Church of Norway

| Church of Norway | |

|---|---|

|

Coat of arms of the Church of Norway, a cross laid over two St. Olaf's axes. Based on the coat of arms of 16th-century archbishops of Nidaros. | |

| Classification | Protestant |

| Orientation | Lutheranism |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Associations |

Lutheran World Federation, World Council of Churches, Conference of European Churches, Porvoo Communion |

| Region | Norway |

| Origin | 1537 |

| Separated from | Roman Catholic Church |

| Members | 3,799,366 baptized members[1] |

The Church of Norway (Den norske kirke in Bokmål or Den norske kyrkja in Nynorsk) is a Lutheran denomination of Protestant Christianity that serves as the "people's church"[2][3][4][5][6] and the largest church in Norway.

The church was established after the Lutheran reformation in Denmark–Norway in 1536–1537 broke ties with the Holy See. The church professes the Lutheran Christian faith, with its foundation on the Bible, the Apostles', Nicene and Athanasian Creeds, Luther's Small Catechism and the Augsburg Confession. The church is a member of the Porvoo Communion with 12 other churches, among them the Anglican churches of Europe. It has also signed some other ecumenical texts, including the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification with the Roman Catholic Church.

Until 1969, the church's name for administrative purposes was simply the "State Church" or sometimes just "the Church", whereas the constitution described it as the "Evangelical-Lutheran Church". A constitutional amendment of May 21, 2012 designates the church as "Norway's people's church" (Norges Folkekirke), with a new provision that is almost a verbatim copy of the provision for the Danish state church (folkekirken) in the Constitution of Denmark. While the church remains state-funded and integrated in the state administration with a special constitutional role, it is largely self-governing in doctrinal matters and clergy appointments.[7][8] On 27 May, 2016, Stortinget passed a new bill that establishes the Church of Norway as an independent legal entity rather than a branch of the civil service.[9][10]

Organization

State and church

Until 1845 the Church of Norway was the only legal religious organization in Norway and it was not possible to end membership in the church of Norway. "Dissenterloven" (Lov angaaende dem, der bekjende sig til den christelige Religion, uden at være medlemmer af Statskirken) was a billed passed by the Storting on 16 July 1845 that allowed the establishment of alternative religious bodies.[11][12][13] This bill was in 1969 replaced by Lov om trudomssamfunn og ymist anna.[14]

Until 2012 the constitutional head of the church was the King of Norway, who is obliged to profess himself a Lutheran. After the constitutional amendment of May 21, 2012, the church is self-governed with regard to doctrinal issues and appointment of clergy.

The Church of Norway is subject to legislation, including its budgets, passed by the Storting, and its central administrative functions are carried out by the Royal Ministry of Government Administration, Reform and Church Affairs. Bishops and priests are civil servants also after the 2012 constitutional reform. Each parish has an autonomous administration. The state itself does not administer church buildings; buildings and adjacent land instead belong to the parish as an independent public institution.[15] The Minister of Church Affairs, Trond Giske, was responsible for proposing the 2012 amendments, explaining that "the state church is retained".[2] The church itself explained that: "In 2012 the Parliament changed the constitution such that Norway no longer has a public religion. The Church of Norway can accordingly no longer be labeled as state church."[16]

A bill passed in 2016 creates the Church of Norway as an independent legal entity from 1 January 2017..[17][18]

Structure

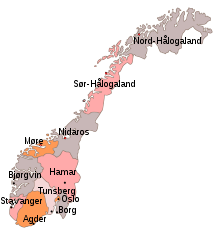

The church has an episcopal-synodal structure, with 1,284 parishes, 106 deaneries, 11 dioceses and since 2 October 2011, one area under the supervision of the presiding bishop. The dioceses are – according to the rank of the five historic sees and then according to age:

- Nidaros, seated in Trondheim, covering the counties of Nord-Trøndelag and Sør-Trøndelag. Bishops: Presiding Bishop of Nidaros and Bishop of Nidaros Cathedral Deanery Helga Haugland Byfuglien, Bishop of Nidaros Tor Singsaas.

- Bjørgvin, seated in Bergen, covering the counties of Hordaland and Sogn og Fjordane. Bishop: Halvor Nordhaug.

- Oslo, seated in Oslo, covering Oslo and parts of the county of Akershus. Bishop: Ole Christian Kvarme.

- Stavanger, seated in Stavanger, covering the county of Rogaland. Bishop: Erling J. Pettersen.

- Hamar, seated in Hamar, covering the counties of Hedmark and Oppland. Bishop: Solveig Fiske.

