Coffee production in India

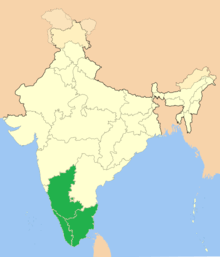

Coffee production in India is dominated in the hill tracts of South Indian states, with the state of Karnataka accounting 71% followed by Kerala 21% and Tamil Nadu 5% of production of 8,200 tonnes. Indian coffee is said to be the finest coffee grown in the shade rather than direct sunlight anywhere in the world.[1] There are approximately 250,000 coffee growers in India; 98% of them are small growers.[2] As of 2009, the production of coffee in India was only 4.5% of the total production in the world. Almost 80% of the country's coffee production is exported.[3] Of that which is exported, 70% is bound for Germany, Russian federation, Spain, Belgium, Slovenia, United States, Japan, Greece, Netherlands and France, and Italy accounts for 29% of the exports. Most of the export is shipped through the Suez Canal.[1]

Coffee is grown in three regions of India with Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu forming the traditional coffee growing region of India, followed by the new areas developed in the non-traditional areas of Andhra Pradesh and Orissa in the eastern coast of the country and with a third region comprising the states of Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Tripura, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh of Northeastern India, popularly known as “Seven Sister States of India".[4]

Indian coffee, grown mostly in southern India under monsoon rainfall conditions, is also termed as “Indian monsooned coffee". Its flavour is defined as: "The best Indian coffee reaches the flavour characteristics of Pacific coffees, but at its worst it is simply bland and uninspiring”.[5] The two well known species of coffee grown are the Arabica and Robusta. The first variety that was introduced in the Baba Budan Giri hill ranges of Karnataka in the 17th century[6] was marketed over the years under the brand names of Kent and S.795.

History

Coffee growing has a long history that is attributed first to Ethiopia and then to Arabia, mostly to Yemen. The earliest history is traced to 875 AD according to the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, and the original source to Ethiopia (Abyssinia) from where it was brought to Arabia in the 15th century. The Indian context started with an Indian Muslim saint, Baba Budan,[2][7] while on a pilgrimage to Mecca, smuggled seven coffee beans (by tying it around his waist) from Yemen to Mysore in India and planted them on the Chandragiri Hills (1,829 metres (6,001 ft)), now named after the saint as Baba Budan Giri (‘Giri’ means “hill”) in Chikkamagaluru district. It was considered an illegal act to take out green coffee seed out of Arabia. As number seven is a sacrosanct number in Islamic religion, the saint’s act of carrying seven coffee beans was considered a religious act.[6] This was the beginning of coffee industry in India, and in particular, in the then state of Mysore, now part of the Karnataka State. This was an achievement of considerable bravery of Baba Budan considering the fact that Arabs had exercised strict control over its export to other countries by not permitting coffee beans to be exported in any form other than as in a roasted or boiled form to prevent germination.[8]

Systematic cultivation soon followed Baba Budan’s first planting of the seeds, in 1670, mostly by private owners and the first plantation was established in 1840 around Baba Budan Giri and its surrounding hills in Karnataka. It spread to other areas of Wynad (now part of Kerala), the Shevaroys and Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu. With British colonial presence taking strong roots in India in the mid 19th century, coffee plantations flourished for export. The culture of coffee thus spread to South India rapidly.

Initially, Arabica was popular. However, as result of serious infestation caused to this species by coffee rust, an alternative robust species of coffee, appropriately named as robusta and another hybrid between liberica and Arabica, a rust-tolerant hybrid variety of Arabica tree became popular. This is the most common variety of coffee that is grown in the country with Karnataka alone accounting for 70% of production of this variety.[7][8]

In 1942, the government decided to regulate the export of coffee and protect the small and marginal farmers by passing the Coffee VII Act of 1942, under which the Coffee Board of India got established, operated by the Ministry of Commerceand Industry.[2] The government dramatically increased their control of coffee exports in India and pooled the coffees of its growers. In doing so, they reduced the incentives for farmers to produce high-quality coffee, so quality became stagnant.[2]

