had talked to "prominent concussion researchers and former players" after the season.[63]

In the 2016 off-season, A.J. Tarpley,[65] Husain Abdullah,[66] and Eugene Monroe[67] all announced early retirements from the NFL, each citing concern over sustaining further head trauma as the main factor in their decision.

Ice hockey

Athletes from other sports have also been identified as having CTE, such as hockey player Bob Probert.[68] Neuropathologists at Boston University diagnosed Reg Fleming as the first hockey player known to have the disease. This discovery was announced in December 2009, six months after Fleming's death.[69]

Rick Martin, best known for being part of the Buffalo Sabres' French Connection, was diagnosed with CTE after his brain was posthumously analyzed.[70] Martin was the first documented case of an ice hockey player not known as an enforcer to have developed CTE; Martin was believed to have developed the disease primarily as a result of a severe concussion he suffered in 1977 while not wearing a helmet. The disease was low-grade and asymptomatic in his case, not affecting his cognitive functions. He died of a heart attack in March 2011 at the age of 59.[71]

Also within a few months in 2011, the deaths of three hockey "enforcers"—Derek Boogaard from a combination of too many painkillers and alcohol, Rick Rypien, an apparent suicide, and Wade Belak, who, like Rypien, had reportedly suffered from depression; and all with a record of fighting, blows to the head and concussions—led to more concerns about CTE. Boogaard's brain was examined by BUSM, which in October 2011 determined the presence of CTE.[72] One National Hockey League player known in part for leading "the thump parade", former Boston Bruin and current Florida Panthers right winger Shawn Thornton mulled over the "tragic coincidence" of the three recent league deaths and agreed that their deaths were due to the same cause, yet still defended the role of fighting on the rink.[73]

In 2016, Stephen Peat, now 36 and formerly an enforcer for the Washington Capitals during his professional career, was reported to be suffering severe symptoms of CTE. His father Walter was reported to worry that his son would join the "dead before turning 50 ... since 2010" list of enforcers including Boogaard, Rypien, Belak, Steve Montador and Todd Ewen.[74]

Professional wrestling

In 2007, neuropathologists from the Sports Legacy Institute (an organization co-founded by Christopher Nowinski, himself a former professional wrestler) examined the brain of Chris Benoit, a professional wrestler with the WWE, who had apparently killed his wife and son before committing suicide. The suicide and double murder were originally attributed to anabolic steroid abuse, but a brain biopsy confirmed pathognomonic CTE tissue changes: large aggregations of tau protein as manifested by neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads, which cause neurodegeneration.[75][76]

In 2009, Bennet Omalu discovered CTE in recently retired wrestler Andrew "Test" Martin, who died at age 33 from an accidental medicine overdose.[77]

On February 9, 2016, Daniel Bryan was forced to retire early due to suffering from signs of CTE and post-concussion seizures.[78]

Mixed martial arts

It is believed that former MMA Fighters Gary Goodridge and James Leahy suffer from CTE, as a result of repeated head trauma from their fighting careers. Delayed onset is becoming increasingly common as with Leahy, whose symptoms developed many years post any sporting activity.[79]

In October 2016, Dr. Bennet Omalu announced that CTE had been detected in the brain of Jordan Parsons, an MMA fighter who had been killed the previous May by a drunk driver.[80]

Association football

In 2012, Patrick Grange a semi-professional footballer, was diagnosed in an autopsy with Stage 2 CTE with motor neuron disease. "The fact that Patrick Grange was a prolific header is important", Christopher Nowinski, co-founder of the Sports Legacy Institute, said in an e-mail. "We need a larger discussion around at what age we introduce headers, and how we set limits to exposure once it is introduced."[81] Grange played football at high school; college at Illinois-Chicago and New Mexico; in the Premier Development League; for Albuquerque Asylum and Chicago Fire Premier. He died of ALS at age 29 in 2012 with a posthumous diagnosis of CTE.[82]

In 2014, Brazilian footballer Bellini was posthumously diagnosed with CTE. Bellini, along with Pelé, led Brazil to FIFA World Cup victories in 1958 and 1962.[83]

West Bromwich Albion forward Jeff Astle died in January 2002 following five years of deteriorating mental health. Originally diagnosed as Alzheimer's, Astles condition was later rediagnosed as CTE. In 2014 following 12 years of campaigning from his family and fans at his former club West Bromwich Albion, Jeff Astle officially became the first British footballer listed to have died as a result of heading a football. The campaign was known as the 'Justice for Jeff' campaign, it's awareness raised by West Bromwich Albion supporters minutes of applause on the 9th minute of every match (his squad number). Astle was particularly noted for his powerful heading off the ball, it is believed that this, combined with the weight of the old fashioned leather footballs contributed to his CTE.

