Fernandina Beach, Florida

| Fernandina Beach, Florida | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| City of Fernandina Beach | ||

|

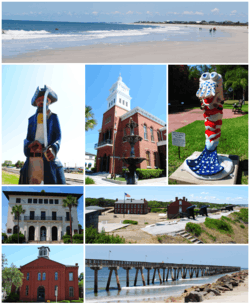

Images from top, left to right: Beach, statue of a pirate (the mascot of Fernandina Beach High School), Nassau County Courthouse (Florida), shrimp statue (representing the annual Shrimp Festival), United States Post Office, Custom House, and Courthouse (Fernandina, Florida, 1912), Fort Clinch, Old School House, Fort Clinch Pier | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): Isle of 8 Flags | ||

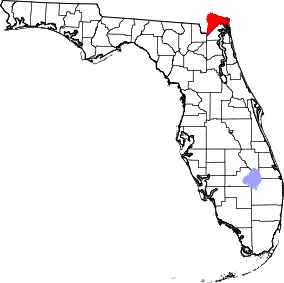

Location in Nassau County and the state of Florida | ||

Fernandina Beach, Florida Location in the U.S. | ||

| Coordinates: 30°40′10″N 81°27′42″W / 30.66944°N 81.46167°WCoordinates: 30°40′10″N 81°27′42″W / 30.66944°N 81.46167°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Florida | |

| County | Nassau | |

| Commissioner | Len Kreger | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Johnny Miller | |

| • Vice-Mayor | Robin Lentz | |

| • Commissioner | Roy Smith | |

| • Commissioner | Robin Lentz | |

| • Commissioner | Tim Poynter | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 10.7 sq mi (27.8 km2) | |

| • Land | 10.7 sq mi (27.8 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) | |

| Elevation | 25 ft (7.6 m) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 11,487 | |

| • Density | 1,073.6/sq mi (2,780.6/km2) | |

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | |

| ZIP codes | 32034-32035 | |

| Area code(s) | 904 | |

| FIPS code | 12-22175[1] | |

| GNIS feature ID | 0294308[2] | |

| Website | www.fbfl.us. | |

Fernandina Beach is a city in Nassau County in the state of Florida in the United States of America, on Amelia Island. It is the northernmost city on Florida's Atlantic coast, and is one of the principal municipalities comprising Greater Jacksonville. The area was first inhabited by the Timucuan Indian tribe. Located on Amelia Island, known as the "Isle of 8 Flags", Fernandina has had the flags of the following nations flown over it since 1562: France, Spain, Great Britain, Spain (again), the Patriots of Amelia Island, the Green Cross of Florida, Mexico, the Confederate States of America, and the United States. It is the only municipality in the United States that has flown eight different national flags.[3]

According to the 2010 census, the city population was 11,487. It is the seat of Nassau County.[4]

History

Prior to the arrival of Europeans on what is now Amelia Island, the site of the original town of Fernandina was occupied by Native Americans.[5] Native American bands associated with the Timucuan mound-building culture had settled on the island about 1000 A.D., calling it Napoyca. They remained on the island until the early 18th century, when European settlement began there. In 1736, James Oglethorpe, the governor of Georgia, ordered Fort Amelia to be built at the mouth of the St. Marys River to house a garrison of Scottish Highlanders.[6][7] The American naturalist William Bartram visited Amelia Island in 1776, noting the presence of several very large tumuli, or earthwork mounds, which the colonists called "Ogeechee mounts".[8] France, England, and Spain all had maintained a presence on the island intermittently during the 16th through 18th centuries, but the first permanent European settlement was not made until Spain took over Florida from Britain at the end of the American Revolution.[9] During later colonial times the site had gained military importance because of its deep harbor and its strategic location near the northern boundary of Spanish Florida. On January 1, 1811, Enrique White, governor of Spain's East Florida province, named the town of Fernandina, about a mile from the present city, in honor of King Ferdinand VII. On May 10 of that year,[10] Fernandina became the last town platted under the Laws of the Indies in the Western hemisphere. The town was intended as a bulwark against U.S. territorial expansion. In the following years, it was captured and recaptured by a succession of renegades and privateers. The proclamation of the Adams-Onis Treaty on February 22, 1821, two years after its signing in 1819, officially transferred Spain's territories in Florida, including Amelia Island, to the United States.[11]

The "Isle of 8 Flags"

French flag

French Huguenot explorer Jean Ribault became the first recorded European visitor to Napoyca in 1562, which he named Isle de Mai.