Over the last 50 years, coffee production in India has grown by over 15 percent.[9] From 1991, economic liberalisation took place in India, and the industry took full advantage of this and cheaper labour costs of production.[10] In 1993, a monumental Internal Sales Quota (ISQ) made the first step in liberalising the coffee industry by entitling coffee farmers to sell 30% of their production within India.[2] This was further amended in 1994 when the Free Sale Quota (FSQ) permitted large and small scale growers to sell between 70% and 100% of their coffee either domestically or internationally.[2] A final amendment in September 1996 saw the liberalisation of coffee for all growers in the country and a freedom to sell their produce wherever they wished.[2]

Coffee Production in Araku Region of Eastern Ghats of Andhra Pradesh[11]

Coffee was first introduced in Andhra Pradesh in 1898 by Mr. Brodi, a Brtisher in Pamuleru valley in East Godavari district. Subsequently it spread over to Pullangi (East Godavari district), Araku Valley and Gudem of Visakhapatnam agency tracks. In 1920s even though it spread over to Ananthagiri in Araku valley and Chintapalli areas, coffee cultivation remained dormant for a long time. In 1960s, the Andhra Pradesh Forest Department developed coffee plantations in 10100 acres in Reserve forest areas. These plantations were handed over to the A.P. Forest Development Corporation in the year 1985. In the year 1956 after the formation of Andhra Pradesh Girijan Cooperative Corporation Limited (GCC), the Coffee Board identified GCC for promoting coffee plantations. Since then GCC started making efforts to develop coffee plantation through local tribal famers. A separate coffee wing was carved out in GCC and promoting coffee in around 4000 hectares taken up. Thus, the coffee grown in Araku valley by the tribal farmers under organic practices attained recognition as “Araku coffee”. After 1985, GCC promoted another organization by name “Girijan Coop. Plantation Development Corporation” (GCPDC) exclusively to develop coffee plantations in tribal areas. All the plantations developed by GCC and GCPDC were handed over to the tribal farmers @ 2 acres to each family. In July, 1997 the employees working in GCPDC were deployed to ITDA and coffee expansion was taken up under Five year Plan and MGNREGS. Thus presently the coffee cultivation reached 1 lakh acres and maintained by the tribal farmers. In India, while coffee plantations were well developed over the last century in Western ghats, expansion of coffee in Eastern ghats is still to develop. Coffee is grown under organic practices under shades of Mango, Jackfruit, Banana and silver oak trees. It also helps in environmental conservation and ecological balances. Around 1 lakh tribal families living in this region are getting financially stabilized through coffee cultivation. The more welcoming development is that the tribal famers have given up their traditional “Podu” cultivation and now switched over to coffee cultivation on a large scale. It is not an exaggeration to say that in Araku region, the coffee cultivation is not only helping conservation of forest and ecological balances but also as a viable high economic pursuit to the tribal farmers. The coffee cultivated in this region at an altitude of 900 to 1100 m MSL is having unique qualities due to medium acidity in soil. During the year 2015-16 GCC collected 1400 M.Ts of coffee, marketed the same through E-auctions

Production

Background

Like in Ceylon, coffee production in India declined rapidly from the 1870s and was massively outgrown by the emerging tea industry. The devastating coffee rust affected the output of coffee to the point that the costs of production saw coffee plantations in many parts replaced with tea plantations.[12] However, the coffee industry was not as affected by this disease as in Ceylon, and although overshadowed in scale by the tea industry, India was still one of the strongholds of coffee production in the British Empire along with British Guiana. In the period 1910–12, the area under coffee plantation was reported to be 203,134 acres (82,205 ha) in the southern states, and was mostly exported to England.

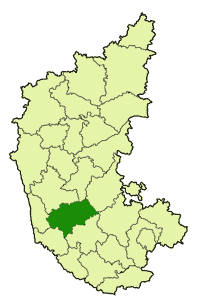

In the 1940s, Indian filter coffee, a sweet milky coffee made from dark roasted coffee beans (70%–80%) and chicory (20%–30%) became a commercial success. It was especially popular in the southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The most commonly used coffee beans are Arabica and Robusta grown in the hills of Karnataka (Kodagu, Chikkamagaluru and Hassan), Kerala (Malabar region) and Tamil Nadu (Nilgiris District, Yercaud and Kodaikanal).