- Nord-Hålogaland, seated in Tromsø, covering the counties of Troms and Finnmark, and also Svalbard. Bishop: Olav Øygard.

- Agder og Telemark, seated in Kristiansand, covering the counties of Vest-Agder, Aust-Agder and Telemark. Bishop: Stein Reinertsen.

- Tunsberg, seated in Tønsberg, covering the counties of Vestfold and Buskerud. Bishop: Per Arne Dahl.

- Sør-Hålogaland, seated in Bodø, covering the county of Nordland. Bishop: Tor Berger Jørgensen.

- Borg, seated in Fredrikstad, covering the county of Østfold and parts of the county of Akershus. Bishop: Atle Sommerfeldt.

- Møre, seated in Molde, covering the county of Møre og Romsdal. Bishop: Ingeborg Midttømme.

Governing bodies

The General Synod of the Church of Norway, which convenes once a year, is the highest representative body of the church. It consists of 85 representatives, of whom seven or eight are sent from each of the dioceses. Of these, four are lay members appointed by the congregations; one is a lay member appointed by church employees; one is a member appointed by the clergy; and the bishop. In addition, one representative from the Sami community in each of the two northernmost dioceses, representatives from the three theological seminaries, representatives from the youth council. Other members of the national council are also members of the general synod.

The national council, the executive body of the synod, is convened five times a year and comprises 15 members, of whom ten are lay members, four are clergy and one is the presiding bishop. It prepares matters for decision-making elsewhere and puts those decisions into effect. The council also has working and ad hoc groups, addressing issues such as church service, education and youth issues.

The Council on Ecumenical and International Relations deals with international and ecumenical matters, and the Sami Church Council is responsible for the Church of Norway's work among the country's indigenous Sami people.

The bishops' conference convenes three times a year, and consists of the twelve bishops in the church. It issues opinions on various issues related to church life and theological matters.

The church also convenes committees and councils both at the national level (such as the Doctrinal Commission (Den norske kirkes lærenemnd),[19] and at diocesan and local levels, addressing specific issues related to education, ecumenical matters, the Sami minority and youth.

There are 1,600 Church of Norway churches and chapels. Parish work is led by a priest and an elected parish council. There are more than 1,200 clergy (in 2007 20.6% were women ministers) in the Church of Norway. The Church of Norway does not own church buildings, which are instead owned by the parish and maintained by the municipality.

Worship

The focus of church life is the Sunday Communion and other services, most commonly celebrated at 11:00 a.m. The liturgy is similar to that in use in the Roman Catholic Church. The language is entirely Norwegian, apart from the Kyrie Eleison, and the singing of hymns accompanied by organ music is central. A priest (often with lay assistants) celebrates the service, wearing an alb and stole. In addition, a chasuble is worn by the priest during the Eucharist and, increasingly, during the whole service.

The Church of Norway baptises children, usually infants and usually as part of ordinary Sunday services.

This is a summary of the liturgy for High Mass:[20][21]

- Praeludium

- Opening Hymn

- Greeting

- Confession of Sin

- Kyrie

- Gloria[22] (This may be omitted during Lent)

- Collect of the Day

(If there is a baptism it together with the Apostle's Creed may take place here or after the Sermon)

- First Lesson (Old Testament, an Epistle, the Acts of the Apostles or the Revelation to John)[23]

- Hymn of Praise

- Second Lesson (An Epistle, the Acts of the Apostles, the Revelation to John or a Gospel)

- Apostle's Creed

- Hymn before the Sermon

- Sermon (concluding with the Gloria Patri)

- Hymn after the Sermon

- Church Prayer (i.e., Intercessions)

(If there is no Communion, i.e., the Eucharist, the service concludes with the Lord's Prayer, an optional Offering, the Blessing and a moment of silent prayer)

- Hymn before the Communion

- Threefold Dialogue and Proper Preface

- Sanctus

- Prayer before the Lord's Supper,

- Lord's Prayer

- Words of Institution

- Agnus Dei

- Reception of Communion

- Prayer of Thanksgiving after Communion

- Blessing

- Silent Prayer (as the church bell is toned nine(3x3)times)

- Postludium

History

Origin

The Church of Norway traces its origins to the introduction of Christianity to Norway in the 9th century. Norway was Christianized as a result of missions from both the British Isles (by Haakon I of Norway and Olaf I of Norway), and from the Continent (by Ansgar). It took several hundred years to complete the Christianization, culminating on 29 July 1030 with the Battle of Stiklestad, when King Olaf II of Norway was killed. One year later, on 3 August 1031, he was canonised in Nidaros by Bishop Grimkell, and few years later enshrined in Nidaros Cathedral. The cathedral with its shrine to St. Olav became the major Nordic place of pilgrimage until the Lutheran reformation in 1537. The whereabouts of Saint Olaf's grave have been unknown since 1568.