Rugby

Researchers found Australian rugby union player Barry "Tizza" Taylor died in 2013 of complications of severe CTE with dementia at age 77. Taylor played for 19 years in amateur and senior leagues before becoming a coach.[81]

In 2013, Dr Willie Stewart, Consultant Neuropathologist at the Institute of Neurological Sciences at the Southern General Hospital in Glasgow, identified CTE in the brain of a former amateur rugby player in his 50s which is believed to be the first confirmed case of early onset dementia caused by CTE in a rugby player.[84]

Australian rules football

Australian rules football player Greg Williams is thought to have CTE as a result of concussions over a 250-game career.[85]

In March 2016 Justin Clarke of the Australian Football League (AFL) team the Brisbane Lions was forced to retire at just 22 years of age due to a serious concussion sustained during off-season training two months earlier.[86] He was the fifth AFL player in the previous ten months to retire with concussion related injuries, with Sam Blease (25 yo, Melbourne and Geelong), Leigh Adams (27 yo, North Melbourne), Matt Maguire (32 yo, Brisbane and St Kilda), and Brent Reilly (32 yo, Adelaide) all having retired since May 2015. All the retirements were linked to a crackdown on head injuries by the AFL and fears of CTE associated with local and international sportspeople, especially American footballers.[87]

Major League Baseball

In 2012, the brain tissue of Ryan Freel was tested after his death. It was found that he had Stage 2 CTE. Freel was the first Major League Baseball player to be diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy.[88]

Extreme sports

In 2016, BMX biker and extreme sport icon Dave Mirra was diagnosed post-mortem with CTE. He had committed suicide by gunshot on February 4, 2016, and his brain was examined by Dr. Lili-Naz Hazrati of the University of Toronto, who confirmed the diagnosis.[89]

Society and culture

Notable cases

Professional wrestling

In 2007, neuropathologists from the Sports Legacy Institute (an organization co-founded by Christopher Nowinski, himself a former professional wrestler) examined the brain of Chris Benoit, a professional wrestler with the WWE, who had apparently killed his wife and son before committing suicide. The suicide and double murder were originally attributed to anabolic steroid abuse, but a brain biopsy confirmed pathognomonic CTE tissue changes: large aggregations of tau protein as manifested by neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads, which cause neurodegeneration.[75][76]

In 2009, Bennet Omalu discovered CTE in recently retired professional wrestler Andrew "Test" Martin, who died at age 33 from an accidental medicine overdose.[77]

In February 2016, Daniel Bryan was forced to retire early due to neck issues and suffering from signs of CTE and post-concussion seizures.[78]

In July 2016, 53 professional wrestlers filed a suit against WWE, looking to hold the organization accountable for their "long-term neurological injuries" due to concussion and CTE.[90]

Football

While the following list is incomplete, the list of just NFL players tops the 4500 who reached a legal settlement with the National Football League (NFL) in 2013 and appears on a separate page for length:

Baseball

Action Sports

Popular culture

On October 8, 2013, PBS aired an episode of its Frontline documentary television series concerning CTE and the NFL.[96] The episode was re-aired in December 2015 with additional updated information.

Research

In 2005 forensic pathologist Bennet Omalu, along with colleagues in the Department of Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh, published a paper, "Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player", in the journal Neurosurgery, based on analysis of the brain of deceased former NFL center Mike Webster. This was then followed by a paper on a second case in 2006 describing similar pathology, based on findings in the brain of former NFL player Terry Long.