Coffee production in India grew rapidly in the 1970s, increasing from 68,948 tonnes in 1971–72 to 120,000 tonnes in 1979–80 and grew by 4.6 percent in the 1980s.[13] It grew by more than 30 percent in the 1990s, rivalled only by Uganda in the growth of production.[14][15] By 2007, organic coffee was grown in about 2,600 hectares (6,400 acres) with an estimated production of about 1700 tonnes.[16] According to the 2008 statistics published by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the area of coffee green harvested in India was 342,000 hectares (850,000 acres),[17] with yield estimates of 7,660 hectogram/ha,[18] forming a total production estimate of 262,000 tonnes.[19]

There are approximately 250,000 coffee growers in India; 98% of them are small growers.[2] Over 90 percent of them are small farms consisting of 10 acres (4.0 ha) or fewer. According to published statistics for 2001–2002, the total area under coffee in India was 346,995 hectares (857,440 acres) with small holdings of 175,475 accounting for 71.2%. The area under large holding of more than 100 hectares (250 acres) was 31,571 hectares (78,010 acres) (only 9.1% of all holdings) only under 167 holdings. The area under less than 2 hectares (4.9 acres) holdings was 114,546 hectares (283,050 acres) (33% of the total area) among 138,209 holders.[2]

| Size of holdings | Numbers (2001–2002) | Area of holding |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 10 ha 10 hectares (25 acres) | 175,475 | 247,087 hectares (610,570 acres) |

| Between 10 and 100 ha and above | 2833 | 99,908 hectares (246,880 acres) |

| Total | 178,308 | 346,995 hectares (857,440 acres) |

The most important areas of production are in the southern Indian states of Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu which accounted for over 92 percent of India's coffee production in the 2005–2006 growing season. In this same season, India exported over 440,000 pounds (200,000 kg) of coffee, with over 25 percent destined for Italy. Traditionally, India has been a noted producer of Arabica coffee but in the last decade robusta beans are growing substantially due to high yields, which now account for over 60 percent of coffee produced in India. The domestic consumption of coffee increased from 50,000 tonnes in 1995 to 94,400 tonnes in 2008.[20]

According to the statistics provided by the Coffee Board of India, the estimated production of Robusta and Arabica coffee for the "Post Monsoon Estimation 2009–10" and "Post Blossom Estimation 2010–11" in different states accounted for a total of 308,000 tonnes and 289,600 tonnes, respectively.[21] As of 2010, between 70% and 80% of Indian grown coffee is exported overseas.[9][22]

Growing conditions

All coffees grown in India are grown in shade and commonly with two tiers of shade. Often inter-cropped with spices such as cardamom, cinnamon, clove, and nutmeg, the coffees gain aromatics from the inter-cropping, storage, and handling functions.[23] Growing altitudes range between 1,000 m (3,300 ft) to 1,500 m (4,900 ft) above sea level for Arabica (premier coffee), and 500 m (1,600 ft) to 1,000 m (3,300 ft) for Robusta (though of lower quality, it is robust to environment conditions).[2][16] Ideally, both Arabica and Robusta are planted in well drained soil conditions that favour rich organic matter that is slightly acidic (pH 6.0–6.5).[16] However, India's coffees tend to be moderately acidic which can lead to either a balanced and sweet taste, or a listless and inert one.[23] Slopes of Arabica tend to be gentle to moderate, while Robusta slopes are gentle to fairly level.[16]

- Blooming and maturing

Blooming is the time when coffee plants bloom with white flowers which last for about 3–4 days (termed "evanescent" period) before they mature into seeds. When coffee plantations are in full bloom it is a delightful sight to watch. The time period between blooming and maturing of the fruit varies appreciably with the variety and the climate; for the Arabica, it is about seven months, and for the Robusta, about nine months. The fruit is gathered by hand when it is fully ripe and red-purple in colour.[24][25][26]