Spanish flag

In 1565, Spanish forces led by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés drove the French from northeastern Florida, killing Ribault and approximately 350 other French colonists.

In 1573, Spanish Franciscans established the Santa Maria mission on the island, which was named Isla de Santa Maria. The mission was abandoned in 1680 after the inhabitants refused a Spanish order to relocate. British raids forced the relocation of the Santa Catalina de Guale mission on Georgia's St. Catherines Island, to the abandoned Santa Maria mission on the island in 1685. In 1702, this mission was again abandoned when South Carolina's colonial governor, James Moore, led a joint British-Indian invasion of Florida.

British flag

Georgia's founder and colonial governor, James Oglethorpe, renamed the island "Amelia Island" in honor of Princess Amelia (1711–1786), King George II's daughter, although the island was still a Spanish possession. After establishing a small settlement on the northwestern edge of the island, Oglethorpe negotiated with Spanish colonial officials for a transfer of the island to British sovereignty. Colonial officials agreed to the transfer, but the King of Spain rescinded the agreement.

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 ratified Britain's victory over France in the Seven Years' War. Spain ceded Florida to Britain in exchange for Havana, nullifying all Spanish land grants in Florida. The Proclamation of 1763 established the St. Marys River as East Florida's northeastern boundary.

Spanish flag

Although not officially allied with the Americans during the Revolutionary War,[12] Spain cooperated with them as co-belligerents against the British in some actions.[13] In 1783, the Second Treaty of Paris ended hostilities, and under its terms Great Britain ceded East and West Florida to Spain, and all British inhabitants of the Floridas, including those on Amelia Island, had to leave within 18 months unless they swore allegiance to Spain and professed Catholicism.[14][15] In 1811, surveyor George J. F. Clarke platted the town of Fernandina, named in honor of Spain's King Ferdinand VII.[10]

Patriot Republic of Florida Flag

At the beginning of the Patriot War, with the approval of President James Madison and Georgia Governor George Mathews on 13 March 1812,[16] insurgents known as the "Patriots of Amelia Island" seized the island. After raising a Patriot flag, they replaced it with the United States flag. American gunboats under the command of Commodore Hugh Campbell maintained control of the island. On 15 May 1812, the British brig Sappho fired on Gunboat no. 168, which had fired on the loyalist merchant vessel Fernando to prevent her leaving. Outgunned, the American gunboat withdrew, which enabled several vessels to escape from the port.

Spanish flag

Spanish pressure forced the American evacuation from the island in 1813. Spanish forces erected Fort San Carlos on the island in 1816.

Latin American Patriots' Green Cross of Florida flag

Led by Gregor MacGregor in 1817, a Scottish soldier and adventurer, 55 musketeers seized Fort San Carlos, claiming the island on behalf of "the brethren of Mexico, Buenos Ayres, New Grenada and Venezuela".[17] MacGregor claimed to be Brigadier General of the armies of the United Provinces of New Grenada and Venezuela (where he had successfully fought and led troops), and General-in-Chief of the armies for the two Floridas, commissioned by the Supreme Director of Mexico.[17]

Mexican rebel flag

Spanish soldiers forced MacGregor's withdrawal, but their attempt to regain complete control was foiled by American irregulars organized by Ruggles Hubbard and former Pennsylvania congressman Jared Irwin. Hubbard and Irwin later joined forces with the French-born pirate Louis Aury, who laid claim to the island on behalf of the Republic of Mexico. U.S. Navy forces drove Aury from the island, and President James Monroe vowed to hold Amelia Island "in trust for Spain."

Confederate flag

On January 8, 1861, two days before Florida's secession, Confederate sympathizers (the Third Regiment of Florida Volunteers) took control of Fort Clinch, already abandoned by the Federal workers who had been enlarging the structure. General Robert E. Lee visited Fort Clinch in November 1861 and again in January 1862, during a survey of coastal fortifications. Since rifled cannons had made its brick defenses obsolete, he decided to withdraw the troops for better use elsewhere.

United States flag

Union forces, consisting of 28 gunboats commanded by Commodore Samuel Dupont, occupied the island on March 3, 1862, and raised the American flag. In January 1863, the first all-black regiment of former slaves recruited to fight for the Union was read Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation at Fernandina. Three weeks later they set sail up the St. Marys River to engage the Confederate forces. The Union used the fort as a base for its operations in the area for the remainder of the war.