In 2008, the CSTE at Boston University at the BU School of Medicine started the CSTE brain bank at the Bedford VA Hospital to analyze the effects of CTE and other neurodegenerative diseases on the brain and spinal cord of athletes, military veterans, and civilians[5] To date the CSTE Brain Bank is the largest CTE tissue repository in the world.[6] On December 21, 2009, the National Football League Players Association announced that it would collaborate with the CSTE at the Boston University School of Medicine to support the Center's study of repetitive brain trauma in athletes.[97] Additionally, in 2010 the National Football League gave the CSTE a $1 million gift with no strings attached.[98][99] In 2008, twelve living athletes (active and retired), including hockey players Pat LaFontaine and Noah Welch as well as former NFL star Ted Johnson, committed to donate their brains to CSTE after their deaths.[24][100] In 2009, NFL Pro Bowlers Matt Birk, Lofa Tatupu, and Sean Morey pledged to donate their brains to the CSTE.[101] In 2010, 20 more NFL players and former players pledged to join the CSTE Brain Donation Registry, including Chicago Bears linebacker Hunter Hillenmeyer, Hall of Famer Mike Haynes, Pro Bowlers Zach Thomas, Kyle Turley, and Conrad Dobler, Super Bowl Champion Don Hasselbeck and former pro players Lew Carpenter, and Todd Hendricks. In 2010, Professional Wrestlers Mick Foley, Booker T and Matt Morgan also agreed to donate their brains upon their deaths. Also in 2010, MLS player Taylor Twellman, who had to retire from the New England Revolution because of post-concussion symptoms, agreed to donate his brain upon his death. As of 2010, the CSTE Brain Donation Registry consists of over 250 current and former athletes.[102] In 2011, former North Queensland Cowboys player Shaun Valentine became the first rugby player to agree to donate his brain upon his death, in response to recent concerns about the effects of concussions on Rugby League players, who do not use helmets. Also in 2011, boxer Micky Ward, whose career inspired the film The Fighter, agreed to donate his brain upon his death.

In related research, the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes, which is part of the Department of Exercise and Sport Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is conducting research funded by National Football League Charities to "study former football players, a population with a high prevalence of exposure to prior Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI) and sub-concussive impacts, in order to investigate the association between increased football exposure and recurrent MTBI and neurodegenerative disorders such as cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease (AD)".[103]

In February 2011, Dave Duerson committed suicide,[48] leaving text messages to loved ones asking that his brain be donated to research for CTE.[104] The family got in touch with representatives of the Boston University center studying the condition, said Robert Stern, the co-director of the research group. Stern said Duerson's was the first time he was aware of that such a request had been left by a suicide potentially linked to CTE.[105] Stern and his colleagues found high levels of the protein tau in Duerson's brain. These elevated levels, which were abnormally clumped and pooled along the brain sulci,[5] are indicative of CTE.[35]

In July 2010, NHL enforcer Bob Probert died of heart failure. Before his death, he asked his wife to donate his brain to CTE research because it was noticed that Probert experienced a mental decline in his 40s. In March 2011, researchers at Boston University concluded that Probert had CTE upon analysis of the brain tissue he donated. He is the second NHL player from the program at the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy to be diagnosed with CTE postmortem.[106]

BUSM has also found indications of links between Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and CTE in athletes who have participated in contact sports. Tissue for the study was donated by twelve athletes and their families to the CSTE Brain Bank at the Bedford, Massachusetts VA Medical Center.[107]

In 2013, President Barack Obama announced the creation of the Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium or CENC, a federally funded research project devised to address the long-term effects of mild traumatic brain injury in military service personnel (SMs) and Veterans.[108][109][110] The CENC is a multi-center collaboration linking premiere basic science, translational, and clinical neuroscience researchers from the DoD, VA, academic universities, and private research institutes to effectively address the scientific, diagnostic, and therapeutic ramifications of mild TBI and its long-term effects.[111][112][113][114][115] Nearly 20% of the more than 2.5 million U.S. Service Members (SMs) deployed since 2003 to Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) have sustained at least one traumatic brain injury (TBI), predominantly mild TBI (mTBI),[116][117] and almost 8% of all OEF/OIF Veterans demonstrate persistent post-TBI symptoms more than six months post-injury.[118][119] Unlike those head injuries incurred in most sporting events, recent military head injuries are most often the result of blast wave exposure [citation required]. After a competitive application process, a consortium led by Virginia Commonwealth University was awarded funding.[111][112][113][114][120][121] The project principal investigator for the CENC is David Cifu, Chairman and Herman J. Flax professor[122] of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in Richmond, Virginia, with co-principal investigators Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, Professor of Neurology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences,[114] and Rick L. Williams, statistician at RTI International.