- Climatic conditions

Ideal climatic conditions to grow coffee are related to temperature and rainfall; temperatures in the range of 73 °F (23 °C) and 82 °F (28 °C) with rainfall incidence in the range of 60–80 inches (1.5–2.0 m) followed by a dry spell of 2–3 months suit the Arabica variety. Cold temperatures closer to freezing conditions are not suitable to grow coffee. Where the rainfall is less than 40 inches (1.0 m), providing irrigation facilities is essential. In the tropical region of the south Indian hills, these conditions prevail leading to coffee plantations flourishing in large numbers.[27] Relative humidity for Arabica ranges 70–80% while for Robusta it ranges 80–90%.[16]

- Coffee diseases

The common disease to which the coffee plants are subjected to in India is on account of fungus growth. This fungus is called the Hemileia vastatrix, an endophytous that grows within the matter of the leaf; effective cure has not been discovered to eliminate this. The second type of disease is known as the coffee rot, which has caused severe damages during the rainy season, particularly to plantations in Karnataka. Pellicularia koleroga was the name given to this rot or rust, which turns the leaves into black colour due to the coverage by a slimy gelatinous film. It is now classified as Ceratobasidium noxium This causes the coffee leaves and the cluster of coffee berries to drop off to the ground.[7] Snakes such as cobras can also cause a nuisance to coffee plantations in India.

Processing

Processing of coffee in India is accomplished using two methods, dry processing and wet processing. Dry processing is the traditional method of drying in the sun which is favoured for its flavour producing characteristics. In the wet processing method, coffee beans are fermented and washed, which is the preferred method for improved yields. As to the wet processing, the beans are subject to cleaning to segregate defective seeds. The beans of different varieties and sizes are then blended to derive the best flavour. The next procedure is to roast either through roasters or individual roasters. Then the roasted coffee is ground to appropriate sizes.[1]

Varieties

The four main botanical cultivars of India's coffee include Kent, S.795, Cauvery, and Selection 9. In the 1920s, the earliest variety of Arabica grown in India was named Kent(s)[16] after the Englishman L.P. Kent, a planter of the Doddengudda Estate in Mysore.[28] Probably the most commonly planted Arabica in India and Southeast Asia is S.795,[29] known for its balanced cup and subtle flavour notes of mocca. Released during the 1940s, it is a cross between the Kents and S.288 varieties.[29] Cauvery, commonly known as Catimor, is a derivative of a cross between Caturra with Hybrido-de-Timor, while the award-winning Selection 9 is a derivative from the crossing between Tafarikela and Hybrido-de-Timor.[16] The dwarf and semi-dwarf hybrids of San Ramon and Caturra were developed to meet the demands for high density plantings.[30] The Devamachy hybrid (C. arabica and C. canephora) was first discovered around 1930 in India.[31]

The Indian Coffee Association's weekly auction includes such varieties as Arabica Cherry, Robusta Cherry, Arabica Plantation, and Robusta Parchment.[32]

Regional logos and brands include: Anamalais, Araku valley, Bababudangiris, Biligiris, Brahmaputra, Chikmagalur, Coorg, Manjarabad, Nilgiris, Pulneys, Sheveroys, Travancore, and Wayanad. There are also several specialty brands such as Monsooned Malabar AA, Mysore Nuggets Extra Bold, and Robusta Kaapi Royale.[16]

- Organic coffee

Organic coffee is produced without synthetic agro-chemicals and plant protection methods. A certification is essential by the accrediting agency for such coffee to market it (popular forms are of regular, decaffeinated, flavoured and instant coffee variety) as such since they are popular in Europe, United States and Japan. The Indian terrain and climatic conditions provide the advantages required for the growth of such coffee in deep and fertile forest soils under the two tier mixed shade using cattle manure, composting and manual weeding coupled with the horticultural operations practised in its various coffee plantations; small holdings is another advantage for such a variety of coffee. In spite of all these advantages, the certified organic coffee holdings in India, as of 2008, (there are 20 accredited certification agencies in India) was only in an area of 2,600 hectares (6,400 acres) with production estimated at 1700 tonnes. In order to promote growth of such coffee, the Coffee Board, based on field experiments, surveys and case studies has evolved many packages for adoption, supplemented with information guidelines and technical documents.[4]