Saint Olaf is traditionally regarded as being responsible for the final conversion of Norway to Christianity, and is still seen as Norway's patron saint and "eternal king" (Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae). The Nordic churches were initially subordinate to the Archbishop of Bremen, until the Nordic Archdiocese of Lund was established in 1103. The separate Norwegian Archdiocese of Nidaros (in today's Trondheim) was created in 1152, and by the end of the 12th century covered all of Norway, parts of present Sweden, Iceland, Greenland, the Isle of Man, the Orkney Islands, the Shetland Islands, the Faroe Islands, and the Hebrides.

Another site of medieval pilgrimage in Norway was the island of Selja on the northwest coast, with its memories of Saint Sunniva and its three monastery churches with Celtic influence, similar to Skellig Michael.

Reformation

The Reformation in Norway was accomplished by force in 1537 when Christian III of Denmark and Norway declared Lutheranism as the official religion of Norway and Denmark, sending the Roman Catholic archbishop, Olav Engelbrektsson, into exile in Lier in the Netherlands (now in Belgium). Catholic priests were persecuted, monastic orders were suppressed, and the crown took over church property, while some churches were plundered and abandoned, even destroyed. Bishops (initially called superintendents) were appointed by the king. This brought forth tight integration between church and state. After the introduction of absolute monarchy in 1660 all clerics were civil servants appointed by the king, but theological issues were left to the hierarchy of bishops and other clergy.

When Norway regained national independence from Denmark in 1814, the Norwegian Constitution recognized the Lutheran church as the state church.

The pietism movement in Norway (embodied to a great extent by the Haugean movement fostered by Hans Nielsen Hauge) has served to reduce the distance between laity and clergy in Norway. In 1842, lay congregational meetings were accepted in church life, though initially with limited influence. In following years, a number of large Christian organizations were created; they still serve as a "second line" in Church structure. The most notable of these are the Norwegian Missionary Society and the Norwegian Lutheran Mission.

During World War II, after Vidkun Quisling became Minister President of Norway and introduced a number of controversial measures such as state-controlled education, the Church's bishops and the vast majority of the clergy disassociated themselves from the government in the Foundations of the Church (Kirkens Grunn) declaration of Easter 1942, stating that they would only function as pastors for their congregations, not as civil servants. The bishops were interned with deposed clergy and theological candidates from 1943, but congregational life continued more or less as usual. For three years the Church of Norway was a church free of the State.

Since World War II, a number of structural changes have taken place within the Church of Norway, mostly to institutionalize lay participation in the life of the church.

Current issues

| Year | Population | Church of Norway Members | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 4,503,436 | 3,869,147 | 85.9% |

| 2005 | 4,640,219 | 3,938,723 | 84.9% |

| 2006 | 4,681,134 | 3,871,006 | 82.7% |

| 2007 | 4,737,171 | 3,873,847 | 81.8% |

| 2008 | 4,799,252 | 3,874,823 | 80.7% |

| 2009 | 4,858,199 | 3,848,841 | 79.2% |

| 2010 | 4,920,305 | 3,835,477 | 78.0% |

| 2011 | 4,985,870 | 3,832,679 | 76.9% |

| 2012 | 5,051,275 | 3,829,300 | 75.8% |

| 2013 | 5,109,056 | 3,843,721 | 75.2% |

| 2014 | 5,165,802 | 3,835,973 | 74.3% |

| 2015 | 5,213,985 | 3,799,366 | 72.9%[1] |

Norwegians are registered at baptism as members of the Church of Norway, many remain in the state church to be able to use services such as baptism, confirmation, marriage and burial, rites which have strong cultural standing in Norway.