Like all scientific theories, the hypothesis that repeated concussion or subconcussive impacts cause CTE cannot be definitively proven. To date no scientific evidence has been shown to falsify the hypothesis, while a rapidly growing body of evidence from postmortem and epidemiological studies conducted at major researcher institutions and the National Football League supports it.[123]

Some researchers have argued that prospective longitudinal studies employing the scientific method are needed to provide adequate confirmation for the hypothesis that repeated concussion or subconcussive impacts cause CTE. [124]

As of September 2015, the CSTE had diagnosed CTE in 96% of NFL players analyzed in postmortem brain studies.[125]

References

- ↑ Toporek, Bryan. "New: High School Football Can Lead to Long-Term Brain Damage, Study Says". Education Week. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE, Santini VE, Lee HS, Kubilus CA, Stern RA (2009). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury". J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 68 (7): 709–35. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503. PMC 2945234

. PMID 19535999.

. PMID 19535999. - ↑ Corsellis; et al. (1973). "The Aftermath of Boxing". Psychological Medicine. 3 (3): 270–303. doi:10.1017/S0033291700049588. PMID 4729191.

- ↑ Omalu; et al. (2010). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, suicides and parasuicides in professional American athletes: the role of the forensic pathologist". Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 31 (2): 130–2. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181ca7f35. PMID 20032774.

- 1 2 3 4 McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Stein TD, Alvarez VE, Daneshvar DH, Lee HS, Wojtowicz SM, Hall G, Baugh CM, Riley DO, Kubilus CA, Cormier KA, Jacobs MA, Martin BR, Abraham CR, Ikezu T, Reichard RR, Wolozin BL, Budson AE, Goldstein LE, Kowall NW, Cantu RC (2013). "The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy". Brain. 136 (Pt 1): 43–64. doi:10.1093/brain/aws307. PMC 3624697

. PMID 23208308.

. PMID 23208308. - 1 2 3 4 5 Baugh CM, Stamm JM, Riley DO, Gavett BE, Shenton ME, Lin A, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, McKee AC, Stern RA (2012). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: neurodegeneration following repetitive concussive and subconcussive brain trauma". Brain Imaging Behav. 6 (2): 244–254. doi:10.1007/s11682-012-9164-5. PMID 22552850.

- ↑ Jancin, Bruce (1 June 2011). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy test sought". Internal Medicine News. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C (2014). "Exosome platform for diagnosis and monitoring of traumatic brain injury". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 369 (1652): 20130503. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0503. PMC 4142024

. PMID 25135964.

. PMID 25135964. - ↑ Poirier MP (2003). "Concussions: Assessment, management, and recommendations for return to activity". Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 4 (3): 179–85. doi:10.1016/S1522-8401(03)00061-2.

- ↑ Villemagne VL, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Masters CL, Rowe CC (2015). "Tau imaging: early progress and future directions". The Lancet. Neurology. 14 (1): 114–24. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70252-2. PMID 25496902.

- ↑ Small GW, Kepe V, Siddarth P, Ercoli LM, Merrill DA, Donoghue N, Bookheimer SY, Martinez J, Omalu B, Bailes J, Barrio JR (2013). "PET scanning of brain tau in retired national football league players: preliminary findings". Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 21 (2): 138–144. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.019. PMID 23343487.

- 1 2 Montenigro PH, Corp DT, Stein TD, Cantu RC, Stern RA (2015). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: historical origins and current perspective". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 11: 309–30. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112814. PMID 25581233.

- ↑ John Mangels, Cleveland Plain Dealer, 2013/03.

- ↑ Marchi N, Bazarian JJ, Puvenna V, Janigro M, Ghosh C, Zhong J, Zhu T, Blackman E, Stewart D, Ellis J, Butler R, Janigro D (2013). "Consequences of repeated blood-brain barrier disruption in football players". PLoS ONE. 8 (3): e56805. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056805. PMC 3590196

. PMID 23483891.