Research and development

Coffee research and development efforts are well organised in India through its Coffee Research Institute, which is considered the premier research station in South East Asia. It is under the control of the Coffee Board of India, an autonomous body, under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, which was set up under an Act of the Parliament with the objective of promoting “research, development, extension, quality up gradation, market information, and the domestic and external promotion of Indian coffee.”[33] It was established near Balehonnur in Chikmagalur district of Karnataka, in the heartland of coffee plantations. Prior to establishing this institute, a temporary research unit was established in 1915 at Koppa primarily to evolve solutions to crop infestation by leaf diseases. This was followed by the field research station established by the then Government of Mysore, titled "Mysore Coffee Experimental Station," in 1925. This was handed over to the Coffee Board which was formed in 1942, and regular research started at this station from 1944. Dr L. C. Coleman is credited as the founder of coffee research in India.[34] The Coffee Board of India is an autonomous body, functioning under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. The Board serves as a friend, philosopher and guide of the coffee industry in India. Set up under an Act of the Parliament of India in the year 1942, the Board focuses on research, development, extension, quality up gradation, market information, and the domestic and external promotion of Indian coffee.

The research activities covered by the Institute constitute research in seven disciplines such as Agronomy, Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, Botany, Entomology/Nematology, Plant Physiology, Biotechnology and Post Harvest Technology with the basic aim of increasing productivity and quality of coffee grown in India. The institute has 60 scientific and technical personnel involved in research activities. The institute has a well established farm land of 130.94 hectares (323.6 acres) for carrying out crop research, out of which 80.26 hectares (198.3 acres) are dedicated to coffee research (51.32 hectares (126.8 acres) of arabica and 28.94 hectares (71.5 acres) of robusta), 10 hectares (25 acres) are used for growing CXR, 12.38 hectares (30.6 acres) are apportioned for nurseries, roads and buildings, and the balance area of 12.38 hectares (30.6 acres) is a reserve area for future expansion. The research farm has a well established network of check dams that provides a regulated water source to the plantations which offer a wide range of shade tree species under which coffee is grown, and germplasm and exotic material from all the coffee growing countries including Ethiopia which is known as the home land of Arabica. In addition, crop diversification with crops such as pepper and areca are also part of income generating programmes of the institute.[34]

Part of the institute includes a research laboratory to carry out research in identified disciplines, as well as a stocked library with books and periodicals, not only on coffee but also on other crops. Training of personnel is an important activity of the institute. The training unit of the institute conducts regular training programs for estate managers and supervisory personnel of the coffee plantations and also for the extension officers of the Coffee Board. Recognised by UNDP and USDA, the training unit of the institute is providing training to foreign nationals on coffee cultivation in which personnel from Ethiopia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Nestle Singapore have been trained.[34]

In addition, a Plant Tissue Culture & Biotechnology division, established in Mysore, is carrying out exclusive research in bio-technology and molecular biology to supplement/complement the conventional breeding programs in developing high yielding, pest and disease resistant varieties. The Coffee Board of India maintains a Quality Control Division in its head office in Bengaluru which plays an active role in collaborating with other research disciplines in upgrading the “quality of coffee in the cup.”[34]

Regional research stations

To cover research specific to each coffee growing region covering different agro-climatic conditions, the following five research stations are fully functional under the overall control of the Central Coffee Research Institute.[34][35]

- Coffee Research Sub-station (CRSS), Chettalli in Kodagu district of Karnataka, was established in 1946. The sub-station has a well equipped laboratory and covers an area of 131 hectares (320 acres) out of which 80 hectares (200 acres) is exclusive to coffee research activities.[35]

- Regional Coffee Research Station (RCRS), R.V. Nagar in Visakhapatnam district of Andhra Pradesh also covers the Orissa on the eastern coast. The research station, established in 1976 to cater to the development of coffee in non-traditional areas has an area of 30 hectares (74 acres) under coffee plantation. The objective of introducing coffee in this area was to wean away the tribal population from growing crops under the 'Podu' cultivation (shifting cultivation) in the forest areas, not only to preserve the forest ecology but also to improve the economic condition of the tribal people of the region.[35]