72.9% of Norwegians were members of the state Church of Norway as of the end of 2015, a 1.4% drop compared to the year before and down about 12% from ten years earlier. However, only 20% of Norwegians say that religion occupies an important place in their life (according to a recent Gallup poll), making Norway one of the most secular countries of the world (only in Estonia, Sweden and Denmark were the percentages of people who considered religion to be important lower), and only about 3% of the population attends church services or other religious meetings more than once a month.[24] Baptism of infants fell from 96.8% in 1960 to 57.8% in 2015, while the proportion of confirmands fell from 93% in 1960 to 61.5% in 2015.[1][25] The proportion of weddings to be celebrated in the Church of Norway fell from 85.2% in 1960 to 34.5% in 2015.[1][26] In 2015 90.4% of all funerals took place in the Church of Norway.[1] A survey conducted by Gallup International in 65 countries in 2005 found that Norway was the least religious among the Western countries surveyed, with only 36% of the population considering themselves religious, 9% considering themselves atheist and 46% considering themselves "neither religious nor atheist".[27]

In spite of the relatively low level of religious practice in Norwegian society, the local clergy often play important social roles outside their spiritual and liturgical responsibilities.

By law[28] all children who have at least one parent member who is a member, automatically become members. This has been controversial, as many become members without knowing, and as this favours the Church of Norway over other churches. This law remained unchanged even after the separation of church and state in 2012.

The standpoints of certain liberal-leaning bishops on whether practising homosexuals should be permitted to serve as priests is under continuous debate and is still considered very controversial, not least among gay people. In 2000, the Church of Norway appointed the first openly partnered gay priest.[29] In 2007, a majority in the general synod voted in favour of accepting people living in same-sex relations into the priesthood.[30] In 2008, the Norwegian Parliament voted to establish same-sex civil marriages, and the bishops allowed prayers for same-sex couples.[31] In 2014 a proposed liturgy for same-sex marriages was rejected by the general synod.[32] This question created much unrest in the Church of Norway and seems to serve as a trigger for conversions to independent congregations and other churches.[33][34] In 2015, the Church of Norway voted to allow same-sex marriages.[35] On 11 April 2016, this was ratified and same-sex marriages may be performed.[36]

Legal status

On 21 May 2012, the Norwegian Parliament passed a constitutional amendment for the second time (such amendments must be passed twice in separate parliaments to come into effect) that granted the Church of Norway increased autonomy, and states that "the Church of Norway, an Evangelical-Lutheran church, remains Norway's people's church, and is supported by the State as such" ("people's church" or folkekirke is also the name of the Danish state church, Folkekirken), replacing the earlier expression which stated that "the Evangelical-Lutheran religion remains the public religion of the State." The constitution also says that Norway's values are based on its Christian and humanist heritage, and according to the Constitution, the king is required to be Lutheran. The government will still provide funding for the church as it does with other faith-based institutions, but the responsibility for appointing bishops and provosts will now rest with the church instead of the government. Prior to 1997, the appointments of parish priests and residing chaplains was also the responsibility of the government, but the church was granted the right to hire such clergy directly with the new Church Law of 1997. The 2012 amendment implies that the church's own governing bodies, rather than the Council of State, appoints bishops. The government and the parliament no longer have an oversight function with regard to doctrinal issues.[37][38]

After the changes in 1997 and 2012, all clergy remain civil servants (state employees), the central and regional church administrations remain a part of the state administration, the Church of Norway is regulated by its own law (kirkeloven) and all municipalities are required by law to support the activities of the Church of Norway and municipal authorities are represented in its local bodies. The amendment was a result of a compromise from 2008. Minister of Church Affairs Trond Giske then emphasized that the Church of Norway remains Norway's state church, stating that "the state church is retained. Neither the Labour Party nor the Centre Party had a mandate to agree to separate church and state."[39] Of the government parties, the Labour Party and the Centre Party supported a continued state church, while only the Socialist Left Party preferred a separation of church and state, although all parties eventually voted for the 2008 compromise.[40][41]

The final amendment passed by a vote of 162–3. The three dissenting votes, Lundteigen, Ramsøy, and Toppe, were all from the Centre Party.[42]

See also

- List of cathedrals in Norway

- Sami Church Council

- Evangelical Lutheran Free Church of Norway

- Lutheran World Federation

- Sjømannskirken

- Nordic Catholic Church

- Other current and former Nordic Evangelical-Lutheran churches

- Church of Sweden – Svenska kyrkan

- Church of Denmark – Folkekirken

- Church of Iceland – Þjóðkirkjan

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland –

- In Finnish: Suomen evankelis-luterilainen kirkko

- In Swedish: Evangelisk-lutherska kyrkan i Finland

- Church of the Faroe Islands – Fólkakirkjan

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Church of Norway, 2015 4.5.2016 Statistics Norway

- 1 2 Løsere bånd, men fortsatt statskirke, ABC Nyheter

- ↑ Staten skal ikke lenger ansette biskoper, NRK

- ↑ Slik blir den nye statskirkeordningen

- ↑ I dag avvikles statskirken (State church will be abolished today), Dagbladet, published 14 May 2012, accessed online 24 October 2015.