. PMID 23483891. - ↑ "Robert A. Stern, Ph.D." (bio), BU CTE Center. Retrieved 2015-08-11.

- 1 2 Nocera, Joe, "N.F.L.'s Bogus Settlement for Brain-Damaged Former Players" (op-ed column), New York Times, August 11, 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-11.

- ↑ Goldstein LE, Fisher AM, Tagge CA, Zhang XL, Velisek L, Sullivan JA, Upreti C, Kracht JM, Ericsson M, Wojnarowicz MW, Goletiani CJ, Maglakelidze GM, Casey N, Moncaster JA, Minaeva O, Moir RD, Nowinski CJ, Stern RA, Cantù RC, Geiling J, Blusztajn JK, Wolozin BL, Ikezu T, Stein TD, Budson AE, Kowall NW, Chargin D, Sharon A, Saman S, Hall GF, Moss WC, Cleveland RO, Tanzi RE, Stanton PK, McKee AC (2012). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in blast-exposed military veterans and a blast neurotrauma mouse model". Sci Transl Med. 4 (134): 134ra60. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003716. PMC 3739428

. PMID 22593173.

. PMID 22593173. - ↑ Saulle M, Greenwald BD (2012). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a review" (PDF). Rehabil Res Pract. 2012: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2012/816069. PMC 3337491

. PMID 22567320.

. PMID 22567320. - 1 2 Stone, Paul (March 18, 2014). "First Soccer and Rugby Players Diagnosed With CTE". Neurologic Rehabilitation Institute at Brookhaven Hospital. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ↑ Daneshvar DH, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC, Cantu RC (2011). "The epidemiology of sport-related concussion". Clin Sports Med. 30 (1): 1–17, vii. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2010.08.006. PMC 2987636

. PMID 21074078.

. PMID 21074078. - ↑ Daneshvar DH, Riley DO, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC, Stern RA, Cantu RC (2011). "Long-term consequences: effects on normal development profile after concussion". Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 22 (4): 683–700, ix. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2011.08.009. PMC 3208826

. PMID 22050943.

. PMID 22050943. - ↑ Martland H (1928). "Punch Drunk". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 91 (15): 1103–1107. doi:10.1001/jama.1928.02700150029009.

- ↑ Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: A Potential Late Effect of Sport-Related Concussive and Subconcussive Head Trauma

- 1 2 Staff. "New pathology findings show significant brain degeneration in professional athletes with history of repetitive concussions", Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, September 25, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Seau family revisiting brain decision". ESPN.com. May 6, 2012. Archived from the original on May 6, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Our Team". Brain Injury Research Institute. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "87 Deceased NFL Players Test Positive for Brain Disease (CTE)". NeoGAF. Retrieved 2015-11-28.

- ↑ Gavett BE, Stern RA, McKee AC (2011). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a potential late effect of sport-related concussive and subconcussive head trauma". Clin Sports Med. 30 (1): 179–188, xi. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.007. PMC 2995699

. PMID 21074091.

. PMID 21074091. - ↑ "OTL: Belcher's brain had CTE signs". ESPN.com.

- ↑ "Case Studies » CTE Center | Boston University". www.bu.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ↑ Case Study: Lou Creekmur, Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. Accessed August 17, 2010.

- ↑ Case Study: John Grimsley, Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. Accessed August 17, 2010.

- ↑ Case Study: Thomas McHale, Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. Accessed August 17, 2010.

- ↑ Schwarz, Alan (June 28, 2010). "Former Bengal Henry Found to Have Had Brain Damage". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- 1 2 Deardorff, Julie (May 2, 2011). "Study: Duerson had brain damage at time of suicide". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Former NFL player Kevin Turner diagnosed with CTE".

- ↑ Gaughan, Mark (November 6, 2011). Gilchrist had severe damage to brain Archived November 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. The Buffalo News. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ↑ Gladwell, Malcolm (October 18, 2009). "Offensive Play". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Staff. "First former college football player diagnosed with CTE: Former Brigham Young University Football Coach Died at 42", Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, October 22, 2009. Accessed October 19, 2010.

- ↑ Schwarz, Alan. "Suicide Reveals Signs of a Disease Seen in N.F.L.", The New York Times, September 13, 2010. Accessed September 14, 2010.