- Regional Coffee Research Station (RCRS), Chundale village in Wayanad district of Kerala was established primarily to develop appropriate technologies to suit the region where robusta is the dominant crop. Kerala is reckoned as the second largest coffee producing state in the country with robusta variety of coffee. The station covers an area of 116 hectares (290 acres) with 30 hectares (74 acres) of farm with an adequate laboratory support for research.[35]

- Regional Coffee Research Station (RCRS), Thandigudi in Dindigul district of Tamil Nadu. The research station was established with the sole aim of evolving suitable practices for the cultivation of coffee area in Tamil Nadu which receives major rainfall (but scanty) during the Northeast monsoon, unlike the other regions of the country. This station is spread over an area of 12.5 hectares (31 acres) including a research farm of 6.5 hectares (16 acres) with laboratory facilities.[35]

- Regional Coffee Research Station (RCRS), Diphu in Karbi Anglon district of Assam was established to support coffee plantations which were established in the Northeast region in 1980 to provide an alternate, economically viable agricultural practice to the shifting or jhum cultivation, widely practised by the tribals in the forested hills, which was a cause of concern to preserve the ecology of the region. This regional station is spread over an area of 25 hectares (62 acres).[35]

Popularity

The India Coffee House chain was first started by the Coffee Board in early 1940s, during British rule. In the mid-1950s, the Board closed down the Coffee Houses, due to a policy change. However, the discharged employees then took over the branches, under the leadership of the then communist leader A. K. Gopalan and renamed the network as Indian Coffee House. The first Indian Coffee Workers Co-Operative Society was established in Bengaluru on 19 August 1957. The first Indian Coffee House was opened in New Delhi on 27 October 1957. Gradually, the Indian Coffee House chain expanded across the country, with branches in Pondicherry, Thrissur, Lucknow, Nagpur, Jabalpur, Mumbai, Kolkata, Tellicherry and Pune Tamil Nadu by the end of 1958. These coffee houses in the country are run by 13 cooperative societies, which are governed by managing committees elected from the employees. A federation of the co-operative societies is the national umbrella organisation to lead these societies.[36][37]

However, now Coffee bars have gained in popularity with other chains such as Barista; Café Coffee Day is the country's largest coffee bar chain.[38] In the Indian home, coffee consumption is greater in south India than elsewhere.[39]

Indian coffee has a good reputation in Europe for its less acidic and sweetness of character and thus widely used in Espresso Coffee, though Americans prefer African and South American coffee, which is a more acidic and brighter variety.[6]

Selection 9 was the winner of the Fine Cup Award for best Arabica at the 2002 Flavour of India – Cupping Competition.[16] In 2004, Indian Coffee with the brand name "Tata Coffee" had the distinction of winning three gold medals at the Grand Cus De Café Competition held in Paris.[6]

Coffee Board of India

The Coffee Board of India is an organisation managed by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry of the government of India to promote coffee production in India. The board was set up by an act of parliament in 1942. Until 1995 the Coffee Board marketed the coffee of many growers from a pooled supply, but after that time coffee marketing became a private-sector activity due to the economic liberalisation in India.[40]

The Coffee Board's traditional duties include the promotion, sale and consumption of coffee in India and abroad; conducting coffee research; financial assistance to establish small coffee growers; safeguarding working conditions for labourers, and managing the surplus pool of unsold coffee.[41]

See also

![]() Coffee portal

Coffee portal

References

- 1 2 3 http://www.indiacoffee.org/coffee-statistics.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lee, Hau Leung; Lee, Chung-Yee (2007). Building supply chain excellence in emerging economies. pp. 293–94. ISBN 0-387-38428-6.

- ↑ Illy, Andrea; Viani, Rinantonio (2005). Espresso coffee: the science of quality. Academic Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-12-370371-9.