Geography

Fernandina Beach is located at 30°24′04″N 81°16′27″W / 30.4010°N 81.2742°W,[18] approximately 25 miles (40 km) northeast of downtown Jacksonville.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 15.7 square miles (41 km2), all land. It is the northernmost city on the eastern coast of Florida.

Climate

| Climate data for Fernandina Beach, Florida (elevation 49 ft.) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63.0 (17.2) |

65.8 (18.8) |

71.2 (21.8) |

76.8 (24.9) |

83.3 (28.5) |

88.0 (31.1) |

90.6 (32.6) |

89.3 (31.8) |

85.6 (29.8) |

79.2 (26.2) |

72.2 (22.3) |

64.9 (18.3) |

77.5 (25.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 53.8 (12.1) |

56.5 (13.6) |

61.9 (16.6) |

67.7 (19.8) |

75.0 (23.9) |

80.4 (26.9) |

82.6 (28.1) |

82.1 (27.8) |

79.2 (26.2) |

72.1 (22.3) |

63.9 (17.7) |

56.3 (13.5) |

69.3 (20.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 44.5 (6.9) |

47.2 (8.4) |

52.6 (11.4) |

58.6 (14.8) |

66.7 (19.3) |

72.8 (22.7) |

74.6 (23.7) |

74.9 (23.8) |

72.8 (22.7) |

65.0 (18.3) |

55.6 (13.1) |

47.6 (8.7) |

61.1 (16.2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.42 (86.9) |

3.20 (81.3) |

3.92 (99.6) |

2.82 (71.6) |

2.31 (58.7) |

5.27 (133.9) |

5.52 (140.2) |

5.82 (147.8) |

6.91 (175.5) |

4.59 (116.6) |

2.08 (52.8) |

2.95 (74.9) |

48.81 (1,239.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.1 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 11.5 | 11.9 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 109.1 |

| Source: NOAA (1981-2010 Normals)[19][20] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,390 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,722 | 23.9% | |

| 1880 | 2,562 | 48.8% | |

| 1890 | 2,803 | 9.4% | |

| 1900 | 3,245 | 15.8% | |

| 1910 | 3,482 | 7.3% | |

| 1920 | 3,147 | −9.6% | |

| 1930 | 3,023 | −3.9% | |

| 1940 | 3,492 | 15.5% | |

| 1950 | 4,420 | 26.6% | |

| 1960 | 7,276 | 64.6% | |

| 1970 | 6,955 | −4.4% | |

| 1980 | 7,224 | 3.9% | |

| 1990 | 8,765 | 21.3% | |

| 2000 | 10,549 | 20.4% | |

| 2010 | 11,487 | 8.9% | |

| Est. 2015 | 12,339 | [21] | 7.4% |

As of the census of 2010, there were 11,487 people, 5,176 households, and 3,207 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,031.8 people per square mile (397.9/km2). There were 7,064 housing units at an average density of 449.9 per square mile (173.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 83.4% White, 11.7% African American, 0.4% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.1% from other races and 1.3% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 5.3% of the population.

Out of 4,789 households 21.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.3% were married couples living together, 12.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.0% were non-families. 30.6% of all households were made up of householders living alone and 12.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.18 and the average family size was 2.65.

In the city the population was spread out with 16.3% under the age of 18, 6.7% from 20 to 24, 20.1% from 25 to 44, 34.6% from 45 to 64, and 22.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 50.[23]

The median income for a household in the city was $45,954, and the median income for a family was $61,523. Males had a median income of $42,188 versus $35,934 for females. The per capita income for the city was $30,019. About 16% of families and 17.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.0% of those under age 18 and 13.6% of those age 65 or over.[24]

Education

The schools of Fernandina Beach are part of the Nassau County School district. They include:

- Southside Elementary School (PreK-2)

- Emma Love Hardee Elementary School (3-5)

- Fernandina Beach Middle School (6-8)

- Fernandina Beach High School (9-12)

- St Michael Academy (PreK-8)

Note: Atlantic Elementary (2nd and 3rd grades) was closed at the end of the 2008 school year. After the closing, 2nd grade was moved to Southside and 3rd grade to Emma Love. Also, the private Catholic school, St. Michael's Academy, is located in downtown Fernandina Beach. All three Fernandina Beach public schools are "A" rated by the State of Florida.

Notable people

- William B. Allen, political scientist who was chairman of the United States Commission on Civil Rights from 1988 to 1989, was born in Fernandina Beach in 1944.