- ↑ "Brain Bank examines athletes' hard hits". CNN.com. 27 Jan 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Cowherd, Kevin, "Mackey leaves enduring legacy on and off field", Baltimore Sun, July 07, 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ↑ "Study : new cases of CTE in players". ESPN.com. 3 Dec 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Duke, Alan; Chelsea J. Carter (3 May 2012). "Junior Seau's death classified as a suicide". CNN.com. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Duke, Alan; Chelsea J. Carter. "Doctors to examine Junior Seau's brain". CNN. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Given, Karen (May 12, 2012). "Researchers Compete For Athletes' Brains". wbur.org. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Farmer, Sam (May 3, 2012). "Family of Junior Seau will allow his brain to be studied". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012.

- 1 2 Smith, Michael David, "Boston researchers request Junior Seau's brain". NBC Sports Pro Football Talk, May 3, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ↑ Lavelle, Janet (July 12, 2012). "Seau brain tissue donated for research". U-T San Diego. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012.

- ↑ Wilner, Barry (January 10, 2013). "NFL's Junior Seau had brain disease CTE when he killed himself". The Washington Times.

- ↑ "Autopsy: Former Falcons safety Ray Easterling had brain disease associated with concussions", CBS/AP, July 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Ray Easterling autopsy found signs of brain disease CTE", New York Times, July 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Even high school practices will be tougher than NFL workouts". NFL.com. 24 July 2011.

- ↑ Coll, Steve, "Is Chaos a Friend of the N.F.L.?", The New Yorker, December 26, 2012. Citing the Times. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- 1 2 3 Connor, Tracy (30 August 2013). "NFL and players reach $765 million settlement over head injuries". U.S. News. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ "Judge scuttles NFL's $760M concussion settlement", MarketWatch citing NBC10 Philadelphia, January 14, 2014. Retrieved 2014-01-15.

- ↑ Breslow, Jason M. "NFL Concussion Settlement Wins Final Approval from Judge". pbs.org. PBS. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ↑ Breslow, Jason. "New: 87 Deceased NFL Players Test Positive for Brain Disease". Frontline. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ Pennington, Bill (January 26, 2016). "Former Giants Safety Found To Have C.T.E.". New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ↑ "Raiders great Ken Stabler had Stage 3 chronic traumatic encephalopathy". CBSSports.com. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ↑ Fainaru, Steve (March 15, 2016). "Top NFL official acknowledges, for the first time, link between football, brain disease". Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- 1 2 Belson, Ken, "49ers’ Chris Borland, a Top N.F.L. Rookie, Will Retire Because of Safety Concerns", New York Times, March 17, 2015. Cited in the article: "49ers LB Chris Borland to Retire from NFL" from the 49ers website. The 49ers post gave Borland's NFL and college stats, including: "Borland (5-11, 248) was the second of the 49ers three, third-round draft picks (77th overall) in the 2014 NFL Draft out of the University of Wisconsin. In his only season with the 49ers, Borland appeared in 14 games (eight starts) and registered a team-high 128 tackles, two interceptions, one sack and one fumble recovery. ... Borland finished his playing career at Wisconsin ranked 6th all-time in total tackles (420), 4th in tackles for loss (50) and tied for 8th in sacks (17.0). He played in 55 games (48 starts) for the Badgers and also registered 18 passes defensed, 15 forced fumbles, eight fumble recoveries and three interceptions." Retrieved 2015-03-17.

- 1 2 Fainaru-Wada, Mark, and Steve Fainaru, "SF's Borland quits over safety issues", ESPN.com, updated March 17, 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-17.

- ↑ Emerick, Tyler. "Patrick Willis Explains Decision to Retire from NFL".

- ↑ Tarpley, A.J. (April 12, 2016). "A.J. Tarpley: Why I Walked Away from Football at 23". Sports Illustrated. The MMBQ. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ Abdullah, Husain (April 18, 2016). "The Right Decision". The Players' Tribune. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ Monroe, Eugene (July 21, 2016). "Leaving the Game I Love". The Players' Tribune. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ Schwarz, Alan (2011-03-02). "Hockey Enforcer Bob Probert Paid a Price, With Brain Trauma". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ↑ Schwarz, Alan; Klein, Jeff Z. (December 18, 2009). "Brain Damage Found in Hockey Player". The New York Times.