- 1 2 "Coffee Regions – India". Indian Coffee Organization. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ↑ "Indian Coffee". Coffee Research Organization. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- 1 2 3 4 Robertson, Carol (2010). The Little Book of Coffee Law. American Bar Association. pp. 77–79. ISBN 1-60442-985-2. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 Encyclopædia Britannica. "The Encyclopædia Britannica; a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature". Coffee. Archive.org. pp. 110–112. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- 1 2 Playne, Somerset; Bond, J.W.; Wright, Arnold (2004). Southern India – Its History, People, Commerce: Its History, People, Commerce, and Industrial Resources. Asian Educational Services. pp. 219–222. ISBN 81-206-1344-9.

- 1 2 Waller, J. M., Bigger, M., Hillocks, R.J. (2007). Coffee pests, diseases and their management. CABI. p. 26. ISBN 1-84593-129-7.

- ↑ Clay, Jason, W. (2004). World agriculture and the environment: a commodity-by-commodity guide to impacts and practices. Island Press. p. 74. ISBN 1-55963-370-0.

- ↑ "Araku coffee a big draw". September 16, 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of the British Empire, Volume 1. CUP. 1929. p. 462.

- ↑ Medium-term prospects for agricultural commodities: projections to the year 2000. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1994. p. 112. ISBN 92-5-103482-6.

- ↑ "The Eastern economist". 75 (2). 1980: 950–1.

- ↑ Talbot, John M. (2004). Grounds for agreement: the political economy of the coffee commodity chain. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 128. ISBN 0-7425-2629-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Coffee Regions – India". indiacoffee.org. Bengaluru, India: Coffee Board. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Area Harvested (ha)". FAO. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ↑ "Yield Harvested (hg/Ha)". FAO. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ↑ "Production (tonnes)". FAO. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ↑ "Coffee Data". Coffee Board of India. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- ↑ "Database on Coffee – May–June 2010". Coffee Board of India. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Coffee exports rise 57 pc in Jan–Nov to 2.71 L tn". The Economic Times. 1 December 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- 1 2 Davids, Ken (January 2001). "Indias". coffeereview.com. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Hau Leung Lee; Chung-Yee Lee (1991). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 158. ISBN 0-85229-529-4. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Britannica – "coffee production" article". Encyclopædia Britannica Mobile. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Chikmagalur in Karnataka, where coffee was first planted in India.". India Study Channel. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Coffee Production". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- ↑ Cramer, Pieter Johannes Samuel (1957). A Review of Literature of Coffee Research in Indonesia. IICA Biblioteca Venezuela. p. 102.

- 1 2 Neilson, Jeff; Pritchard, Bill (2009). Value chain struggles: institutions and governance in the plantation districts of South India. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 124. ISBN 1-4051-7393-9.

- ↑ Sera, T.; Soccol, C. R.; Pandey, A. (2000). Coffee biotechnology and quality: proceedings of the 3rd International Seminar on Biotechnology in the Coffee Agro-Industry, III SIBAC, Londrina, Brazil. Springer. p. 23. ISBN 0-7923-6582-8.

- ↑ Wintgens, Jean Nicolas (2009). Coffee: Growing, Processing, Sustainable Production: A Guidebook for Growers, Processors, Traders, and Researchers. Wiley-VCH. p. 64. ISBN 3-527-32286-8.

- ↑ "India coffee slightly higher on selective buying". Reuters. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Central Coffee Research Institute". India Coffee Organization. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Central Coffee Research Institute, Balehonnur". Chickmagalur, National Informatics Centre. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Regional Research Stations". Chickmagalur, National Informatics Centre. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ↑ "More than just coffee 'n snacks". The Hindu. 23 September 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Indian coffee House". Indian Coffee House. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "Cafe Coffee Day bags 8 awards at India Barista". commodityonline.com. 7 March 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Majumdar, Ramanuj (2010). Consumer Behaviour: Insights From Indian Market. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 279. ISBN 81-203-3963-0.

- ↑ "Coffee Board of India – About Us". indiacoffee.org. 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ John, K. C.; Kevin, S (2004). Traditional Exports of India: Performance and Prospects. Delhi: New Century Publications. p. 117. ISBN 81-7708-062-8.

External links

Media related to Coffee plantations in India at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Coffee plantations in India at Wikimedia Commons- Coffee Board of India