- Raymond A. Brown, attorney whose clients included Black Liberation Army member Assata Shakur, boxer Rubin "Hurricane" Carter and "Dr. X" physician Mario Jascalevich.[25]

- George Rainsford Fairbanks, a Confederate Major in the U.S. Civil War, he was also a historian, lawyer and Florida State Senator. The Fairbanks House is listed on the NRHP and is operated as a bed and breakfast lodging establishment.

- David Levy Yulee, Florida Territorial representative to Congress and the first U.S. Senator from Florida when it became a state, member of the Confederate Congress, builder of Florida's first cross-state railroad (Fernandina to Cedar Key).

Attractions

The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking is a 1988 American fantasy-adventure-musical film that was filmed in Fernandina Beach and at soundstages in Jacksonville.[26] The house that stood in for Villa Villekulla, Pippi’s home, is known locally as Captain Bell's House and is located on Estrada Street in the Old Town area directly across from the Fernandina Plaza (parade ground for the Spanish fort) and overlooking the Amelia River.[27]

The Isle of Eight Flags Shrimp Festival occurs during the first weekend in May. Events and activities of the festival include vendors with seafood, arts, crafts, collectibles and antiques, live music, the Miss Shrimp Festival pageant, a fireworks display and a parade.[28]

Historic places

- Original Town of Fernandina Historic Site

- Fairbanks House

- Historic Nassau County Courthouse

- United States Post Office, Custom House, and Courthouse (Fernandina, Florida, 1912)

- Fort Clinch State Park

- See National Register of Historic Places listings in Nassau County, Florida

References

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "The Isle of 8 Flags". www.fbfl.us.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "Fernandina Plaza Historic State Park" (PDF). State of Florida Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks. March 10, 2004. p. 11. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ Spencer Tucker (21 November 2012). Almanac of American Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-59884-530-3.

- ↑ Anthony W. Parker (1 July 2010). Scottish Highlanders in Colonial Georgia: The Recruitment, Emigration, and Settlement at Darien, 1735-1748. University of Georgia Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8203-2718-1.

- ↑ William Bartram (1998). The Travels of William Bartram. University of Georgia Press. pp. 349–350. ISBN 978-0-8203-2027-4.

- ↑ Bland and Associates. "Appendix A: Historic Context and References". Historic Properties Resurvey, City of Fernandina Beach, Nassau County, FL. pp. 7–8.

- 1 2 Louise Biles Hill (1941). "George J. F. Clarke, 1774-1836". Florida Historical Quarterly. 21 (3 ed.). Florida Historical Society. p. 214. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ↑ Howard Jones (2009). Crucible of Power: A history of American foreign relations to 1913. Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Incorporated. pp. 108–112. ISBN 978-0-7425-6534-0. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ Judith Ann Bense (1999). Archaeology of Colonial Pensacola. University Press of Florida. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8130-1661-0.

- ↑ Albert W. Haarmann (October 1960). "The Spanish Conquest of British West Florida, 1779-1781". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 2. 39. Florida Historical Society. p. 108.

- ↑ William C. Davis (20 April 2011). The Rogue Republic: How Would-Be Patriots Waged the Shortest Revolution in American History. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 6. ISBN 0-547-54915-6.

- ↑ University of Southwestern Louisiana. Center for Louisiana Studies (August 1996). The Spanish presence in Louisiana, 1763-1803. Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana. p. 318.

- ↑ Cusick, James G. (2007). The other war of 1812 : the Patriot War and the American invasion of Spanish East Florida. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0820329215.

- 1 2 "Another View of Gregor MacGregor" in Amelia Now On Line, Winter 2001.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Station Name: FL FERNANDINA BEACH". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau. "Fernandina Beach (city), Florida". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Government. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau. "2010 Demographic Profile Data". Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. U.S. Government. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ↑ Berger, Joseph. "Raymond A. Brown, Civil Rights Lawyer, Dies at 94", The New York Times, October 11, 2009. Accessed October 12, 2009.

- ↑ James P. Goss (2000). Pop Culture Florida. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-56164-199-4.

- ↑ http://ameliaislandliving.com/fernandinabeach/2015/11/along-the-river-old-town-fernandina-plaza/

- ↑ "Shrimp festival kicks off in Fernandina Beach". News4Jax. May 3, 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

External links

- City of Fernandina Beach

- Fernandina Beach News-Leader, full text with full page images, freely available in the Florida Digital Newspaper Library

- Fernandina Express, 1880s historic newspaper freely available with full text and full page images in the Florida Digital Newspaper Library

- http://www.floridastateparks.org/fortclinch/default.cfm, the State's official web site for Fort Clinch