- ↑ Klein, Jeff Z. (October 5, 2011). "Former Star Had Disease Linked to Brain Trauma". New York Times.

- ↑ Golen, Jimmy (October 5, 2011). Brain study finds damage in Rick Martin Archived October 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. Associated Press. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Derek Boogard – A Brain 'Going Bad'", New York Times, Dec 5, 2011 10:05 AM ET. Part 3 of a three-part series chronicling Boogard's life and the posthumous research on his brain. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ Shinzawa, Fluto, "Grind of the enforcer difficult to fight through", Boston Globe, September 11, 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ↑ Branch, John, "After a Life of Punches, Ex-N.H.L. Enforcer Is a Threat to Himself", New York Times, June 1, 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-01.

- 1 2 Tagami Ty (2010-10-16). "Chris Benoit's father: Murderous rampage resulted from brain damage, not steroids". Atlantic Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on 2010-10-19. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- 1 2 Sports Legacy Institute (2007-09-05). "Wrestler Chris Benoit Brain's Forensic Exam Consistent With Numerous Brain Injuries". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- 1 2 Garber, Greg (2009-12-08). "Andrew 'Test' Martin suffered from postconcussion brain damage, researchers say". ESPN. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- 1 2 "Daniel Bryan on concussions: You have a responsibility to yourself – ESPN Video". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ Fowlkes, Ben, "Gary Goodridge, former MMA fighter and kickboxer, offers cautionary tale", Sports Illustrated, March 15, 2012. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- ↑ Hohler, Bob. "First case of CTE diagnosed in MMA fighter", The Boston Globe, October 21, 2016. Accessed October 30, 2016. "He was only 25, but Jordan Parsons was a cage fighter, a professional mixed martial artist who on his best nights beat his opponents into submission. On his worst nights, Parsons was sent spiraling to the canvas by devastating blows to his head. Now, six months after he was struck and killed as a pedestrian by an alleged drunken driver, Parsons is the first fighter in the multibillion-dollar MMA industry to be publicly identified as having been diagnosed with the degenerative brain disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)."

- 1 2 "First soccer, rugby players diagnosed with CTE", edition.cnn.com, 2014/02/28.

- ↑ Branch, John, "Brain Trauma Extends to the Soccer Field", The New York Times, February 26, 2014. Accessed February 26, 2014.

- ↑ washingtonpost.com, 2014/09/23.

- ↑ BBC News "Rugby 'linked to early onset dementia'", BBC News', August 3, 2013.

- ↑ Sheehan, Paul, "Concussion a concern from elite to schools", The Sydney Morning Herald, February 27, 2013. Accessed December 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Brisbane Lions defender Justin Clarke quits AFL at 22, after training accident leaves him with serious concussion and memory issues". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ Ralph, Jon (1 April 2016). "Justin Clarke becomes the fifth player to retire because of concussion as player manager Peter Jess calls for blindside tackle ban". Herald Sun. News Corp Australia. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ "First Major League Baseball player diagnosed with CTE", edition.cnn.com, 2013/12/15.

- ↑ Kounang, Nadia (May 25, 2016). "Late BMX biker Dave Mirra had CTE". CNN. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- ↑ Machkovech, Sam (19 July 2016). "53 wrestlers file class-action civil suit against WWE over concussions, CTE". Ars Technica. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ↑ Conway, Tyler, "Autopsy of Former Ravens Quarterback Cullen Finnerty Reveals CTE", bleacherreport.com, August 8, 2013. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- ↑ Gola, Hank. "Ex-cop pens Cookie Gilchrist bio". New York Daily News. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- 1 2 "Bobby Kuntz And Jay Roberts, Former CFL Players, Test Results Show They Had Brain Disease". Huffington Post. CP. 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- ↑ Snyder, Matt. "Report: Ryan Freel was suffering from CTE at time of death". CBSSports.com. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Ley, Tom. "report: BMX Star Dave Mirra Had CTE When He Committed Suicide". deadspin.com. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑ "League of Denial: The NFL's Concussion Crisis". PBS. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ↑ Staff. "NFL Players Association to Support Brain Trauma Research at Boston University", Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy press release dated December 21, 2009. Accessed August 17, 2010.