- ↑ State church in Norway?, Church of Norway, published, 6 March 2015, accessed 24 October 2015.

- ↑ https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1814-05-17

- ↑ Staten skal ikke lenger ansette biskoper, NRK

- ↑ Lov om endringer i kirkeloven (omdanning av Den norske kirke til eget rettssubjekt m.m.), Bill passed on 27 May 2016 regarding the Church as a legal entity, accessed 28 June, 2016.

- ↑ Reform for the separation of church and state, Royal Ministry of Culture, accessed 28 June 2016.

- ↑ https://snl.no/dissenter

- ↑ Unstad, Live: Religion, nasjonalisme og borgerdannelse. Religion og norsk nasjonal identitet – en analyse av dissenterlovene av 1845 og 1891. Master thesis, University of Oslo, 2010.

- ↑ https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kud/samfunn_og_frivillighet/tro-og_livssyn/innstilling_om_lov_om_trossamfunn_avgitt_av_dissenterlovkomiteen_1962_.pdf

- ↑ https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1969-06-13-25

- ↑ NOU 2006: 2: Staten og Den norske kirke [The State and the Church of Norway]. Utredning fra Stat – kirke-utvalget oppnevnt ved kongelig resolusjon av 14. mars 2003. (Official report to the Minister of Culture available online).

- ↑ Er det statskirke i Norge, Den norske kirke, Kirkerådet, 3 March 2015, accessed 31 October 2015. Translated from original: "I 2012 endret Stortinget grunnloven slik at Norge ikke lenger har noen offentlig religion. Den norske kirke kan derfor ikke lenger betegnes «statskirken»."

- ↑ Offisielt frå statsrådet 27. mai 2016 regjeringen.no «Sanksjon av Stortingets vedtak 18. mai 2016 til lov om endringer i kirkeloven (omdanning av Den norske kirke til eget rettssubjekt m.m.) Lovvedtak 56 (2015-2016) Lov nr. 17 Delt ikraftsetting av lov 27. mai 2016 om endringer i kirkeloven (omdanning av Den norske kirke til eget rettssubjekt m.m.). Loven trer i kraft fra 1. januar 2017 med unntak av romertall I § 3 nr. 8 første og fjerde ledd, § 3 nr. 10 annet punktum og § 5 femte ledd, som trer i kraft 1. juli 2016.»

- ↑ Lovvedtak 56 (2015–2016) Vedtak til lov om endringer i kirkeloven (omdanning av Den norske kirke til eget rettssubjekt m.m.) Stortinget.no

- ↑ http://www.kirken.no/?event=doLink&famID=240 (Norwegian)

- ↑ http://www.kirken.no/?event=doLink&famID=9252 (Norwegian)

- ↑ "Church of Norway". Church of Norway. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ Only the first two verses of the Gloria are used.

- ↑ It is preceded by the singing of the acclamation: "God be praised! Halleluja. Halleluja. Halleluja."

- ↑ Religiøsitet og kirkebesøk (Religion and church attendance); Forskning.no, published 2005, retrieved Februar 23, 2014.

- ↑ Basics and statistics Church of Norway

- ↑ Marriages and divorces, 2013 20.2.2014 Statistics Norway

- ↑ Lønnå, Eline; Kristin Rødland. "Nordmenn minst religiøse". Klassekampen (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ↑ "Lov om Den norske kirke (kirkeloven) - Lovdata". Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ "Lutheran Church of Norway Appoints Practicing Homosexual". Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ↑ "Church of Norway ready to ordain same-sex priests". 2007-11-24. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ↑ "Norwegian bishops consider special liturgy for gay couples". Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ↑ Kirkemøtet avviste liturgi for homofile (visited 27.04.15)

- ↑ "Kirkelig avskalling". Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ Normisjon vil utvikle menigheter (visited 27.04.15)

- ↑ Gaystarnews: Norway bishops open doors to gay church weddings

- ↑ "Church of Norway Approves Gay Marriage After 20 Years of Internal Debate". Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ↑ "Kongeriket Norges Grunnlov - Lovdata". lovdata.no. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ↑ Staten skal ikke lenger ansette biskoper, NRK

- ↑ "Løsere bånd, men fortsatt statskirke - ABC Nyheter". Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ NRK. "Ap vil beholde statskirken". NRK. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ "- Tilfreds med statskirke-forlik". Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ Her vedtar Stortinget å avvikle statskirken TV2. 21 May 2012

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Church of Norway. |

- Official website

- Churches in Norway, locator (Norwegian)