- ↑ Support and Funding Archived July 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine., Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. Accessed August 17, 2010.

- ↑ Schwarz, Alan. "N.F.L. Donates $1 Million for Brain Studies", The New York Times, April 20, 2010. Accessed August 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Welch to donate brain for concussion study". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on 2010-10-06. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Staff. "Three active NFL Pro Bowl players to donate brains to research", Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy press release dated September 14, 2009. Accessed August 17, 2010.

- ↑ Staff. "20 more NFL stars to donate brains to research", Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy press release dated February 1, 2010. Accessed August 17, 2010.

- ↑ "A Study on the Association Between Football Exposure and Dementia in Retired Football Players". UNC College of Arts and Sciences.

- ↑ Kusinski, Peggy (2011-02-19). "Dave Duerson Committed Suicide: Medical Examiner". NBC Chicago. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ↑ Schwarz, Alan (February 20, 2011). "Before Suicide, Duerson Asked for Brain Study". The New York Times.

- ↑ Schwarz, Alan (March 2, 2011). "Hockey Brawler Paid Price, With Brain Trauma". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Researchers Discover Brain Trauma in Sports May Cause a New Disease That Mimics ALS", BUSM press release, August 17th, 2010 3:41 pm. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ↑ Jordan, Bryant (August 12, 2013). "Obama Introduces New PTSD and Education Programs". military.com. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "Obama administration to research TBI, PTSD in new efforts Read more: Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium". fiercegovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "DoD, VA Establish Two Multi-Institutional Consortia to Research PTSD and TBI". va.gov. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- 1 2 "Fact Sheet: Largest federal grant in VCU's history". spectrum.vcu.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- 1 2 "VCU to lead major study of concussions". grpva.com. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- 1 2 "Brain trust - the US consortia tacking military PTSD and brain injury". army-technology.com. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 "DOD partners to combat brain injury". army.mil. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "RTI to research mild traumatic brain injury effects in US soldiers". army-technology.com. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ Warden D. Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006; 21 (5): 398-402.

- ↑ "DoD Worldwide Numbers for TBI". dvbic.dcoe.mil. Retrieved 4 Feb 2013.

- ↑ Scholten JD, Sayer NA, Vanderploeg RD, Bidelspach DE, Cifu DX (2012). "Analysis of US Veterans Health Administration comprehensive evaluations for traumatic brain injury in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Veterans". Brain Inj. 26 (10): 1177–84. doi:10.3109/02699052.2012.661914. PMID 22646489.

- ↑ Taylor BC, Hagel EM, Carlson KF, Cifu DX, Cutting A, Bidelspach DE, Sayer NA (2012). "Prevalence and costs of co-occurring traumatic brain injury with and without psychiatric disturbance and pain among Afghanistan and Iraq War Veteran V.A. users". Med Care. 50 (4): 342–6. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a558. PMID 22228249.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: The Obama Administration's Work to Honor Our Military Families and Veterans". whitehouse.gov. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: VCU will lead $62 million study of traumatic brain injuries in military personnel". news.vcu.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ About Us Archived December 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine., Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Virginia Commonwealth University. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ↑ Schwarz, Alan (2009-09-29). "Dementia Risk Seen in Players in N.F.L. Study". The New York Times, U.S.A. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- ↑ McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Kutcher JS, Jordan BD, Gardner A (2013). "What is the evidence for chronic concussion-related changes in retired athletes: behavioural, pathological and clinical outcomes?". Br J Sports Med. 47 (5): 327–330. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092248. PMID 23479493.

- ↑ "CTE prevalent in deceased players, study shows". ESPN. 2015-10-15. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

External links

- McGrath, Ben, "The N.F.L. and the concussion crisis", The New Yorker, January 31, 2011. Includes an account of The New York Times' and Alan Schwarz's editorial focus on CTE.

- Jahnke, Art, "Looking For Trouble", Bostonia, Fall 2012.

- Interview with Dr. Janigro on S100B in football players

- sciencedaily.com, 2013/03.

- "Concussion blood test", sportsinjuryhandbook.com.

- "Retired NFL players lose brain function", livescience.com.

- PBS Frontline, "League of Denial", October 9, 2013.

- League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions, and the Battle for Truth by Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru